Just over 40 years ago, I wrote a play called Knuckle which tried out for two weeks at the Oxford Playhouse, before going on to open in the West End. It was my fourth full-length play, and one that suffered an extremely difficult birth. I was 26. If only I had known it, its reception was to have a decisive and lasting effect on my life. Knuckle was produced at a time of bitter and fundamental industrial disputes, so the hotel I stayed in along from the theatre was subject to blackouts. It was February and it was freezing cold, and there were evenings when the hotel was lit only by candles placed on the stairs and in my room.

Edward Heath, a Conservative prime minister, was about to announce a markedly unwise election based around the question of “Who runs Britain?” He was tired, he said, of the trade unions having too much power and he wanted to settle the arguments between government and workers once and for all. At the end of February 1974, the electorate gave him a dusty answer – it is always said to be a mistake to go to the people with a question they expect you to answer for yourself – but Heath hung on for a few undignified days in Downing Street, trying to cobble together a coalition, before gracelessly accepting the inevitable. Harold Wilson, the victor, quickly settled with the miners, and the lights came back on again.

The past is comparatively safe, next to the present, because we know how at least one of them turns out. Or do we? One of my purposes last year in publishing a memoir, The Blue Touch Paper, was to reclaim the 1970s from the image that politicians of one fierce bent have successfully imposed with the help of largely compliant historians. The now-familiar version of our island story is that we all spent the 1970s in industrial chaos, with successive governments failing to confront the overbearing unions, until Margaret Thatcher arrived and set about deregulating markets, privatising public assets and generally encouraging citizens to work only for ourselves and our own self-interest. This, we have been continually told over three decades of sustained propaganda, was wholly to the good. The country we now live in with all its crazy excesses of inequality and flagrant immorality in the workplace – bosses in large firms averaging 160 times the salaries of their worst-off employees – is said to be far superior to how it was in the days when labour still held management in some kind of check.

History belongs to the victors. Conservatives in Britain now command not just the economy but the narrative as well, and three recent Labour governments have done little to challenge it. But it is not the case that everything was in chaos until 1979, since when everything has been bliss. The 1970s were disputatious times, times of profound and often bitter argument. Living through them was not easy, and a lot of us suffered wounds that took years to heal. But the political discussions we were having – in particular about how the wishes of working-class employees could be more creatively taken into account – were about important things, things that, disastrously, present-day politicians disdain to address. The shocking rancour of the 1970s now looks like a symptom of their vitality. Today’s quiescence seems more like a phenomenon of resignation than of contentment.

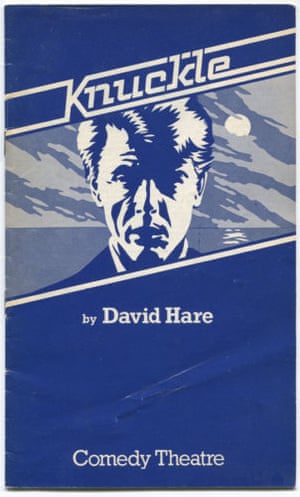

David Hare’s play Knuckle in 1974 featured a father and son who represented two contrasting strands in conservatism. Photograph: Comedy Theatre

Knuckle was a youthful pastiche of an American thriller, relocating the myth of the hard-boiled private eye incongruously into the home counties. Curly Delafield, a young arms dealer, returns to Guildford in order to try and find his sister Sarah who has disappeared. But in the process he finds himself freshly infuriated by the civilised hypocrisy of his father Patrick Delafield, a stockbroker of the old school. In the play father and son represent two contrasting strands in conservatism. Patrick, the father, is cultured, quiet and responsible. Curly, the son, is aggressive, buccaneering and loud. One of them sees the creation of wealth as a mature duty to be discharged for the benefit of the whole community, with the aim of perpetuating a way of life that has its own distinctive character and tradition. But the other character, based on various criminal or near-criminal racketeers who were beginning to play a more prominent role in British finance in the 1970s, sees such thinking as outdated. Curly’s own preference is to make as much money as he can in as many fields as he can and then to get out fast.

The first thing to notice about my play is that it was written in 1973. Margaret Thatcher was not elected until six years later. So whatever the impact of her arrival at the end of decade, it would be wrong to say that she brought anything very new to a Tory schism that had been latent for years. Surely, she showed power and conviction in advancing the cause of the Curly Delafield version of capitalism – no good Samaritan could operate, she once argued, unless the Samaritan were filthy rich in the first place. How else to explain the fact that the very split that she formally confronted in the different mindsets within her government – she named the two opposing sides “wets” and “drys” – was explored in my work at the Oxford Playhouse more than five years before? In 1951, resolving never to vote for them again, the novelist Evelyn Waugh had complained that the Conservative party in his lifetime “had never put the clock back a single second”. But the administrations that Thatcher first led and then inspired have never shown interest in conserving anything at all. The giveaway, for once, has not been in the name.

You may say that the party aims, like all such parties, to keep the well off well off. That, never forget, is any rightwing grouping’s conservative mission, which will offer a blindingly simple explanation for the larger part of its behaviour. And for obvious reasons, the money party in this particular culture has also aimed to perpetuate the narcotic influence of the monarchy. But with these two exceptions, it is hard to think of any area of public activity – education, justice, defence, health, culture – which any of the last seven Conservative governments have been interested in protecting, let alone conserving. On the contrary, they have preferred a state of near‑Maoist revolution, complaining that, in an extraordinary coincidence, almost every aspect of British life except retail and finance is incompetently organised. Who could have imagined it? And after all those dominant Conservative governments! In this belief, they have launched waves of attacks against teachers, doctors, nurses, policemen and women, soldiers, social workers, civil servants, local councillors, firefighters, broadcasters and transport workers – all of whom they openly scorn for the mortal sin of not being financiers or entrepreneurs.

