As George Osborne envisages a smaller state, economist Mariana Mazzucato argues instead that a programme of forward-thinking public spending is crucial for a creative, prosperous society. We must stop seeing the state as a malign influence or a waste of taxpayers' money

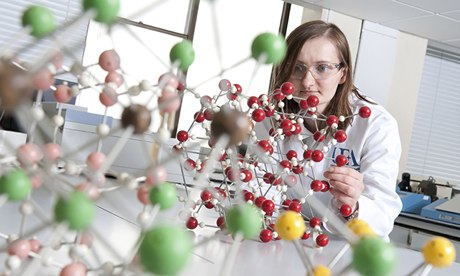

Bright spark: a government that ‘thinks big and makes things happen’ will also serrve as a catalyst to the private sector. Photograph: David Burton /Alamy

In his epic book, The End of Laissez-Faire (1926), John Maynard Keynes wrote a sentence that should be the guiding light for politicians around the globe. "The important thing for government is not to do things which individuals are doing already, and to do them a little better or a little worse; but to do those things which at present are not done at all."

In other words, the point of public policy is to make big things happen that would not have happened anyway. To do this, big budgets are not enough: big thinking and big brains are key.

While economists usually talk about things that are not done at all (or done inadequately) by the private sector as "public goods", investments in "big" public goods like the UK national health service, or the investments that led to new technologies behind putting a "man on the moon", required even more than fixing the "public good" problem. They required the willingness and ability to dream up big "missions". The current narrative we are being sold about the state as a "meddler" in capitalism is putting not only these missions under threat, but even more narrowly defined public goods.

Public goods are goods whose benefits are spread so widely that it is hard for business to profit from them (or stop others profiting from them). So they don't attract private investment. Examples include transport infrastructure, healthcare, research and education.

Even if you're an avid free-marketeer you can't avoid benefiting, directly and indirectly, from such public investments. You gain directly through the roads you drive down, the rules and policing which ensure their safety, the BBC radio you listen to, schools and universities that train the doctors and pilots you depend on, parks, theatre, films and museums that nurture our national identity. You also gain, indirectly, through enormous public subsidies without which private schools, hospitals and utility providers would never be able to deliver affordably and still make a profit. These are conferred as tax breaks, and provision of vital skills and infrastructure at state expense.

While social welfare is relentlessly trimmed and targeted, corporate welfare grows inexorably, as business widens its relief from the taxes that fund public infrastructure (while tax credits top-up its less generous wage packets). And the non-appropriable benefits of knowledge – costly to produce, cheap to acquire and use once published – spread the influence of public goods much wider. Nuclear fusion, fuel cells, asset-pricing formulas and genome maps are discoveries for all, not just one company. But it now seems like the doubters, those who contest the idea of "public goods", have won the contest. The state's provision of many of these goods – notably transport, education, housing and healthcare – is being privatised or outsourced at an increasing rate. Indeed privatisation and outsourcing are happening at such a rapid pace in the UK they are practically being given away – as the sale of Royal Mail at rock bottom prices revealed recently – denying the state a return for its near-century long investment.

Yet because we are told the state is simply a "spender" and meddling "regulator", and not a key investor in valuable goods and services, it is easier to deny the state a return from its investment: risk is socialised, rewards privatised. This not only eliminates any return on public investment but also destroys institutions that have taken decades to build up, and rapidly erodes any idea of public service distinct from private profit.

When public goods are privatised they lose their "public good" nature: it does become possible to profit from distributing mail, running trains, renting out homes and providing education. We're continually promised that, due to efficiency gains and innovations prompted by the profit motive, public goods can be delivered more cheaply and effectively by the private sector. All this while still giving their providers a decent profit, so that more is invested.

