Allister Heath in The Telegraph

Imagine that you kept getting it wrong, not just a little, but completely and utterly.

When times were bad you thought they were good, and when they were good you thought they were bad. You argued against successful solutions, and in favour of failed ones. You predicted a rise when in fact a fall materialised; to add insult to injury, you clung to your old ways of thinking, refusing to change apart from in the most trivial of ways. In normal industries you would be finished: your collection of P45s would fill half a drawer, and you would long since have been forced to retrain into somebody of more value to society.

But not in one profession. Yes, dear readers, I’m referring to the systemic, cultural problems of modern, applied macroeconomics, in the public as well as private sectors, where failure continues to be rewarded.

Economists who make all the wrong calls keep their jobs and big paychecks, as long as their faulty views echo the mainstream, received wisdom of the moment. I spent five years studying economics, and I still love the subject. At its best, economics is the answer to myriad problems, the prism through which to view the vast majority of decisions.

But I’m deeply frustrated with some of its practitioners: all those folk who predicted that the third quarter would see very little or negative growth, when in fact the economy grew by a remarkable 0.5pc, the most important statistic of recent times.

For political and psychological reasons, one small and rather unreliable snapshot had become all-important. Had that (preliminary and approximate number) been in negative territory, or close to zero, the outcry would have been deafening and reverberated around the world. The markets would either have slumped or more likely, bounced back, on the assumption that Brexit would be reversed. Yet the opposite happened, and the economy did well (France grew by just 0.2pc during the same time).

Combined with the news that Nissan will be sticking with the UK, it was a great week for Brexit, made all the better by the announcement of Heathrow expansion. Brexit won the referendum, lost the immediate aftermath, won the next few months and has now won again.

Of course, the war continues, and will do so for years. There are huge challenges looming. But this was the week that the economics profession was further discredited. The forecasts were not just completely wrong – my guess is that they were actually downright harmful, shaving growth in areas where elites that are most likely to be swayed by economists decisions.

Economists have form: most backed the euro, failed to see the financial crisis coming, missed the dot.com bubble and the Asian crisis, loved the European Exchange Rate Mechanism and never understood the Thatcherite revolution.

Previous generations failed just as badly: the vast majority loved Keynesian economics during the 1970s, read and recommended a textbook that thought that the USSR would eventually overtake America, backed corporatism, failed to predict the 1929 crash and provided all of the wrong answers in the 1930s.

One problem is groupthink, another is the inability to be objective. But the biggest problem is a faulty paradigm: a fundamental flaw at the heart of the models and assumptions of the economic mainstream, aided and abated by an academic establishment which excludes dissenters from its journals and top faculties.

So if economists want to be useful again, they should do two things.

First, we need a proper Parliamentary inquiry into the failures of the Treasury model and official forecasting before and after Brexit. There is an argument for this to be extended to the Bank of England and even to the private sector. Economists need to cooperate, if even anonymously: are some under pressure to toe various lines? If not, what is the real reason for such a succession of flawed consensuses?

Second, the real threat to the economy is absurd decisions such as the ruling that Uber drivers should be treated like employees (on the basis that the US firm exerts too much control and direction over drivers, even though they are free to choose their hours and commitment).

If not reversed, this judicial activism will destroy jobs and push up prices; it is a shame that such a good week ended on such a sour note. The Government may need to legislate to make it clear that Uber and other similar enterprises are platforms, not employers. If economists want to redeem themselves, they should explain why flexible markets are good and why it would be a genuine disaster if we kill off the sharing economy with red tape.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Saturday, 29 October 2016

India and Intolerance - Free that Pigeon

Irfan Hussain in The Dawn

INDIA has a population of over a billion, a thriving economy, a respected voice, a powerful military and an ancient civilisation. Its scientists have put a satellite into orbit around Mars.

So how does it proclaim its position in the world? By detaining a pigeon allegedly carrying a warning note to Prime Minister Modi. And for good measure, it has expelled a Pakistan High Commission staffer, Mahmood Akhtar, for espionage.

According to The Hindu, Akhtar had recruited two Indians to spy for Pakistan. One of them is Maulana Ramzan Khan, a preacher entrusted with the maintenance of a village mosque. The other is Subhash Jangir, the owner of a small grocery. So clearly no James Bond, either one of them.

The truth is that despite its rapid progress and its size, India is a deeply insecure country. While my columns critical of Pakistan have been met with praise and approval from Indian readers, I have been flooded with furious emails whenever I have said anything negative about their country.

It is almost as though Pakistani journalists were not permitted to talk about their neighbour. And not just Pakistanis: a few years ago, I met the Economist correspondent based in New Delhi who was visiting Lahore to cover the general elections.

Half-jokingly, I said to him that it must be a drag to be in Pakistan during the party season in Delhi. He assured me he loved to visit Pakistan because while in India, readers reviled him whenever he wrote a critical piece for his weekly. But when he wrote a negative article about Pakistan, his Pakistani readers immediately agreed with him.

About 15 years ago, I was in New Delhi, and was invited by the Times of India to speak to their editorial staff. In that informal discussion, I pointed out that despite all of Pakistan’s military interventions, a small group of us writing for the mainstream press still opposed core state policies on Afghanistan, Kashmir and the nuclear programme. The Indian media, on the other hand, were almost unanimous in rallying around the national (and nationalistic) agenda.

None of the journalists present challenged my view. However, one editorial writer pointed out that the ownership pattern of the mainstream press meant that businessmen relying on official contacts did not want to rock the boat.

But the reaction I get to negative articles from Indian readers suggests that the problem goes far deeper. Take the case of Arundhati Roy. Here is a hugely talented writer and a gutsy campaigner who has won international fame for her fiction, as well as for her reporting about the most vulnerable and persecuted segments of Indian society.

On the couple of occasions, I have cited her work in my columns, I have been inundated with emails from Indian readers denouncing her, and insisting that I had lost credibility by quoting Roy.

Clearly, her gritty exposure of the excesses committed by Indian security forces as well as by corporate groups against the marginalised has exposed a raw nerve running through the elites and the expanding middle class.

The current ban prohibiting Pakistani movie stars as well as musicians from acting and performing in India provides another example of the chauvinism that has gripped the country. True, this took place against the backdrop of the bloody attack on an army camp in Uri. But are cultural links to be forever hostage to acts of militancy?

To our shame, we retaliated by imposing a similar ban on Indian movies and TV channels. Had our leaders an ounce of common sense, they could have underlined the crassness of the Indian move by continuing with the previous laissez-faire policy. But sadly, common sense is in short supply on both sides of the border.

