'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label foundation. Show all posts

Showing posts with label foundation. Show all posts

Sunday, 3 December 2023

Thursday, 20 May 2021

How Sadhguru built his Isha empire. Illegally

Anish Daolagupu

Jaggi Vasudev, Anglophone India’s star godman, has challenged on more occasions than one that if the accusations of illegal deeds that have followed him around like ardent devotees were ever proved, he would quit India. The charges are legion, contained in testimonies of the allegedly wronged and tomes of government records. And there is much there, as Newslaundry found after examining a whole lot of them, to, at the very least, merit an investigation. Absent that, the accusations remain just that, accusations, merely a nuisance in his way as Vasudev goes about expanding his vast religio-cultural and business empire, the Isha Foundation. And, in the process, building himself up as arguably the country’s most influential godman.

But what precisely are the accusations against Vasudev, or Sadhguru as his devotees know him? Have they ever been investigated? If yes, what was the outcome? If no, why not? Did he use his godman persona and influence to indulge in illegalities or did the alleged illegalities enable his rise to fame and fortune?

To answer such questions, Newslaundry spoke with public servants, activists, and whistleblowers; trawled government records on the foundation; and examined court cases filed against them over the years and investigations conducted.

What we pieced together is really just the same old story of greed, corruption, and abuse of socio-religio-cultural sentiment for material enrichment. At the centre of this story is an Adivasi hamlet called Ikkarai Boluvampatti in Tamil Nadu’s Coimbatore.

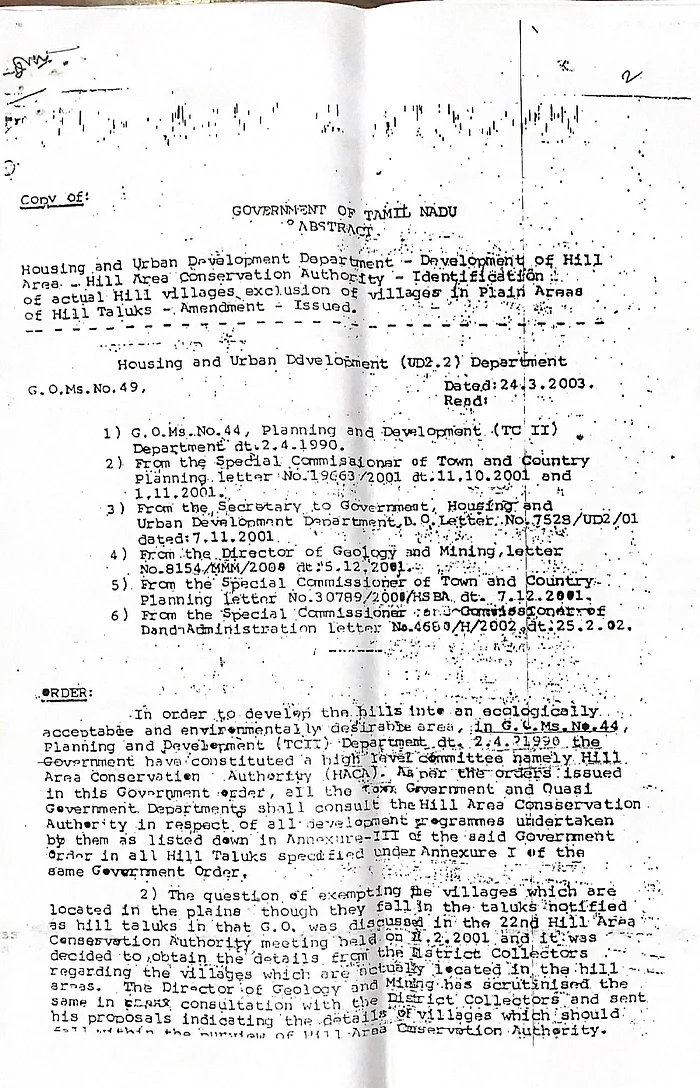

Ikkarai Boluvampatti, in the foothills of the Velliangiri hills, is where the Isha Foundation is headquartered on a sprawling 150-acre campus of 77 large and small structures, including the Isha ashram, built between 1994 and 2011 in blatant violation of laws and rules. The campus is adjacent to the Bolampatty Reserve Forest, an elephant habitat in the Nilgiris biosphere reserve, and along the Thanikandi-Marudhamalai migration corridor of the pachyderms. So, human activity, let alone construction, is regulated by the Hill Area Conservation Authority, or HACA, set up in 1990 to preserve wildlife and ecology of forested hill regions of Tamil Nadu.

