'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label heart. Show all posts

Showing posts with label heart. Show all posts

Tuesday, 12 April 2022

Sunday, 29 October 2017

How Joseph Conrad foresaw the dark heart of Brexit Britain

From financial crises to the threat of terrorism, the works of the Polish-British author display remarkable insight into an era, like ours, of elemental change in a globalised world

Maya Jasanoff in The Guardian

A terrorist bombing in London, a shipping accident in southeast Asia, political unrest in a South American republic and mass violence in central Africa: each of these topics has made headlines in the past few months. But these “news” stories have also been in circulation for more than a century, as plotlines in the novels of Joseph Conrad, one of the greatest and most controversial modern English writers.

Conrad is known to most readers as the author of Heart of Darkness, about a British sea captain’s journey up an unnamed African river. And Heart of Darknessis known to many as the object of a blistering critique by the late Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, who condemned Conrad as “a bloody racist” for his degrading portrayal of Africans. It is right to call out the racism – and, for that matter, the orientalism, antisemitism and androcentrism – in Conrad’s work. But his dated prejudices, abhorrent though they are to readers today, coexist in his work with elements of exceptional clairvoyance.

The 100 best novels: No 32 – Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (1899)

Today, more than ever, Conrad demands our attention for his insight into the moral challenges of a globalised world. In an age of Islamist terrorism, it is striking to note that the same author who condemned imperialism in Heart of Darkness(1899) also wrote The Secret Agent (1907), which centres around a conspiracy of foreign terrorists in London. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, it is uncanny to read Conrad in Nostromo (1904) portraying multinational capitalism as a maker and breaker of states. As the digital revolution gathers momentum, one finds Conrad writing movingly, in Lord Jim (1900) and many other works set at sea, about the consequences of technological disruption. As debates about immigration unsettle Europe and the US, one can only marvel afresh at how Conrad produced any of these books in English – his third language, which he learned only as an adult.

Conrad was born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski in 1857 to Polish nationalist parents in the Russian empire. He came of age in the shadow of imperial oppression; his parents were exiled for political activism. Both of them died under the stress, leaving Conrad an orphan at 11. For the rest of his life, he carried the scars of a youth traumatised by punishing authoritarianism, as well as what he considered a fatal, useless idealism.

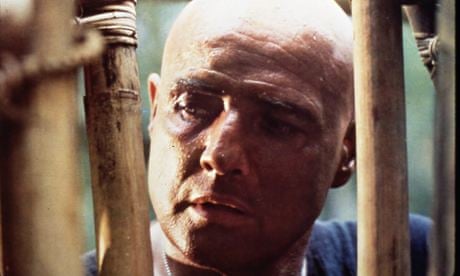

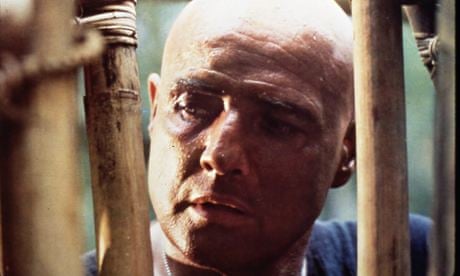

John Malkovich and Iman in the 1993 film adaptation of Heart of Darkness. The book has been criticised for its degrading portrayal of Africans. Photograph: Allstar

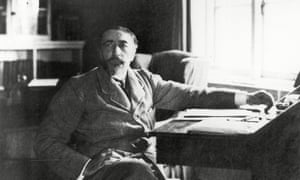

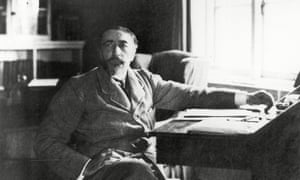

‘It almost seems as if he wrote his fiction through a zoom lens pointed at the future’... Joseph Conrad. Photograph: Granger/REX/Shutterstock

Across his writing, Conrad grappled with the ethical ramifications of living in a globalised world: the effects of dislocation, the tension and opportunity of multiethnic societies, the disruption wrought by technological change. He understood acutely the way that individuals move within systems larger than themselves, that even the freest will can be constrained by what he would have called fate. Conrad’s moral universe revolved around a critique of the European notion of civilisation, which for Conrad generally spelled selfishness and greed in place of honour and a sense of the greater good. He mocks its bourgeois pieties in The Secret Agent; in Heart of Darkness, he tears off its hypocritical mask. In Lord Jim, he offers a compelling portrait of a flawed person stumbling to chart an honourable course when the world’s moral compass has lost its poles.

Conrad, a lifelong depressive, excelled at the art of the unhappy ending. Yet the essential ethical question of his work – how can one do good in a bad world? – transcends any character or plot. His novels stand as invitations for readers to seek happier answers for themselves.

While the British empire is gone and Kipling’s relevance has receded, Conrad’s realms shimmer beneath the surface of our own. Internet cables run along the sea floor beside the old telegraph wires. Conrad’s characters whisper in the ears of new generations of antiglobalisation protesters and champions of free trade, liberal interventionists and radical terrorists, social justice activists and xenophobic nativists. Ninety per cent of world trade travels by sea, which makes ships and sailors more important to the world economy than ever before.

Conrad brought to all his work the sensibility of a “homo duplex”, as he once called himself – a man of multiple identities. This gives his fiction a particular power for those of us trying to reconcile competing scales of value and beliefs. That Conrad failed to measure up to our moral standards of racial tolerance is a humbling reminder of how our own practices might be judged wanting in future.

It is especially poignant to read Conrad in the context of a post-Brexit Britain. One of Conrad’s most moving short stories, “Amy Foster”, describes the fate of an eastern European man named Yanko, who is shipwrecked on the shores of Kent. In the rural community into which he stumbles, he is rejected as an outlandish stranger by everyone except Amy, a simple farm girl. They fall in love, get married and have a baby boy – but when Yanko cradles his son with an eastern lullaby, his wife snatches the infant away. He falls ill, slips into his native language and dies of a broken heart. “His foreignness had a peculiar and indelible stamp,” wrote Conrad. “At last people became used to see him. But they never became used to him.”