So why do so many Indians carry such large chips on their shoulders? Obviously, there is much to admire in the country, ranging from the vibrancy of its arts to its colourful traditions and fascinating history and geography. Then why are they so defensive about the occasional criticism? After all, they cannot hope to bask constantly in international adulation.

While I don’t have any empirical research to back me, I suspect that this touchy reaction to adverse comments derives from India’s history of domination by foreigners. Muslim invaders from Afghanistan and Central Asia ruled much of the subcontinent for the first 800 years or so. They were then displaced by the British who proceeded to govern India for the next couple of centuries.

South India, by contrast, remained largely independent of Muslim rule, and its people are much more self-confident as a result. On a visit to the region several years ago, I was repeatedly told that if it hadn’t been yoked to New Delhi, South India would have made far greater progress.

I realise I am sticking my neck out, and expect the usual flood of angry emails. But would the Indian authorities please set the poor captive pigeon free?

INDIA has a population of over a billion, a thriving economy, a respected voice, a powerful military and an ancient civilisation. Its scientists have put a satellite into orbit around Mars.

So how does it proclaim its position in the world? By detaining a pigeon allegedly carrying a warning note to Prime Minister Modi. And for good measure, it has expelled a Pakistan High Commission staffer, Mahmood Akhtar, for espionage.

According to The Hindu, Akhtar had recruited two Indians to spy for Pakistan. One of them is Maulana Ramzan Khan, a preacher entrusted with the maintenance of a village mosque. The other is Subhash Jangir, the owner of a small grocery. So clearly no James Bond, either one of them.

The truth is that despite its rapid progress and its size, India is a deeply insecure country. While my columns critical of Pakistan have been met with praise and approval from Indian readers, I have been flooded with furious emails whenever I have said anything negative about their country.

It is almost as though Pakistani journalists were not permitted to talk about their neighbour. And not just Pakistanis: a few years ago, I met the Economist correspondent based in New Delhi who was visiting Lahore to cover the general elections.

Half-jokingly, I said to him that it must be a drag to be in Pakistan during the party season in Delhi. He assured me he loved to visit Pakistan because while in India, readers reviled him whenever he wrote a critical piece for his weekly. But when he wrote a negative article about Pakistan, his Pakistani readers immediately agreed with him.

About 15 years ago, I was in New Delhi, and was invited by the Times of India to speak to their editorial staff. In that informal discussion, I pointed out that despite all of Pakistan’s military interventions, a small group of us writing for the mainstream press still opposed core state policies on Afghanistan, Kashmir and the nuclear programme. The Indian media, on the other hand, were almost unanimous in rallying around the national (and nationalistic) agenda.

None of the journalists present challenged my view. However, one editorial writer pointed out that the ownership pattern of the mainstream press meant that businessmen relying on official contacts did not want to rock the boat.

But the reaction I get to negative articles from Indian readers suggests that the problem goes far deeper. Take the case of Arundhati Roy. Here is a hugely talented writer and a gutsy campaigner who has won international fame for her fiction, as well as for her reporting about the most vulnerable and persecuted segments of Indian society.

On the couple of occasions, I have cited her work in my columns, I have been inundated with emails from Indian readers denouncing her, and insisting that I had lost credibility by quoting Roy.

Clearly, her gritty exposure of the excesses committed by Indian security forces as well as by corporate groups against the marginalised has exposed a raw nerve running through the elites and the expanding middle class.

The current ban prohibiting Pakistani movie stars as well as musicians from acting and performing in India provides another example of the chauvinism that has gripped the country. True, this took place against the backdrop of the bloody attack on an army camp in Uri. But are cultural links to be forever hostage to acts of militancy?

To our shame, we retaliated by imposing a similar ban on Indian movies and TV channels. Had our leaders an ounce of common sense, they could have underlined the crassness of the Indian move by continuing with the previous laissez-faire policy. But sadly, common sense is in short supply on both sides of the border.

So why do so many Indians carry such large chips on their shoulders? Obviously, there is much to admire in the country, ranging from the vibrancy of its arts to its colourful traditions and fascinating history and geography. Then why are they so defensive about the occasional criticism? After all, they cannot hope to bask constantly in international adulation.

While I don’t have any empirical research to back me, I suspect that this touchy reaction to adverse comments derives from India’s history of domination by foreigners. Muslim invaders from Afghanistan and Central Asia ruled much of the subcontinent for the first 800 years or so. They were then displaced by the British who proceeded to govern India for the next couple of centuries.

South India, by contrast, remained largely independent of Muslim rule, and its people are much more self-confident as a result. On a visit to the region several years ago, I was repeatedly told that if it hadn’t been yoked to New Delhi, South India would have made far greater progress.

I realise I am sticking my neck out, and expect the usual flood of angry emails. But would the Indian authorities please set the poor captive pigeon free?

Uber ruling is a massive boost for a fairer jobs market

Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian

Yaseen Aslam. James Farrar. Remember those two names, because they are giant-killers. This summer the men took on not just one £50bn multinational, but an entire business model. On Friday, they won.

As minicab drivers for Uber, Aslam and Farrar were deemed to be self-employed. The status meant they were denied the most basic rights that other workers take: no minimum wage, no sick pay, no paid holiday. But as an employment tribunal judge heard over several days in July, that classification was both wrong and unfair. And he agreed.

The obvious thing to say about Anthony Snelson’s ruling is that it is huge. It poses an existential threat to Uber in Britain. It will also send shockwaves through a string of companies using the same business model to do everything from delivering takeaways to providing cleaners to couriering court documents.

Most of all, it is a massive boost for all of us who want a fairer jobs market – and a big slap in the face for the government. For most of the past six years, ministers have turned a blind eye to the growth in bogus self-employment, zero-hours contracts and Sports Direct-style agency work. They have preferred instead to celebrate the record employment numbers as proof that austerity is doing the trick. Just before the last election, Nick Clegg claimed: “If you want a glimpse of the sort of worker that will thrive in the new economy, you need look no further than the growing numbers of self-employed people.”

On this subject too, the hapless Lib Dem was wrong. The idea that the swelling army of self-employed Britons are all budding SurAlans and Bransons, swigging lattes and toting MacBooks, is for the birds. Serious labour-market analysts agree that a large number of those now in self-employment are there as a last resort. And many believe a big chunk should not even be classed as self-employed. As with much else in our insecure labour market, firm numbers are hard to come by. But the Citizens Advice Bureaux believe that the reserve army of bogus self-employed may number around half a million.

