The self-serving con of neoliberalism is that it has eroded the human values the market was supposed to emancipate

To be at peace with a troubled world: this is not a reasonable aim. It can be achieved only through a disavowal of what surrounds you. To be at peace with yourself within a troubled world: that, by contrast, is an honourable aspiration. This column is for those who feel at odds with life. It calls on you not to be ashamed.

I was prompted to write it by a remarkable book, just published in English, by a Belgian professor of psychoanalysis, Paul Verhaeghe. What About Me? The Struggle for Identity in a Market-Based Society is one of those books that, by making connections between apparently distinct phenomena, permits sudden new insights into what is happening to us and why.

We are social animals, Verhaeghe argues, and our identities are shaped by the norms and values we absorb from other people. Every society defines and shapes its own normality – and its own abnormality – according to dominant narratives, and seeks either to make people comply or to exclude them if they don’t.

Today the dominant narrative is that of market fundamentalism, widely known in Europe as neoliberalism. The story it tells is that the market can resolve almost all social, economic and political problems. The less the state regulates and taxes us, the better off we will be. Public services should be privatised, public spending should be cut, and business should be freed from social control. In countries such as the UK and the US, this story has shaped our norms and values for around 35 years: since Thatcher and Reagan came to power. It is rapidly colonising the rest of the world.

Verhaeghe points out that neoliberalism draws on the ancient Greek idea that our ethics are innate (and governed by a state of nature it calls the market) and on the Christian idea that humankind is inherently selfish and acquisitive. Rather than seeking to suppress these characteristics, neoliberalism celebrates them: it claims that unrestricted competition, driven by self-interest, leads to innovation and economic growth, enhancing the welfare of all.

At the heart of this story is the notion of merit. Untrammelled competition rewards people who have talent, work hard, and innovate. It breaks down hierarchies and creates a world of opportunity and mobility.

The reality is rather different. Even at the beginning of the process, when markets are first deregulated, we do not start with equal opportunities. Some people are a long way down the track before the starting gun is fired. This is how the Russian oligarchs managed to acquire such wealth when the Soviet Union broke up. They weren’t, on the whole, the most talented, hardworking or innovative people, but those with the fewest scruples, the most thugs, and the best contacts – often in the KGB.

Even when outcomes are based on talent and hard work, they don’t stay that way for long. Once the first generation of liberated entrepreneurs has made its money, the initial meritocracy is replaced by a new elite, which insulates its children from competition by inheritance and the best education money can buy. Where market fundamentalism has been most fiercely applied – in countries like the US and UK – social mobility has greatly declined.

If neoliberalism was anything other than a self-serving con, whose gurus and thinktanks were financed from the beginning by some of the world’s richest people (the US multimillionaires Coors, Olin, Scaife, Pew and others), its apostles would have demanded, as a precondition for a society based on merit, that no one should start life with the unfair advantage of inherited wealth or economically determined education. But they never believed in their own doctrine. Enterprise, as a result, quickly gave way to rent.

All this is ignored, and success or failure in the market economy are ascribed solely to the efforts of the individual. The rich are the new righteous; the poor are the new deviants, who have failed both economically and morally and are now classified as social parasites.

The market was meant to emancipate us, offering autonomy and freedom. Instead it has delivered atomisation and loneliness.

The workplace has been overwhelmed by a mad, Kafkaesque infrastructure of assessments, monitoring, measuring, surveillance and audits, centrally directed and rigidly planned, whose purpose is to reward the winners and punish the losers. It destroys autonomy, enterprise, innovation and loyalty, and breeds frustration, envy and fear. Through a magnificent paradox, it has led to the revival of a grand old Soviet tradition known in Russian as tufta. It means falsification of statistics to meet the diktats of unaccountable power.

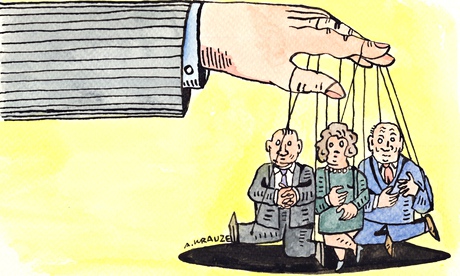

The same forces afflict those who can’t find work. They must now contend, alongside the other humiliations of unemployment, with a whole new level of snooping and monitoring. All this, Verhaeghe points out, is fundamental to the neoliberal model, which everywhere insists on comparison, evaluation and quantification. We find ourselves technically free but powerless. Whether in work or out of work, we must live by the same rules or perish. All the major political parties promote them, so we have no political power either. In the name of autonomy and freedom we have ended up controlled by a grinding, faceless bureaucracy.

These shifts have been accompanied, Verhaeghe writes, by a spectacular rise in certain psychiatric conditions: self-harm, eating disorders, depression and personality disorders.

Of the personality disorders, the most common are performance anxiety and social phobia: both of which reflect a fear of other people, who are perceived as both evaluators and competitors – the only roles for society that market fundamentalism admits. Depression and loneliness plague us.

The infantilising diktats of the workplace destroy our self-respect. Those who end up at the bottom of the pile are assailed by guilt and shame. The self-attribution fallacy cuts both ways: just as we congratulate ourselves for our success, we blame ourselves for our failure, even if we have little to do with it.

So, if you don’t fit in, if you feel at odds with the world, if your identity is troubled and frayed, if you feel lost and ashamed – it could be because you have retained the human values you were supposed to have discarded. You are a deviant. Be proud.