For a party that is meant to like people, and to believe in enabling them, the modern Conservative party, once inclusive, has had, to say the least, a funny way of showing it. From every government department we regularly expect sallies against the very people who toil in the sector that the minister is supposed to lead. If there were at this moment a Ministry of Fruit Picking, you can be damn sure that the only way an ambitious Tory minister could advance his career would be by launching a blistering attack on the feckless indolence and inefficiency of fruit pickers.

It would be dishonest, however, to pretend any kind of nostalgia for the earlier, smugger form of conservatism. It is commonly said that leaders such as Harold Macmillan had either fought in the trenches or known men at first hand in their industrial constituencies and so gained a respect for working-class life, which the 21st-century leadership, with its upmarket aura of fine wine and evenings spent manspreading with sofa-sprawled box sets, conspicuously lacks. But this is to ignore the repellent layer of snobbery on which such sympathy relied. Even if, like me, you find the modern snobbery of a Notting Hill Cameron, who would rather be seen to be cool than to be caught out being compassionate, even more disgusting than the old-fashioned kind – because it is so much more cynical and calculated – nevertheless there was in the blimpish tone of the old conservatism an air of right-to-rule that saw the country as its plaything and government as its entitlement. Winston Churchill’s outrage at being booted out at the end of the second world war and the ruling class’s linking of the words “inexplicable” and “ingratitude” in the face of the hugely beneficial result speaks of an entire class culture that had at its heart a group resolution neither to understand nor to explain.

As the years have passed, the contradictions within conservatism have seemed to reach some kind of breaking point at which it is very hard to see how its central tenets can continue to make sense. Admittedly, since the severe recession brought about by the banks, Conservative administrations have found favour with the electorate while Labour has languished. At the election a year ago, Conservatives did somehow scrape together votes from almost 24% of the electorate. But such an outcome has done nothing to shake my basic conviction. In its essential thinking, the Tory project is bust.

The origins of conservatism’s modern incoherence lie with Thatcher. Whatever your view of her influence, she was different from her predecessors in her degree of intellectuality. She was unusually interested in ideas. Groomed by Chicago economists, she believed that Britain, robbed of the easy commercial advantages of its imperial reach, could thenceforth only prosper if it became competitive with China, with Japan, with America and with Germany. For this reason, in 1979, a crackpot theory called monetarism was briefly put into practice and allowed to wreak the havoc that destroyed one fifth of British industry. As soon as this futile theory had been painfully discredited, Conservative minds switched to obsessing on what they really wanted: the promotion and propagation of the so-called free market. If a previous form of patrician conservatism had been about respectability and social structure, this new form was about replacing all notions of public enterprise with a striving doctrine of individualism.

It is painful to point out how completely this grafting of foreign ideas onto the British economy has failed. The financial crash of 2008 dispelled once and for all the ingenious theory of the free market. The only thing, ideologues had argued, that could distort a market was the imposition of unnecessary rules and regulations by a third party, which had no vested interest in the outcome of the transaction and that was therefore a meddling force that robbed markets of their magnificent, near-mystical wisdom. These meddling forces were called governments. The flaw in the theory became apparent as soon as it was proved, once and for all, that irresponsible behaviour in a market did not simply affect the parties involved but could also, thanks to the knock-on effects of modern derivatives, bring whole national economies to their knees. The crappy practices of the banks did not punish only the guilty. Over and over, they punished the innocent far more cruelly. The myth of the free market had turned out to be exactly that: a myth, a Trotsykite fantasy, not real life.

Even disciples of Milton Friedman in Chicago were willing to admit the scale of the rout. They openly used the words “Back to the drawing board”. But in an astonishing act of corporate blackmail, the banks themselves then insisted that they be subsidised by the state. The very same taxpayers whom they had just defrauded had to dig in their pockets to pay for the bankers’ offences. Although state aid could no longer be tolerated as a good thing for regular citizens, who, it was said, were prone to becoming depraved, spoilt and junk-food-dependent when offered free money, subsidy could still be offered, when needed, on a dazzling scale, to benefit those who were already among our country’s most privileged and who were, by coincidence, the sole progenitors of its economic collapse. What a stroke of luck! Socialism, too good for the poor, turned out to be just the ticket for the rich.

It was the Labour government of Gordon Brown that consented to this first act of blackmail. It had little choice. There were dark threats from the banks of taking the whole country down with them. But it was the City-friendly Conservatives, learning nothing from history, who caved in without protest to a second, more outrageous wave of blackmail. The banks that had led us into the recession then argued that they were the only people who could lead us out. And the only way they could restore prosperity, they insisted, was by returning unpunished to exactly the same practices that had precipitated the crisis in the first place.