For some Britons, self-employment doubtless means freedom. But for others, it means the freedom to be exploited, deprived of rights – and to be underpaid. According to recent research from the Resolution Foundation, the typical self employed Brit is now earning less than when John Major was prime minister.

For the likes of Uber, self-employment is hugely profitable. The giant company has 40,000 drivers working for it in Britain – and as long as they are self-employed they are almost cost-free. On that basis, Uber can keep on adding to its fleet of drivers for next to nothing, and thus rack up ever more passengers and squeeze out competitors.

But as the judge found on Friday, Uber drivers are not self-employed at all. They have little of the liberty you might expect, but are instead interviewed, recruited and controlled by the firm. Uber sets their default driving routes. Uber fixes the fares. Uber instructs them on how to do their job and runs a disciplinary procedure. The drivers work for Uber – not the other way round.

As the ruling observes, the company and its highly-paid boosters do their best to cloak this relationship in the language of chummy marketing and hi-tech piety. They use the term “gig economy”, when what they mean is casualised labour. They claim to be “disrupters”, when what they’re really disrupting are our labour laws. And Uber still markets itself like a plucky underdog when it is now worth $62.5bn – more than Tesco and Barclays put together – and numbers among its public affairs and public relations people the former advisers to Ed Balls and Michael Howard. Pretending to be the future, it is really the past: a cab company that relies on its drivers being cheap and available. Except your local cab firm doesn’t have the lobbying muscle or the Westminster contacts.

Uber confirmed that it will appeal against the decision, and you can expect this case to keep the courts busy for a few months. Other businesses that have copied the Uber model will be watching anxiously. And so will their workers.

A few months back, I interviewed a courier called Mags Dewhurst, whose job is biking urgent medical supplies to hospitals around London. Like most other cycle couriers and drivers, she’s also classified as self-employed; she’s also fighting to change her status. Next month she will be battling her company, CitySprint, in court.

Dewhurst has a strong case. She wears a uniform with a logo, clocks in with a controller each morning. And then: “For 50 hours each week, I’m told what to do.” She’s been impatient for the Uber verdict, knowing that it will be of huge symbolic importance for her own case. On Friday afternoon, I texted her: How pleased are you?

Her reply: “On a scale of 1-10? A GAZZILLLLION.”

Yaseen Aslam. James Farrar. Remember those two names, because they are giant-killers. This summer the men took on not just one £50bn multinational, but an entire business model. On Friday, they won.

As minicab drivers for Uber, Aslam and Farrar were deemed to be self-employed. The status meant they were denied the most basic rights that other workers take: no minimum wage, no sick pay, no paid holiday. But as an employment tribunal judge heard over several days in July, that classification was both wrong and unfair. And he agreed.

The obvious thing to say about Anthony Snelson’s ruling is that it is huge. It poses an existential threat to Uber in Britain. It will also send shockwaves through a string of companies using the same business model to do everything from delivering takeaways to providing cleaners to couriering court documents.

Most of all, it is a massive boost for all of us who want a fairer jobs market – and a big slap in the face for the government. For most of the past six years, ministers have turned a blind eye to the growth in bogus self-employment, zero-hours contracts and Sports Direct-style agency work. They have preferred instead to celebrate the record employment numbers as proof that austerity is doing the trick. Just before the last election, Nick Clegg claimed: “If you want a glimpse of the sort of worker that will thrive in the new economy, you need look no further than the growing numbers of self-employed people.”

On this subject too, the hapless Lib Dem was wrong. The idea that the swelling army of self-employed Britons are all budding SurAlans and Bransons, swigging lattes and toting MacBooks, is for the birds. Serious labour-market analysts agree that a large number of those now in self-employment are there as a last resort. And many believe a big chunk should not even be classed as self-employed. As with much else in our insecure labour market, firm numbers are hard to come by. But the Citizens Advice Bureaux believe that the reserve army of bogus self-employed may number around half a million.

For some Britons, self-employment doubtless means freedom. But for others, it means the freedom to be exploited, deprived of rights – and to be underpaid. According to recent research from the Resolution Foundation, the typical self employed Brit is now earning less than when John Major was prime minister.

For the likes of Uber, self-employment is hugely profitable. The giant company has 40,000 drivers working for it in Britain – and as long as they are self-employed they are almost cost-free. On that basis, Uber can keep on adding to its fleet of drivers for next to nothing, and thus rack up ever more passengers and squeeze out competitors.

But as the judge found on Friday, Uber drivers are not self-employed at all. They have little of the liberty you might expect, but are instead interviewed, recruited and controlled by the firm. Uber sets their default driving routes. Uber fixes the fares. Uber instructs them on how to do their job and runs a disciplinary procedure. The drivers work for Uber – not the other way round.

As the ruling observes, the company and its highly-paid boosters do their best to cloak this relationship in the language of chummy marketing and hi-tech piety. They use the term “gig economy”, when what they mean is casualised labour. They claim to be “disrupters”, when what they’re really disrupting are our labour laws. And Uber still markets itself like a plucky underdog when it is now worth $62.5bn – more than Tesco and Barclays put together – and numbers among its public affairs and public relations people the former advisers to Ed Balls and Michael Howard. Pretending to be the future, it is really the past: a cab company that relies on its drivers being cheap and available. Except your local cab firm doesn’t have the lobbying muscle or the Westminster contacts.

Uber confirmed that it will appeal against the decision, and you can expect this case to keep the courts busy for a few months. Other businesses that have copied the Uber model will be watching anxiously. And so will their workers.

A few months back, I interviewed a courier called Mags Dewhurst, whose job is biking urgent medical supplies to hospitals around London. Like most other cycle couriers and drivers, she’s also classified as self-employed; she’s also fighting to change her status. Next month she will be battling her company, CitySprint, in court.

Dewhurst has a strong case. She wears a uniform with a logo, clocks in with a controller each morning. And then: “For 50 hours each week, I’m told what to do.” She’s been impatient for the Uber verdict, knowing that it will be of huge symbolic importance for her own case. On Friday afternoon, I texted her: How pleased are you?

Her reply: “On a scale of 1-10? A GAZZILLLLION.”

Friday, 28 October 2016

Cricket - Be your own role model

Pete Langman in Cricinfo

The Temple of Apollo, where the Oracle of Delphi plied her trade, was renowned for having the maxim "know thyself" carved into its stone. This, along with Polonius' parting words to Laertes in Hamlet, "to thine own self be true", is perhaps the best advice that a cricketer can be given. For cricket, in all of its infinite variety, relies on judgement more than any other skill, and if there's one judgement that is absolutely vital, it is that of the self.

