A glut of oil, the demise of Opec and weakening global demand combined to make 2015 the year of crashing oil prices. The cost of crude fell to levels not seen for 11 years – and the decline may have further to go.

There have been four sharp increases in the price of oil in the past four decades – in 1973, 1979, 1990 and 2008 – and each has led to a global recession. By that measure, a lower oil price should be positive for the world economy, with lower fuel costs for consumers and businesses in those countries that import crude outweighing the losses to producing nations.

But the evidence since oil prices started falling from their peak of $115 a barrel in August 2014 has not supported that thesis – or not yet. Oil producers have certainly felt the impact of the lower prices on their growth rates, their trade figures and their public finances but there has been no surge in consumer spending or business investment elsewhere.

Economist still reckon there will be a boost from a lower oil price particularly if it looks as if the lower cost of crude will be sustained.

Dhaval Joshi, an economist at BCA, a London-based research company, said: “A commodity bubble has deflated three times in the past 100 years: the first was after world war one; the second was after the 1980s oil shock; the third is happening right now.”

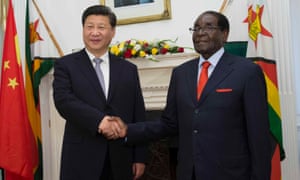

For the big producer countries, this is a major headache, the ramifications of which are only starting to be felt. Oil powers base their spending plans on an assumed crude price. The graphic below shows just how far below water their budgets are.

Joshi says crude prices may fall by a further 35% to reach its long-term trend. That would mean an oil price closer to $25 a barrel - and fiscal crises in some of the world’s most pivotal economies.

Saudi Arabia

The Ras Tanura oil production plant in Saudi Arabia’s eastern province. Photograph: Bilal Qabalan/AFP/Getty Images

Low oil prices are not just squeezing Saudi Arabia’s domestic budget, imposing austerity on a kingdom not used to it: it is taking its toll on Saudi support for foreign projects too.

The kingdom this week announced swingeing budget cuts for 2016 to address an alarming deficit of 15% of GDP run up this year. Subsidies for water, electricity and petroleum products are likely to be cut, and government projects reined in.

But overseas beneficiaries will face some austerity too. For years, Saudi Arabia has used its oil wealth to support friends and allies around the world, including media organisations, thinktanks, academic institutions, religious schools and charities. Countries that have traditionally benefited from Saudi largesse include Jordan, Lebanon, Bahrain, Palestine and Egypt.

But now the IMF has raised the prospect that Saudi Arabia could go bankrupt in five years without changes to its economic policy, cuts in support to foreign allies seem inevitable.

Egypt’s black-hole economy is potentially the kingdom’s most expensive foreign policy commitment. In recent years, Saudi Arabia has donated billions in cash and oil products but, despite this, the Egyptian economy, battered by war, terrorism and political instability, is facing an acute foreign currency shortage.

Speculation is mounting that Saudi financial support to Egypt is starting to dry up – something the Egyptian authorities have denied – and that this is damaging the bilateral relationship.

There have been some signs of tension. In July, Egypt’s oil minister said he had no objections to importing crude oil from Iran, a move sure to ruffle the Saudis. In September, the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi – known for his closeness to the Saudi state – raised eyebrows when he said the new Egyptian culture minister, Hilmi al-Namnam, who is well known for his secularism and dislike of Wahhabi Islam, should never have been appointed.

So far, the Saudi authorities have given few clear signs about how they are planning to respond to the oil price crisis, let alone lay out a long-term plan for a post-oil Saudi Arabia.

Options under consideration are thought to include cutting construction projects, energy subsidies and public sector wages, introducing new taxes and privatisations, and issuing debt.

Another possibility foreign observers have posited is that the Saudis will be forced to unpeg the riyal from the dollar, although given the potential this would have for uncontrollable knock-on effects on the rest of the economy, this seems likely to be a last resort.

Cuts impacting on ordinary Saudis are something the government will be keen to avoid to maintain political stability, so industry, the public sector and foreign allies are likely to bear the brunt of the economic burden.

Nigeria

Nigeria’s president, Muhammadu Buhari, swears in his cabinet in November. Photograph: Afolabi Sotunde/Reuters

The oil price slump has not prevented Nigeria’s new government from unveiling big spending plans – but analysts warn that the generosity is misplaced at a time when oil prices languish below $40 a barrel.