It has become impossible for any Conservative to argue for a free market when they do everything in their power to forbid free movement of labour. One is impossible without the other. A market, by definition, cannot be free if it operates behind artificial walls, or if it deliberately excludes traders who can offer their goods and services at a more competitive price. At the moment many such traders are volunteering to arrive and lend our market exactly the vigour that Conservatives always say it needs. But all too many of them, whether from Aleppo or from Tripoli, are dying with their children in open boats in the Mediterranean because the home secretary, Theresa May, is telling them that when she talks of the “free market”, she doesn’t actually mean it. She means “protected market”. She means “our market”. She means “market for people like us”. How can anyone with a trace of consistency or personal honour stand up and declare that international competitiveness is the sole criterion of national success, while at the same time excluding from that competition anyone who can compete better than you? Economic migrants, showing exactly the qualities of risk-taking, courage, independence, and family responsibility that Conservatives affect to admire are invited by May to plunge to their deaths in the sea rather than to trade.

The outcome of the Conservatives’ 30-year love affair with the idea that Britain is at heart no different from China, †he US or Germany, has inevitably been a sense of threat to the idea of national identity. Once Thatcher surrendered a native British conservatism to an American one, she knew full well that the side-effect would be to destroy ties and communities that held society together. By her own policies, she was reduced to petulant gestures. At Downing Street receptions she replaced the despised Perrier with good British Malvern water, but nobody was fooled. If international capital did indeed rule the world, then nothing made Britain special. On the contrary, it was on its way to being little more than a brand, defined, presumably, by the union jack, Cilla Black, Shakespeare, Jimmy Savile, Merrydown cider, and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. “We are a grandmother,” offered to cameras in the street on the birth of her first grandchild, represented a grammatical formulation halfway between patriotism and lunacy, intended to suggest the unique syntactical glamour of the English language. With the flick of a single pronoun, anyone could make themselves royalty. But on Thatcher’s watch, Britishness was now just bunting, a Falklands mug, a pretence.

Knuckle was a youthful pastiche of an American thriller, relocating the myth of the hard-boiled private eye incongruously into the home counties. Curly Delafield, a young arms dealer, returns to Guildford in order to try and find his sister Sarah who has disappeared. But in the process he finds himself freshly infuriated by the civilised hypocrisy of his father Patrick Delafield, a stockbroker of the old school. In the play father and son represent two contrasting strands in conservatism. Patrick, the father, is cultured, quiet and responsible. Curly, the son, is aggressive, buccaneering and loud. One of them sees the creation of wealth as a mature duty to be discharged for the benefit of the whole community, with the aim of perpetuating a way of life that has its own distinctive character and tradition. But the other character, based on various criminal or near-criminal racketeers who were beginning to play a more prominent role in British finance in the 1970s, sees such thinking as outdated. Curly’s own preference is to make as much money as he can in as many fields as he can and then to get out fast.

The first thing to notice about my play is that it was written in 1973. Margaret Thatcher was not elected until six years later. So whatever the impact of her arrival at the end of decade, it would be wrong to say that she brought anything very new to a Tory schism that had been latent for years. Surely, she showed power and conviction in advancing the cause of the Curly Delafield version of capitalism – no good Samaritan could operate, she once argued, unless the Samaritan were filthy rich in the first place. How else to explain the fact that the very split that she formally confronted in the different mindsets within her government – she named the two opposing sides “wets” and “drys” – was explored in my work at the Oxford Playhouse more than five years before? In 1951, resolving never to vote for them again, the novelist Evelyn Waugh had complained that the Conservative party in his lifetime “had never put the clock back a single second”. But the administrations that Thatcher first led and then inspired have never shown interest in conserving anything at all. The giveaway, for once, has not been in the name.

You may say that the party aims, like all such parties, to keep the well off well off. That, never forget, is any rightwing grouping’s conservative mission, which will offer a blindingly simple explanation for the larger part of its behaviour. And for obvious reasons, the money party in this particular culture has also aimed to perpetuate the narcotic influence of the monarchy. But with these two exceptions, it is hard to think of any area of public activity – education, justice, defence, health, culture – which any of the last seven Conservative governments have been interested in protecting, let alone conserving. On the contrary, they have preferred a state of near‑Maoist revolution, complaining that, in an extraordinary coincidence, almost every aspect of British life except retail and finance is incompetently organised. Who could have imagined it? And after all those dominant Conservative governments! In this belief, they have launched waves of attacks against teachers, doctors, nurses, policemen and women, soldiers, social workers, civil servants, local councillors, firefighters, broadcasters and transport workers – all of whom they openly scorn for the mortal sin of not being financiers or entrepreneurs.

For a party that is meant to like people, and to believe in enabling them, the modern Conservative party, once inclusive, has had, to say the least, a funny way of showing it. From every government department we regularly expect sallies against the very people who toil in the sector that the minister is supposed to lead. If there were at this moment a Ministry of Fruit Picking, you can be damn sure that the only way an ambitious Tory minister could advance his career would be by launching a blistering attack on the feckless indolence and inefficiency of fruit pickers.

It would be dishonest, however, to pretend any kind of nostalgia for the earlier, smugger form of conservatism. It is commonly said that leaders such as Harold Macmillan had either fought in the trenches or known men at first hand in their industrial constituencies and so gained a respect for working-class life, which the 21st-century leadership, with its upmarket aura of fine wine and evenings spent manspreading with sofa-sprawled box sets, conspicuously lacks. But this is to ignore the repellent layer of snobbery on which such sympathy relied. Even if, like me, you find the modern snobbery of a Notting Hill Cameron, who would rather be seen to be cool than to be caught out being compassionate, even more disgusting than the old-fashioned kind – because it is so much more cynical and calculated – nevertheless there was in the blimpish tone of the old conservatism an air of right-to-rule that saw the country as its plaything and government as its entitlement. Winston Churchill’s outrage at being booted out at the end of the second world war and the ruling class’s linking of the words “inexplicable” and “ingratitude” in the face of the hugely beneficial result speaks of an entire class culture that had at its heart a group resolution neither to understand nor to explain.