Geoffrey Boycott, for all his faults, knows a thing or two about the game. One of his mantras is "Make your opponent do something they don't want to do." He says this because it's true.

If you're bowling to Alastair Cook, you don't pitch the ball short and wide, or on his hips, you pitch it outside off... and when he's struggling, when his footwork isn't just so, or he's overbalancing, he'll invariably have a nibble. When he's in form, however, his judgement is impeccable. Ignoring practically everything that isn't in his arc, he simply waits for the bad ball and puts it away, and his leave is a thing of frustrating beauty. He's not the most elegant, attractive or technically proficient member of the England set-up, but one look at the numbers show just how effective a cricketer he is. This is because he knows his own game.

In April 1997, an article appeared in the music press arguing that accurate self-assessment was vital for a musician to perform at their best, and described a psychological test that could quantify the gap between a performer's self-belief and his or her actual ability. It was, as the month of publication suggests, a joke, though like all good jokes it was built around close observation and understanding. Two years later, in 1999, two psychologists at Cornell University came to a similar conclusion, noting that low-ability individuals consistently overestimate their skill levels, while the converse is true of high-ability individuals. They called it the Dunning-Kruger effect. I called it the Position of Attitudes.

We've all seen the results of extreme disparity between actual and perceived ability. The batsman who thinks he can hit every ball for six but is always oh-so-unlucky; the bowler who is convinced he's lightning fast and pitches it short and shorter still, but will get the batsman soon. Neither cricketer wins games.

Accurately gauging one's own ability relative to that of the other players on the field (whether they are on your side or not) is a vital part of playing at one's best.

As a wicketkeeper who sometimes keeps above himself, it's a constant battle to find the right place to stand, especially to spinners. Obviously one ought to stand up to spin, but some bowlers are just too quick for me. I leak byes and am unlikely to take many nicks. Standing back even a yard or two may take stumpings out of the equation, but the byes dry up and I pouch the nicks.

We must allow ourselves to play our own game. Yes, we adapt to the situation, and sometimes that means we must take greater risks, but in acknowledging those risks we may still make the best of it

I know my own capabilities, and usually keep within them, but sometimes I give in to pressure and move to where someone else thinks I ought to stand. It rarely goes well. I'm pretty confident I know my keeping self.

When batting, the same is true. If you're aware of your limitations (and accept them), then you reduce the risk of failure. It's when you're tempted to overreach that things go badly. You decide to go for big shots when you're really a nudger and a nurdler.

On tour this summer, I played a vital innings batting at No. 5 (when I was probably the 12th best bat in the team) during which I watched partner after partner try too hard and perish accordingly. I simply waited for the ball to be well within my arc. It worked because I played to my strengths (such as they are) and made the bowlers come to me. Occasionally I simply tee off. This doesn't go so well.

We must allow ourselves to play our own game and not be lured into playing someone else's. No matter what the wicketkeeper says. Yes, we adapt to the situation, and yes, sometimes that means we must take greater risks, but in acknowledging those risks we may still make the best of it. Try to hit the ball too hard, try to bowl it too fast, try too many variations and the percentages plummet. Ask not, as they say, what the ball is going to do to you, but what you can actually do with the ball.

The England Test side has left in its wake many who have struggled to succeed because they have tried to change their natural game. And by this I don't mean adapting to the new arena, fine-tuning technique, or working on shot selection.

Nick Compton, convinced he needed to impress, tried to change his natural game and was caught hooking. Alex Hales struggled as an opener because he couldn't decide who to be: had he played freely he may still have failed, but that's okay. Yes, James Vince, Gary Ballance and a few others have arguably failed to make their game work at Test level, but they were honest with themselves in the process. Fail on your own terms, not somebody else's.

When Ben Duckett and Haseeb Hameed opened together in the warm-up game in Bangladesh, they were in direct competition for the vacant opening berth. Both played their own game, neither trying to impress. The result? They both impressed. This can only be good for English cricket.

We should aim to do the same, learn from Duckett and Hameed and be our own role models.

Geoffrey Boycott, for all his faults, knows a thing or two about the game. One of his mantras is "Make your opponent do something they don't want to do." He says this because it's true.

If you're bowling to Alastair Cook, you don't pitch the ball short and wide, or on his hips, you pitch it outside off... and when he's struggling, when his footwork isn't just so, or he's overbalancing, he'll invariably have a nibble. When he's in form, however, his judgement is impeccable. Ignoring practically everything that isn't in his arc, he simply waits for the bad ball and puts it away, and his leave is a thing of frustrating beauty. He's not the most elegant, attractive or technically proficient member of the England set-up, but one look at the numbers show just how effective a cricketer he is. This is because he knows his own game.

In April 1997, an article appeared in the music press arguing that accurate self-assessment was vital for a musician to perform at their best, and described a psychological test that could quantify the gap between a performer's self-belief and his or her actual ability. It was, as the month of publication suggests, a joke, though like all good jokes it was built around close observation and understanding. Two years later, in 1999, two psychologists at Cornell University came to a similar conclusion, noting that low-ability individuals consistently overestimate their skill levels, while the converse is true of high-ability individuals. They called it the Dunning-Kruger effect. I called it the Position of Attitudes.

We've all seen the results of extreme disparity between actual and perceived ability. The batsman who thinks he can hit every ball for six but is always oh-so-unlucky; the bowler who is convinced he's lightning fast and pitches it short and shorter still, but will get the batsman soon. Neither cricketer wins games.

Accurately gauging one's own ability relative to that of the other players on the field (whether they are on your side or not) is a vital part of playing at one's best.

As a wicketkeeper who sometimes keeps above himself, it's a constant battle to find the right place to stand, especially to spinners. Obviously one ought to stand up to spin, but some bowlers are just too quick for me. I leak byes and am unlikely to take many nicks. Standing back even a yard or two may take stumpings out of the equation, but the byes dry up and I pouch the nicks.

We must allow ourselves to play our own game. Yes, we adapt to the situation, and sometimes that means we must take greater risks, but in acknowledging those risks we may still make the best of it

I know my own capabilities, and usually keep within them, but sometimes I give in to pressure and move to where someone else thinks I ought to stand. It rarely goes well. I'm pretty confident I know my keeping self.