Here, construction on over 300 sq metres of land can’t be done without HACA’s approval. Yet, records obtained by Newslaundry from the state departments of forest, town and country planning, and housing and urban development show that from 1994 to 2011, Isha constructed on 63,380 sq meters and created an artificial lake on another 1,406.62 sq metres at Ikkarai Boluvampatti, without approval. Vasudev and his foundation have said they got permission to build on about 32,855 sq metres from the local panchayat, but the rural body doesn’t have the power to authorise construction in areas under HACA.

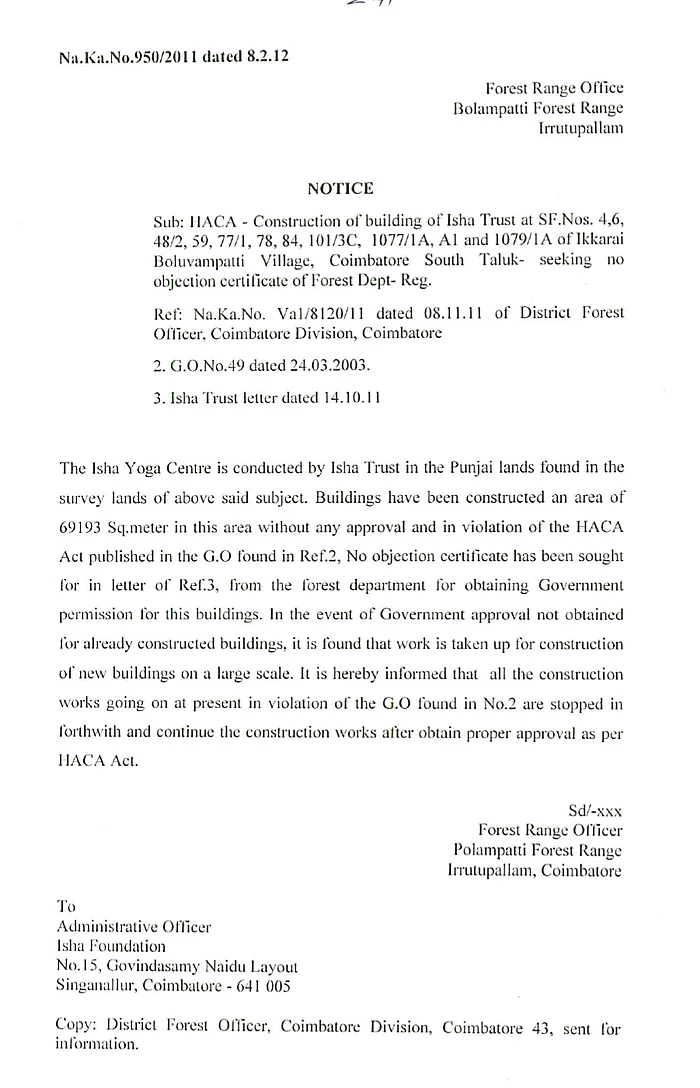

Isha did apply for approval from HACA in 2011, but after they had already built several structures. In July 2011, a forest department document shows, Isha asked HACA to greenlight illegal constructions on 63,380 sq meters as well as new constructions on 28582.52 sq metres. Taking up the application, V Thirunavukkarasu, then Coimbatore’s forest officer, visited the Isha ashram in February 2012. He found Isha had illegally constructed a series of buildings, including on the 28,582.52 sq meter plot for which it had gone to HACA for approval.

