In 2011, researchers at the University of Chicago conducted a simple experiment to ascertain whether a rat would release another rat from a cage without being given a reward. The answer was yes. After several sessions, the rats learned intentionally and quickly to open the restrainer and release the caged rats. The rats also repeated the behaviour even when they were denied the reward of reunion. Even more astonishing, when the rats were presented with two cages, one containing a rat, the other chocolate, they chose to open both cages and "typically shared the chocolate".

For the researchers, the conclusion was inescapable: the rats were displaying empathy. Announcing the results in

Science, the lead researcher, Peggy Mason, explained: "There is nothing in it except whatever feeling they get from helping another individual."

Neuroscientists are not the only ones to see empathy – or its absence – everywhere these days. According to

Barack Obama, the

"empathy deficit" is a more pressing political problem for America than the federal deficit and holds the key to the success of his second term as he seeks to build bridges with Republicans and tackle the wave of horrific shootings that last year disfigured American communities from Colorado to Connecticut. On this side of the Atlantic, meanwhile, George Osborne's enthusiasm for welfare cuts is explained by the coalition cabinet's

"lack of empathy" for the poor.

But can the solution to violence, cruelty and the divide between liberals and conservatives really be a matter of promoting a trait that we appear to share with rats? And are scientists and politicians talking about the same thing when they invoke empathy in these different experimental and social contexts?

One of the problems with using the same word to describe the pro-social behaviour of rats and similar behaviour observed in humans is that people are infinitely more complex and reflective than rodents. It also confuses the different psychological and philosophical meanings of empathy.

Thus modern-day neuroscientists and social psychologists, drawing on the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher Adam Smith's notion of a "moral sentiment", have come to regard empathy as intrinsically pro-social. When we empathise, they argue, we mirror the distress of an "other" and, unless our brains are damaged or we are developmentally abnormal, we are moved to alleviate their suffering.

The result is that, like other modern moral sentiments such as trust and altruism, empathy is increasingly seen as a "social glue" and the evolutionary basis of human co-operation. But what if this notion reflects nothing more than the current vogue for connectedness that permeates the post-Darwinian sciences and our internet-obsessed times? What if, instead of empathy being the basis of modern social life, it is merely a product of changing scientific fashions?

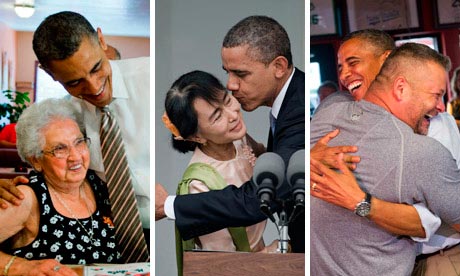

Barack Obama in Boone, North Carolina; at a campaign event in Chicago; and with Rose Mary Sabo-Brown, who received a medal of honour for her late husband, US army specialist Leslie H Sabo, Jr. Photograph: Jewel Samad/Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty

Barack Obama in Boone, North Carolina; at a campaign event in Chicago; and with Rose Mary Sabo-Brown, who received a medal of honour for her late husband, US army specialist Leslie H Sabo, Jr. Photograph: Jewel Samad/Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty

Although empathy has become something of a political buzzword, it is surprisingly difficult to define. Moreover, a survey of the scientific and historical literature reveals that its meaning has shifted significantly over time.

The word first appeared, misspelled as enpathy, in a 1909 lecture by the Cornell psychologist Edward B Titchener, and in a translation credited to the Cambridge philosopher and psychologist James Ward the same year. Inspired by the German aesthetic term Einfühlung, meaning "feeling into", Titchener compared empathy to an enlivening process whereby an art object evoked actual or incipient bodily movements and accompanying emotions in the viewer.

This made it very different from the far older term sympathy, or Victorian notions of the "sympathetic imagination", which novelists such as George Eliot considered a cognitive act in which readers learned to extend themselves into the experiences, motives and emotions of fictional characters.

For empathy to become more like sympathy, it first had to transit from aesthetics to interpersonal

psychology and the new brain sciences. The key shift came in 1992 when a group of

Italian researchers observed neurons in macaque monkeys that fired both when they picked up a raisin and when they saw a person pick up a raisin. A few years later, similar "mirror neurons" were identified in humans.