Has privatisation of UK rail provided lower prices, more innovation and investment? Has contracting-out prison security to G4S made that system more efficient and high quality? Have outsourced NHS services provided the taxpayer with higher quality healthcare that's still free of charge and assigned on merit? Users' impressions and regulators' performance indicators give at best a mixed signal on service quality. Private firms' commercial confidentiality – often a stark contrast with the right-to-know approach to public enterprise – makes it hard to identify or measure any changes in efficiency.

So the state is robbed of its deserved returns of investment, and public services are worsening – but is the state at least relieved of the associated costs and financial burden? No. What's very clear is that while private profits are now being made, public subsidy has not disappeared. The UK government explicitly subsidises its "privatised" utilities, with net transfers amounting to (among others) more than £2bn annually for train operating companies, and £10bn in investment guarantees alone for new nuclear power station builders (these, ironically, include other countries' state-owned utility firms – willing to advance their capital under the generous long-term price arrangements offered by the government, while their privatised UK counterparts like Centrica dismiss these as too risky and return their cash to shareholders).

Private companies can receive further implicit subsidies through investment guarantees and tax breaks; ad hoc assistance (such as meeting energy firms' decommissioning costs, and taking over pension liabilities to enable privatisation, as with Royal Mail and the remnants of the coal industry); rules that enable the circumvention of corporate taxes that are already below income-tax rates (and falling fast); and the assurance that the state will step back in to repossess (without penalty) any operations the private sector finds too expensive, as with Network Rail and the East Coast train-operating franchise.

But in the US, UK and all across Europe, where it's almost universally argued that today's governments are too big, these subsidies are rarely called into question. The debate focuses on the need for public debt levels to come down. And since taxes are judged to be too high – on the basis of very unclear arguments regarding incentives – debt reduction ends up relying on massive public-spending cuts. Growth will supposedly be stimulated by reducing the size of the public sector though privatisation and outsourcing – alongside the eternally-promised reduction of tax and "red tape", which is seen to be hindering an otherwise dynamic private sector.

Typically, the last UK budget focused on targeted tax reductions which are more fairly termed "tax expenditures", lifting a "burden" from companies that other sectors (mainly public services) will have to absorb. These include a drop in corporation tax to 20% from April 2015 (explicitly designed to undercut the rest of the G20), more reliefs from national insurance, and reductions in regulation – always hailed as reducing cost, despite the financial sector's recent warning on where those short-term savings can later lead.

Is tax too high? In the US, the top marginal income tax rate was close to 90% under Republican president Dwight Eisenhower – widely recognised as reigning over one of the highest growth periods in US history. Today the total US tax bill is the lowest it has ever been. The spending cuts about to hit the US – the infamous "sequester", which will damage institutions ranging from Nasa to social services – would not be needed if the US tax bill (24.8% of GDP) were only four percentage points lower than the OECD average (33.4%), instead of eight points.

Yet tax cuts usually achieve no discernible increase in investment, only a measurable increase in inequality. This is because what actually guides business investment is not the "bottom line" (costs, as affected by tax) but anticipation of where the future big technological and market opportunities are.

In the UK, Pfizer did not move its largest R&D lab in Sandwich, Kent to Boston due to lower tax or regulation but due to the £32bn a year that the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) spends on the bio-medical knowledge base that feeds them. Equally, although it was the National Venture Capital Association that in the mid-1970s negotiated huge reductions in US capital gains tax (from 40% to 20% in just six years), venture capital was actually following the footsteps of strategic public funding. In biotech, it entered the game 15 years after the state did the hard stuff.

And when the UK's Labour government reduced the minimum time for private equity investment to qualify for similar tax breaks from 10 to two years,it made venture capital even more short-termist, increasing golfing time not investing time. For the private sector, opportunities lie not in the creation of major new knowledge and technology but in the returns on investment in "intellectual property" that others have commissioned and not yet commercialised. Profit flows from privately capturing the "external benefits" conferred by public goods, when the public sector continues to underwrite them

The challenge today is to bring back knowledge and expertise into government that can drive the big missions of the future. Yet current de-skilling and de-capacitating government will not allow that. As I discuss in my new book, The Entrepreneurial State:debunking private vs. public sector myths, all the technologies that make the iPhone so smart were indeed pioneered by a well-funded US government: the internet, GPS, touch-screen display, and even the latest Siri voice-activated personal assistant.