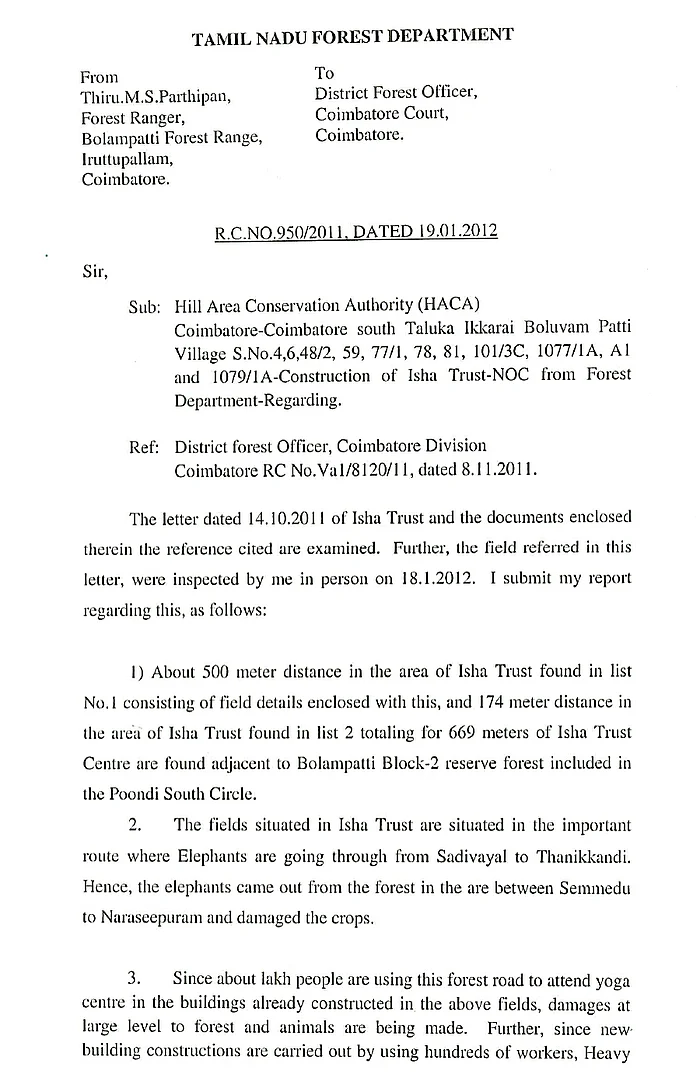

Thirunavukkarasu also found that the compound wall of the ashram and front gate were built from the forest land. Moreover, Isha’s many constructions and the resultant rush of visitors to the ashram had obstructed the elephant corridor, heightening man-animal conflict. So, he denied them approval. In October that year, Isha withdrew its application on the prexet of amending it. They didn’t file it again until 2014.

Thirunavukkarasu would return to Coimbatore as the chief conservator of forests in 2018, only to be moved out after just four days.

MS Parthipan, a forest ranger, too visited the Isha ashram in 2012. He found some of its lands fell on routes elephants used to move between Sadivayal and Thanikkandi. Since Isha had illegally erected buildings, walls and electric fences on these lands, elephants were forced to emerge from the forest between Semmedu and Narseepuram, trampling crops and attacking villagers.

“Any construction requiring over 300 sq meters of land requires HACA’s permission. Isha undertook construction without permission over a large area. They built structures first and then applied for approval. Whenever they did seek permission for new construction, they didn’t wait for our nod and simply started building,” a forest official who was privy to Parthipan’s inspection said on the condition of anonymity. “Isha’s lands were inside the elephant corridor and they were obstructing it, so they didn’t get clearance.”

Isha has marked at least 33 structures at the Ikkarai Boluvampatti campus for religious use which means they are considered public buildings under Tamil Nadu’s planning rules. Such structures require approvals from the district collector and the deputy director for town and country planning to build. Isha, records from the housing and urban development department show, didn’t bother taking these approvals.

Instead, they went to the panchayat, which isn’t empowered to grant such permissions without consulting the town and country planning department. The foundation did eventually go to the planning department for approval in 2011, but only after they had erected a series of structures – illegally. Aside from seeking approval for what they had built over the previous 15 years, the foundation asked the planning department for permission to construct 27 new buildings. The application, however, was incomplete and the department told them to file a new one by February 2012.