When batting, the same is true. If you're aware of your limitations (and accept them), then you reduce the risk of failure. It's when you're tempted to overreach that things go badly. You decide to go for big shots when you're really a nudger and a nurdler.

On tour this summer, I played a vital innings batting at No. 5 (when I was probably the 12th best bat in the team) during which I watched partner after partner try too hard and perish accordingly. I simply waited for the ball to be well within my arc. It worked because I played to my strengths (such as they are) and made the bowlers come to me. Occasionally I simply tee off. This doesn't go so well.

We must allow ourselves to play our own game and not be lured into playing someone else's. No matter what the wicketkeeper says. Yes, we adapt to the situation, and yes, sometimes that means we must take greater risks, but in acknowledging those risks we may still make the best of it. Try to hit the ball too hard, try to bowl it too fast, try too many variations and the percentages plummet. Ask not, as they say, what the ball is going to do to you, but what you can actually do with the ball.

The England Test side has left in its wake many who have struggled to succeed because they have tried to change their natural game. And by this I don't mean adapting to the new arena, fine-tuning technique, or working on shot selection.

Nick Compton, convinced he needed to impress, tried to change his natural game and was caught hooking. Alex Hales struggled as an opener because he couldn't decide who to be: had he played freely he may still have failed, but that's okay. Yes, James Vince, Gary Ballance and a few others have arguably failed to make their game work at Test level, but they were honest with themselves in the process. Fail on your own terms, not somebody else's.

When Ben Duckett and Haseeb Hameed opened together in the warm-up game in Bangladesh, they were in direct competition for the vacant opening berth. Both played their own game, neither trying to impress. The result? They both impressed. This can only be good for English cricket.

We should aim to do the same, learn from Duckett and Hameed and be our own role models.

Imran Khan and Insaaf or Justice

Najam Sethi in The Friday Times

There is no justice or “insaf” in Pakistan. That is why citizens clutched desperately at the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf. There is rampant corruption and voracious greed in Pakistan. That is why citizens lent their shoulder to fashioning the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party. Every political leader in Pakistan is corrupt and incompetent and uncaring. That is why citizens put their hope and faith in Imran Khan, who was educated at Aitchison College in Lahore and Oxford University UK; who is a cricketing hero under whose captainship Pakistan won the World Cup in 1992; whose Shaukat Khanum Hospital is a beacon of light for the wretched and hopeless. Yet, the sound and fury of Imran Khan and the PTI has not signified anything that can remotely signal a serious or even sincere attempt to grapple purposefully with these real issues. The PTI is a one-man party whose leader is mercurial, autocratic, fickle, ill informed, misguided. There is no Insaf or internal democracy in it. There are corrupt lotas in it. The financial misdemeanors of its leaders, including misappropriation and misuse of party funds donated by well-wishers and supporters, cannot be brushed under the carpet. Worse, Khan’s double standards on morality are outrageous.

There is no justice or “insaf” in Pakistan. All hopes were pinned on the Lawyers Movement to restore an independent and qualified judiciary led by CJP Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhry to fill this vacuum. Yet, nearly a decade after it was launched and after eight years of stewardship by Mr Chaudhry, that pious hope has all but faded. Mr Chaudhry’s populist suo motu notices and summons made headlines but quickly evaporated thereafter. Many of his judicial appointments politicized the judiciary and made it more controversial and less transparent or competent. In the end, the ex-chief justice has been reduced to squabbling with his benefactor Nawaz Sharif over the mundane spoils of retirement – a bullet proof vehicle, to boot – as he squats rather pathetically over a one man political party with an eminently forgettable name.

It is therefore not surprising that the cry for Insaf or Justice is still ringing loud and true. What is ironic, however, is that it is Imran Khan’s PTI that is knocking on the door of the Supreme Court, after having trashed state institutions like ECP, NAB, FBR, FIA, etc, as “worthless” and “corrupt”. It is Imran Khan’s PTI that first demanded the formation of a SC judicial commission on election rigging, then rubbished its findings when these didn’t suit it, and is now praying before the same SC to investigate the corrupt practices of Nawaz Sharif though the very state institutions like NAB, FBR and FIA that he has earlier denounced.

The SC is clearly in an unenviable position. On the one hand, it is trying to undo some of the consequences of an errant ex-chief justice, some of whose judicial appointees are facing inquiries in the Supreme Judicial Council or whose judgments have been blithely overturned (eg illegal appointments in the Islamabad High Court by an ex-chief justice who has had to resign) etc. On the other hand, it is trying to clean up the arch anti-corruption watchdog NAB that is accused of serious malpractices relating to the discretionary powers of the Chairman NAB (to adjudicate cases involving Plea Bargains or Voluntary Returns of Corruption Monies). This, while it claims to be the leading edge of the investigations demanded by Imran Khan against Nawaz Sharif. The irony is that the very chief justice of Pakistan who rejected Nawaz Sharif’s request six months ago to conduct a corruption inquiry because he felt that the inquiry law was inappropriate for the occasion is now entertaining the same petitions from the same protagonists on the same issues, and there is no discussion yet of the law or Terms Of Reference under which such an inquiry is proposed to be held.

The latest twist in this saga of Insaf-No Insaf again originates from the indefatigable Imran Khan and relates inevitably to the Sharifs. Imran has just accused Shahbaz Sharif of billions in corruption commissions though a front businessman. The self-righteous SS has retaliated by – you guessed it! – suing and bankrupting him in court. Indeed, he insists on fast tracking the court proceedings in order to get Insaf and clear his good name. But here’s the rub. The last recorded libel case that actually came to a conclusion took ten years and ended with a whimper of an apology from the wretched accuser. It is also highly doubtful that there is any judge in the country who will have the courage to deliver Insaf to anyone genuinely wronged by Imran Khan. Such is the populist clout and charisma wielded by the foremost advocate of Insaf against the very precepts of Insaf!

It is all looking rather hopeless. It seems that no state institution or political party or leader is up to the task of provisioning Insaf transparently across the board.

There is no justice or “insaf” in Pakistan. That is why citizens clutched desperately at the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf. There is rampant corruption and voracious greed in Pakistan. That is why citizens lent their shoulder to fashioning the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party. Every political leader in Pakistan is corrupt and incompetent and uncaring. That is why citizens put their hope and faith in Imran Khan, who was educated at Aitchison College in Lahore and Oxford University UK; who is a cricketing hero under whose captainship Pakistan won the World Cup in 1992; whose Shaukat Khanum Hospital is a beacon of light for the wretched and hopeless. Yet, the sound and fury of Imran Khan and the PTI has not signified anything that can remotely signal a serious or even sincere attempt to grapple purposefully with these real issues. The PTI is a one-man party whose leader is mercurial, autocratic, fickle, ill informed, misguided. There is no Insaf or internal democracy in it. There are corrupt lotas in it. The financial misdemeanors of its leaders, including misappropriation and misuse of party funds donated by well-wishers and supporters, cannot be brushed under the carpet. Worse, Khan’s double standards on morality are outrageous.