All of these came out of agencies that were driven by missions, mainly around security – and funding not only the upstream "public good" research but also applied research and early-stage funding for companies. New missions today should be expanded around problems posed by climate change, ageing, inequality and youth unemployment. But while it's great that Steve Jobs had the genius to put those government technologies into a well-designed gadget, and great, more generally, for entrepreneurs to surf this publicly funded wave, who will fund the next wave with starved public budgets and a financialised and tax-avoiding private sector?

As the late historian Tony Judt used to stress, we should invent and impose a new narrative and new terminology to describe the role of government. The language being used to describe government activity is illuminating. The recent RBS sale was depicted as government retaining the "bad" debt, and selling the "good" debt to the private sector. The contrast could not be starker: bad government, good business – a needless inversion of the public good.

And public investments in long-term areas like R&D are described as government only "de-risking" the private sector, when actually what it is doing is actively and courageously taking on the risk precisely where the private sector – increasingly more concerned with the price of stock options than long-run growth opportunities – is too scared to tread. Once the entrepreneurial and risk-taking role of government is admitted, this should result in a sharing of the rewards – whether through equity of retaining a golden share of the patent rights. By privatising public goods, outsourcing government functions, and the constant state bashing (government as "meddler", at best "de-risker") we are inevitably killing the ability of government to think big and make things happen that otherwise would not have happened. The state starts to lose its capabilities, capacity, knowledge and expertise.

Examples that counter this trend – and language – should be celebrated. When the BBC invested in iPlayer – the world's most innovative platform for online broadcasting – instead of outsourcing it, it went against the grain. It brought brains and knowledge into a public sector institution. When recently the Government Digital Services (GDS) – part of the UK's Cabinet Office – wanted to create its own website, the usual solution was to outsource it to Serco, a private company that has recently won many government contracts (even Obamacare insurance work).

Dissatisfied with the mediocre site that Serco offered, GDS brought in coders and engineers with iPlayer experience, who went on to produce an award-winning websitethat is costing the government a fraction of what Serco was charging. And in so doing also made government smarter – attracting, not haemorrhaging, the knowledge and capabilities required for dreaming up the missions of the future.

To foster growth we must not downsize the state but rethink it. That means developing, not axing, competences and dynamism in the public sector. When evaluating its performance, we must rediscover the point of the public sector: to make things happen that would not have happened anyway.

When the BBC is accused of "crowding out" private broadcasters, the difference in quality of the programmes is considered a subjective issue not worthy of economic analysis. Yet it is only by observing and measuring that difference that we can accurately judge its performance. The same is true for the ability of public sector institutions not only to subsidise pharmaceutical companies but actually to transform the technological and market landscape on which they operate.

The public sector must produce public goods, and through the creation of new missions catalyse investment by the private sector – inspiring and supporting it to enter in high-risk areas it would not normally approach. To do so it requires the ability to attract top expertise – to "pick" broadly defined directions, as IT and internet were picked in the past, and "green" should be picked in the future. Some investments will win, some will fail. Indeed, Obama's recent $500m guaranteed loan to a solar company Solyndra failed, while the same investment in Tesla's electric motor won big time – making Elon Muskricher.

But as long as we admit the state is a risk-taking courageous investor in the areas the private sector avoids, it should increase its courage by earning back a reward for such successes, which can fund not only the (inevitable) losses but also the next round of investments. Instead, calling it names for the losses, ignoring the wins, and outsourcing the competence and capabilities, is ridding it of the courage, ability and brains to create the missions, hence opportunities, of the future. And without brains, all government will be able to do is not make big things happen but simply serve a private sector that is concerned only with serving itself.