In Lowestoft, where Conrad landed in Britain in 1878, there is a pub opposite the railway station called the Joseph Conrad – which is fitting, since Conrad recalled learning English by poring over newspapers in Lowestoft pubs. He would have been astonished to learn that Poles are now by far the largest foreign-born population in Britain. But Lowestoft voted heavily for Brexit and the Joseph Conrad is part of the pub chain JD Wetherspoon, whose chairman, Tim Martin, was a staunch supporter of leave. One can only wonder what reception a freshly arrived Konrad Korzeniowski would get there today.

Maya Jasanoff in The Guardian

A terrorist bombing in London, a shipping accident in southeast Asia, political unrest in a South American republic and mass violence in central Africa: each of these topics has made headlines in the past few months. But these “news” stories have also been in circulation for more than a century, as plotlines in the novels of Joseph Conrad, one of the greatest and most controversial modern English writers.

Conrad is known to most readers as the author of Heart of Darkness, about a British sea captain’s journey up an unnamed African river. And Heart of Darknessis known to many as the object of a blistering critique by the late Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe, who condemned Conrad as “a bloody racist” for his degrading portrayal of Africans. It is right to call out the racism – and, for that matter, the orientalism, antisemitism and androcentrism – in Conrad’s work. But his dated prejudices, abhorrent though they are to readers today, coexist in his work with elements of exceptional clairvoyance.

The 100 best novels: No 32 – Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (1899)

Today, more than ever, Conrad demands our attention for his insight into the moral challenges of a globalised world. In an age of Islamist terrorism, it is striking to note that the same author who condemned imperialism in Heart of Darkness(1899) also wrote The Secret Agent (1907), which centres around a conspiracy of foreign terrorists in London. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, it is uncanny to read Conrad in Nostromo (1904) portraying multinational capitalism as a maker and breaker of states. As the digital revolution gathers momentum, one finds Conrad writing movingly, in Lord Jim (1900) and many other works set at sea, about the consequences of technological disruption. As debates about immigration unsettle Europe and the US, one can only marvel afresh at how Conrad produced any of these books in English – his third language, which he learned only as an adult.

Conrad was born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski in 1857 to Polish nationalist parents in the Russian empire. He came of age in the shadow of imperial oppression; his parents were exiled for political activism. Both of them died under the stress, leaving Conrad an orphan at 11. For the rest of his life, he carried the scars of a youth traumatised by punishing authoritarianism, as well as what he considered a fatal, useless idealism.

John Malkovich and Iman in the 1993 film adaptation of Heart of Darkness. The book has been criticised for its degrading portrayal of Africans. Photograph: Allstar

He travelled to France aged 16 to train as a sailor. For the next 20 years, he worked as a professional mariner, sailing to the Caribbean, Africa, southeast Asia and Australia. From the deck of a ship, he witnessed a transformation in the intensity of global interconnections. Conrad docked alongside oceangoing steamers that transported immigrants from Europe and Asia on a scale never seen before or since. He cruised over the transoceanic telegraph cables that moved news, for the first time in history, faster than people. Between voyages, he made his home in London, the centre of a global financial market that was more integrated during his lifetime than it would be again until the 1980s.

Based in England from 1878, Conrad learned English from scratch, became a proud naturalised British citizen and moved up the ranks of the merchant marine – an all-round immigrant success story. But he also witnessed the rise of xenophobia and nativism. A string of anarchist bombings and assassinations on the continent stoked suspicions of young foreign men – even though what terrorist bombings there were in 1880s Britain were committed by Fenians. Paranoia about anarchism, combined with antisemitism and fears about immigrants stealing British jobs, led to the passing of the 1905 Aliens Act, the first peacetime immigration restriction in British history.

By then, Conrad had left the sea and become a published author and a married father, living in Kent. He channelled his international perspective into a body of writing based overwhelmingly on personal experience and real incidents. A map of Conrad’s fiction looks strikingly different from that of his contemporary Rudyard Kipling, the informal poet laureate of the British empire. Conrad roamed across Asia, Africa, Europe and South America without setting a single novel in a British colony. Although he was a fervent British patriot – he believed that, of all the empires, Britain’s was the best – Conrad was acutely aware of the limits of British power. Nostromo predicts American ascendancy with chilling clarity. In the novel, a San Francisco mining magnate declares: “We shall run the world’s business whether the world likes it or not.”

By then, Conrad had left the sea and become a published author and a married father, living in Kent. He channelled his international perspective into a body of writing based overwhelmingly on personal experience and real incidents. A map of Conrad’s fiction looks strikingly different from that of his contemporary Rudyard Kipling, the informal poet laureate of the British empire. Conrad roamed across Asia, Africa, Europe and South America without setting a single novel in a British colony. Although he was a fervent British patriot – he believed that, of all the empires, Britain’s was the best – Conrad was acutely aware of the limits of British power. Nostromo predicts American ascendancy with chilling clarity. In the novel, a San Francisco mining magnate declares: “We shall run the world’s business whether the world likes it or not.”

‘It almost seems as if he wrote his fiction through a zoom lens pointed at the future’... Joseph Conrad. Photograph: Granger/REX/Shutterstock

Across his writing, Conrad grappled with the ethical ramifications of living in a globalised world: the effects of dislocation, the tension and opportunity of multiethnic societies, the disruption wrought by technological change. He understood acutely the way that individuals move within systems larger than themselves, that even the freest will can be constrained by what he would have called fate. Conrad’s moral universe revolved around a critique of the European notion of civilisation, which for Conrad generally spelled selfishness and greed in place of honour and a sense of the greater good. He mocks its bourgeois pieties in The Secret Agent; in Heart of Darkness, he tears off its hypocritical mask. In Lord Jim, he offers a compelling portrait of a flawed person stumbling to chart an honourable course when the world’s moral compass has lost its poles.