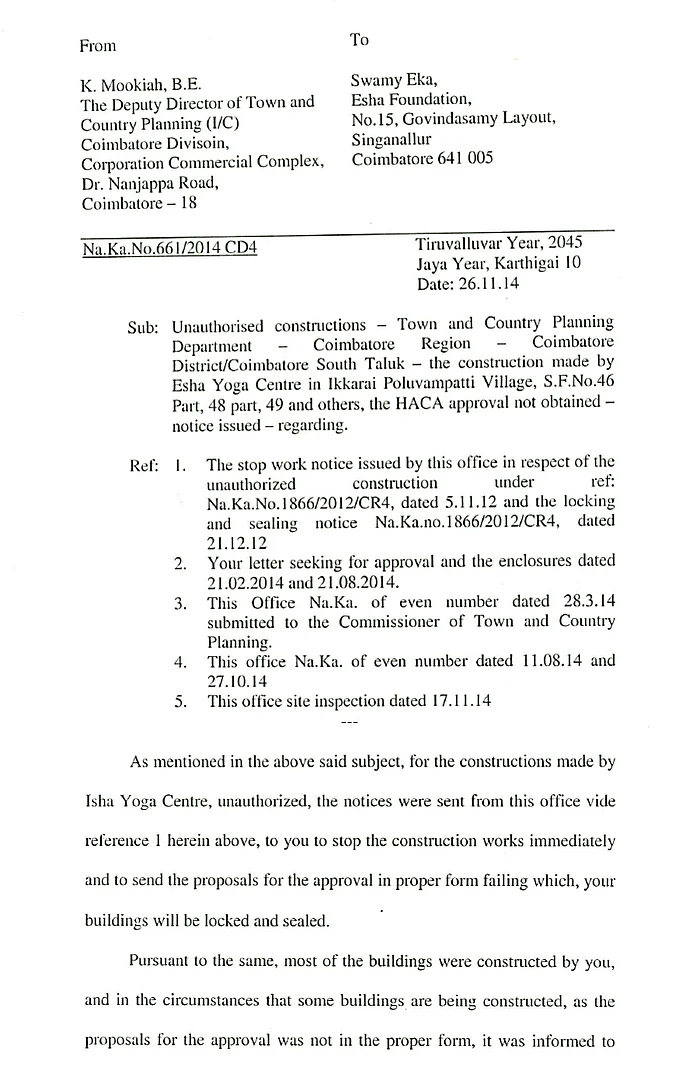

Isha breached the deadline and only sent a new application seven months later. Subsequently, when planning officials visited the ashram in October 2012 they found construction of the new buildings had already begun. They ordered the foundation to immediately stop all construction and followed up with a notice in November 2012. Isha didn’t care.

Finally, in December 2012, the planning department sent another notice directing Isha to demolish all illegal structures within a month. The foundation challenged the notice before the town and country planning commissioner. The matter is still hanging fire.

At the time, K Mookiah was deputy director, the town and country planning department, Coimbatore. Why did his department not act against Isha when they disregarded its orders? “After a month of issuing the notice I was transferred out,” he replied. “I don’t know what happened after that. I don’t know whether they have taken the approval or not.”

By 2012, Isha had constructed as many as 50 structures and was building 27 more, all illegally.

The foundation’s illegalities didn’t go unchallenged.

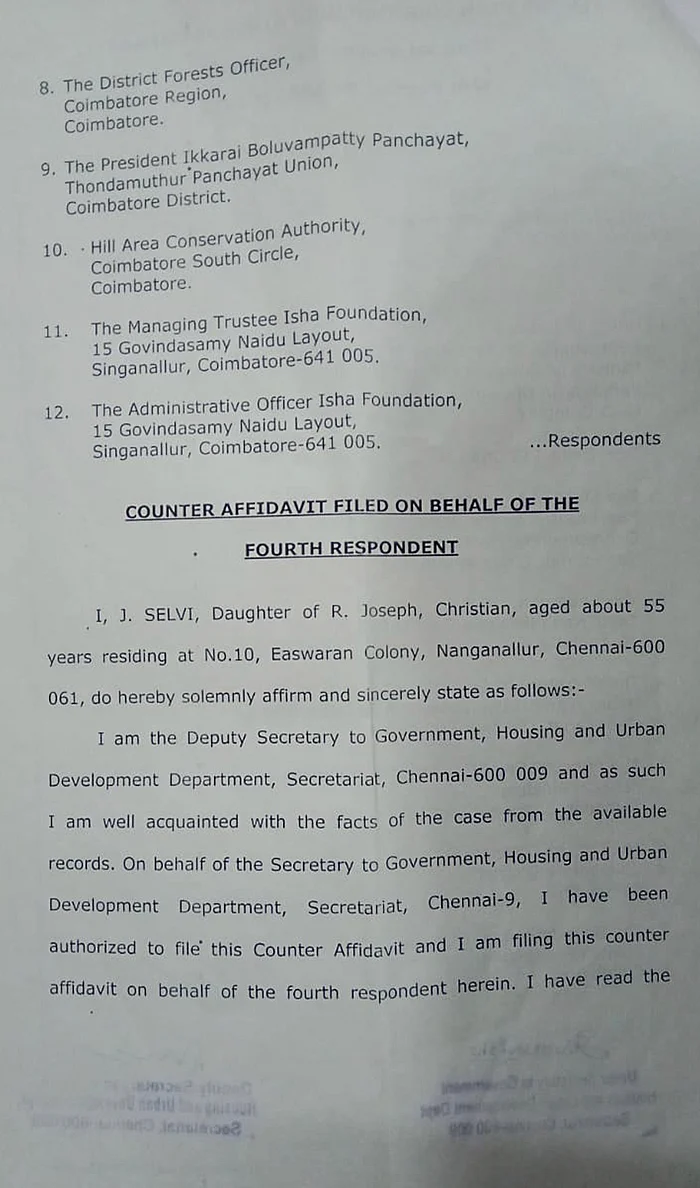

For the past eight years, M Vetri Selvan of the NGO Poovulagin Nanbargal has been fighting against Vasudev’s illegal constructions in the Madras high court, where he filed four petitions in 2013 and 2014. In his pleas, Selvan asked that the planning department’s order for demolition of Isha’s illegal structures be carried out, officials who had not acted against its illegalities be punished, Isha Sanskriti School’s illegal operation be stopped, and provision of cheap electricity to the Isha campus be stopped.