Nigeria is Africa’s top oil producer and the World Bank estimates crude sales fund about 75% of the country’s budget.

In its £19.8bn budget proposal, the government plans to increase spending by about one quarter over last year’s budget, and to pay for it by improving tax collection and cutting the cost of government.

The budget includes £1.65bn for cash transfers to poor Nigerians. The programme was a campaign promise of the president, Muhammadu Buhari, who was elected in March on a platform of cutting corruption and weaning Nigeria’s economy off its dependence on oil revenue.

But some analysts think the proposed budget is unrealistic during times of $40 oil.

“This brings a dose of reality to a people who have extremely high expectations,” said Bismarck Rewane, the chief executive of Financial Derivatives Co. He predicted the government would have to back down on some of its promises.

Nigeria is Africa’s largest economy, but most of the money is concentrated in the hands of a wealthy elite and about two-thirds of Nigerians live in poverty, according to the United Nations development programme.

Analysis Nigeria overtakes South Africa to become Africa's largest economy. Complicated statistical recalculation adds $240bn to the economy - the equivalent of finding six Ghanas within Nigeria, says Tolu Ogunlesi

Unemployment has climbed this year, hitting 9.9% in the third quarter, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

Chuba Ezekwesili, research analyst at Nigerian Economic Summit Group, says despite the falling price of crude, the country has been able to avoid a jump in inflation by imposing limits on the availability of foreign currency.

While other major oil producing economies have let their currencies lose value along with oil prices, Nigeria has spent its reserves to prop up the value of the naira. But Ezekwesili says they can only do that for so long.

“They’re sort of delaying the inevitable,” he said. “I feel like eventually it has to give way, and by the time it does I feel the economy is going to be hurt because a lot of businesses can’t work under those conditions.”

Ezekwesili was also sceptical of the government’s ability to generate the revenue necessary to pay for programmes such as cash transfers to the poor. He doubts the government can accomplish its goals of streamlining its costs and generating more revenue by next year.

“One thing I’ve learned about policies in Nigeria is we tend to be very optimistic but it never really works out exactly as we want it to,” Ezekwesili said.

Russia

Oil extraction at a Gazprom field in Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia. Photograph: TASS/Barcroft Media

Vladimir Putin goes into 2016 with record approval ratings but the shakiest economic outlook since he took charge. In the 15 years he has been at the helm, 2015 was the first year that real wages registered a decline, something that did not happen even during the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Oil and gas exports make up about half of the Russian budget, and the rouble rate has been strongly linked to the price of oil.

Sanctions against Russia, particularly the ban on Russian banks seeking western credit, combined with falling oil prices in late 2014 to create a perfect storm that demolished the rouble, with the currency losing half of its value against the dollar, reviving memories of previous crashes. The currency regained some of its value by spring, but falling oil prices in autumn have caused it to fall back to lows similar to those it experienced in late 2014.

Rouble in freefall despite rate hike

Falling oil prices were one of the principal reasons for the collapse in the Soviet economy, and some economists are warning of history repeating itself. Riding on a wave of high oil prices for most of his presidency, the Russian president did not expect such a sharp downturn. Last October, Putin said that if the price of oil fell below $80 a barrel, the world economy would crash. A range of other top Russian officials made similar statements, in effect ruling out the possibility that oil could fall below $70.

Some analysts say the rouble is still overvalued, and the current oil price should theoretically push the rouble down further. This is necessary to balance the budget: the fewer dollars Russia receives for the oil it sells, the higher the exchange rate needs to be for the budget to receive the requisite amount of roubles. For the budget to balance at 65 roubles, not far off the current rate, the price of oil should be $70, a recent Bank of America Merrill Lynch report found.

For ordinary Russians, it could be a tough year ahead. Those who were used to travelling abroad have already had to scale back as the rouble made the cost of visiting foreign cities prohibitive; and rising food prices have made it harder to balance the books for many families.

The 2016 budget, fixed in October, requires oil to be at $50 in order to run a 3% deficit within “acceptable” rouble rate limits, meaning if the price does not rise soon, cuts will need to be made or reserves spent. The war in Syria is an extra cost, and the announced increases in military spending are not likely to be reversed.