Conrad, a lifelong depressive, excelled at the art of the unhappy ending. Yet the essential ethical question of his work – how can one do good in a bad world? – transcends any character or plot. His novels stand as invitations for readers to seek happier answers for themselves.

While the British empire is gone and Kipling’s relevance has receded, Conrad’s realms shimmer beneath the surface of our own. Internet cables run along the sea floor beside the old telegraph wires. Conrad’s characters whisper in the ears of new generations of antiglobalisation protesters and champions of free trade, liberal interventionists and radical terrorists, social justice activists and xenophobic nativists. Ninety per cent of world trade travels by sea, which makes ships and sailors more important to the world economy than ever before.

Conrad brought to all his work the sensibility of a “homo duplex”, as he once called himself – a man of multiple identities. This gives his fiction a particular power for those of us trying to reconcile competing scales of value and beliefs. That Conrad failed to measure up to our moral standards of racial tolerance is a humbling reminder of how our own practices might be judged wanting in future.

It is especially poignant to read Conrad in the context of a post-Brexit Britain. One of Conrad’s most moving short stories, “Amy Foster”, describes the fate of an eastern European man named Yanko, who is shipwrecked on the shores of Kent. In the rural community into which he stumbles, he is rejected as an outlandish stranger by everyone except Amy, a simple farm girl. They fall in love, get married and have a baby boy – but when Yanko cradles his son with an eastern lullaby, his wife snatches the infant away. He falls ill, slips into his native language and dies of a broken heart. “His foreignness had a peculiar and indelible stamp,” wrote Conrad. “At last people became used to see him. But they never became used to him.”

In Lowestoft, where Conrad landed in Britain in 1878, there is a pub opposite the railway station called the Joseph Conrad – which is fitting, since Conrad recalled learning English by poring over newspapers in Lowestoft pubs. He would have been astonished to learn that Poles are now by far the largest foreign-born population in Britain. But Lowestoft voted heavily for Brexit and the Joseph Conrad is part of the pub chain JD Wetherspoon, whose chairman, Tim Martin, was a staunch supporter of leave. One can only wonder what reception a freshly arrived Konrad Korzeniowski would get there today.

Friday, 4 July 2014

Murali Kartik: How to bowl spin in England

Murali Kartik in Cricinfo

It was my first match for Middlesex and the team's first of the 2007 Championship. We were playing in Taunton against Justin Langer's Somerset. Ed Smith and Richard Pybus, the Middlesex captain and coach, had told me that I would be only filling in for our four seamers with the odd few overs before lunch, tea, and towards the end of the day.

Middlesex had scored 600 for 4 in their first innings. Left-arm spinner Ian Blackwell had taken one wicket. When it was our turn to bowl, Marcus Trescothick smashed our fast bowlers and Somerset racked up 100 for 1 in about ten overs.

Off my first ball I had Trescothick caught bat-pad at short leg. The guy who was told he would bowl only ten overs in the day ended up bowling 50 and finishing with 4 for 168. The seamers picked up six wickets in the drawn match in which more than 1600 runs had been scored.

You need to be big-hearted to bowl in England. It always boils down to your skill and your heart. That is the lesson I learned in my nine years of county cricket, where I played for four different teams.

India will know that since England don't have a specialist spinner anymore - after Graeme Swann's retirement and the disciplinary issues Monty Panesar is struggling with - it's highly unlikely that they will prepare pitches that will spin big even on the fourth day.

So apart from your batsmen putting up enough runs on the board to let you go out and bowl with confidence, the key to succeeding and remaining consistent as a spinner is to not be attacking all the time. I read that R Ashwin said he would like to be a more attacking spinner. That's easier said than done, especially in England, and given the way Alastair Cook and his men played spin in India in the 2012-13 Test series.

| One of my ploys was to push a fielder deep into areas where I expected the batsman to hit. I was telling the batsman: I'm attacking you, so try and take me on | |||

In first-class cricket in England you need to understand your role on the first few days. If the pitch is not doing much, you become the stock bowler, play with your flight, set in-out fields, depending on the batsman, and give control to the captain and the team.

The conditions also dictate how you bowl. In England it's important to pitch on the right length; for a spinner that is good length. It is a good defensive and attacking length to stick to, particularly on pitches that can be slow. In overseas series, I have seen Ashwin being cut and pulled a lot. You can't lose your lengths in England; you can, at times, play with your lines.

Another important element to bowling well in England is to put a lot of body behind the ball. As Sanjay Manjrekar has repeatedly pointed out, many Indian spinners use their shoulders and fingers to impart turn, which is why they don't get enough out of unresponsive pitches, unlike Australia's Nathan Lyon, who can generate bounce even on pitches that do not take turn because he uses his body a lot more.

During India's first tour match of the 2011 tour to England, against Somerset, Amit Mishra went for some runs despite having bowled well on the second day. When he asked me how I bowled on such pitches, I told him that he had to realise that spinners will be hit. So you need to play around with the batsman's mind and the field placements.

One of my ploys was to push a fielder deep into areas where I expected the batsman to hit. I would place a deep midwicket to Trescothick, who played the lap shot really well and frequently. People might say it is a defensive mindset but they should understand that I am trying to block the batsman's big shot.

You should not be reacting after a shot has been hit. Instead I was telling the batsman: I'm attacking you. I have close-in fielders but I am also placing a fielder here for the big shot, so try and take me on. Sometimes it plays with his ego but it also brings me comfort and gives me freedom to experiment.