The pleas saw a total of 10 hearings from March 2013 to April 2014. And none since. “Our first petition regarding the demolition of Isha’s illegal construction was heard on March 8, 2013. A notice was issued to Isha, district collector, forest department, HACA, village panchayat. At the next hearing on March 25, 2013, Isha’s advocate sought time to file a counter.

On June 20, Isha, the planning department and the state government all filed their responses and the matter was adjourned. On August 22, 2013, we filed three more petitions and a combined hearing on all four pleas took place the next day. Both sides made arguments, but there was no reply from the state government and the matter was adjourned again,” he said. “At a hearing on March 13, 2014, the state school authority submitted that they hadn’t given Isha permission to run a school. After that, the court said the final hearing would happen once all the respondents had filed their counters. There has been no hearing since.”

In 2017, Selvan filed a petition against Isha’s Mahashivratri celebration, but the court didn’t entertain it because his previous pleas were still pending.

“The court also said I’d filed the petition with ulterior motive,” he added. “Man-animal conflict in and around the forests of Coimbatore has seen a spurt in the past 15-20 years. Primary reason is illegal construction in the elephant habitat, and Isha is involved on a wide scale. We are trying to save the natural environment of this area, to preserve its biodiversity. That’s why we are fighting against Isha’s illegal constructions. It’s not a personal feud.”

Isha's Adiyogi statue.

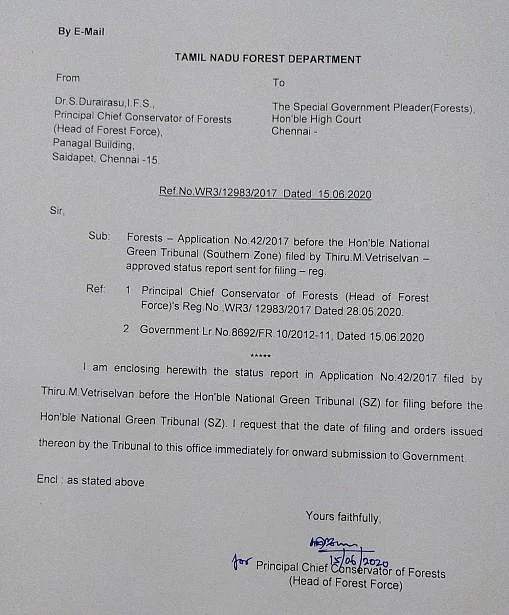

After he was turned away by the high court, Selvan went to the National Green Tribunal against Isha’s “destruction of environment and wildlife”. Three years later, the NGT directed Isha and the local administration to ensure big functions at the ashram such as the Mahashivratri celebration didn’t cause pollution.

Selvan wasn’t alone knocking the high court’s doors with a complaint against Isha in 2017. The Velliangiri Hill Tribal Protection Society also filed a plea, through P Muthammal, 49, an Adivasi from the Muttathu Ayal settlement in Ikkarai Boluvampatti.

Muthammal pleaded that rising man-animal conflict, for which Isha’s illegal constructions were mainly to blame, had made the lives of Adivasis difficult. He also objected to the foundation’s 112-foot Adiyogi statue, noting that it had been built without necessary clearances.

Replying to the petition, R Selvaraj, then deputy director, town and country planning, confirmed that the statue had been built without his department’s approval.

But by the time Selvaraj filed the reply, on February 28, 2017, the statue had already been inaugurated by none less than the prime minister.

That Modi didn’t hesitate to inaugurate the statue even though it was mired in a legal challenge was telling. A key reason Isha has got away with blatantly violating rules is that it has been enabled by political authorities, particularly the Tamil Nadu government.

Most blatantly, the forest department has dramatically changed its view that the Isha ashram is situated in the elephant corridor.