US

Belridge, California, is one of the oldest and largest oilfields in the US containing tens of thousands of wells, many of which are being fracked. Photograph: Les Stone/Corbis

Filling up at the gas station hasn’t been this cheap in the US since the recession. The nationwide average price of a gallon of regular is now $2.02 (£1.36), down 58 cents from this time last year, according to auto club AAA, and expected to fall further.

Scared that North America’s oil boom threatens its grip, Opec, the oil cartel, stepped up production and forced a price war that has driven oil prices down to below $35 a barrel. US consumers have benefited from lower petrol prices to the tune of about $700 a year, according to the US government, and that money is fuelling consumer spending. According to a recent report from JP Morgan, 80% of that saving is being spent on goods and services.

But the collapsing price of oil has also cast a shadow over the US energy industry – formerly one of the country’s fastest growing employers. Fracking – the controversial process of extracting oil and gas from shale rock – has become less attractive to investors as the oil price has fallen, and tens of thousands of jobs have been lost as a result. This year, the International Energy Agency said low oil prices would “slam the brakes” on the US shale industry and the impact is already being felt across the country’s oil producing areas.

The US energy sector has cut more than 90,000 jobs this year, according to outplacement company Challenger, Gray & Christmas. And while the overall US unemployment rate has continued to fall, in Texas unemployment has risen since August, according to the Bureau of Labour Statistics. In North Dakota, home of the Bakken shale oil field, more than 17% of the mining jobs – which include oil and natural gas – have disappeared in the past year. More jobs look certain to be lost in the coming months.

North of the border in Canada, things are even worse. In Alberta, “the Texas of the north”, job layoffs and the downturn of the economy have been blamed for a 30% rise in suicides between January and June, compared with 2014. In Saskatchewan, another energy-dependent region, there have been 19% more suicides this year.

Daniel Pavilonis, senior commodity broker with RJO Futures, said the situation was only likely to get worse for those employed in the US energy sector. “There are oil tankers just sitting off the coast because we don’t need more supply. We have too much,” he said. “There’s oversupply and a lack of anybody trying to tighten production because they don’t want to lose market share.”

As a result he predicts oil prices will go lower, taking more jobs with it. But for most consumers, it’s a win. Unlike other global economic trends, the oil price fall actually benefits average Americans, said Pavilonis. “This is our money,” he said. “For most people, it’s a good thing.”

Venezuela

A mural depicts President Nicolás Maduro, who, having lost the Venezuelan National Assembly, has a battle to keep economy and his leadership afloat. Photograph: Luis Robayo/AFP/Getty Images

In most of the world, falling oil prices have caused significant reductions in petrol prices. But in the country with the world’s largest oil reserves, the oil glut could force a price rise.

“It’s probably the only place in the world where with oil prices so low, they may raise gasoline prices,” says Pedro Méndez, an informal taxi driver in Caracas, the Venezuelan capital, who fills the tank of his Ford Laser for less than a dollar.

But the lower the price of oil goes, the deeper Venezuela’s economy sinks. It’s near total dependence on crude exports for hard currency has seen the government of president Nicolás Maduro struggling to try keep the economy afloat.

The political effect is already being felt. Gripped by spiraling inflation, chronic shortages of basic goods and a quickly depreciating currency, Venezuelan voters this month gave the opposition an overwhelming majority in the new legislature, which takes office in January.

Each $1 drop in oil prices results in more than $685m in lost yearly oil income for PDVSA, the state-owned oil company, according to analysts.

And every drop in crude prices means less funding for the health, education and housing and other social welfare programmes that won Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez, widespread support for his self-styled “Bolivarian revolution”.

While dwindling oil revenue hurts the social programmes, Antonio Azpurua, a financial consultant with CFS Partners/LA Group, says it could be a blessing in disguise, allowing Venezuela to wean itself of its dependence on crude. “Venezuela needs to take advantage of low oil prices to build its industrial base,” he says.

With a super-majority in the National Assembly, the opposition could reverse some of Maduro’s populist measures, which have contributed to the current economic crisis. They could also choose to raise petrol prices.