In England it is also a question of mind over matter. It is about sticking to your strengths and doing your job. You know the weather can be cold. You know that sometimes the pitches are going to be really slow and might not take spin. When nothing is going well for you, and this happens to every bowler, you must stay positive and bowl well.

It is not always about thinking of wickets. It is about biding your time. You have to adopt a role: if it is cold, keep lots of hand warmers with you; if the pitch is not taking spin, tell yourself you are going to stick to your lengths; play around with the fields; play with the batsman's mind; stick to your strengths.

Indian seamers won't find it hard to get used to the Dukes ball in England since it's similar to the SG ball they bowl with at home © Getty Images

John Emburey, the former Middlesex and England offspinner, told me that it was always good to try things. He said that at Lord's, spinners, especially left-arm ones, usually bowl from the Nursery End to take advantage of the slope. Emburey, who was accustomed to bowling from the Pavilion End, would switch sides with former England left-arm spinner Phil Edmonds to bowl from the Nursery End and bowl tighter lines on the off stump to force the outside edge. So it is important to be aware and open to doing things that you will not generally do.

One advantage the Indian spinners have is, they will not find it hard to get used to the Dukes ball, because it is similar to the one they use at home, the SG Test ball, which has a pronounced seam. The Dukes ball stays hard throughout, which is a good thing for a spinner, especially on a dry surface.

At times, more than the pitches, it is the success of the seamers up front that plays a vital role in the spinner being effective. Some of the surfaces in England can be really slow, especially at Lord's and The Oval. There is nothing for spinners at Trent Bridge. The Old Trafford pitch can break up, but at the Rose Bowl it won't.

Overall, the pitches are not going to be conducive to spin, especially in the wake of England's series defeat against Sri Lanka.

Wednesday, 4 April 2012

How Big Pharma Cooks Data –The Case of Vioxx and Heart Disease

By Cathy O’Neil, a data scientist who lives in New York City and writes at mathbabe.org

Yesterday I caught a lecture at Columbia given by statistics professor David Madigan, who explained to us the story of Vioxx and Merck. It’s fascinating and I was lucky to get permission to retell it here.

Disclosure

Madigan has been a paid consultant to work on litigation against Merck. He doesn’t consider Merck to be an evil company by any means, and says it does lots of good by producing medicines for people. According to him, the following Vioxx story is “a line of work where they went astray”.

Yet Madigan’s own data strongly suggests that Merck was well aware of the fatalities resulting from Vioxx, a blockbuster drug that earned them $2.4b in 2003, the year before it “voluntarily” pulled it from the market in September 2004. What you will read below shows that the company set up standard data protection and analysis plans which they later either revoked or didn’t follow through with, they gave the FDA misleading statistics to trick them into thinking the drug was safe, and set up a biased filter on an Alzheimer’s patient study to make the results look better. They hoodwinked the FDA and the New England Journal of Medicine and took advantage of the public trust which ultimately caused the deaths of thousands of people.

The data for this talk came from published papers, internal Merck documents that he saw through the litigation process, FDA documents, and SAS files with primary data coming from Merck’s clinical trials. So not all of the numbers I will state below can be corroborated, unfortunately, due to the fact that this data is not all publicly available. This is particularly outrageous considering the repercussions that this data represents to the public.

Background

The process for getting a drug approved is lengthy, requires three phases of clinical trials before getting FDA approval, and often takes well over a decade. Before the FDA approved Vioxx, less than 20,000 people tried the drug, versus 20,000,000 people after it was approved. Therefore it’s natural that rare side effects are harder to see beforehand. Also, it should be kept in mind that for the sake of clinical trials, they choose only people who are healthy outside of the one disease which is under treatment by the drug, and moreover they only take that one drug, in carefully monitored doses. Compare this to after the drug is on the market, where people could be unhealthy in various ways and could be taking other drugs or too much of this drug.

Vioxx was supposed to be a new “NSAID” drug without the bad side effects. NSAID drugs are pain killers like Aleve and ibuprofen and aspirin, but those had the unfortunate side effects of gastro-intestinal problems (but those are only among a subset of long term users, such as people who take painkillers daily to treat chronic pain, such as people with advanced arthritis). The goal was to find a pain-killer without the GI side effects. The underlying scientific goal was to find a COX-2 inhibitor without the COX-1 inhibition, since scientists had realized in 1991 that COX-2 suppression corresponded to pain relief whereas COX-1 suppression corresponded to GI problems.

Vioxx Introduced and Withdrawn From the Market

The timeline for Vioxx’s introduction to the market was accelerated: they started work in 1991 and got approval in 1999. They pulled Vioxx from the market in 2004 in the “best interest of the patient”. It turned out that it caused heart attacks and strokes. The stock price of Merck plummeted and $30 billion of its market cap was lost. There was also an avalanche of lawsuits, one of the largest resulting in a $5 billion settlement which was essentially a victory for Merck, considering they made a profit of $10 billion on the drug while it was being sold.

The story Merck will tell you is that they “voluntarily withdrew” the drug on September 30, 2004. In a placebo-controlled study of colon polyps in 2004, it was revealed that over a time period of 1200 days, 4% of the Vioxx users suffered a “cardiac, vascular, or thoracic event” (CVT event), which basically means something like a heart attack or stroke, whereas only 2% of the placebo group suffered such an event. In a group of about 2400 people, this was statistically significant, and Merck had no choice but to pull their drug from the market.

It should be noted that, on the one hand Merck should be applauded for checking for CVT events on a colon polyps study, but on the other hand that in 1997, at the International Consensus Meeting on COX-2 Inhibition, a group of leading scientists issued a warning in their Executive Summary that it was “… important to monitor cardiac side effects with selective COX-2 inhibitors”. Moreover, in an internal Merck email as early as 1996, it was stated there was a “… substantial chance that CVT will be observed.” In other words, Merck knew to look out for such things. Importantly, however, there was no subsequent insert in the medicine’s packaging that warned of possible CVT side-effects.