In 2012, records seen by Newslaundry show, Coimbatore’s forest officer told the state’s principal chief conservator of forests that Isha had built on land in the elephant corridor and its constructions and the rush of the devotees to the ashram – nearly two lakh on on Mahashivratri alone – had heightened man-animal conflict. Installation of powerful lights and high-decibel audio, not least for the Mahashivratri celebration, had only worsened the situation.

Similarly, a 2013 notification issued by the district collector stated in no uncertain terms, though without naming Isha, that illegal construction near the reserve forest in Ikkarai Boluvampatti was increasingly obstructing the corridor for elephants, causing the animals to damage life and property. The notice threatened to cut power, water ,sealing and demolition of the premises which had been built without HACA’s approval.

By 2020, however, the forest authorities were singing a discordant tune. In a June 2020 status report submitted to the National Green Tribunal, principal chief conservator of forests P Durairasu, claimed that the Isha campus was “adjacent” to the Ikkarai Boluvampatti Block 2 reserve forest, which was a “famous elephant habitat” but not a designated elephant corridor. For their yearly migration, he added, elephants passed near where the Isha ashram was situated in Ikkarai Boluvampatti but this spot wasn’t an authorised elephant corridor.

The swing in the forest department’s position on Ikkarai Boluvampatti would prove conveniently beneficial for Isha. In March last year, the EK Palaniswami government directed the regularisation of plots which have been built on without approval in the hill areas, including HACA lands that supposedly do not fall within the elephant corridor. They include Ikkarai Boluvampatti.

“We believe this rule has been brought to indirectly help the Isha Foundation regularise its illegal constructions,” claimed G Sundarrajan, an activist with the environmental advocacy group Poovulagin Nanbargal. “The government hasn’t yet notified they have made this rule.”

In 2017, after Isha had applied for HACA approval for constructions that they had already erected, H Basavraju, then the principal chief conservator, set up a committee to examine the submission. The committee found that Isha’s constructions were damaging to local wildlife and environment, and asked the district forest officer to recommend post-construction approval only if Isha made changes to the buildings, stopped using a few roads and agreed to not make any new construction within 100 metres of the forest reserve.

The same year, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India pulled up the state’s forest department for not stopping Isha’s illegal constructions despite knowing about them since 2012. The constructions had been done without required approvals from HACA, the CAG reiterated.

Responding to the CAG’s report, Isha claimed they have received HACA approval for all their constructions on March 16, 2017. But the committee formed by the principal chief conservator to inspect the Isha campus and decide on its application was formed only on March 17, and submitted its report on March 29. In fact, it wasn’t until April 4 that the principal chief conservator made a conditional recommendation to the town and country planning to grant post-construction approval to Isha. The planning department, in turn, directed its regional deputy director in Coimbatore on May 3 to issue post-construction to Isha provided they paid the required fees and adhered to the conditions of the forest department. How then is it possible for the HACA to have approved Isha’s constructions on March 16?

Isha refused to respond to this and other specific allegations. Replying to an email by Newslaundry seeking comment, a spokesperson for the foundation warned, “While your assumptions and presumptions are not material to us, should you slander the foundation, you will do so at your own risk.”

Tamil Nadu doesn’t have a mechanism to give post-construction clearance. The town and country planning department can regularise a construction post facto but only if its conditions are met. It can’t give an environmental clearance, however.

Basavraju, principal chief conservator at the time, wouldn’t answer our questions about recommending post-construction approval for Isha’s structures. His successor, Durairasu, who filed the status report to the National Green Tribunal, said, “Conditions were levied and then only recommendations were made. I don’t know whether they followed the conditions. As per my knowledge they have not received permission from HACA until now.”

Rajamani, who as Coimbatore’s district collector heads HACA, said he didn’t want to talk about the agency’s approval to Isha. “You can write whatever you want,” he added.

Thursday, 31 December 2015

What's the next generation of batsmen learning?

Ian Chappell in Cricinfo

It's now eight years since Misbah-ul-Haq's ill-conceived attempted scoop shot ballooned to short fine leg at the Wanderers Stadium and India were crowned inaugural World T20 champions.

Much has happened in cricket since that exciting five-run victory and the bulk of it revolves around the evolution of T20. Leagues have sprung up like daisies in summer, with the IPL being the most affluent and gaudy, whilst the other two versions of the game - Test and 50-over cricket - have receded into the shadows.

Now that kids from all over the world who watched that Wanderers final are at an age where they could make their own name in the game, it's time to look at how young players are being developed.

The dilemma involving the development of young cricketers is simple. For batsmen, it's: do you concentrate on a method that provides hitting power and the capability of scoring at ten runs per over, or do you develop a solid foundation that allows for adjustment to any form of the game?