Since then,

neuroscience has greatly expanded our understanding of the "empathy circuit". The key brain regions appear to be the

amygdala, which is involved in the regulation of emotional learning and the reading of emotional expressions, and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which activates when people experience their own pain or observe others in pain. Another important area is the anterior insula (AI), which lights up in response both to one's own pain and a loved one's pain, as well as to other emotional elicitors, such as disgusting tastes and images.

But perhaps the most important region of all is the medial prefrontal cortex (MPC), also known as the prefrontal lobe. A "hub" for social information processing, the MPC modulates self-awareness and our awareness of other people's thoughts and feelings. It also appears to play an important role in "marking" certain emotional experiences so as to provide us with emotional shortcuts to actions that are positive and therefore likely to be rewarding.

The neuroscientists Antonio and Hanna Damasio

have shown that patients with damage to the ventromedial part of the MPC – the section closely associated with self-awareness – typically have great trouble learning from previous emotional experiences or making decisions, seeing equal merit in every course of action. Such patients also show less of a change in their heartbeat and other autonomic responses when shown distressing images. In this respect, their response mirrors that of sociopaths who may have suffered no medical trauma.

For some writers, these discoveries show that empathy is hard-wired and that we are primed for morality, hence the writer Jeremy Rifkin's

claim that these circuits are the source of humanity's desire for "intimate participation and companionship".

However, as

Simon Baron-Cohen, an expert on autism spectrum disorders, has shown, this is frequently not the case. Psychopaths, for instance, tend to be very good at reading other people's emotions while remaining emotionally unmoved themselves. Adolescents with a history of violence and diagnoses of "conduct disorder" exhibit similar traits.

By contrast, people with autism and Asperger's syndrome are very poor at reading non-verbal emotional signals and other social clues, but, once they become aware of how others are feeling, they are capable of sharing those emotions intensely. The result is that, while both psychopaths and people with Asperger's could both be characterised as having "zero degrees of empathy, only psychopaths are capable of extreme cruelty.

Where Baron-Cohen and others run into difficulty is in accounting for emotions such as schadenfreude. Far from being a form of counter-empathy, schadenfreude appears to involve empathically mirroring another person's distress and taking pleasure in that distress at the same time. Indeed, in role-playing games involving "altruistic punishment", brain researchers have found that both the ACC and the dorsal striatum – the brain's pleasure/reward centre – are activated.

Neuroscientific approaches also tend to give too little weight to the cognitive dimensions of empathy. A horrific illustration of this was the cold-blooded shooting of 69 Norwegian Labour activists by

Anders Behring Breivik in 2011. At his trial, Breivik argued that he was fully capable of empathy but had used a "meditation technique" to override his feelings. "If you are going to be capable of executing such a bloody and horrendous operation you need to work on your mind, your psyche, for years," he explained.

As the German historian of emotions Ute Frevert puts it: "The fact that human beings are naturally equipped to feel what others feel does not mean that they always do so. They might just turn away and act indifferent."

So how can we make it less likely that people such as Breivik or Adam Lanza, the 20-year-old responsible for the horrific

shooting in December in Newtown, Connecticut, commit acts of mass murder in future?

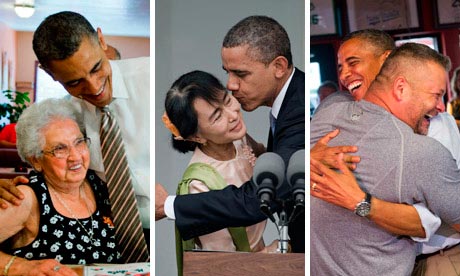

Barack Obama at a cafe in Pueblo, Colorado; with Aung San Suu Kyi at her residence in Yangon; and with Scott Van Duzer, owner of Big Apple Pizza in Florida. Photograph: Jim Watson/Nicolas Asfouri/Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images

Barack Obama at a cafe in Pueblo, Colorado; with Aung San Suu Kyi at her residence in Yangon; and with Scott Van Duzer, owner of Big Apple Pizza in Florida. Photograph: Jim Watson/Nicolas Asfouri/Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images

The most common answer is by fostering greater perspective-taking. Decades of scientific research show that people are kinder to those they view as human beings. The reason is that, when we make the imaginative effort to step into the shoes of another person and see things from their perspective, we become less capable of ignoring their suffering. Indeed,

brain imaging studies of Buddhists who use meditation exercises to contemplate compassion on a daily basis show increased activation of the amygdala and other parts of the brain's empathy circuit.