Iran

Iranians took to the streets to celebrate the nuclear deal which will mean they can more freely trade their oil. Photograph: Abedin Taherkenareh/EPA

Iran is rushing to implement the landmark nuclear accord in order to cash in on sanctions relief as early as next month, but the plummeting price of oil is tempering its expectations even though its economy has become less dependent on crude sales.

Tehran currently exports 1.1m barrels of oil per a but the Iranian oil minister, Bijan Zanganeh, has announced that the country is aiming to double that amount within six months of sanctions being lifted, hoping it will return to the pre-sanctions level of 2.2m.

Although the EU lifted Iranian sanctions in October after the Vienna nuclear agreement, the measures will only come into effect after what has become known as “implementation day”, the unknown date when the UN nuclear watchdog, IAEA, will verify that Iran has taken the necessary steps as outlined under the nuclear deal. Iran is expediting whatever it can to bring this date forward to as early as January.

In an effort to woo foreign investment in the post-sanctions era, Iran put a set of new lucrative oil and gas contracts, worth more than $30bn, on the market this month. But all these efforts have come at a time when global oil prices are falling as a result of a crude surplus of 2m barrels a day, a phenomenon Tehran blames on the Saudis.

“The drop in oil prices hurts all oil producers, not just Iran,” said Amir Handjani, president of PG International commodities trading services and a member of the board directors of RAK Petroleum.

“Saudi Arabia is very aware that Iran will be able to sell its crude unencumbered by sanctions on the international market very soon and will use all means at its disposal to make sure Iran doesn’t recapture the market share it lost over the past four years,” he said.

“Basically, Riyadh’s message to Tehran is simple: we can endure low oil prices for a while; can you?”

But the experience of years under sanctions has made the Iranian economy “incredibly resilient”, according to Handjani. Iran’s economy faced huge economic problems in recent years due to international sanctions imposed over Tehran’s nuclear programme. Plummeting oil prices only added to economic woes in a country with the world’s fourth-largest oil reserves.

“To be sure, low oil prices deny Tehran much needed revenue but unlike the Saudis, Iran’s economy is not solely dependent on oil exports. Oil revenue accounts for about 15% of Iran’s GDP,” Handjani told the Guardian. Sanctions have forced Iran to diversify its economy, he said. It has a large manufacturing base, IT sector, and robust agro-industries, which make its economy on the whole “much more balanced” than Saudi Arabia.

“The Iranian economy has absorbed so many shocks over the past 36 years, from war to sanctions, that the pain of low oil prices now, as it breaks from international isolation, pales in comparison.”

Without naming Saudi Arabia, Zanganeh said last week that it was clear which country had an excess of supply and that there was “no ambiguity about who they are”. On the occasion of unveiling new oil contracts, the Iranian minister said last month that his country was willing to play a major role in oil supply and was even ready to work with American companies. “The way for the presence of these companies in Iran’s oil industry is open,” he said at the Iran Petroleum Contracts Conference in Tehran.

The deputy managing director of the national Iranian oil company (NIOC) told the Guardian in September that the Iranian government was earning more from tax than oil for the first time in almost half a century as the country shifts its traditional reliance on crude to taxation revenues in the face of falling oil prices. Critics say Iran is unlikely to maintain that equation when the lifting of sanctions allows it to export more oil.

According to Opec, Iran on average was selling oil at $38.92 a barrel in November, $5.63 less than the average in October, which is the worst drop among the group’s members.

Iran is rushing to implement the landmark nuclear accord in order to cash in on sanctions relief as early as next month, but the plummeting price of oil is tempering its expectations even though its economy has become less dependent on crude sales.

Tehran currently exports 1.1m barrels of oil per a but the Iranian oil minister, Bijan Zanganeh, has announced that the country is aiming to double that amount within six months of sanctions being lifted, hoping it will return to the pre-sanctions level of 2.2m.

Although the EU lifted Iranian sanctions in October after the Vienna nuclear agreement, the measures will only come into effect after what has become known as “implementation day”, the unknown date when the UN nuclear watchdog, IAEA, will verify that Iran has taken the necessary steps as outlined under the nuclear deal. Iran is expediting whatever it can to bring this date forward to as early as January.

In an effort to woo foreign investment in the post-sanctions era, Iran put a set of new lucrative oil and gas contracts, worth more than $30bn, on the market this month. But all these efforts have come at a time when global oil prices are falling as a result of a crude surplus of 2m barrels a day, a phenomenon Tehran blames on the Saudis.