For a bowler it's even more straightforward: do you implant in his mind a metronomic desire to produce a string of dot balls, or a mentality that stresses the priority of wickets?

Having just witnessed a 40-year-old Michael Hussey shred a Big Bash League attack with a mixture of scorching off-drives, gentle taps to initiate a scampered single and four power-laden shots that cleared the boundary, I'd opt for the solid foundation method.

Hussey, along with a number of other fine batsmen from an era when players were brought up with success in the longer forms of the game as a measuring stick, is proof a solid all-round technique is easily adaptable to T20 cricket. The best T20 teams have a combination of batsmen who can survive and prosper against good bowling and those who regularly clear the boundary rope.

The ideal fast bowling blueprint is Dale Steyn, a bowler who combines an excellent strike rate with a relatively low economy rate. For spinners, R Ashwin is a good role model; he takes wickets at both ends of the batting order and keeps the long balls to a minimum.

The secret to good bowling is to keep believing you can dismiss a batsman. Once that thought turns to purely containment, the batsman is winning the battle.

Given reasonable pitches, the bowlers adapt well, but many batsmen struggle in anything other than serene conditions. On the evidence of the eye test and the average length of a Test, it's obvious that solid foundations are crumbling and most batsmen are ill-equipped to survive a searching test by a good bowler. This has been a recent trend but I don't see any attempt to alter the way batsmen are being developed.

I suspect batsmen are being over-coached and bombarded with theories in structured net sessions that often involve the dreaded bowling machine. There's a lot to be said for the old-fashioned method of simply advocating a solid defence and then encouraging a youngster to spend hours playing in match situations - either in the backyard or at the local park - in order to learn how his own game works best.

This method worked extremely well for batsmen as successful and diverse in style as Sir Garfield Sobers, Sachin Tendulkar and Greg Chappell. As Sobers says in his excellent coaching book: "One of the tragedies of cricket coaching is the greatness of the game's best players is revered but never followed."

It would be a good start for a budding young batsman to emulate the style and development process of a Tendulkar, a Hussey or an AB de Villiers. It would also help if the youngster avoided listening to coaches with theories on batting that haven't been proven in the middle. As former great Australian legspinner Bill O'Reilly once stated: "If you see a coach coming, son, run and hide behind a tree."

I'd modify that for a young batsman and say: "Seek good coaching or else avoid it at all costs and learn the game for yourself."

It's now eight years since Misbah-ul-Haq's ill-conceived attempted scoop shot ballooned to short fine leg at the Wanderers Stadium and India were crowned inaugural World T20 champions.

Much has happened in cricket since that exciting five-run victory and the bulk of it revolves around the evolution of T20. Leagues have sprung up like daisies in summer, with the IPL being the most affluent and gaudy, whilst the other two versions of the game - Test and 50-over cricket - have receded into the shadows.

Now that kids from all over the world who watched that Wanderers final are at an age where they could make their own name in the game, it's time to look at how young players are being developed.

The dilemma involving the development of young cricketers is simple. For batsmen, it's: do you concentrate on a method that provides hitting power and the capability of scoring at ten runs per over, or do you develop a solid foundation that allows for adjustment to any form of the game?

For a bowler it's even more straightforward: do you implant in his mind a metronomic desire to produce a string of dot balls, or a mentality that stresses the priority of wickets?

Having just witnessed a 40-year-old Michael Hussey shred a Big Bash League attack with a mixture of scorching off-drives, gentle taps to initiate a scampered single and four power-laden shots that cleared the boundary, I'd opt for the solid foundation method.

Hussey, along with a number of other fine batsmen from an era when players were brought up with success in the longer forms of the game as a measuring stick, is proof a solid all-round technique is easily adaptable to T20 cricket. The best T20 teams have a combination of batsmen who can survive and prosper against good bowling and those who regularly clear the boundary rope.

The ideal fast bowling blueprint is Dale Steyn, a bowler who combines an excellent strike rate with a relatively low economy rate. For spinners, R Ashwin is a good role model; he takes wickets at both ends of the batting order and keeps the long balls to a minimum.

The secret to good bowling is to keep believing you can dismiss a batsman. Once that thought turns to purely containment, the batsman is winning the battle.

Given reasonable pitches, the bowlers adapt well, but many batsmen struggle in anything other than serene conditions. On the evidence of the eye test and the average length of a Test, it's obvious that solid foundations are crumbling and most batsmen are ill-equipped to survive a searching test by a good bowler. This has been a recent trend but I don't see any attempt to alter the way batsmen are being developed.

