|

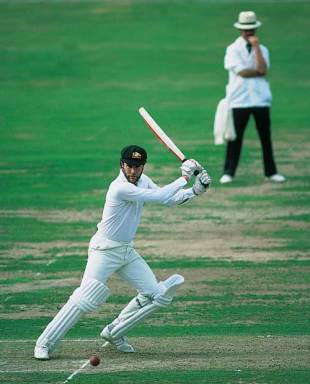

| Mike Brearley: "For many people otherwise inclined to be inhibited or self-conscious, sport offers a unique opportunity for self-expression and spontaneity" © Getty Images |

| Enlarge

|

|

|

|

Thank you very much for these remarks; and above all for the great honour you do me in inviting me to give the Bradman Oration as No. 11 in the distinguished line-up of speakers. There are those who'd say that this is the most appropriate position for me in the batting order, though I reckon I might get in ahead of Tim Rice.

It is an honour: but an intimidating honour. Following Rahul Dravid, for one thing. And he himself said it made him more anxious than going in to bat at No. 3 for India at the MCG. For another thing, it's not a talk you invite me for, or a mere lecture, or even a speech, but an Oration, no less. An imposing word and an imposing task. And not only an Oration, but what about the other word in the title: Bradman! The greatest batsman the game has known, a tireless administrator, and a man whose words are shrewd and moving.

It is just possible that the names Bradman and Brearley are not indissolubly linked together in the minds of cricket lovers, except perhaps for those who study the alphabetical order of England-Australia Test players, in which list we are separated solely by Len Braund, who played in 23 Tests for England in the first decade of the 20th century. A heckler in Sydney did once link Bradman and me during the fourth Test of 1978-79: "Breely," he shouted, "you make Denness look like Bradman."

However, I have one Test batting statistic that makes me superior to Don Bradman. I daresay many of you don't know this fact, one that is hard to believe, but of his 80 Test innings no fewer than ten ended in ducks: once in eight times he went to the crease in Test cricket, Bradman was out for nought. A remarkable fact. Whereas in my Test career, of 66 innings only six were ducks, one in 11.

I met Sir Donald a few times on my tours of Australia. Doug Insole, Ken Barrington, Bob Willis and I had lunch with him in Adelaide in 1978. I liked him - he was spry, quick, trenchant and modest. He had a twinkle in his eye. I remember best the discussion about fast bowlers. He reckoned that, for about 18 months, Frank Tyson was the fastest he'd seen; and that Harold Larwood was quicker than the bowlers of that day (who included Michael Holding, Andy Roberts, Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson - no slouches you'll agree). He acknowledged that Rodney Hogg was, as he put it, "a bit slippery". I thought he was too.

I come to Australia at a good time for English cricket, and at a key moment, I suspect, for Australian cricket. We are between two Ashes series, unusually close together. As you may have noticed, England have won four of the last five series, though I hesitate, as you'd appreciate, to rub it in. Australians, I gather, are baffled and confused by this scenario, one matched by parallel declines in other sports. It must be a time of soul-searching. I look forward very much to the upcoming series.

So - what to talk to you about, what to orate on? There are so many possible current topics - Test cricket and the threat of T20 domestic leagues, Umpire Review Systems, including the hot spot of Hot Spot, how to fight corruption in sport and in particular in cricket; and so on. But I imagine you might be a little tired of these issues (some of which will no doubt come up in the Panel), and I'm not sure I have anything original to say on them. So I've decided to talk to you now about something that borders on the work I've been doing as a psychoanalyst for the last 30-plus years since stopping playing cricket. I should like to consider the question: what is the point of sport, and in particular of cricket? And how does this link with the Ashes?

So: what is the point of it? Here are two quotes:

"Nothing in cricket has the slightest importance when set against a single death from violence in Northern Ireland."

And, second: ''Some people believe football is a matter of life and death. I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that."

The first quote was from John Arlott, the second, Bill Shankly, the charismatic manager of Liverpool Football Club. What are we to make of this apparent conflict?

| | | | |

| |

| "If human beings were not combative no one would have invented sport. But if human beings were not also cooperative neither team nor individual games would have come into existence" |

| |

| | |

|

The roots of sport

For those to whom sport doesn't appeal, it seems futile, pointless. They remember hours of misery at compulsory school games on cold (or indeed hot) sporting fields. They were perhaps physically awkward, and picked last; one can understand what a torment all this must have been for many.