As the years have passed, the contradictions within conservatism have seemed to reach some kind of breaking point at which it is very hard to see how its central tenets can continue to make sense. Admittedly, since the severe recession brought about by the banks, Conservative administrations have found favour with the electorate while Labour has languished. At the election a year ago, Conservatives did somehow scrape together votes from almost 24% of the electorate. But such an outcome has done nothing to shake my basic conviction. In its essential thinking, the Tory project is bust.

The origins of conservatism’s modern incoherence lie with Thatcher. Whatever your view of her influence, she was different from her predecessors in her degree of intellectuality. She was unusually interested in ideas. Groomed by Chicago economists, she believed that Britain, robbed of the easy commercial advantages of its imperial reach, could thenceforth only prosper if it became competitive with China, with Japan, with America and with Germany. For this reason, in 1979, a crackpot theory called monetarism was briefly put into practice and allowed to wreak the havoc that destroyed one fifth of British industry. As soon as this futile theory had been painfully discredited, Conservative minds switched to obsessing on what they really wanted: the promotion and propagation of the so-called free market. If a previous form of patrician conservatism had been about respectability and social structure, this new form was about replacing all notions of public enterprise with a striving doctrine of individualism.

It is painful to point out how completely this grafting of foreign ideas onto the British economy has failed. The financial crash of 2008 dispelled once and for all the ingenious theory of the free market. The only thing, ideologues had argued, that could distort a market was the imposition of unnecessary rules and regulations by a third party, which had no vested interest in the outcome of the transaction and that was therefore a meddling force that robbed markets of their magnificent, near-mystical wisdom. These meddling forces were called governments. The flaw in the theory became apparent as soon as it was proved, once and for all, that irresponsible behaviour in a market did not simply affect the parties involved but could also, thanks to the knock-on effects of modern derivatives, bring whole national economies to their knees. The crappy practices of the banks did not punish only the guilty. Over and over, they punished the innocent far more cruelly. The myth of the free market had turned out to be exactly that: a myth, a Trotsykite fantasy, not real life.

Even disciples of Milton Friedman in Chicago were willing to admit the scale of the rout. They openly used the words “Back to the drawing board”. But in an astonishing act of corporate blackmail, the banks themselves then insisted that they be subsidised by the state. The very same taxpayers whom they had just defrauded had to dig in their pockets to pay for the bankers’ offences. Although state aid could no longer be tolerated as a good thing for regular citizens, who, it was said, were prone to becoming depraved, spoilt and junk-food-dependent when offered free money, subsidy could still be offered, when needed, on a dazzling scale, to benefit those who were already among our country’s most privileged and who were, by coincidence, the sole progenitors of its economic collapse. What a stroke of luck! Socialism, too good for the poor, turned out to be just the ticket for the rich.

It was the Labour government of Gordon Brown that consented to this first act of blackmail. It had little choice. There were dark threats from the banks of taking the whole country down with them. But it was the City-friendly Conservatives, learning nothing from history, who caved in without protest to a second, more outrageous wave of blackmail. The banks that had led us into the recession then argued that they were the only people who could lead us out. And the only way they could restore prosperity, they insisted, was by returning unpunished to exactly the same practices that had precipitated the crisis in the first place.

It has become impossible for any Conservative to argue for a free market when they do everything in their power to forbid free movement of labour. One is impossible without the other. A market, by definition, cannot be free if it operates behind artificial walls, or if it deliberately excludes traders who can offer their goods and services at a more competitive price. At the moment many such traders are volunteering to arrive and lend our market exactly the vigour that Conservatives always say it needs. But all too many of them, whether from Aleppo or from Tripoli, are dying with their children in open boats in the Mediterranean because the home secretary, Theresa May, is telling them that when she talks of the “free market”, she doesn’t actually mean it. She means “protected market”. She means “our market”. She means “market for people like us”. How can anyone with a trace of consistency or personal honour stand up and declare that international competitiveness is the sole criterion of national success, while at the same time excluding from that competition anyone who can compete better than you? Economic migrants, showing exactly the qualities of risk-taking, courage, independence, and family responsibility that Conservatives affect to admire are invited by May to plunge to their deaths in the sea rather than to trade.

The outcome of the Conservatives’ 30-year love affair with the idea that Britain is at heart no different from China, †he US or Germany, has inevitably been a sense of threat to the idea of national identity. Once Thatcher surrendered a native British conservatism to an American one, she knew full well that the side-effect would be to destroy ties and communities that held society together. By her own policies, she was reduced to petulant gestures. At Downing Street receptions she replaced the despised Perrier with good British Malvern water, but nobody was fooled. If international capital did indeed rule the world, then nothing made Britain special. On the contrary, it was on its way to being little more than a brand, defined, presumably, by the union jack, Cilla Black, Shakespeare, Jimmy Savile, Merrydown cider, and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. “We are a grandmother,” offered to cameras in the street on the birth of her first grandchild, represented a grammatical formulation halfway between patriotism and lunacy, intended to suggest the unique syntactical glamour of the English language. With the flick of a single pronoun, anyone could make themselves royalty. But on Thatcher’s watch, Britishness was now just bunting, a Falklands mug, a pretence.