There is no justice or “insaf” in Pakistan. All hopes were pinned on the Lawyers Movement to restore an independent and qualified judiciary led by CJP Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhry to fill this vacuum. Yet, nearly a decade after it was launched and after eight years of stewardship by Mr Chaudhry, that pious hope has all but faded. Mr Chaudhry’s populist suo motu notices and summons made headlines but quickly evaporated thereafter. Many of his judicial appointments politicized the judiciary and made it more controversial and less transparent or competent. In the end, the ex-chief justice has been reduced to squabbling with his benefactor Nawaz Sharif over the mundane spoils of retirement – a bullet proof vehicle, to boot – as he squats rather pathetically over a one man political party with an eminently forgettable name.

It is therefore not surprising that the cry for Insaf or Justice is still ringing loud and true. What is ironic, however, is that it is Imran Khan’s PTI that is knocking on the door of the Supreme Court, after having trashed state institutions like ECP, NAB, FBR, FIA, etc, as “worthless” and “corrupt”. It is Imran Khan’s PTI that first demanded the formation of a SC judicial commission on election rigging, then rubbished its findings when these didn’t suit it, and is now praying before the same SC to investigate the corrupt practices of Nawaz Sharif though the very state institutions like NAB, FBR and FIA that he has earlier denounced.

The SC is clearly in an unenviable position. On the one hand, it is trying to undo some of the consequences of an errant ex-chief justice, some of whose judicial appointees are facing inquiries in the Supreme Judicial Council or whose judgments have been blithely overturned (eg illegal appointments in the Islamabad High Court by an ex-chief justice who has had to resign) etc. On the other hand, it is trying to clean up the arch anti-corruption watchdog NAB that is accused of serious malpractices relating to the discretionary powers of the Chairman NAB (to adjudicate cases involving Plea Bargains or Voluntary Returns of Corruption Monies). This, while it claims to be the leading edge of the investigations demanded by Imran Khan against Nawaz Sharif. The irony is that the very chief justice of Pakistan who rejected Nawaz Sharif’s request six months ago to conduct a corruption inquiry because he felt that the inquiry law was inappropriate for the occasion is now entertaining the same petitions from the same protagonists on the same issues, and there is no discussion yet of the law or Terms Of Reference under which such an inquiry is proposed to be held.

The latest twist in this saga of Insaf-No Insaf again originates from the indefatigable Imran Khan and relates inevitably to the Sharifs. Imran has just accused Shahbaz Sharif of billions in corruption commissions though a front businessman. The self-righteous SS has retaliated by – you guessed it! – suing and bankrupting him in court. Indeed, he insists on fast tracking the court proceedings in order to get Insaf and clear his good name. But here’s the rub. The last recorded libel case that actually came to a conclusion took ten years and ended with a whimper of an apology from the wretched accuser. It is also highly doubtful that there is any judge in the country who will have the courage to deliver Insaf to anyone genuinely wronged by Imran Khan. Such is the populist clout and charisma wielded by the foremost advocate of Insaf against the very precepts of Insaf!

It is all looking rather hopeless. It seems that no state institution or political party or leader is up to the task of provisioning Insaf transparently across the board.

Cricket: Are we living through a new era of spin?

Warne and Murali's big turn has given way to something more subtle.

Jon Hotten in Cricinfo

The life of the impoverished writer has an occasional upside, and one of those came along a couple of weeks ago at the Guildford Book Festival, where I did an event with Tom Collomosse, cricket correspondent for the Evening Standard and Mark Nicholas, the former Hampshire captain turned commentator. Nicholas told a story about facing Derek Underwood on an uncovered pitch. It was early in his career, which began at Hampshire in 1978. They were playing Kent in a three-day game and when the rain came down, the captains got together and negotiated a deal: Hampshire would chase 160 on the last afternoon to win.

Paul Terry and Gordon Greenidge went in. Greenidge took six from the first over. Underwood opened at the other end and Terry got through it by playing from as deep in his crease as he could get. Greenidge took another six runs from the next at his end. Underwood came in again, having had six deliveries to work out the pitch. By the time Nicholas had been in and out shortly afterwards, Hampshire were 12 for 4.

"Derek didn't really bowl spin on wet pitches," he explained. "What he did was hold it down the seam and cut the ball. When you were at the non-striker's end, you could hear it" - he made a whirring sound - "it was an amazing thing."

Nicholas described the nearly impossible task of trying to bat against a ball that reared up from almost medium pace with fielders surrounding you and the immaculate Alan Knott breathing down your neck from behind the stumps. Hampshire lost, of course.