Yet every small child, before self-doubt, and comparison with other children, gets a grip, takes pleasure in his or her bodily capacities and adroitness. Gradually the child achieves a measure of physical coordination and mastery. Walking, jumping, dancing, catching, kicking, climbing, splashing, using an implement as a bat or racquet - all these offer a sense of achievement and satisfaction. Sport grows out of the pleasure in such activities.

Moreover, this development in coordination is part of the development of a more unified self. Instead of being subject, as babies, to more or less random, stimulus-response movements of our limbs, we learn to act in the world according to central intentions or trajectories. We begin to know what we are doing and what we are about. The small child gradually finds a degree of rhythm and control through and in its movements. And there is the pleasure of improving.

So far, dance and sport are barely distinguishable. Sport proper starts to emerge when competition with others plays a more central role alongside the simpler delight in physicality. "I can run faster than you, climb higher, wrestle you to the floor." Aggression enters in more obviously, to combine with the flamboyance that is already in place.

Spontaneity and discipline

Sport is an area where aggression and the public demonstration of skills and of character are permitted, even encouraged. For many people otherwise inclined to be inhibited or self-conscious, sport offers a unique opportunity for self-expression and spontaneity. Within a framework of rules and acceptable behaviour, sportspeople can be whole-hearted. Such people - including me - owe sport a lot; here we begin to find ourselves, to become the selves that we have the potential to be.

In this process, the child and the adult have to learn to cope with the emotional ups and downs of victory and defeat, success and failure. They - we - gradually manage to keep going against the odds, to struggle back to form, to recognise the risks of complacency. We have to learn to deal with inner voices telling us we are no good, and with voices telling us we're wonderful. In sport the tendencies to triumph when we do well, and to become angry or depressed at doing badly, are often strong; we have to find our own ways of coping with them. Arrogance and humiliation have to be struggled against, whilst determination and proper pride and good sportsmanship are struggled towards.

Spectators identify not only with the skills of sportsmen but also with their characters, their characteristic ways of facing those twin impostors success and failure. These scenarios are central dramas of sport.

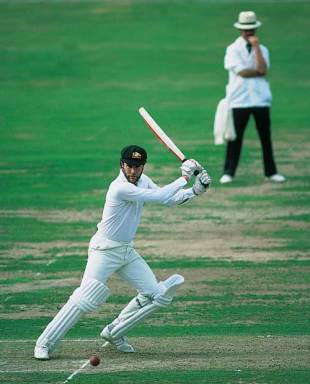

Sport calls too for a subtle balancing of planning and spontaneity, of calculation and letting go, of discipline and freedom. Greg Chappell wrote in an email to me: "premeditation is the graveyard of batting". And though this is importantly true, it needs qualification or expansion; for two reasons. One is that we need to set ourselves in certain ways. A batsman playing in a T20 match has a totally different orientation to the task from a player in a Test match. In one context he or she is looking to score off every ball; he is aware of the pressure of time, and of the urgent need to evaluate quickly where his side should be in two overs, say, or five. And second the advice may be in some cases a counsel of perfection, aimed at a highly skilled player, and geared to a scenario in which there is infinite time. All batsmen have to do some premeditation, if only in ruling out certain options. Even that mercurial genius Denis Compton looked to be on the back foot when facing quick bowlers. Most players pre-decide whether to go for the hook or alternatively to defend or evade the short-pitched ball; they adopt a policy; they premeditate. In shorter games, all batsmen pre-determine, or at least have a range of possibilities in their minds.

Also one has to train oneself in the sporting skills, form a reliable technique, and work at it. But - and this I think is Greg's point - having disciplined ourselves, having set ourselves according to the situation of the game, we then have to let ourselves go, trusting to our craftsmanship, skill and intuitive responsiveness, without further interference from the conscious mind. Occasionally this leads to that sublime balance between elements that constitutes being in the zone, or being on form. At the peak of performance one is simultaneously alert to possible lines of attack by individual and collective opponents, and able to respond with more or less uncluttered minds to the next play or assault. Like parents with children, we have a complicated job to do in enabling our own selves to find the right balance between self-discipline and free rein. The moments when body and mind are at one, when we are completely concentrated and completely relaxed, aware of every relevant detail of the surroundings but not obsessed or hyper-sensitive to any set of them, confident without being over-confident, aware of dangers without being over-cautious - such rare states of mind are akin to being in love. They involve a marriage between the conscious control mentioned above with the allowing of a more unconscious creativity through the body's knowledge. In such states the role of the conscious mind is, as Greg says, to stand back and quietly watch.