A protest outside the Home Office against the Conservative government’s immigration policies, in 2015. Photograph: Guy Corbishley/Alamy

Since then, successive Conservative governments have agonised long-windedly about the problem of how to make citizens loyal to a nation at the very moment when they are declaring the primacy of the economic system over the local culture. Their words die as soon as spoken, because everyone can see that if a government is unwilling to lift a finger to save those few organisations – like, for example, the steel industry – that do indeed forge communities, then all their rhetoric is so much guff. The home secretary, hitting syllables with a hammer as to a backward class of four year-olds, gloweringly asks everyone to share what she calls “British values”. Yet her own values, which she shares with the gilded David Cameron and George Osborne, include support for drone strikes and targeted assassination, the right to intercept private communications, the intention to curtail freedom of speech, the imposition of impossible limits on industrial action, a fierce contempt for any of the sick or unfortunate who have relied on the support of the state in order to stay alive, and a policy of selling lethal weapons to totalitarian allies who use them to bomb schools. The home secretary contemplates with equanimity the figure of the 2,380 disabled people who died in the little more than two years following Ian Duncan Smith’s legislation that recategorised them as “fit to work”. I don’t. By these standards, am I even British? Do I “share values” with Theresa May? Do I hell.

There will certainly be those who think me wistful in imagining that just because a headbangers’ conservatism no longer makes any intellectual sense that it is therefore finished. You will point, correctly, to the resilience of the Tory party and its ability to adapt at all times to changing circumstance. In the autumn of 2015, Jeremy Hunt, the health secretary, ready to warn us of what he insisted with relish were the harsh realities of global capitalism – Oh God, how Tories love saying “harsh realities” – insisted that Britain could only compete with China if it lowered state benefits and slashed tax credits for working people. It was, he said, essential for our whole future as a nation. But when George Osborne, the chancellor of the exchequer, then reversed his announced plan to slash those tax credits because such slashing would have represented a threat to his own advancement to Downing Street, that same Jeremy Hunt fell, on the instant, conspicuously silent.

It is, you may think, exactly such calculating practicality that is keeping the Tory ship floating long after its engine has died. You will add that the problems of how individual cultures are to endure the assaults of global corporations are, after all, not confined to Britain. Even if the government were of a radically different colour, you may say, it too would be facing the almost impossible challenge of asking how any country is to maintain meaningful democracy in the face of a predatory capitalism run by a kleptocratic class, which feels entitled to skim money at will. Would any faction honestly do better than the Tories at dealing with businesses run for no other purpose than the personal enrichment of their executives?

David Cameron arrived in office aware that a conservatism that was purely economic could not possibly meet the needs of the country, and therefore chose to advance an unlikely system of volunteerism, which he called the “big society”. It was, self-evidently, a palliative, nothing more, the lazy shrug of a faltering conscience, and one that predictably lasted no longer than the life cycle of a mosquito. Alert to a problem, Cameron lacked the fortitude to pursue its solution. Instead, Conservative ministers have fallen back on the more familiar, far more routine strategy of sour rhetoric, petulantly blaming the people for their failure to live up to the promise of their leaders’ policies. Do you have to be my age to remember a time when politicians aimed to lead, rather than to lecture? Is anyone old enough to recall a government whose ostensible mission was to serve us, not to improve us? When did magnanimity cease to be one of those famous British virtues we are ordered to share?

Since then, successive Conservative governments have agonised long-windedly about the problem of how to make citizens loyal to a nation at the very moment when they are declaring the primacy of the economic system over the local culture. Their words die as soon as spoken, because everyone can see that if a government is unwilling to lift a finger to save those few organisations – like, for example, the steel industry – that do indeed forge communities, then all their rhetoric is so much guff. The home secretary, hitting syllables with a hammer as to a backward class of four year-olds, gloweringly asks everyone to share what she calls “British values”. Yet her own values, which she shares with the gilded David Cameron and George Osborne, include support for drone strikes and targeted assassination, the right to intercept private communications, the intention to curtail freedom of speech, the imposition of impossible limits on industrial action, a fierce contempt for any of the sick or unfortunate who have relied on the support of the state in order to stay alive, and a policy of selling lethal weapons to totalitarian allies who use them to bomb schools. The home secretary contemplates with equanimity the figure of the 2,380 disabled people who died in the little more than two years following Ian Duncan Smith’s legislation that recategorised them as “fit to work”. I don’t. By these standards, am I even British? Do I “share values” with Theresa May? Do I hell.

There will certainly be those who think me wistful in imagining that just because a headbangers’ conservatism no longer makes any intellectual sense that it is therefore finished. You will point, correctly, to the resilience of the Tory party and its ability to adapt at all times to changing circumstance. In the autumn of 2015, Jeremy Hunt, the health secretary, ready to warn us of what he insisted with relish were the harsh realities of global capitalism – Oh God, how Tories love saying “harsh realities” – insisted that Britain could only compete with China if it lowered state benefits and slashed tax credits for working people. It was, he said, essential for our whole future as a nation. But when George Osborne, the chancellor of the exchequer, then reversed his announced plan to slash those tax credits because such slashing would have represented a threat to his own advancement to Downing Street, that same Jeremy Hunt fell, on the instant, conspicuously silent.