What the CEO of Merck Said

What did Merck say to the world at that point in 2004? You can look for yourself at the four and half hour Congressional hearing (seen on C-SPAN) which took place on November 18, 2004. Starting at 3:27:10, the then-CEO of Merck, Raymond Gilmartin, testifies that Merck “puts patients first” and “acted quickly” when there was reason to believe that Vioxx was causing CVT events. Gilmartin also went on the Charlie Rose show and repeated these claims, even go so far as stating that the 2004 study was the first time they had a study which showed evidence of such side effects.

How quickly did they really act though? Were there warning signs before September 30, 2004?

Arthritis Studies

Let’s go back to the time in 1999 when Vioxx was FDA approved. In spite of the fact that it was approved for a rather narrow use, mainly for arthritis sufferers who needed chronic pain management and were having GI problems on other meds (keeping in mind that Vioxx was way more expensive than ibuprofen or aspirin, so why would you use it unless you needed to), Merck nevertheless launched an ad campaign with Dorothy Hamill and spent $160m (compare that with Budweiser which spent $146m or Pepsi which spent $125m in the same time period).

As I mentioned, Vioxx was approved faster than usual. At the time of its approval, the completed clinical studies had only been 6- or 12-week studies; no longer term studies had been completed. However, there was one underway at the time of approval, namely a study which compared Aleve with Vioxx for people suffering from osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

What did the arthritis studies show? These results, which were available in late 2003, showed that the CVT events were more than twice as likely with Vioxx as with Aleve (CVT event rates of 32/1304 = 0.0245 with Vioxx, 6/692 = 0.0086 with Aleve, with a p-value of 0.01). As we see this is a direct refutation of the fact that CEO Gilmartin stated that they didn’t have evidence until 2004 and acted quickly when they did.

In fact they had evidence even before this, if they bothered to put it together (in fact they stated a plan to do such statistical analyses but it’s not clear if they did them- or in any case there’s so far no evidence that they actually did these promised analyses).

In a previous study (“Table 13″), available in February of 2002, the could have seen that, comparing Vioxx to placebo, we saw a CVT event rate of 27/1087 = 0.0248 with Vioxx versus 5/633 = 0.0079 with placebo, with a p-value of 0.01. So, three times as likely.

In fact, there was an even earlier study (“1999 plan”), results of which were available in July of 2000, where the Vioxx CVT event rate was 10/427 = 0.0234 versus a placebo event rate of 1/252 = 0.0040, with a p-value of 0.05 (so more than 5 times as likely). This p-value can be taken to be the definition of statistically significant. So actually they knew to be very worried as early as 2000, but maybe they… forgot to do the analysis?

The FDA and Pooled Data

Where was the FDA in all of this?

They showed the FDA some of these numbers. But they did something really tricky. Namely, they kept the “osteoarthritis study” results separate from the “rheumatoid arthritis study” results. Each alone were not quite statistically significant, but together were amply statistically significant. Moreover, they introduced a third category of study, namely the “Alzheimer’s study” results, which looked pretty insignificant (more on that below though). When you pooled all three of these study types together, the overall significance was just barely not there.

It should be mentioned that there was no apparent reason to separate the different arthritic studies, and there is evidence that they did pool such study data in other places as a standard method. That they didn’t pool those studies for the sake of their FDA report is incredibly suspicious. That the FDA didn’t pick up on this is probably due to the fact that they are overworked lawyers, and too trusting on top of that. That’s unfortunately not the only mistake the FDA made (more below).

Alzheimer’s Study

So the Alzheimer’s study kind of “saved the day” here. But let’s look into this more. First, note that the average age of the 3,000 patients in the Alzheimer’s study was 75, it was a 48-month study, and that the total number of deaths for those on Vioxx was 41 versus 24 on placebo. So actually on the face of it it sounds pretty bad for Vioxx.

There were a few contributing reasons why the numbers got so mild by the time the study’s result was pooled with the two arthritis studies. First, when really old people die, there isn’t always an autopsy. Second, although there was supposed to be a DSMB as part of the study, and one was part of the original proposal submitted to the FDA, this was dropped surreptitiously in a later FDA update. This meant there was no third party keeping an eye on the data, which is not standard operating procedure for a massive drug study and was a major mistake, possibly the biggest one, by the FDA.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, Merck researchers created an added “filter” to the reported CVT events, which meant they needed the doctors who reported the CVT event to send their info to the Merck-paid people (“investigators”), who looked over the documents to decide whether it was a bonafide CVT event or not. The default was to assume it wasn’t, even though standard operating procedure would have the default assuming that there was such an event. In all, this filter removed about half the initially reported CVT events, and about twice as often the Vioxx patients had their CVT event status revoked as for the placebo patients. Note that the “investigator” in charge of checking the documents from the reporting doctors is paid $10,000 per patient. So presumably they wanted to continue to work for Merck in the future.

The effect of this “filter” was that, instead of it seeming 1.5 times as likely to have a CVT event if you were taking Voixx, it seemed like it was only 1.03 as likely, with a high p-score.

If you remove the ridiculous filter from the Alzheimer’s study, then you see that as of November 2000 there was statistically significant evidence that Vioxx caused CVT events in Alzheimer patients.

By the way, one extra note. Many of the 41 deaths in the Vioxx group were dismissed as “bizarre” and therefore unrelated to Vioxx. Namely, car accidents, falling of ladders, accidentally eating bromide pills. But at this point there’s evidence that Vioxx actually accelerates Alzheimer’s disease itself, which could explain those so-called bizarre deaths. This is not to say that Merck knew that, but rather that one should not immediately dismiss the concept of statistically significant just because it doesn’t make intuitive sense.