“The drop in oil prices hurts all oil producers, not just Iran,” said Amir Handjani, president of PG International commodities trading services and a member of the board directors of RAK Petroleum.

“Saudi Arabia is very aware that Iran will be able to sell its crude unencumbered by sanctions on the international market very soon and will use all means at its disposal to make sure Iran doesn’t recapture the market share it lost over the past four years,” he said.

“Basically, Riyadh’s message to Tehran is simple: we can endure low oil prices for a while; can you?”

But the experience of years under sanctions has made the Iranian economy “incredibly resilient”, according to Handjani. Iran’s economy faced huge economic problems in recent years due to international sanctions imposed over Tehran’s nuclear programme. Plummeting oil prices only added to economic woes in a country with the world’s fourth-largest oil reserves.

“To be sure, low oil prices deny Tehran much needed revenue but unlike the Saudis, Iran’s economy is not solely dependent on oil exports. Oil revenue accounts for about 15% of Iran’s GDP,” Handjani told the Guardian. Sanctions have forced Iran to diversify its economy, he said. It has a large manufacturing base, IT sector, and robust agro-industries, which make its economy on the whole “much more balanced” than Saudi Arabia.

“The Iranian economy has absorbed so many shocks over the past 36 years, from war to sanctions, that the pain of low oil prices now, as it breaks from international isolation, pales in comparison.”

Without naming Saudi Arabia, Zanganeh said last week that it was clear which country had an excess of supply and that there was “no ambiguity about who they are”. On the occasion of unveiling new oil contracts, the Iranian minister said last month that his country was willing to play a major role in oil supply and was even ready to work with American companies. “The way for the presence of these companies in Iran’s oil industry is open,” he said at the Iran Petroleum Contracts Conference in Tehran.

The deputy managing director of the national Iranian oil company (NIOC) told the Guardian in September that the Iranian government was earning more from tax than oil for the first time in almost half a century as the country shifts its traditional reliance on crude to taxation revenues in the face of falling oil prices. Critics say Iran is unlikely to maintain that equation when the lifting of sanctions allows it to export more oil.

According to Opec, Iran on average was selling oil at $38.92 a barrel in November, $5.63 less than the average in October, which is the worst drop among the group’s members.

Libya

Fuel depots and tankers have been targets for years in the struggle for control of Libya and its oil resources. Photograph: EPA

Plunging oil prices are threatening disaster in Libya, where civil war has left the population depending on fast-dwindling oil revenues to survive.

Libya has Africa’s largest oil reserves and in normal times this provides 95% of the country’s export revenues, keeping the economy afloat. But civil war between rival governments at either end of the country has shattered the economy, leaving the population almost wholly dependent on revenue generated overseas.

The crash in oil prices has halved revenues, and shortages of foodstuffs and medicines – even petrol – are starting to be felt.

This cash squeeze has triggered a three-way battle for control of what remains of the country’s oil wealth. Much of Libya’s largest group of oil fields, the Sirte Basin, is now held by Islamic State, which has interposed itself between forces of the rival governments. Most of what remains is in eastern Libya, held by the elected parliament based in Tobruk.

Tobruk is using its status as the internationally recognised government to battle in foreign courts for the right to income from other producing fields, opposing the state-owned National Oil Corporation, whose headquarters remains in Tripoli, held by a rival parliament.

Tobruk has set up a second National Oil Corporation, based in eastern Libya, and last month demanded international oil companies switch payments that currently go to Tripoli.

Countering that, Tripoli’s NOC chief, Mustafa Sanallah, convened a conference in London in October calling on oil buyers to stick with him. Two of the world’s largest oil buyers, Glencore and Vitol, have agreed, but the eastern government has vowed legal action.

London courts are likely to be the proving ground for this test of wills, with both governments already gearing up for a precedent-setting high court battle, due early next year, for control of the Libya Investment Authority, the country’s £65bn sovereign wealth fund.

But whoever wins control of what remains of the oil industry may find it a pyrrhic victory. John Hamilton, director of London’s Cross-border Information, says the glut of oil on world markets and turbulence around the few remaining oil ports means Libyan oil has already been “priced out” by many buyers.