I don't trust the data. Don't worry, this isn't another Peter Moores thinkpiece. It's Hawk-Eye or ball-tracker or whatever you want to call it. I don't trust it. I don't trust the readings it gives.

This isn't a flat-earth theory, though flat earth does come into it, I suppose. How on earth can six cameras really predict the movement of a ball (a non-perfect sphere prone to going out of shape at that) on a surface that is neither flat nor stable? A ball that's imparted with constantly changing amounts of torque, grip, flight, speed and spin, not to mention moisture.

----- Also Read

------

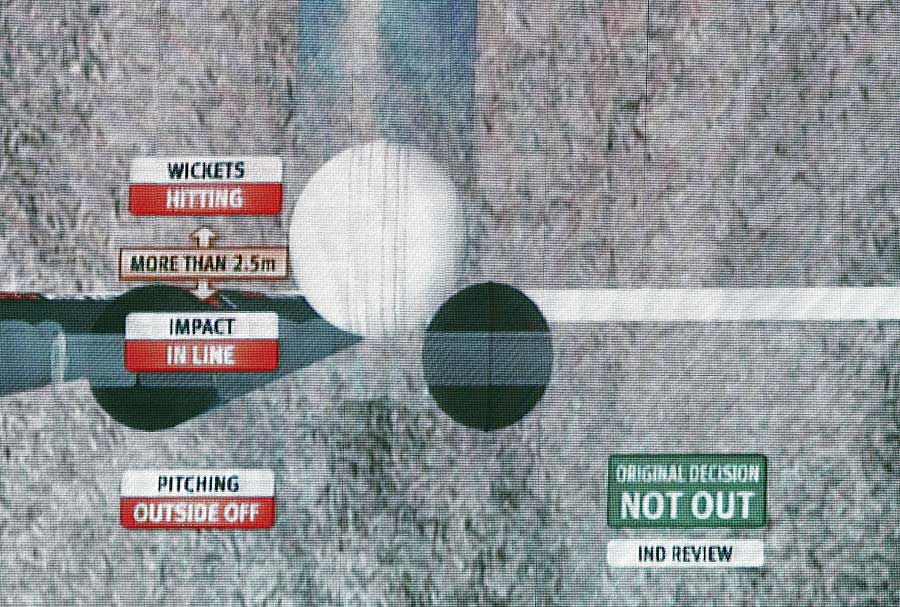

When Hawk-Eye, a prediction system with a known and well-publicised propensity for minor error (2.2 millimetres is the most recent publicly available figure) shows a fraction less than a half of the ball clipping leg stump after an lbw appeal, can we take that information on face value and make a decision based upon it?

During Tuesday's World Cup semi-final, my long-held conspiracy theory bubbled over. How, I wondered, could the ball that Imran Tahir bowled to Martin Guptill in the sixth over - the turned-down lbw shout from which the bowler called for a review - have passed as far above the stumps as the TV ball-tracker indicated? To the naked eye it looked wrong. The predicted bounce on the Hawk-Eye reading looked far too extravagant.

Worse, why upon seeing that projection did every single person in the pub I was in "ooh" and "aah" as though what they were seeing was as definitive and irrefutable an event as a ball sticking in a fieldsman's hands, or the literal rattle of ball on stumps? Have we just completely stopped questioning the authority of the technology and the data?

Later I checked the ball-by-ball commentary on ESPNcricinfo. Here's what it said: "This is a flighted legbreak, he looks to sweep it, and is beaten. Umpire Rod Tucker thinks it might be turning past the off stump. This has pitched leg, turned past the bat, hit him in front of middle, but is bouncing over, according to the Hawkeye. That has surprised everybody. That height has come into play here. It stays not-out."

It surprised me, but did it surprise everybody? Probably not. More TV viewers seemed to accept the call than question it. When you've watched enough cricket though, some things just look a little off. To me this one didn't add up. Guptill made another 28 runs, not a trifling matter in the context of the game.