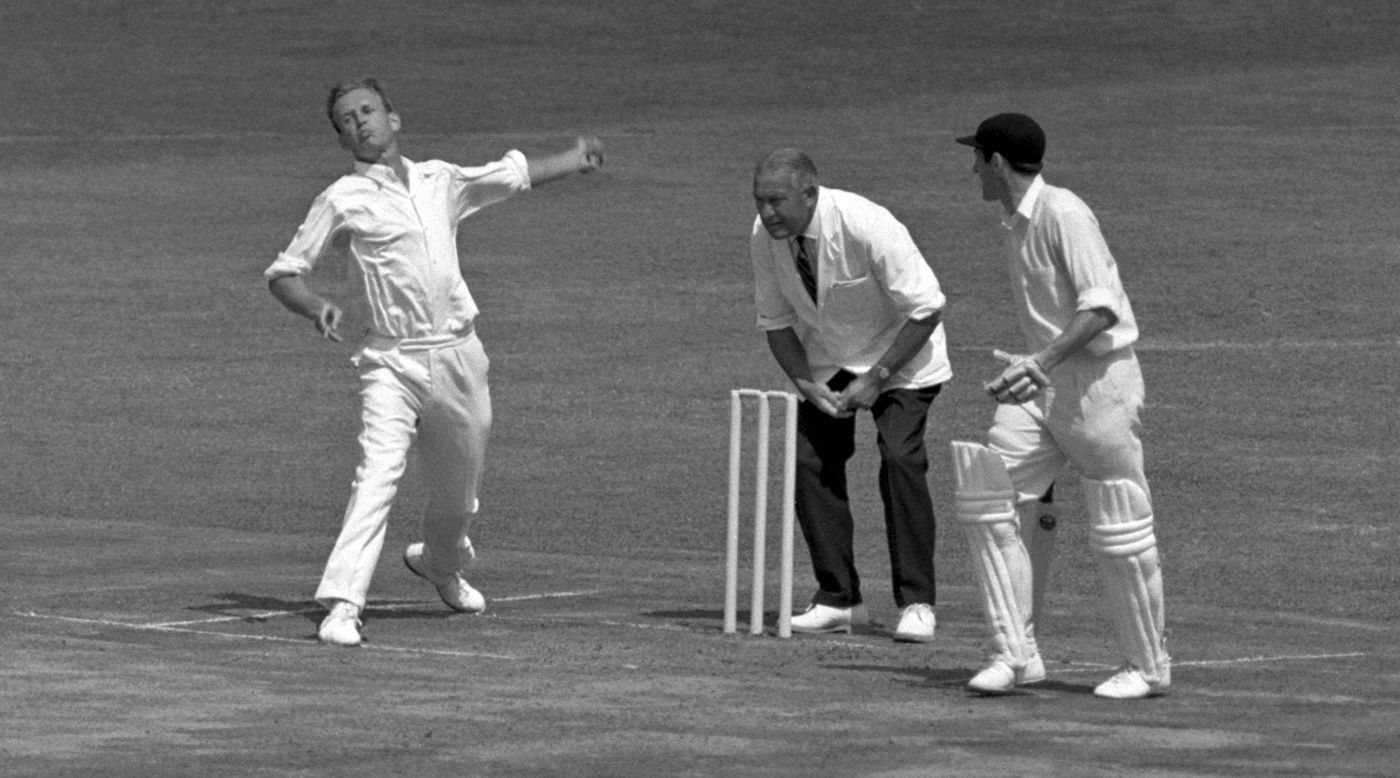

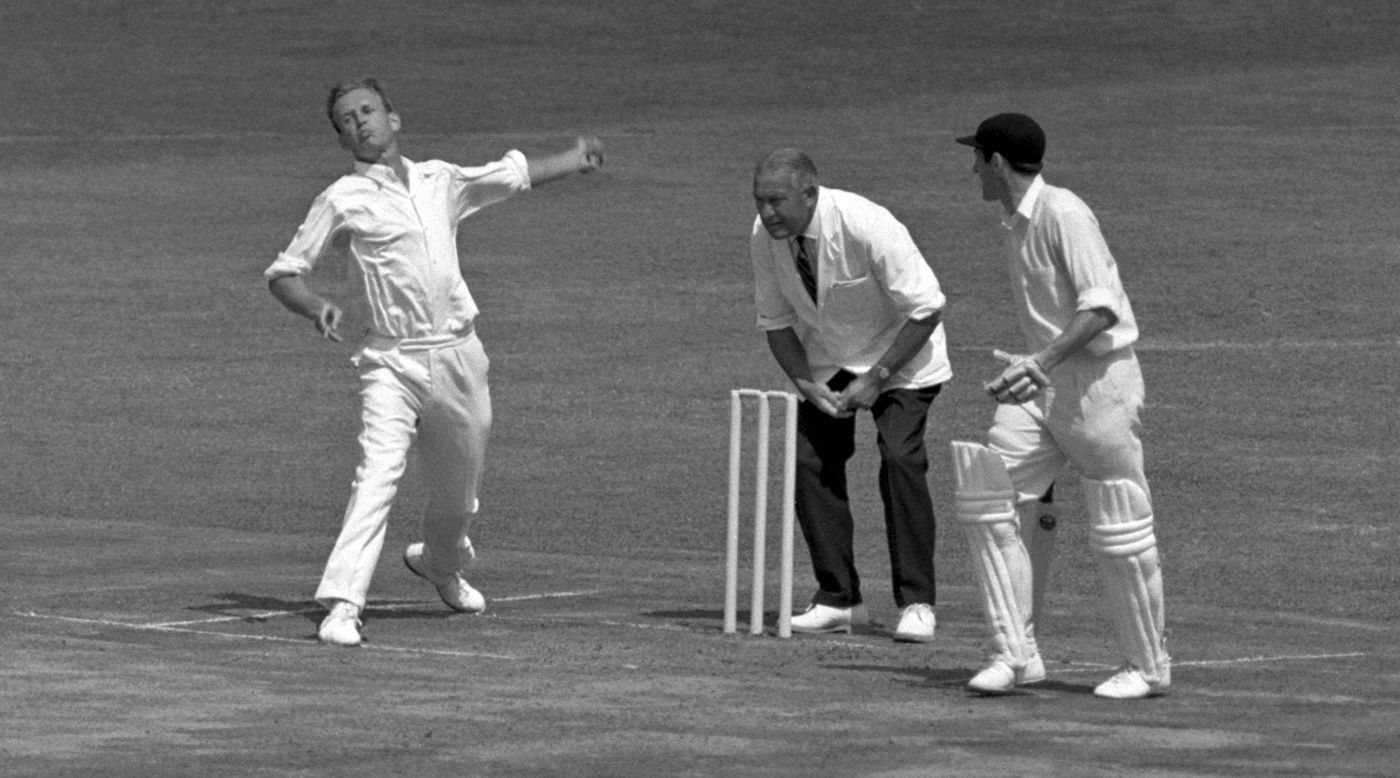

"Deadly" Derek and uncovered pitches are a part of history now, but those who can recall his flat-footed, curving run and liquid movement through the crease saw a bowler who was much more than just a specialist on drying wickets. Whatever the weather, whatever the day, he had the ball for it: 2465 first-class wickets at 20.28 tell his story.

Underwood had a thousand of those wickets by the age of 25 and retired in 1987 at 42. The game, and spin bowling, have changed irrevocably since, yet the spooky art is still shining, and perhaps about to enter a new golden age.

R Ashwin stands at the top of the Test bowling rankings, New Zealand the latest to fall to his strange magic. His buddy Ravindra Jadeja knocks them down at the other end. Bangladesh unleashed the 18-year-old Mehedi Hasan on England, and he had a five-bag on day one. Even England - brace yourselves for this - played three spinners in that game, and may well do so throughout the first part of the winter. Far from killing spin bowling, as it was supposed to do, the new way of batting has encouraged a new style of response.

