Billions of pounds of British public money has gone to business, with Disney getting £170m. They really are taking the Mickey

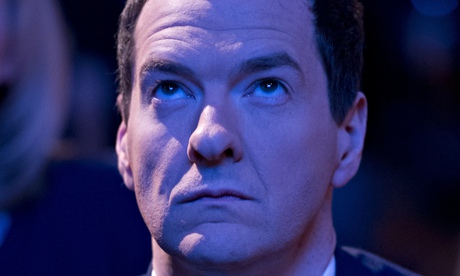

Last week, as the Tory faithful cheered on George Osborne’s new cuts in benefits for the working-age poor, a little story appeared that blew a big hole in the welfare debate. Tucked away in the Guardian last Wednesday, an article revealed that the British government had since 2007 handed Disney almost £170m to make films here. Last year alone the Californian giant took £50m in tax credits. By way of comparison, in April the government will scrap a £347m crisis fund that provides emergency cash for families on the verge of homelessness or starvation.

Benefits are what we grudgingly hand the poor; the rich are awarded tax breaks. Cut through the euphemisms and the Treasury accounting, however, and you’re left with two forms of welfare. Except that the hundreds given to people sleeping on the street has been deemed unaffordable. Those millions for $150bn Disney, on the other hand, that’s apparently money well spent –whoever coined the phrase “taking the Mickey” must have worked for HM Revenue.

Politicians and pundits talk about welfare as if it’s solely cash given to people. Hardly ever discussed is corporate welfare: the grants and subsidies, the contracts and cut-price loans that government hands over to business. Yet some of our biggest companies and industries operate a business model that depends on them extracting money from the British taxpayer. The operators of our supposedly privatised train services are kept afloat by billions in public money. Or take the firm created by billionaire Jeff Bezos: last year it emerged that Amazon had paid less in corporation tax to the UK than it had received in government grants.

The bill for corporate welfare is huge – and largely hidden. We know a lot about the people who claim social welfare: we know how much each benefit costs the public, the government sets strict rules for eligibility – and we even have detailed estimates for how much cheating goes on. Between them, Whitehall, academia and NGOs have churned out enough surveys on social welfare claimants to fill a wing of the Bodleian library. But corporate welfare? The government has itself acknowledged: “There is no definitive source of data about spending on subsidies to businesses in the UK.” The numbers are scattered across government publications and there is not even any agreement on what counts as a corporate handout.

Instead, what you get on the issue is silence. A very congenial silence for the CBI and other business lobby groups, who can urge ministers to cut benefits for the poor harder and faster, knowing their members are still getting their bungs. An agreeable silence for Osborne and David Cameron, who still argue that the primary problem in Britain is that the public sector “crowds out” private enterprise, without ever acknowledging how much the public subsidises business. Most of all, a silence at the very centre of our democracy.

Kevin Farnsworth, a senior lecturer in social policy at the University of York, has spent the best part of a decade studying corporate welfare – delving through Whitehall spreadsheets and others, and poring over Companies House filings. He’s just produced what is, as far as I know, the first ever comprehensive audit of the British corporate welfare state.

The figures, to be published in a forthcoming report, are astonishing. Farnsworth takes the financial year 2011-12 and tots up the subsidies and grants paid directly to businesses. They amount to over £14bn – that is, almost three times the £5bn paid out that year in income-based jobseeker’s allowance.

Add to that the corporate tax benefits, the value of the cheap credit made available to banks and other business, the insurance schemes run by the government to protect exporters, the marketing for British business laid on by Vince Cable’s ministry, the public procurement from the private sector … Farnsworth calculates that direct corporate welfare costs British taxpayers just shy of £85bn a year.

This, he admits, is a conservative estimate. I would throw in the public subsidy provided to too-big-to-fail banks, or the £25bn taxpayers shelled out that year in tax credits, housing and council tax benefits to people in work but not paid enough by their employers to live on. Nevertheless, Farnsworth has achieved something extraordinary: he has yanked into the open an £85bn subsidy that big business and the government would rather you didn’t know about.

Thinking over this giant corporate bung, two responses immediately suggest themselves. First, it shows up the stupidity of all those newspaper spreads and BBC discussions constantly demanding “What would you cut?”, like some middlebrow ransom note (“Choose now: or the lollipop lady gets it”). It’s a question you’ll be hearing more and more in the run-up to the election. Perhaps next time, as well as mentioning schools, fire services and benefits, some brave Radio 4 presenter will mention the business coaching and marketing and advocacy services provided by the Department for Business (annual cost: nearly £5bn).

The other response you might make is that some business funding is inevitable, even desirable. Perhaps you consider keeping Kenneth Branagh employed in these islands to be a national priority – in which case, roll on those tax reliefs for Disney. I might argue that renewable energy deserves a subsidy. But voters are at least entitled to an informed debate. That is precisely what we’ve not been allowed, through the deliberate obscuring of these sums.

And if taxpayers are to fund corporations, why shouldn’t they demand that those businesses observe certain conditions of basic fairness? The publicly funded train operators should pay their staff living wages, provide decent pensions and sick pay. And all recipients of public money should be banned from using elaborate structures to avoid paying tax.

Our semi-secret system makes no such demands: of the 44 companies that received over £1m in government grants between 2005 and 2011, 13 didn’t pay any corporation tax at all; a further 17 didn’t pay any corporation tax either the year before or the year of receiving their public money. These aren’t two-bit firms, either: Farnsworth’s list includes Tesco Personal Finance, Dell and Plusnet.

And, of course, Amazon – which in 2011 alone took £7.7m from Holyrood for placing a distribution centre in Fife. The Welsh assembly promised it even more: £8.8m, as well as a £3m highway to connect its operations with other road networks. Just finished, it’s called the Ffordd Amazon road, for the avoidance of ambiguity about whose interests it’s meant to serve.

Farnsworth’s research should trigger a public debate about the size and uses of the corporate welfare state. Personally, I’ll believe we’re getting somewhere when Channel 4 puts on Corporate-Benefits Street – with White Dee replaced by Amazon founder and inveterate tax-dodger Jeff Bezos.