Teams

Sport divides into team and individual sports. One of the aims of team sport is for a group of individuals to be transfigured from a collection into a team, from a group functioning either like a homogenous flock or as a bunch of disparate individualists into a team with a range of different roles, with room for individual expression that is to be kept subservient to the cohesion of the whole team. Team sport calls for the balancing of self-interest and group interest. The members of the team have at times to constrain themselves in the interests of the team; they also have the benefit of the team's support especially when things are hard for them individually.

Cricket is unusual. Like baseball, but unlike golf or football, it is a matter of individual contests and dramas within a team context. When Chris Rogers opens the batting against Jimmy Anderson at Brisbane in a month's time, he will be well aware that what happens next is up to him (and Anderson). But their battle will also at some more subliminal level be influenced by the morale of the two sides.

|

| Greg Chappell once said "premeditation is the graveyard of batting" Adrian Murrell / © Getty Images |

| Enlarge

|

|

|

As Bradman said about the Invincibles (the 1948 side touring England): "Nothing can alter the figures which will appear in black and white in the record books, but they cannot record the spirit which permeated the side, the courage and fighting qualities of the players, for these things cannot be measured. They were on a very high plane."

Unlike baseball, cricket's contests between bat and ball can last for very long time periods - days, even - and go through many ups and downs. A weather-vane in the shape of Father Time surveys Lord's, the "home of cricket" - symbolising both the fact that time brings everything to an end and, perhaps, the timelessness of the experience of watching and playing cricket. Cricket is unique in its potential for drawn-out struggles between two people, each with his or her powerful narcissistic wishes for admiration and fears of humiliation, all within this team context. And for the cricket batsman failure means a symbolic death; he or she has to leave the arena, a king deposed.

Team games give people a sense of belonging and a proper pride. And this can happen not on the small scale of a single team, but on a national scale. Sport may be the one place where a country can come together with good feelings about itself. This has happened through cricket in Afghanistan, whose national team have worked their way up from Division 5 in the World Cricket League in 2008, to winning through as qualifiers for the next World Cup in 2015. Imagine what this means to a country devastated by wars, corruption and poverty.

Co-operation and competition

If human beings were not combative no one would have invented sport. But if human beings were not also cooperative neither team nor individual games would have come into existence. For reasons I will come to, rivalry can - and indeed should - be taken close to the limit. But alongside this, cricket also involves the recognition of the unspoken realities of the spirit, respect and generosity of the game. This is not merely a matter of obedience to the laws; it also involves ordinary civilities that oil the wheels of relationships and collegial activities, recognition of limits, consideration and respect, and give and take through a kind of dialogic interplay on the field.

The Latin etymology of both "rival" and "compete" reflect this fact: rivalis meant "sharing the same stream or river bank", competens meant "striving together with", "agreeing together", as in "competent."

Rivalry does not entail lack of respect for one's opponent, whatever the outcome. Test cricket is, like many other forms of sport, rightly a tough business. But there is another side of these tough contests which can too easily be forgotten, and that is the fair-mindedness and sportsmanship between hard, high-powered competitors. One occurred in the last innings of the Centenary Test in 1977, when Derek Randall made his fantastic 174 and Dennis Lillee took 11 wickets in the match (the result of which was precisely the same as the result of the original match, 100 years before, a 45-runs win for Australia). Randall was well past a century at this point, England were something like 250 for 2, Lillee was tired, and there was a serious chance of us winning against all odds. Greg, the captain, was bowling, and a ball squeezed between Randall's bat and pad. Rod Marsh dived forward to take the ball, and the batsman was given out. Picking himself up, Rod indicated to Greg that the ball hadn't carried, and Randall was called back. (Rod says it was also a fact that Randall hadn't even hit it, but that was another matter!)

When at Edgbaston in 2005 England won by two runs, England's hero Andrew Flintoff left the team huddle at the moment of victory and put his arm round his defeated opponent, Brett Lee. He was not only commiserating with the pain of defeat, a boot that could so easily have been on the other foot. He also I think was acknowledging the kinship between rivals. For at the same time as wanting to defeat our opponents, we depend on them and their skill, courage and hostility, in order to prove and improve our own skills, to earn and merit our pride. There is a unity of shared striving, as well as a duality of opposition. The 11 players on each team form bonds through their shared skills and teamwork that are sometimes hard to replicate in the less intense working relationships of everyday life. After wars, the closeness felt with fellow soldiers may make domestic ties for discharged survivors pallid by comparison. Somewhat similarly, the 22 players in a Test match go through it together, in a way that no spectator does.

