There will be some noticeable changes to the game when cricket resumes from its Covid-19 hiatus with one of the major differences being the way the ball is polished.

It's critical administrators produce the right response to the health challenges as swing bowling, along with wristspin, is a crucial part of attacking cricket. Both skills place a high priority on wicket-taking and need to be encouraged at every opportunity.

An outswing bowler is seeking the edge to provide a catch behind the wicket. The inswinger is delivered in search of a bowled or an lbw decision. In both cases, the bowler, in seeking the perfect ambush, is also providing the batsman with a driving opportunity as the ball needs to be pitched full to achieve the desired outcome.

Either way two results are in play - a wicket or a boundary - which creates the ideal balance of tension and expectation. Fans crave a genuine contest between bat and ball and that's part of what attracts them to the game in the first place.

With ball-tampering always a hot topic, in the past I've suggested that administrators ask international captains to construct a list (i.e. the use of natural substances) detailing the things bowlers feel will help them to swing the ball. From this list, the administrators should deem one method to be legal with all others being punishable as illegal.

With cricket on hold, this is the ideal time to conduct the exercise. Using saliva and perspiration are now seen as a health hazard, so bowlers require something to replace the traditional methods of shining the ball.

And while they are in a magnanimous mood, the administrators should also make a change to the lbw law that would be welcomed by all bowlers.

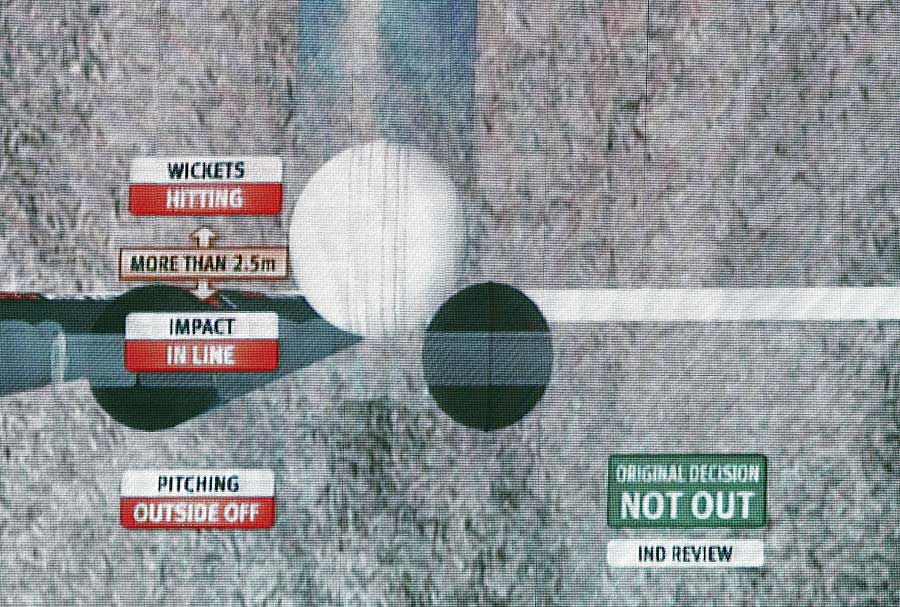

The new lbw law should simply say: "Any delivery that strikes the pad without first hitting the bat and, in the umpire's opinion, would go on to hit the stumps is out regardless of whether or not a shot is attempted."

Forget where the ball pitches and whether it strikes the pad outside the line or not; if it's going to hit the stumps, it's out.

There will be screams of horror - particularly from pampered batsmen - but there are numerous positives this change would bring to the game. Most important is fairness. If a bowler is prepared to attack the stumps regularly, the batsman should only be able to protect his wicket with the bat. The pads are there to save the batsman from injury not dismissal.

---Also read

---

It would also force batsmen to seek an attacking method to combat a wristspinner pitching in the rough outside the right-hander's leg stump.

Contrast Sachin Tendulkar's aggressive and successful approach to Shane Warne coming round the wicket in Chennai in 1997-98 with a batsman who kicks away deliveries pitching in the rough and turning in toward the stumps. Which would you rather watch?

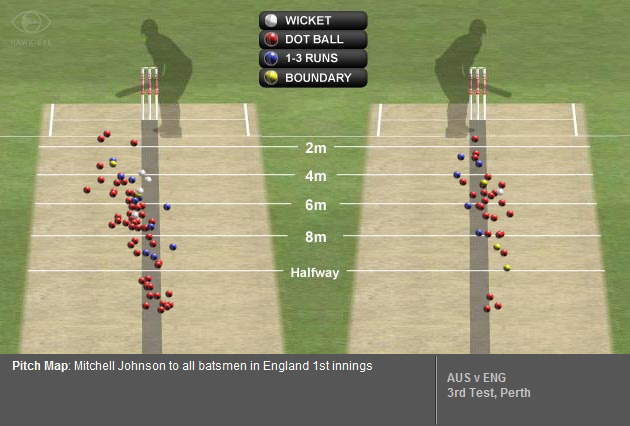

The current law encourages "pad play" to balls pitching outside leg while this change would force them to use their bat. The change would reward bowlers who attack the stumps and decrease the need for negative wide deliveries to a packed off-side field.

The law, as it pertains to pitching outside leg, was originally introduced to stop negative tactics to slow the scoring. Imagine trying to stifle players like VVS Laxman and Mark Waugh by bowling at their pads. The law should retain the current clause where negative bowling down the leg side is deemed illegal.

This change to the lbw law would also simplify umpiring and result in fewer frivolous DRS challenges. Consequently, it would speed up a game that has slowed drastically in recent times. It would also make four-day Tests an even more viable proposition as mind-numbing huge first-innings totals would be virtually non-existent.

The priority for cricket administrators should be to maintain an even balance between bat and ball. These law changes would help redress any imbalance and make the game, particularly Test cricket, a far more entertaining spectacle.

It would also force batsmen to seek an attacking method to combat a wristspinner pitching in the rough outside the right-hander's leg stump.

Contrast Sachin Tendulkar's aggressive and successful approach to Shane Warne coming round the wicket in Chennai in 1997-98 with a batsman who kicks away deliveries pitching in the rough and turning in toward the stumps. Which would you rather watch?

The current law encourages "pad play" to balls pitching outside leg while this change would force them to use their bat. The change would reward bowlers who attack the stumps and decrease the need for negative wide deliveries to a packed off-side field.

The law, as it pertains to pitching outside leg, was originally introduced to stop negative tactics to slow the scoring. Imagine trying to stifle players like VVS Laxman and Mark Waugh by bowling at their pads. The law should retain the current clause where negative bowling down the leg side is deemed illegal.

This change to the lbw law would also simplify umpiring and result in fewer frivolous DRS challenges. Consequently, it would speed up a game that has slowed drastically in recent times. It would also make four-day Tests an even more viable proposition as mind-numbing huge first-innings totals would be virtually non-existent.

The priority for cricket administrators should be to maintain an even balance between bat and ball. These law changes would help redress any imbalance and make the game, particularly Test cricket, a far more entertaining spectacle.