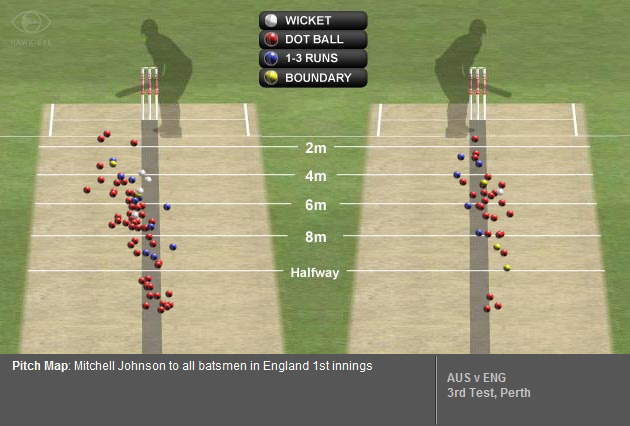

A disclaimer: though I distrust it for lbw decisions, I'm not saying that Hawk-Eye is all bad. It's great for "grouping" maps to show you where certain bowlers are pitching the ball, because tracking where a ball lands is simple. What happens next I'm not so sure on, particularly when the spinners are bowling.

To be fair, Hawk-Eye's inventor Paul Hawkins was a true pioneer and has arguably made a greater contribution to the entertainment factor of watching cricket on TV than many actual players manage. That's the thing though: it's entertainment. In 2001, barely two years after Hawkins had developed the idea it had won a BAFTA for its use in Channel 4's Ashes coverage that year. It wasn't until 2008 - seven years later - that it was added as a component of the Decision Review System. Quite a lag, that.

On their website, admittedly not the place to look for frank and fearless appraisal of the technology, Hawk-Eye (now owned by Sony) claim that the fact TV viewers now expect a reading on every lbw shout is "a testimony to Hawk-Eye's reputation for accuracy and reliability". But it's not, is it? All that it really tells us is that we are lemmings who have been conditioned to accept the reading as irrefutable fact upon which an umpiring decision can be made. But it's a prediction.

Not even Hawk-Eye themselves would call it a faultless system. Last December the company admitted they had got a reading completely wrongwhen Pakistan's Shan Masood was dismissed by Trent Boult during the Dubai Test. In this instance, the use of only four cameras at the ground (Hawk-Eye requires six) resulted in the operator making an input error. Why it was even being used under those conditions is more a question for the ICC, I suppose.

The Masood debacle highlights an interesting issue with regards to the cameras though. Understandably given the pay cheques at stake and that Hawk-Eye is a valuable component of their coverage, TV commentators rarely question the readings even in cases as puzzling as the Masood verdict. Mike Haysman is one who stuck his neck out in a 2011 Supersport article. Firstly, Haysman echoed my earlier thought: "The entertainment factor was the exact reason they were originally introduced. Precise decision-making was not part of the initial creative masterplan." The technology has doubtless improved since, but the point remains.

More worryingly though, Haysman shone a light on the issue with the cameras upon which Hawk-Eye depends. At that point an Ashes Test, for instance, might have had bestowed upon it a battalion of deluxe 250 frame-per-second cameras, whereas a so-called lesser fixture might use ones that captured as few as 25 frames-per-second. Remember: the higher the frame rate the more accurate the reading. Put plainly, for the past five years the production budget of the rights holder for any given game, as well as that game's level of perceived importance, has had an impact on the reliability of Hawk-Eye readings. Absurd.

As a general rule, the more you research the technology used in DRS calls, the more you worry. In one 2013 interview about his new goal-line technology for football, Paul Hawkins decried the lack of testing the ICC had done to verify the accuracy of DRS technologies. "What cricket hasn't done as much as other sports is test anything," he started. "This [football's Goal Decision System] has been very, very heavily tested whereas cricket's hasn't really undergone any testing." Any? Then this: "It's almost like it has tested it in live conditions so they are inheriting broadcast technology rather than developing officiating technology." Does that fill you with confidence?

Hawkins and science-minded cricket fans might bray at the suggestion that Hawk-Eye can't be taken as law, but in lieu of any explanation of its formulas, machinations and the way it's operated (also known as proprietary information) it's hard for some of us to shake the doubt that what we're seeing with our eyes differs significantly from the reading of a computer.

No comments:

Post a Comment