It is, you may think, exactly such calculating practicality that is keeping the Tory ship floating long after its engine has died. You will add that the problems of how individual cultures are to endure the assaults of global corporations are, after all, not confined to Britain. Even if the government were of a radically different colour, you may say, it too would be facing the almost impossible challenge of asking how any country is to maintain meaningful democracy in the face of a predatory capitalism run by a kleptocratic class, which feels entitled to skim money at will. Would any faction honestly do better than the Tories at dealing with businesses run for no other purpose than the personal enrichment of their executives?

David Cameron arrived in office aware that a conservatism that was purely economic could not possibly meet the needs of the country, and therefore chose to advance an unlikely system of volunteerism, which he called the “big society”. It was, self-evidently, a palliative, nothing more, the lazy shrug of a faltering conscience, and one that predictably lasted no longer than the life cycle of a mosquito. Alert to a problem, Cameron lacked the fortitude to pursue its solution. Instead, Conservative ministers have fallen back on the more familiar, far more routine strategy of sour rhetoric, petulantly blaming the people for their failure to live up to the promise of their leaders’ policies. Do you have to be my age to remember a time when politicians aimed to lead, rather than to lecture? Is anyone old enough to recall a government whose ostensible mission was to serve us, not to improve us? When did magnanimity cease to be one of those famous British virtues we are ordered to share?

Prime Minister David Cameron makes a speech on the ‘big society’ in 2011. Photograph: WPA Pool/Getty Images

Commentators excoriate the politics of envy, but the politics of spite gets a free pass. Jeremy Hunt hates doctors. Theresa May despises the police. John Whittingdale resents public broadcasters. Chris Grayling loathed prison officers and Michael Gove famously had it in for teachers. Nowadays that’s what is called politics and that’s all politicians, Conservative-style, do. They voice grievances against a stubborn electorate that is never as far-seeing or radical as they are. Like Blair before him, Cameron has reduced the act of government to a sort of murmuring grudge, a resentment, in which politicians continually tell the surly people that we lack the necessary virtues for survival in the modern world. They know perfectly well that we hate them, and so their only response is to hate us back. Politics has been reduced to a sort of institutionalised nagging, in which a rack of pampered professionals, cut from the eye of the ruling class, tells everyone else that they don’t “get it”, and that they must “measure up” and “change their ways”. Having discharged their analysis, the preachers then invariably scoot off through wide-open doors to 40th-floor boardrooms to make themselves frictionless fortunes as greasers and lobbyists – or, as they prefer to say, “consultants”.

Of all the privatisations of the last 30 years, none has been more catastrophic than the privatisation of virtue. A doctor recently remarked that she was happy to put up with long hours and underpayment because she knew she was working in the service of an ideal. But, she said, if the NHS were so reorganised that she were then asked to suffer the same degree of overwork to provide profits for some rip-off private health company, she would walk away and refuse. In describing her motivation in this simple way, she put her finger on everything that has gone wrong in Britain under the tyranny of abstract ideas. Why do we work? Who are we working for? As Groucho Marx once asked: “If work’s so great, why don’t the rich do it?” People are ready, happy and willing to do things for our common benefit that they are reluctant to do if it is all in the interests of companies such as British Telecom, Virgin Railways, EDF Energy, Talk Talk, HSBC, Kraft Foods and Barclays Bank, outfits that still have little or no interest in balancing out their prosperity in a fair manner between their employees and their shareholders.

The reason we have been governed so badly is because government has been in the hands of those who least believe in it. Politicians have become little more than go-betweens, their principal function to hand over taxpayers’ assets, always in car boot sales and always at way less than market value. No longer having faith in their own competence, politicians have blithely surrendered the state’s most basic duties. Even the care and detention of prisoners, and thereby the protection of citizens from danger, has been given to contractors, as though the state no longer trusted itself to open a gate, build a wall, or serve a three-course meal. With foreign policy delegated to Washington, and consciences delegated by private contract to callous logistics companies, no wonder the profession of politics in Britain is having a nervous breakdown of its own making.

In the years after the second world war, under successive administrations of either party, we profited from purposeful initiatives, building the welfare state, the housing stock and the NHS. We voted for leaders who shared a common-sense belief that government was necessary to do good. They entered politics partly because they believed in its essential usefulness. How strange it is, then, this new breed of self-hating politicians who want to make a healthy living in politics, while at the same time insisting that the only function of politics is to get out of the way of private enterprise. Ever since Ronald Reagan announced that he would campaign on a platform of smaller government, it has been an article of faith on the right to insist that the state must play an ever smaller part in the country’s affairs. But the paradox of a Thatcher or a Reagan is that they fulminate all the time against the state while living lavishly off it. Our current administration advises everyone else to strip back and face the new demands of austerity. Meanwhile, it employs 68 unelected special advisers to fix Tory policy at taxpayers’ expense, while busily ordering a private jet for the prime minister’s travel.

How did we get here? And how do we move on? Prince Charles, questioning a monk in Kyoto about the road to enlightenment, was asked in reply if he could ever forget that he was a prince. “Of course not,” Charles replied, “One’s always aware of it. One’s always aware one’s a prince.” In that case, said the monk, he would never know the road to enlightenment. A similar need to forget our pretensions must newly govern our politics. We do not live in a free market. No such thing as a free market exists. Nor can it. The world is far too complex, far too interconnected. All markets are rigged. The only question that need concern us is: in whose interest? In the light of this question, obsessive Tory spasms about Europe are revealed as a doomed attempt to re-rig the market even further in their own favour, so that the same exclusion orders that prevent Syrians and Libyans from threatening our carefully protected wealth should in future keep out over-eager Hungarians, Poles, Bulgarians and Romanians. Far from wishing to free the country to compete in the world, anti-European Union sentiment in Britain is, in Tory hearts, about protecting Britain yet more effectively.