VIGOR and the New England Journal of Medicine

One last chapter in this sad story. There was a large-scale study, called the VIGOR study, with 8,000 patients. It was published in the New England Journal of Medicine on November 23, 2000. See also this NPR timeline for details. They didn’t show the graphs which would have emphasized this point, but they admitted, in a deceptively round-about way, that Vioxx has 4 times the number of CVT events than Aleve. They hinted that this is either because Aleve is protective against CVT events or that Vioxx is bad for it, but left it open.

But Bayer, which owns Aleve, issued a press release saying something like, “if Aleve is protective for CVT events then it’s news to us.” Bayer, it should be noted, has every reason to want people to think that Aleve is protective against CVT events. This problem, and the dubious reasoning explaining it away, was completely missed by the peer review system; if it had been spotted, Vioxx would have been forced off the market then and there. Instead, Merck purchased 900,000 preprints of this article from the NE Journal of Medicine, which is more than the number of practicing doctors in the U.S.. In other words, the Journal was used as a PR vehicle for Merck.

The paper emphasized that Aleve has twice the rate of ulcers and bleeding, at 4%, whereas Vioxx had a rate of only 2% among chronic users. When you compare that to the elevated rate of heart attack and death (0.4% to 1.2%) of Vioxx over Aleve, though, the reduced ulcer rate doesn’t seem all that impressive.

A bit more color on this paper. It was written internally by Merck, after which non-Merck authors were found. One of them is Loren Laine. Loren helped Merck develop a sound-byte interview which was 30 seconds long and was sent to the news media and run like a press interview, even though it actually happened in Merck’s New Jersey office (with a backdrop to look like a library) with a Merck employee posing as a neutral interviewer. Some smart lawyer got the outtakes of this video made available as part of the litigation against Merck. Check out this youtube video, where Laine and the fake interviewer scheme about spin and Laine admits they were being “cagey” about the renal failure issues that were poorly addressed in the article.

The Damage Done

Also on the Congress testimony I mentioned above is Dr. David Graham, who speaks passionately from minute 41:11 to minute 53:37 about Vioxx and how it is a symptom of a broken regulatory system. Please take 10 minutes to listen if you can.

He claims a conservative estimate is that 100,000 people have had heart attacks as a result of using Vioxx, leading to between 30,000 and 40,000 deaths (again conservatively estimated). He points out that this 100,000 is 5% of Iowa, and in terms people may understand better, this is like 4 aircraft falling out of the sky every week for 5 years.

According to this blog, the noticeable downwards blip in overall death count nationwide in 2004 is probably due to the fact that Vioxx was taken off the market that year.

Conclusion

Let’s face it, nobody comes out looking good in this story. The peer review system failed, the FDA failed, Merck scientists failed, and the CEO of Merck misled Congress and the people who had lost their husbands and wives to this damaging drug. The truth is, we’ve come to expect this kind of behavior from traders and bankers, but here we’re talking about issues of death and quality of life on a massive scale, and we have people playing games with statistics, with academic journals, and with the regulators.

Just as the financial system has to be changed to serve the needs of the people before the needs of the bankers, the drug trial system has to be changed to lower the incentives for cheating (and massive death tolls) just for a quick buck. As I mentioned before, it’s still not clear that they would have made less money, even including the penalties, if they had come clean in 2000. They made a bet that the fines they’d need to eventually pay would be smaller than the profits they’d make in the meantime. That sounds familiar to anyone who has been following the fallout from the credit crisis.

One thing that should be changed immediately: the clinical trials for drugs should not be run or reported on by the drug companies themselves. There has to be a third party which is in charge of testing the drugs and has the power to take the drugs off the market immediately if adverse effects (like CVT events) are found. Hopefully they will be given more power than risk firms are currently given in finance (which is none)- in other words, it needs to be more than reporting, it needs to be an active regulatory power, with smart people who understand statistics and do their own state-of-the-art analyses – although as we’ve seen above even just Stats 101 would sometimes do the trick.

Yesterday I caught a lecture at Columbia given by statistics professor David Madigan, who explained to us the story of Vioxx and Merck. It’s fascinating and I was lucky to get permission to retell it here.

Disclosure

Madigan has been a paid consultant to work on litigation against Merck. He doesn’t consider Merck to be an evil company by any means, and says it does lots of good by producing medicines for people. According to him, the following Vioxx story is “a line of work where they went astray”.

Yet Madigan’s own data strongly suggests that Merck was well aware of the fatalities resulting from Vioxx, a blockbuster drug that earned them $2.4b in 2003, the year before it “voluntarily” pulled it from the market in September 2004. What you will read below shows that the company set up standard data protection and analysis plans which they later either revoked or didn’t follow through with, they gave the FDA misleading statistics to trick them into thinking the drug was safe, and set up a biased filter on an Alzheimer’s patient study to make the results look better. They hoodwinked the FDA and the New England Journal of Medicine and took advantage of the public trust which ultimately caused the deaths of thousands of people.

The data for this talk came from published papers, internal Merck documents that he saw through the litigation process, FDA documents, and SAS files with primary data coming from Merck’s clinical trials. So not all of the numbers I will state below can be corroborated, unfortunately, due to the fact that this data is not all publicly available. This is particularly outrageous considering the repercussions that this data represents to the public.

Background

The process for getting a drug approved is lengthy, requires three phases of clinical trials before getting FDA approval, and often takes well over a decade. Before the FDA approved Vioxx, less than 20,000 people tried the drug, versus 20,000,000 people after it was approved. Therefore it’s natural that rare side effects are harder to see beforehand. Also, it should be kept in mind that for the sake of clinical trials, they choose only people who are healthy outside of the one disease which is under treatment by the drug, and moreover they only take that one drug, in carefully monitored doses. Compare this to after the drug is on the market, where people could be unhealthy in various ways and could be taking other drugs or too much of this drug.