Envy and jealousy play a part in, and are not always easily accommodated within, ordinary rivalry. In one county match Dickie Dodds, the Essex opening batsman, was out without scoring on a pitch that was perfect for batting. Essex went on to dominate the morning session, and by lunch had reached 150 without further loss. Having had to watch his team's success from the pavilion, Dodds camep to Doug Insole, one of the "not out" batsmen, and said, "Skipper, I hope you haven't been troubled by any bad vibes this morning?" Insole replied, "Can't say I have, Dickie, been too busy enjoying myself - why do you ask?" "Because I've been so full of bitterness I've not been wishing you well." Here is an understandable and very human envy; Dodds' frankness and regret meant there was no chance of it spoiling the relationship.

| | | | |

| |

| "Competitiveness can turn into bullying, uncouthness or superiority. But it can also be perverted in the opposite direction. Some people refrain from competing wholeheartedly because they are afraid of winning, and even avoid doing so" |

| |

| | |

|

In 1976-77, I played five Tests in India. One of India's formidable quartet of spin bowlers was Erapalli Prasanna. He was a short, somewhat rotund offspinner, with large, expressive eyes, and a wonderful control of flight. For some reason, he and I would engage in a kind of eye-play. His look would say, "Okay, you played that one all right, but where will the next one land?" And mine would reply, "Yes, you fooled me a little, but notice I adjusted well enough." He had that peculiarly Indian, minimal, sideways waggle of the head, which suggests that the vertebrae of the subcontinental neck are more loosely linked than in our stiffer Western ones. The waggle joined with the eyes in saying: "I acknowledge your qualities, and I know you acknowledge mine."

I found it easier to enter into such an engagement with a slow bowler, who might bamboozle me and get me out, but wasn't trying to kill me. But I had something similar with some fast bowlers, especially when we were more or less equally likely to come out on top. With them I could actually enjoy their best ball, pitching on a perfect length in line with off stump and moving away. I also enjoyed the fact that it was too good to graze the edge of my bat. There was the same friendly rivalry. The spirit of cricket - or more broadly, of sport itself.

Being tested

But how much do we really desire to be tested, in life or in sport? If the opposition's best fast bowler treads on the ball before the start of a Test match (as Glenn McGrath did just before the Edgbaston match referred to above) and cannot play, is one relieved or disappointed? There is no escaping the relief. We all want an easier ride. And it would be easy to be hypocritical, falsely high-minded, and say insincerely that we regret that the opposition team is hampered. But at the same time there is also a wish - in the participants as well as among spectators - for the contest to be fought with each side at its best, not depleted, so that no one can cavil at victory or make excuses for defeat. Similarly, one might take more pleasure in scoring fifty against Lillee and Thomson than in making a big hundred against lesser bowling. Bradman made a parallel point: "There is not much personal satisfaction in making a hundred and being missed several times. Any artist must surely aim at perfection." "Perfection" includes competing with the best, and this offers the opportunity to feel most fully alive, and to find the greatest satisfaction.

Opponents challenge us. If we are up to it, they stretch us, call forth our courage, skill and resourcefulness; they force us to develop our techniques, or else to lag behind. They are co-creators of excellence and integrity. As the old Yorkshire and England batsman Maurice Leyland once said: "Fast bowling keeps you honest." And mountaineer Heinrich Harrrer, in The White Spider, "The glorious thing about mountains is that they will endure no lies." And this is why corruption - fixing of any kind - goes against the essence of sport and is the greatest threat to its integrity.

Visceral truthfulness is part of the process whereby we come to accept the urgency of our own subjectivity, whilst giving room to the subjectivity of the other. It takes courage to risk all in such competitiveness, and courage and generosity to accept the outcome without retreat or revenge. You will agree that this is pat of the appeal of the Ashes to us all.

Avoiding the contest

Competitiveness can get out of hand, turning into cheating and a nasty vindictiveness. Over-valuation of competitiveness can crush and inhibit the growing child. It can spoil relationships, and reduce love to trophy-seeking. It can result in an attitude of "devil take the hindmost".