The first task British politics has to address is correcting the terrible harm we have done ourselves by assuming that nothing can be achieved through collective enterprise. It is as much a failure of national imagination as it is of national will. When I woke up on the morning after Knuckle opened in London, on 5 March 1974, then the stinging impact of the play’s rejection by audiences and critics alike forced me finally to admit to myself that I was not just a theatre director who happened to write, but that I was, indeed, going to spend the rest of my life as a professional playwright.

In the 1980s and 1990s, my attention turned to the people on the front line who helped bind the wounds of communities shattered by Thatcherism. In plays such as Skylight and Racing Demon and Murmuring Judges, I was able to portray teachers and vicars and police and prison officers who, newly politicised, saw their jobs as trying to tackle the everyday problems caused by a reckless ideology. I loved writing about such hands-on practical people because I admired them. They became my heroes and heroines. But even as I tried to discredit the publicity that saw Thatcherism as liberating, I was still reluctant to propose a counter-myth, which pictured the government of 1945 as a permanent model of perfection. Requested over and again to write films and plays about the National Health Service, I always refused because I was reluctant to make too facile a comparison. How could I write on the subject without seeming to imply that once we had ideals, and that now we didn’t?

Commentators excoriate the politics of envy, but the politics of spite gets a free pass. Jeremy Hunt hates doctors. Theresa May despises the police. John Whittingdale resents public broadcasters. Chris Grayling loathed prison officers and Michael Gove famously had it in for teachers. Nowadays that’s what is called politics and that’s all politicians, Conservative-style, do. They voice grievances against a stubborn electorate that is never as far-seeing or radical as they are. Like Blair before him, Cameron has reduced the act of government to a sort of murmuring grudge, a resentment, in which politicians continually tell the surly people that we lack the necessary virtues for survival in the modern world. They know perfectly well that we hate them, and so their only response is to hate us back. Politics has been reduced to a sort of institutionalised nagging, in which a rack of pampered professionals, cut from the eye of the ruling class, tells everyone else that they don’t “get it”, and that they must “measure up” and “change their ways”. Having discharged their analysis, the preachers then invariably scoot off through wide-open doors to 40th-floor boardrooms to make themselves frictionless fortunes as greasers and lobbyists – or, as they prefer to say, “consultants”.

Of all the privatisations of the last 30 years, none has been more catastrophic than the privatisation of virtue. A doctor recently remarked that she was happy to put up with long hours and underpayment because she knew she was working in the service of an ideal. But, she said, if the NHS were so reorganised that she were then asked to suffer the same degree of overwork to provide profits for some rip-off private health company, she would walk away and refuse. In describing her motivation in this simple way, she put her finger on everything that has gone wrong in Britain under the tyranny of abstract ideas. Why do we work? Who are we working for? As Groucho Marx once asked: “If work’s so great, why don’t the rich do it?” People are ready, happy and willing to do things for our common benefit that they are reluctant to do if it is all in the interests of companies such as British Telecom, Virgin Railways, EDF Energy, Talk Talk, HSBC, Kraft Foods and Barclays Bank, outfits that still have little or no interest in balancing out their prosperity in a fair manner between their employees and their shareholders.

The reason we have been governed so badly is because government has been in the hands of those who least believe in it. Politicians have become little more than go-betweens, their principal function to hand over taxpayers’ assets, always in car boot sales and always at way less than market value. No longer having faith in their own competence, politicians have blithely surrendered the state’s most basic duties. Even the care and detention of prisoners, and thereby the protection of citizens from danger, has been given to contractors, as though the state no longer trusted itself to open a gate, build a wall, or serve a three-course meal. With foreign policy delegated to Washington, and consciences delegated by private contract to callous logistics companies, no wonder the profession of politics in Britain is having a nervous breakdown of its own making.

In the years after the second world war, under successive administrations of either party, we profited from purposeful initiatives, building the welfare state, the housing stock and the NHS. We voted for leaders who shared a common-sense belief that government was necessary to do good. They entered politics partly because they believed in its essential usefulness. How strange it is, then, this new breed of self-hating politicians who want to make a healthy living in politics, while at the same time insisting that the only function of politics is to get out of the way of private enterprise. Ever since Ronald Reagan announced that he would campaign on a platform of smaller government, it has been an article of faith on the right to insist that the state must play an ever smaller part in the country’s affairs. But the paradox of a Thatcher or a Reagan is that they fulminate all the time against the state while living lavishly off it. Our current administration advises everyone else to strip back and face the new demands of austerity. Meanwhile, it employs 68 unelected special advisers to fix Tory policy at taxpayers’ expense, while busily ordering a private jet for the prime minister’s travel.

