Leaving behind a cushy life to go on a whirlwind world cricket tour has so far been a journey of self-discovery and learning. And we are only halfway through

Subash Jayaraman in Cricinfo

October 11, 2014

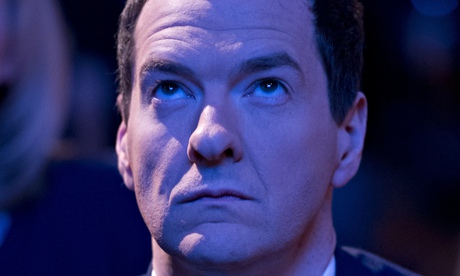

With wife Kathleen and Colin Croft in Trinidad © Subash Jayaraman

It has been nearly three months since my wife Kathleen and I boarded a flight out of Newark International Airport in New Jersey headed for Port-of-Spain, Trinidad & Tobago - the first leg of a cricket journey around the world that is to culminate at the final of the 2015 World Cup in Melbourne, Australia. The objective: 255 days on the road through 12 countries, following as much cricket as we can.

This was a dream trip many years in the making for me as a cricket fan. As such, the decision to leave our cushy lives of comfort and guaranteed salaries to explore the cricket world and come back to start anew wasn't that hard to make. After all, it is cricket we are talking about.

Though I swear by cricket, I actually didn't step inside a cricket stadium to watch an international match until 2007. Growing up in India, cricket was always around me, but I never had the means to actually be at a match. I watched it on TV, read about it in newspapers and magazines, played it in the streets, backyards and terraces, on patches of land and in riverbeds, in hostel corridors and in living rooms, but the fan in me wasn't complete till I watched it in the flesh in Antigua during the 2007 World Cup. And then, I caught the bug.

Since then, I have travelled to Jamaica, Trinidad, England, Bangladesh, India and Australia to watch cricket - sometimes as a fan and other times as a media person. As Kathleen and I took more and more one- and two-week long cricket trips, the idea of a long one around the world began to germinate. We took inspiration from an Australian couple who were backpacking through North America for six months while taking in cricket in the Caribbean.

| Fans went out of their way to help us find accommodation, buy us a few pints, help us with travel and food | |||

As soon as we returned to our home in USA after watching a Test in Trinidad in 2012, we looked up the Future Tours Programme and decided that the 2015 World Cup in Australia and New Zealand was an obvious final destination of our trip. We worked backwards to come up with an itinerary that took us through almost every Test-playing nation, and set off on July 15, 2014. Since we derived our inspiration in Trinidad, it was logical to begin our trip there.

We have met former and current Test cricketers, legends, commentators, famous writers and journalists, who have all enriched the trip in more ways than we could have imagined. More than that, it has been the fans - some friends and some strangers - who went out of their way to help us find accommodation, buy us a few pints, help us with travel and food - who have made this trip possible and thoroughly memorable.

We had the privilege of speaking to Colin Croft about his career and the great West Indian side he was part of, while sitting in the stands of the Queen's Park Oval, the venue of his best bowling figures. We have been within touching of Sir Garfield Sobers at the Kensington Oval. We paid our respects at the final resting places of Sir Frank Worrell and Sir Clyde Walcott. We had the joy of bowling in the Wanderers Cricket Club nets, the oldest club in Barbados. We were given a guided tour of a cricket museum by Malcolm Marshall's son. We sat among the who's who of Indian and English cricket journalists covering the Tests in England. We shared a lunch table with Kapil Dev and Wasim Akram. We rode tubes and elevators with some of the best known voices in the game. We were interviewed on the BBC. We had a feature written about us in an Indian newspaper. We ate dinner in a castle in Ireland that was formerly the summer home of Ranjitsinhji during his last years. We walked into the home of one of the great names in Indian cricket and spent hours talking cricket. We got a private tour of the only cricket museum in India. Many of these instances are each worthy of a piece of its own, and I shall revisit some of them in these pages at a later time.

| |||

Many people have asked us: Why make this trip at all? What are our plans once the trip is over? What is it all for?

Well, it is part fun, part self-discovery, and part experimentation. We were leading lives of comfort and security, where we seemed to be almost on autopilot. Putting our regular lives on hold for nine months to see whether we - a cricket addict and a "cricket widow" - could come out the other side is certainly one aspect of it. It is also an opportunity for Kathleen to explore the cricket world, its culture, customs and traditions to better understand the sport her husband is so hopelessly addicted to.

We do not know just yet what we will do when the trip is over. We moved out of the apartment we lived in for years and gave away nearly all of our possessions. In effect, we have forced ourselves to start afresh. The future is wide open and filled with limitless possibilities.

We are currently winding down the (southern) Indian leg of the trip and are headed to the UAE to watch the Pakistan-Australia Tests. Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, India (the north), South Africa, Zimbabwe, Australia and New Zealand await. About 160 days of travel and cricket are still ahead of us, and based on our experiences so far, they promise to be one hell of a ride. Most of all, we look forward to meeting the people who are bound to keep making this trip unforgettable. As we have learned in our time on the road so far, the cricket world is full of friends; only, we haven't met them all yet.