Vioxx was supposed to be a new “NSAID” drug without the bad side effects. NSAID drugs are pain killers like Aleve and ibuprofen and aspirin, but those had the unfortunate side effects of gastro-intestinal problems (but those are only among a subset of long term users, such as people who take painkillers daily to treat chronic pain, such as people with advanced arthritis). The goal was to find a pain-killer without the GI side effects. The underlying scientific goal was to find a COX-2 inhibitor without the COX-1 inhibition, since scientists had realized in 1991 that COX-2 suppression corresponded to pain relief whereas COX-1 suppression corresponded to GI problems.

Vioxx Introduced and Withdrawn From the Market

The timeline for Vioxx’s introduction to the market was accelerated: they started work in 1991 and got approval in 1999. They pulled Vioxx from the market in 2004 in the “best interest of the patient”. It turned out that it caused heart attacks and strokes. The stock price of Merck plummeted and $30 billion of its market cap was lost. There was also an avalanche of lawsuits, one of the largest resulting in a $5 billion settlement which was essentially a victory for Merck, considering they made a profit of $10 billion on the drug while it was being sold.

The story Merck will tell you is that they “voluntarily withdrew” the drug on September 30, 2004. In a placebo-controlled study of colon polyps in 2004, it was revealed that over a time period of 1200 days, 4% of the Vioxx users suffered a “cardiac, vascular, or thoracic event” (CVT event), which basically means something like a heart attack or stroke, whereas only 2% of the placebo group suffered such an event. In a group of about 2400 people, this was statistically significant, and Merck had no choice but to pull their drug from the market.

It should be noted that, on the one hand Merck should be applauded for checking for CVT events on a colon polyps study, but on the other hand that in 1997, at the International Consensus Meeting on COX-2 Inhibition, a group of leading scientists issued a warning in their Executive Summary that it was “… important to monitor cardiac side effects with selective COX-2 inhibitors”. Moreover, in an internal Merck email as early as 1996, it was stated there was a “… substantial chance that CVT will be observed.” In other words, Merck knew to look out for such things. Importantly, however, there was no subsequent insert in the medicine’s packaging that warned of possible CVT side-effects.

What the CEO of Merck Said

What did Merck say to the world at that point in 2004? You can look for yourself at the four and half hour Congressional hearing (seen on C-SPAN) which took place on November 18, 2004. Starting at 3:27:10, the then-CEO of Merck, Raymond Gilmartin, testifies that Merck “puts patients first” and “acted quickly” when there was reason to believe that Vioxx was causing CVT events. Gilmartin also went on the Charlie Rose show and repeated these claims, even go so far as stating that the 2004 study was the first time they had a study which showed evidence of such side effects.

How quickly did they really act though? Were there warning signs before September 30, 2004?

Arthritis Studies

Let’s go back to the time in 1999 when Vioxx was FDA approved. In spite of the fact that it was approved for a rather narrow use, mainly for arthritis sufferers who needed chronic pain management and were having GI problems on other meds (keeping in mind that Vioxx was way more expensive than ibuprofen or aspirin, so why would you use it unless you needed to), Merck nevertheless launched an ad campaign with Dorothy Hamill and spent $160m (compare that with Budweiser which spent $146m or Pepsi which spent $125m in the same time period).

As I mentioned, Vioxx was approved faster than usual. At the time of its approval, the completed clinical studies had only been 6- or 12-week studies; no longer term studies had been completed. However, there was one underway at the time of approval, namely a study which compared Aleve with Vioxx for people suffering from osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

What did the arthritis studies show? These results, which were available in late 2003, showed that the CVT events were more than twice as likely with Vioxx as with Aleve (CVT event rates of 32/1304 = 0.0245 with Vioxx, 6/692 = 0.0086 with Aleve, with a p-value of 0.01). As we see this is a direct refutation of the fact that CEO Gilmartin stated that they didn’t have evidence until 2004 and acted quickly when they did.

In fact they had evidence even before this, if they bothered to put it together (in fact they stated a plan to do such statistical analyses but it’s not clear if they did them- or in any case there’s so far no evidence that they actually did these promised analyses).

In a previous study (“Table 13″), available in February of 2002, the could have seen that, comparing Vioxx to placebo, we saw a CVT event rate of 27/1087 = 0.0248 with Vioxx versus 5/633 = 0.0079 with placebo, with a p-value of 0.01. So, three times as likely.

In fact, there was an even earlier study (“1999 plan”), results of which were available in July of 2000, where the Vioxx CVT event rate was 10/427 = 0.0234 versus a placebo event rate of 1/252 = 0.0040, with a p-value of 0.05 (so more than 5 times as likely). This p-value can be taken to be the definition of statistically significant. So actually they knew to be very worried as early as 2000, but maybe they… forgot to do the analysis?

The FDA and Pooled Data

Where was the FDA in all of this?

They showed the FDA some of these numbers. But they did something really tricky. Namely, they kept the “osteoarthritis study” results separate from the “rheumatoid arthritis study” results. Each alone were not quite statistically significant, but together were amply statistically significant. Moreover, they introduced a third category of study, namely the “Alzheimer’s study” results, which looked pretty insignificant (more on that below though). When you pooled all three of these study types together, the overall significance was just barely not there.

It should be mentioned that there was no apparent reason to separate the different arthritic studies, and there is evidence that they did pool such study data in other places as a standard method. That they didn’t pool those studies for the sake of their FDA report is incredibly suspicious. That the FDA didn’t pick up on this is probably due to the fact that they are overworked lawyers, and too trusting on top of that. That’s unfortunately not the only mistake the FDA made (more below).

Alzheimer’s Study

So the Alzheimer’s study kind of “saved the day” here. But let’s look into this more. First, note that the average age of the 3,000 patients in the Alzheimer’s study was 75, it was a 48-month study, and that the total number of deaths for those on Vioxx was 41 versus 24 on placebo. So actually on the face of it it sounds pretty bad for Vioxx.