How did we get here? And how do we move on? Prince Charles, questioning a monk in Kyoto about the road to enlightenment, was asked in reply if he could ever forget that he was a prince. “Of course not,” Charles replied, “One’s always aware of it. One’s always aware one’s a prince.” In that case, said the monk, he would never know the road to enlightenment. A similar need to forget our pretensions must newly govern our politics. We do not live in a free market. No such thing as a free market exists. Nor can it. The world is far too complex, far too interconnected. All markets are rigged. The only question that need concern us is: in whose interest? In the light of this question, obsessive Tory spasms about Europe are revealed as a doomed attempt to re-rig the market even further in their own favour, so that the same exclusion orders that prevent Syrians and Libyans from threatening our carefully protected wealth should in future keep out over-eager Hungarians, Poles, Bulgarians and Romanians. Far from wishing to free the country to compete in the world, anti-European Union sentiment in Britain is, in Tory hearts, about protecting Britain yet more effectively.

The first task British politics has to address is correcting the terrible harm we have done ourselves by assuming that nothing can be achieved through collective enterprise. It is as much a failure of national imagination as it is of national will. When I woke up on the morning after Knuckle opened in London, on 5 March 1974, then the stinging impact of the play’s rejection by audiences and critics alike forced me finally to admit to myself that I was not just a theatre director who happened to write, but that I was, indeed, going to spend the rest of my life as a professional playwright.

In the 1980s and 1990s, my attention turned to the people on the front line who helped bind the wounds of communities shattered by Thatcherism. In plays such as Skylight and Racing Demon and Murmuring Judges, I was able to portray teachers and vicars and police and prison officers who, newly politicised, saw their jobs as trying to tackle the everyday problems caused by a reckless ideology. I loved writing about such hands-on practical people because I admired them. They became my heroes and heroines. But even as I tried to discredit the publicity that saw Thatcherism as liberating, I was still reluctant to propose a counter-myth, which pictured the government of 1945 as a permanent model of perfection. Requested over and again to write films and plays about the National Health Service, I always refused because I was reluctant to make too facile a comparison. How could I write on the subject without seeming to imply that once we had ideals, and that now we didn’t?

Michael Gambon and Lia Williams in David Hare’s play Skylight, in 1996. Photograph: Joan Marcus/AP/AP

Our current politics are governed by two competing nostalgias, both of them pieties. Conservatives seek to locate all good in Thatcherism and the 1980s, and in the unworkable nonsense of the free market, while Labour seeks to locate it in 1945 and an industrial society, which, for better or worse, no longer exists. And yet issues of justice remain, and always will. Conservativism, as presently formulated, is unworkable in the UK because it continues to demand that citizens from so many different backgrounds and cultures identify with a society organised in ways that are outrageously unfair. The bullying rhetorical project of seeking to blame diversity for the crimes of inequity is doomed to fail. You cannot pamper the rich, punish the poor, cut benefits and then say: “Now feel British!”

There is a bleak fatalism at the heart of conservatism, which has been codified into the lie that the market can only do what the market does, and that we must therefore watch powerless. We have seen the untruth of this in the successful interventions governments have recently made on behalf of the rich. Now we long for many more such interventions on behalf of everyone else. Often, in the past 40 years, I refused to contemplate writing plays that might imply that public idealism was dead. From observing the daily lives of those in public service, I know this not to be true. But we lack two things: new ways of channelling such idealism into practical instruments of policy, and a political class that is not disabled by its philosophy from the job of realising them. If we talk seriously about British values, then the noblest and most common of them all used to be the conviction that, with will and enlightenment, historical change could be managed. We did not have to be its victims. Its cruelties could be mitigated. Why, then, is the current attitude that we must surrender to it? I had asked this question at the Oxford Playhouse in 1974 as I walked back down a darkened Beaumont Street to a hotel of draped velvet curtains, power outages and guttering candles. I ask it again today.

Our current politics are governed by two competing nostalgias, both of them pieties. Conservatives seek to locate all good in Thatcherism and the 1980s, and in the unworkable nonsense of the free market, while Labour seeks to locate it in 1945 and an industrial society, which, for better or worse, no longer exists. And yet issues of justice remain, and always will. Conservativism, as presently formulated, is unworkable in the UK because it continues to demand that citizens from so many different backgrounds and cultures identify with a society organised in ways that are outrageously unfair. The bullying rhetorical project of seeking to blame diversity for the crimes of inequity is doomed to fail. You cannot pamper the rich, punish the poor, cut benefits and then say: “Now feel British!”

There is a bleak fatalism at the heart of conservatism, which has been codified into the lie that the market can only do what the market does, and that we must therefore watch powerless. We have seen the untruth of this in the successful interventions governments have recently made on behalf of the rich. Now we long for many more such interventions on behalf of everyone else. Often, in the past 40 years, I refused to contemplate writing plays that might imply that public idealism was dead. From observing the daily lives of those in public service, I know this not to be true. But we lack two things: new ways of channelling such idealism into practical instruments of policy, and a political class that is not disabled by its philosophy from the job of realising them. If we talk seriously about British values, then the noblest and most common of them all used to be the conviction that, with will and enlightenment, historical change could be managed. We did not have to be its victims. Its cruelties could be mitigated. Why, then, is the current attitude that we must surrender to it? I had asked this question at the Oxford Playhouse in 1974 as I walked back down a darkened Beaumont Street to a hotel of draped velvet curtains, power outages and guttering candles. I ask it again today.

"I want you to go to bed at night and know when you are playing South Africa tomorrow you have to face me"

"I want you to go to bed at night and know when you are playing South Africa tomorrow you have to face me"

Shane Warne could clear his mind of an unsuccessful previous ball to attack afresh with the next © Getty Images

Shane Warne could clear his mind of an unsuccessful previous ball to attack afresh with the next © Getty Images