Maya Jasanoff in The Guardian

A terrorist bombing in London, a shipping accident in southeast Asia, political unrest in a South American republic and mass violence in central Africa: each of these topics has made headlines in the past few months. But these “news” stories have also been in circulation for more than a century, as plotlines in the novels of Joseph Conrad, one of the greatest and most controversial modern English writers.

Conrad is known to most readers as the author of Heart of Darkness, about a British sea captain’s journey up an unnamed African river. And Heart of Darknessis known to many as the object of a blistering critique by the late Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, who condemned Conrad as “a bloody racist” for his degrading portrayal of Africans. It is right to call out the racism – and, for that matter, the orientalism, antisemitism and androcentrism – in Conrad’s work. But his dated prejudices, abhorrent though they are to readers today, coexist in his work with elements of exceptional clairvoyance.

The 100 best novels: No 32 – Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (1899)

Today, more than ever, Conrad demands our attention for his insight into the moral challenges of a globalised world. In an age of Islamist terrorism, it is striking to note that the same author who condemned imperialism in Heart of Darkness(1899) also wrote The Secret Agent (1907), which centres around a conspiracy of foreign terrorists in London. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, it is uncanny to read Conrad in Nostromo (1904) portraying multinational capitalism as a maker and breaker of states. As the digital revolution gathers momentum, one finds Conrad writing movingly, in Lord Jim (1900) and many other works set at sea, about the consequences of technological disruption. As debates about immigration unsettle Europe and the US, one can only marvel afresh at how Conrad produced any of these books in English – his third language, which he learned only as an adult.

Conrad was born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski in 1857 to Polish nationalist parents in the Russian empire. He came of age in the shadow of imperial oppression; his parents were exiled for political activism. Both of them died under the stress, leaving Conrad an orphan at 11. For the rest of his life, he carried the scars of a youth traumatised by punishing authoritarianism, as well as what he considered a fatal, useless idealism.

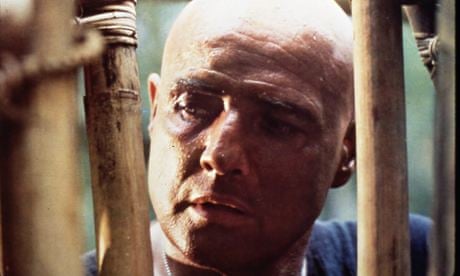

John Malkovich and Iman in the 1993 film adaptation of Heart of Darkness. The book has been criticised for its degrading portrayal of Africans. Photograph: Allstar

He travelled to France aged 16 to train as a sailor. For the next 20 years, he worked as a professional mariner, sailing to the Caribbean, Africa, southeast Asia and Australia. From the deck of a ship, he witnessed a transformation in the intensity of global interconnections. Conrad docked alongside oceangoing steamers that transported immigrants from Europe and Asia on a scale never seen before or since. He cruised over the transoceanic telegraph cables that moved news, for the first time in history, faster than people. Between voyages, he made his home in London, the centre of a global financial market that was more integrated during his lifetime than it would be again until the 1980s.

Based in England from 1878, Conrad learned English from scratch, became a proud naturalised British citizen and moved up the ranks of the merchant marine – an all-round immigrant success story. But he also witnessed the rise of xenophobia and nativism. A string of anarchist bombings and assassinations on the continent stoked suspicions of young foreign men – even though what terrorist bombings there were in 1880s Britain were committed by Fenians. Paranoia about anarchism, combined with antisemitism and fears about immigrants stealing British jobs, led to the passing of the 1905 Aliens Act, the first peacetime immigration restriction in British history.

By then, Conrad had left the sea and become a published author and a married father, living in Kent. He channelled his international perspective into a body of writing based overwhelmingly on personal experience and real incidents. A map of Conrad’s fiction looks strikingly different from that of his contemporary Rudyard Kipling, the informal poet laureate of the British empire. Conrad roamed across Asia, Africa, Europe and South America without setting a single novel in a British colony. Although he was a fervent British patriot – he believed that, of all the empires, Britain’s was the best – Conrad was acutely aware of the limits of British power. Nostromo predicts American ascendancy with chilling clarity. In the novel, a San Francisco mining magnate declares: “We shall run the world’s business whether the world likes it or not.”