On wet wickets, Derek Underwood would bowl cutters © PA Photos

On wet wickets, Derek Underwood would bowl cutters © PA Photos

To chart an evolution is fascinating. It is not so long since Shane Warne and Muttiah Muralitharan and Anil Kumble slipped from the game, Warne having reasserted legspin, Murali reinventing offspin. The future looked as though it may be big; huge freaky turn of the kind that pair specialised in. Instead, it has become something more subtle: the notion of beating the bat narrowly on both edges.

These are broad brush strokes of course, and evolution doesn't come in a straight line. It's deeply intriguing though that T20 cricket has played such a role. Through Ashwin, who emerged there, and Jadeja and Sunil Narine and others, it raised the value of cleverness, of invention. Big bats were sometimes defeated by small or no turn. The slow ball was harder to hit. As the techniques bled into Test cricket, where wickets deteriorate and change and the psychology of batting switches, they have grown in value.

We're undoubtedly living through an era in which batting has been revolutionised, undergoing its greatest change in a century. It's the nature of the game that bowling should come up with an answer, and maybe we're starting to see its first iterations. As Jarrod Kimber pointed out in his piece about the inquest into the death of Phillip Hughes, there are more very fast bowlers around now than for generations. Spin bowling is making its move too. And just as the small increments in speed increase in value the higher they go - ask any batsman about the difference between 87mph and 90mph, and then 90mph and 93 or 94mph - the small changes that, for example, Ashwin is producing have their dividend too.

Underwood once described bowling, tongue no doubt in cheek, as, "a low-mentality occupation". His variation was as simple as an arm ball, and yet in the pre-DRS age, it brought him many lbw decisions. Now the subtle changes in the spooky art are wrecking a new and welcome kind of havoc of which Deadly will surely approve. Should we call it the era of small spin?

Jon Hotten in Cricinfo

The life of the impoverished writer has an occasional upside, and one of those came along a couple of weeks ago at the Guildford Book Festival, where I did an event with Tom Collomosse, cricket correspondent for the Evening Standard and Mark Nicholas, the former Hampshire captain turned commentator. Nicholas told a story about facing Derek Underwood on an uncovered pitch. It was early in his career, which began at Hampshire in 1978. They were playing Kent in a three-day game and when the rain came down, the captains got together and negotiated a deal: Hampshire would chase 160 on the last afternoon to win.

----Also read

----

Paul Terry and Gordon Greenidge went in. Greenidge took six from the first over. Underwood opened at the other end and Terry got through it by playing from as deep in his crease as he could get. Greenidge took another six runs from the next at his end. Underwood came in again, having had six deliveries to work out the pitch. By the time Nicholas had been in and out shortly afterwards, Hampshire were 12 for 4.

"Derek didn't really bowl spin on wet pitches," he explained. "What he did was hold it down the seam and cut the ball. When you were at the non-striker's end, you could hear it" - he made a whirring sound - "it was an amazing thing."

Nicholas described the nearly impossible task of trying to bat against a ball that reared up from almost medium pace with fielders surrounding you and the immaculate Alan Knott breathing down your neck from behind the stumps. Hampshire lost, of course.

"Deadly" Derek and uncovered pitches are a part of history now, but those who can recall his flat-footed, curving run and liquid movement through the crease saw a bowler who was much more than just a specialist on drying wickets. Whatever the weather, whatever the day, he had the ball for it: 2465 first-class wickets at 20.28 tell his story.

Underwood had a thousand of those wickets by the age of 25 and retired in 1987 at 42. The game, and spin bowling, have changed irrevocably since, yet the spooky art is still shining, and perhaps about to enter a new golden age.

R Ashwin stands at the top of the Test bowling rankings, New Zealand the latest to fall to his strange magic. His buddy Ravindra Jadeja knocks them down at the other end. Bangladesh unleashed the 18-year-old Mehedi Hasan on England, and he had a five-bag on day one. Even England - brace yourselves for this - played three spinners in that game, and may well do so throughout the first part of the winter. Far from killing spin bowling, as it was supposed to do, the new way of batting has encouraged a new style of response.

On wet wickets, Derek Underwood would bowl cutters © PA Photos

On wet wickets, Derek Underwood would bowl cutters © PA PhotosTo chart an evolution is fascinating. It is not so long since Shane Warne and Muttiah Muralitharan and Anil Kumble slipped from the game, Warne having reasserted legspin, Murali reinventing offspin. The future looked as though it may be big; huge freaky turn of the kind that pair specialised in. Instead, it has become something more subtle: the notion of beating the bat narrowly on both edges.

These are broad brush strokes of course, and evolution doesn't come in a straight line. It's deeply intriguing though that T20 cricket has played such a role. Through Ashwin, who emerged there, and Jadeja and Sunil Narine and others, it raised the value of cleverness, of invention. Big bats were sometimes defeated by small or no turn. The slow ball was harder to hit. As the techniques bled into Test cricket, where wickets deteriorate and change and the psychology of batting switches, they have grown in value.

We're undoubtedly living through an era in which batting has been revolutionised, undergoing its greatest change in a century. It's the nature of the game that bowling should come up with an answer, and maybe we're starting to see its first iterations. As Jarrod Kimber pointed out in his piece about the inquest into the death of Phillip Hughes, there are more very fast bowlers around now than for generations. Spin bowling is making its move too. And just as the small increments in speed increase in value the higher they go - ask any batsman about the difference between 87mph and 90mph, and then 90mph and 93 or 94mph - the small changes that, for example, Ashwin is producing have their dividend too.

Underwood once described bowling, tongue no doubt in cheek, as, "a low-mentality occupation". His variation was as simple as an arm ball, and yet in the pre-DRS age, it brought him many lbw decisions. Now the subtle changes in the spooky art are wrecking a new and welcome kind of havoc of which Deadly will surely approve. Should we call it the era of small spin?

Thursday, 27 October 2016

Assumptions of Modern Science

by Girish Menon

Modern science is founded on the belief in the Genesis, that nature was created by a law-giving God and so we must be governed by "laws of nature".

Equally important was the belief that human beings are made in the image of God and, as a consequence, can understand these "laws of nature".

What do scientists have to say to that?

I say all scientists are therefore Judeo-Christian in their beliefs.

Modern science is founded on the belief in the Genesis, that nature was created by a law-giving God and so we must be governed by "laws of nature".

Equally important was the belief that human beings are made in the image of God and, as a consequence, can understand these "laws of nature".

What do scientists have to say to that?

I say all scientists are therefore Judeo-Christian in their beliefs.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)