Novels, television and the internet can also foster greater empathy by exposing us to the perspectives of people whose lives we would not otherwise consider. This is particularly the case when empathy is married with "humanitarian reason" – the force that Harvard psychologist

Steven Pinker credits for the steady decline in levels of societal violence since the Enlightenment.

However, as the response last year to Invisible Children's

video about the Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony showed, this sort of empathy can be short-lived. Yes, nearly 100 million people shared Invisible Children's video on YouTube, but the outcry against Kony was temporary and people quickly found new objects for their indignation.

Moreover, far from being a guide to what is right, empathy often leads us astray, as when judges go easier on white-collar criminals who share their social background, which is why we frequently invoke other values and principles to balance such tendencies. This is precisely the argument made by Jonathan Haidt in his book

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Haidt maintains that empathy, or what he labels the "harm/care" module, is just one of several emotional dispositions that undergird our moral outlook, the others being fairness, liberty, loyalty, authority and purity/sanctity. The difference between Democrats and Republicans is that, while liberals focus almost entirely on care and fairness, conservatives tend to give equal weight to all six dispositions.

In theory, this should be good news for Osborne as he seeks to counter perceptions that his austerity measures are "uncaring", and even better news for Republicans, especially as something like 42% of the American electorate self-identify as conservative. However, as

Obama's response to Mitt Romney's

unfortunate remarks about the "47%" underlined, the perceived absence of empathy is a powerful weapon with which to browbeat a political opponent. Perhaps this is why, rather than defending his comments about the 47% on traditional conservative grounds, Romney spent the closing weeks of last year's campaign desperately trying to persuade voters that he was just as compassionate as Obama.

Even before hurricane Sandy upset the candidates' campaign plans, however, that was not an argument that carried much weight with the undecideds and, following the pictures of

Obama embracing the victims of the storm damage in New Jersey, it was pretty much game, set and match to the incumbent.

Indeed, if there is a lesson to be drawn from the 2012 presidential election, it is that empathy is here to stay and that where candidates once talked about "the economy, stupid" they would now be well-advised to use a different E-word.

Empathy is not the only "moral emotion" that is enjoying a renaissance thanks to social neuroscience. Scientists have also been probing the biological processes involved in trust and altruism.

One theory is that when we empathise oxytocin and other chemicals flood the brain's pleasure centres, resulting in a "warm glow" effect. Similar surges occur when people are asked to play economic exchange games designed to elicit trust.

According to neuroeconomists such as Paul Zak, this suggests that empathy and trust are two sides of the same adaptive response – the idea being that our brains have evolved so that it literally feels good to empathise and to trust people.

Primatologists such as Frans de Waal believe that altruism may be the result of similar selection pressures. Spontaneous assistance has long been observed in apes, hence the adoption of orphans by wild male chimpanzees who may devote years of costly care to unrelated juveniles. And, as the Chicago experiment illustrates, rats also exhibit similar altruistic behaviour without their altruism being repaid.

In the case of humans, altruism is more complicated as over the course of a lifetime we will co-operate with thousands of genetically unrelated strangers with whom we are unlikely to interact again. In such societies, the advantages of forming a good reputation are minimal. At the same time, it is easy for unscrupulous individuals, known as "free-riders", to exploit the "trusting" instincts of the majority.

To explains this, neuroeconomists posit that a unique form of co-operation has evolved in human societies in which social norms are learned, co-operators are altruistically rewarded and free-riders are altruistically punished.

This theory is supported by studies of economic role-playing games in which punishment is used to motivate two players to co-operate and a failure to show and reciprocate altruism leaves both players worse off.

However, such games also pose a problem for the notion that humans are hard-wired for pro-sociality and morality as brain scans of altruisitic punishers show that they both empathise with the free-rider and take an active pleasure in his or her punishment. In other words, as anyone who has experienced schadenfreude knows, sometimes it feels good to act cruelly.