There is I think no need for "sledging", and I encountered hardly any of it in my career as a professional cricketer, In my experience the great West Indian fast bowlers said nothing to the batsman on the field. One might say: they had no need to - first because of their superlative ability, but second because they were quite able to convey menace by eye contact and strut. It happened that, when I played my first Test match, against the West Indies, in 1976, both teams were staying at the same hotel in Nottingham and I ran into Andy Roberts at breakfast. He gave me a quizzical little look, not crudely unpleasant, but conveying, I felt, something along the lines of "Shall I be eating you for breakfast or for tea?" He gave these looks on the field too. Like the face of Helen of Troy, which launched a thousand ships, Andy's conveyed a thousand words.

|

| Erapalli Prasanna, says Brearley, would engage the batsmen in eye-play © PA Photos |

| Enlarge

|

|

|

There are differences that would be hard to define between appropriate shrewdness in undermining an opponent and sledging - a boorish expression of contempt. Cricket is after all not only a physical game; it includes bluff, menace, ploy and counter-ploy. Setting a field is not simply a matter of putting someone where the ball is most likely to go, (though that's not a bad idea; have modern captains forgotten about third man?) but also of making the batsman wonder what is coming next, or making clear to him that we reckon he lacks certain strokes. The aim is that he will be undone by such a "statement" either into loss of nerve or into reckless attempts to prove us wrong. Words may enter into this; a captain might say within a batsman's hearing "you don't need anyone back there for him" - and I would be inclined to see this as a fair enough nibble at the batsman's state of mind. Viv Richards' swagger at the crease and Shane Warne's slow, mesmerising nine-step walk which took up most of his so-called "run-up" were key elements in their unequivocal assertion that this was their stage, a stage their opponents had little right to share with them. Such attitudes, by captains as well as bowlers or batsmen, seem to me to be acceptable, even admirable, but they can tip over into arrogance and superiority - even into a sort of gang warfare. The line is thin.

Superiority and arrogance may be endemic in a person or a culture. The British Empire was not exactly free of it (as you may have noticed). We British had many terms of abuse or disparagement for members of other cultures - racist stereotyping. Such automatic attitudes involved stereotyping. What was remarkable about the rise of West Indian cricket - a rise that culminated in their extraordinary period of world dominance during the 1970s and '80s - is that people who had been enslaved and then released into a world of prejudice, arrogance and power, with many of these arrangements extending into cricket, should have been so open to values that they found in this colonial game.

Self-disparagement is one consequence of racial and other kinds of trauma, yet cricketers like the Constantines (father Lebrun and son Learie), George Headley and Frank Worrell were able through their exploits and attitudes to build up the self-respect of their fellows, so that later generations could be stronger, more determined, more in touch with their proper pride. It seems to me that West Indians of earlier generations were able to be modest (in the sense of knowing they had a lot to learn) without being abject, and proud without being arrogant. They were prepared to celebrate the glass as half-full rather than rage against its being half-empty. They were willing also to wait. It was thanks to their pride and forbearance that the next generation, Roberts and Richards included, could triumph so memorably in what was able to be, by then, healthy competition between true equals.

So: competitiveness can turn into bullying, uncouthness or superiority. But it can also be perverted in the opposite direction. Some people refrain from competing wholeheartedly because they are afraid of winning, and even avoid doing so. One young boy desperately wanted to win the first board game with his father, but then equally desperately needed to lose the second, so that neither party would lose face, or have to bear too much disappointment, or have to deal with any tendency to gloat. One might think, loftily, that the mature attitude to winning in sport is not to mind. The opposite is true. Not minding often means avoiding really trying.

I am aware, of course, that recreational sport played for fun may have other aims and values. Of one social-side captain it was said that "his captaincy had twin aims: to give every player a good game and to beat the opposition as narrowly as possible". I can see the point in this. But something is also lost in such an attitude. In sport we have the opportunity, and the license, to assert ourselves as separate and authentic individuals against others who have the same license; this potential allows us to find our own unique identity, whilst respecting that of others. And this is part of a wider growth of the personality, of which one aspect would be the Quaker capacity to "tell Truth to Power". One element in telling the truth is being able to stand firm against powerful and sometimes bullying forces, without becoming a bully oneself. The more strenuous and spirited aspects of competitiveness enhance self-development, courage and sheer exhilaration. They can also be the occasion and source of the discovery and growth of new methods and techniques. Whereas being less than wholehearted is liable to be, though it may not be, a kind of evasion or cowardice.