By then, Conrad had left the sea and become a published author and a married father, living in Kent. He channelled his international perspective into a body of writing based overwhelmingly on personal experience and real incidents. A map of Conrad’s fiction looks strikingly different from that of his contemporary Rudyard Kipling, the informal poet laureate of the British empire. Conrad roamed across Asia, Africa, Europe and South America without setting a single novel in a British colony. Although he was a fervent British patriot – he believed that, of all the empires, Britain’s was the best – Conrad was acutely aware of the limits of British power. Nostromo predicts American ascendancy with chilling clarity. In the novel, a San Francisco mining magnate declares: “We shall run the world’s business whether the world likes it or not.”

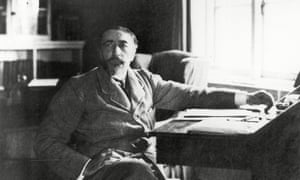

‘It almost seems as if he wrote his fiction through a zoom lens pointed at the future’... Joseph Conrad. Photograph: Granger/REX/Shutterstock

Across his writing, Conrad grappled with the ethical ramifications of living in a globalised world: the effects of dislocation, the tension and opportunity of multiethnic societies, the disruption wrought by technological change. He understood acutely the way that individuals move within systems larger than themselves, that even the freest will can be constrained by what he would have called fate. Conrad’s moral universe revolved around a critique of the European notion of civilisation, which for Conrad generally spelled selfishness and greed in place of honour and a sense of the greater good. He mocks its bourgeois pieties in The Secret Agent; in Heart of Darkness, he tears off its hypocritical mask. In Lord Jim, he offers a compelling portrait of a flawed person stumbling to chart an honourable course when the world’s moral compass has lost its poles.

Conrad, a lifelong depressive, excelled at the art of the unhappy ending. Yet the essential ethical question of his work – how can one do good in a bad world? – transcends any character or plot. His novels stand as invitations for readers to seek happier answers for themselves.

While the British empire is gone and Kipling’s relevance has receded, Conrad’s realms shimmer beneath the surface of our own. Internet cables run along the sea floor beside the old telegraph wires. Conrad’s characters whisper in the ears of new generations of antiglobalisation protesters and champions of free trade, liberal interventionists and radical terrorists, social justice activists and xenophobic nativists. Ninety per cent of world trade travels by sea, which makes ships and sailors more important to the world economy than ever before.

Conrad brought to all his work the sensibility of a “homo duplex”, as he once called himself – a man of multiple identities. This gives his fiction a particular power for those of us trying to reconcile competing scales of value and beliefs. That Conrad failed to measure up to our moral standards of racial tolerance is a humbling reminder of how our own practices might be judged wanting in future.

It is especially poignant to read Conrad in the context of a post-Brexit Britain. One of Conrad’s most moving short stories, “Amy Foster”, describes the fate of an eastern European man named Yanko, who is shipwrecked on the shores of Kent. In the rural community into which he stumbles, he is rejected as an outlandish stranger by everyone except Amy, a simple farm girl. They fall in love, get married and have a baby boy – but when Yanko cradles his son with an eastern lullaby, his wife snatches the infant away. He falls ill, slips into his native language and dies of a broken heart. “His foreignness had a peculiar and indelible stamp,” wrote Conrad. “At last people became used to see him. But they never became used to him.”

In Lowestoft, where Conrad landed in Britain in 1878, there is a pub opposite the railway station called the Joseph Conrad – which is fitting, since Conrad recalled learning English by poring over newspapers in Lowestoft pubs. He would have been astonished to learn that Poles are now by far the largest foreign-born population in Britain. But Lowestoft voted heavily for Brexit and the Joseph Conrad is part of the pub chain JD Wetherspoon, whose chairman, Tim Martin, was a staunch supporter of leave. One can only wonder what reception a freshly arrived Konrad Korzeniowski would get there today.