There were a few contributing reasons why the numbers got so mild by the time the study’s result was pooled with the two arthritis studies. First, when really old people die, there isn’t always an autopsy. Second, although there was supposed to be a DSMB as part of the study, and one was part of the original proposal submitted to the FDA, this was dropped surreptitiously in a later FDA update. This meant there was no third party keeping an eye on the data, which is not standard operating procedure for a massive drug study and was a major mistake, possibly the biggest one, by the FDA.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, Merck researchers created an added “filter” to the reported CVT events, which meant they needed the doctors who reported the CVT event to send their info to the Merck-paid people (“investigators”), who looked over the documents to decide whether it was a bonafide CVT event or not. The default was to assume it wasn’t, even though standard operating procedure would have the default assuming that there was such an event. In all, this filter removed about half the initially reported CVT events, and about twice as often the Vioxx patients had their CVT event status revoked as for the placebo patients. Note that the “investigator” in charge of checking the documents from the reporting doctors is paid $10,000 per patient. So presumably they wanted to continue to work for Merck in the future.

The effect of this “filter” was that, instead of it seeming 1.5 times as likely to have a CVT event if you were taking Voixx, it seemed like it was only 1.03 as likely, with a high p-score.

If you remove the ridiculous filter from the Alzheimer’s study, then you see that as of November 2000 there was statistically significant evidence that Vioxx caused CVT events in Alzheimer patients.

By the way, one extra note. Many of the 41 deaths in the Vioxx group were dismissed as “bizarre” and therefore unrelated to Vioxx. Namely, car accidents, falling of ladders, accidentally eating bromide pills. But at this point there’s evidence that Vioxx actually accelerates Alzheimer’s disease itself, which could explain those so-called bizarre deaths. This is not to say that Merck knew that, but rather that one should not immediately dismiss the concept of statistically significant just because it doesn’t make intuitive sense.

VIGOR and the New England Journal of Medicine

One last chapter in this sad story. There was a large-scale study, called the VIGOR study, with 8,000 patients. It was published in the New England Journal of Medicine on November 23, 2000. See also this NPR timeline for details. They didn’t show the graphs which would have emphasized this point, but they admitted, in a deceptively round-about way, that Vioxx has 4 times the number of CVT events than Aleve. They hinted that this is either because Aleve is protective against CVT events or that Vioxx is bad for it, but left it open.

But Bayer, which owns Aleve, issued a press release saying something like, “if Aleve is protective for CVT events then it’s news to us.” Bayer, it should be noted, has every reason to want people to think that Aleve is protective against CVT events. This problem, and the dubious reasoning explaining it away, was completely missed by the peer review system; if it had been spotted, Vioxx would have been forced off the market then and there. Instead, Merck purchased 900,000 preprints of this article from the NE Journal of Medicine, which is more than the number of practicing doctors in the U.S.. In other words, the Journal was used as a PR vehicle for Merck.

The paper emphasized that Aleve has twice the rate of ulcers and bleeding, at 4%, whereas Vioxx had a rate of only 2% among chronic users. When you compare that to the elevated rate of heart attack and death (0.4% to 1.2%) of Vioxx over Aleve, though, the reduced ulcer rate doesn’t seem all that impressive.

A bit more color on this paper. It was written internally by Merck, after which non-Merck authors were found. One of them is Loren Laine. Loren helped Merck develop a sound-byte interview which was 30 seconds long and was sent to the news media and run like a press interview, even though it actually happened in Merck’s New Jersey office (with a backdrop to look like a library) with a Merck employee posing as a neutral interviewer. Some smart lawyer got the outtakes of this video made available as part of the litigation against Merck. Check out this youtube video, where Laine and the fake interviewer scheme about spin and Laine admits they were being “cagey” about the renal failure issues that were poorly addressed in the article.

The Damage Done

Also on the Congress testimony I mentioned above is Dr. David Graham, who speaks passionately from minute 41:11 to minute 53:37 about Vioxx and how it is a symptom of a broken regulatory system. Please take 10 minutes to listen if you can.

He claims a conservative estimate is that 100,000 people have had heart attacks as a result of using Vioxx, leading to between 30,000 and 40,000 deaths (again conservatively estimated). He points out that this 100,000 is 5% of Iowa, and in terms people may understand better, this is like 4 aircraft falling out of the sky every week for 5 years.

According to this blog, the noticeable downwards blip in overall death count nationwide in 2004 is probably due to the fact that Vioxx was taken off the market that year.

Conclusion

Let’s face it, nobody comes out looking good in this story. The peer review system failed, the FDA failed, Merck scientists failed, and the CEO of Merck misled Congress and the people who had lost their husbands and wives to this damaging drug. The truth is, we’ve come to expect this kind of behavior from traders and bankers, but here we’re talking about issues of death and quality of life on a massive scale, and we have people playing games with statistics, with academic journals, and with the regulators.

Just as the financial system has to be changed to serve the needs of the people before the needs of the bankers, the drug trial system has to be changed to lower the incentives for cheating (and massive death tolls) just for a quick buck. As I mentioned before, it’s still not clear that they would have made less money, even including the penalties, if they had come clean in 2000. They made a bet that the fines they’d need to eventually pay would be smaller than the profits they’d make in the meantime. That sounds familiar to anyone who has been following the fallout from the credit crisis.

One thing that should be changed immediately: the clinical trials for drugs should not be run or reported on by the drug companies themselves. There has to be a third party which is in charge of testing the drugs and has the power to take the drugs off the market immediately if adverse effects (like CVT events) are found. Hopefully they will be given more power than risk firms are currently given in finance (which is none)- in other words, it needs to be more than reporting, it needs to be an active regulatory power, with smart people who understand statistics and do their own state-of-the-art analyses – although as we’ve seen above even just Stats 101 would sometimes do the trick.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)