I once was a guest player for an English professional side on a short tour involving a number of matches. During the first half of the tour, we had tried our best but lost more than we won. We had been facing talented players, in their conditions. The matches were played hard, even though they were not part of any ongoing competitive leagues or series. In the next game, against a very strong side, we were led by the newly arrived captain. This captain preferred to emphasise the entertainment element in the game, this being a supposedly "friendly" fixture; not wanting to be too serious, he took off his front-line bowlers, allowing the opposition batsmen to display their most powerful strokes. They scored an even bigger total than they would have without his (to my mind misguided) generosity, bowled flat-out against us, and we limped to a crushing defeat. This gesture of "giving" runs patronised the other team and robbed each party of the satisfaction of doing their best in striving properly to win. We did not properly lose (though we did lose face and respect). The gilt on our opponents' win was tarnished.

Such dilution of proper rivalry can also occur out of a wish to look good. One Test captain, whom I won't name, decided during the afternoon of the last day that his batsmen should play for a draw rather than take further risks in going for a win - a perfectly respectable decision. He was, however, reluctant to be criticised for being a defensive captain. This match was the first Test for a young batsman in the middle order; he had been given out (incorrectly) for a duck in the first innings, and given a hard time by the crowd, who'd wanted their local hero selected instead of him. When he went in to bat that last afternoon the captain gave him the following orders: "Play for a draw, but don't make it look as if we're playing for a draw." This was hypocritical and cowardly captaincy; the debutant was in a difficult enough place without having to act a false role. This captain was more interested in how he himself looked than in competing properly or in supporting a young player.

| | | | |

| |

| "It seems to me that West Indians of earlier generations were able to be modest (in the sense of knowing they had a lot to learn) without being abject, and proud without being arrogant" |

| |

| | |

|

I even have some doubts about what was from one viewpoint a notable example of nobility and generosity. The great Surrey and England batsman Jack Hobbs said once that as Surrey had a lot of good batsman, and the Oval pitch was usually easy, when he and Andy Sandham had put on 150 or so for the first wicket, he'd sometimes give his wicket to "the most deserving professional bowler". (When the pitch was difficult, or Larwood and Voce were bowling, that was when he really earned his money, he went on). But in making a gift of his wicket, did Hobbs belittle the recipient of the gift, who had not by his own skill and persistence forced an error? Did he treat the bowler not man to man, but man to boy? Was there an element of the feudal in Hobbs' largesse?

When England were about to tour India in 1976, some of us took the opportunity to ask Len Hutton, a Yorkshireman noted for his dry, enigmatic comments, for advice. Len appeared characteristically guarded. He then uttered a single short sentence: "Don't take pity on them Indian bowlers."

In the great battles of sport, no quarter is given and none expected. Some of you will remember the contest between South African fast bowler Alan Donald and Michael Atherton at Trent Bridge in 1998. A great fast bowler hurled all his aggression, power and skill at a defiant, gritty batsman, a battle given an extra tinge of menace by the umpiring mistake as a result of which Atherton had just been given not out, having gloved Donald to the keeper.

These are occasions when observers tremble with awe. Highlights of Test matches in Australia were for the first time broadcast in the UK in 1974-75, after the ten o'clock news. England - this you will certainly remember - were blasted by Lillee and Thommo on bowler-friendly pitches. My Middlesex colleague, opening batsman Mike Smith, reported pouring himself a large gin and tonic and hiding behind the sofa to watch.

In that series, Tony Greig used to provoke Lillee; he believed that Dennis bowled less well the more fired up he got; and Tony himself reacted at his best when the opponent was incensed. Some of the most memorable contests are those where the aggression is raw, but contained, perhaps only just, within the bounds of respect for the opposition and for the rules and traditions of the game. One of the great things about Ashes matches is the absolute commitment of both sides.

Shankly and Arlott

So to return, briefly, to John Arlott and Bill Shankley. Arlott is clearly right about particular moments. Death or serious injury are real tragedies or disasters, compared with which a low score, even a Bradman duck, is nothing. On the other hand, the institution of sport, with its challenges and opportunities, its companionship with team-mates and opponents alike, offers a setting for activities that enrich life, that build character, and that help develop the complex balance between being an individual and being part of a group or team. Both are right.

All Black or Black Caps? © Getty Images

All Black or Black Caps? © Getty Images