I suspect batsmen are being over-coached and bombarded with theories in structured net sessions that often involve the dreaded bowling machine. There's a lot to be said for the old-fashioned method of simply advocating a solid defence and then encouraging a youngster to spend hours playing in match situations - either in the backyard or at the local park - in order to learn how his own game works best.

This method worked extremely well for batsmen as successful and diverse in style as Sir Garfield Sobers, Sachin Tendulkar and Greg Chappell. As Sobers says in his excellent coaching book: "One of the tragedies of cricket coaching is the greatness of the game's best players is revered but never followed."

It would be a good start for a budding young batsman to emulate the style and development process of a Tendulkar, a Hussey or an AB de Villiers. It would also help if the youngster avoided listening to coaches with theories on batting that haven't been proven in the middle. As former great Australian legspinner Bill O'Reilly once stated: "If you see a coach coming, son, run and hide behind a tree."

I'd modify that for a young batsman and say: "Seek good coaching or else avoid it at all costs and learn the game for yourself."

Tuesday, 5 March 2013

A Capitalist Command Economy

With threats and bribes, Gove forces schools to accept his phoney 'freedom'

Through its academies programme, the government is creating a novelty: the first capitalist command economy

Illustration by Daniel Pudles

So much for all those treasured Tory principles. Choice, freedom, competition, austerity: as soon as they conflict with the demands of the corporate elite, they drift into the blue yonder like thistledown.

This is a story about England's schools, but it could just as well describe the razing of state provision throughout the world. In the name of freedom, public assets are being forcibly removed from popular control and handed to unelected oligarchs.

All over England, schools are being obliged to become academies: supposedly autonomous bodies which are often "sponsored" (the government's euphemism for controlled) by foundations established by exceedingly rich people. The break-up of the education system in this country, like the dismantling of the NHS, reflects no widespread public demand. It is imposed, through threats, bribes and fake consultations, from on high.

The published rules looked straightforward: schools will be forced to become academies only when they are "below the floor standard ... seriously failing, or unable to improve their results". All others would be given a choice. But in many parts of the country, schools which suffer from none of these problems are being prised out of the control of elected councils and into the hands of central government and private sponsors.

For five years, until 2012, Roke primary school in Croydon, south London, was rated as "outstanding" by the government's inspection service, Ofsted. Then two temporary problems arose. Several of the senior staff retired, leading to a short period of disruption, and a computer failure caused a delay in giving the inspectors the data they wanted. The school was handed the black spot: a Notice to Improve. It worked furiously to meet the necessary standards – and it has now succeeded. But before the inspection service returned to see whether progress had been made, the governors were instructed by the Department for Education to turn it into an academy.

In September last year the Department for Education held a closed meeting with the school's governors, in which they were told (according to the chair of the governors) that if they did not immediately accept its demand, "we will get the local authority to fire you, all of you ... if the local authority don't do it, we will. And we will put in our own interim board of governors, who will do what we say". The governors were instructed not to tell the parents about the meeting and their decision.

They did as they were told, partly because they had a sponsor in mind: the local secondary school, which had been helping Roke to raise its standards. They informed the department that this was their choice. It waited until the last day of term – 12 December – then let them know that it had rejected their proposal. The sponsor would be the Harris Federation. It was founded by Lord Harris, the chairman of the retail chain Carpetright. He is a friend of David Cameron's and one of the Conservative party's biggest donors.Roke will be the Harris Federation's 21st acquisition.

The parents knew nothing of this until 7 January, when 200 of them were informed at a meeting with the governors. They rejected the Harris Federation's sponsorship almost unanimously, in favour of a partnership with the local secondary school.

The local MP appealed to the schools minister Lord Nash, who happens to be another very rich businessman, major Tory donor and sponsor of academies. He replied last month: the decision is irreversible – Harris will run the school. But there will now be a "formal consultation" about it. He did not explain what the parents would be consulted about: the colour of the lampshades? Oh, and the body which will conduct the "consultation" is ... the Harris Federation. There is no mechanism for appeal. The parents feel they have been carpet-bombed.

Similar stories are being told up and down the country. Academy brokers hired by the department roam the land like medieval tax collectors, threatening and cajoling governors and head teachers, trying to force them into liaisons with corporate sponsors. Far from targeting failing schools, they often seem to pick on good schools that run into temporary difficulties. When standards rise again, the sponsors can take credit for it, and the "turnaround" can be claimed as another success. Ofsted is widely suspected of colluding in this process.

Where threats don't work, the department resorts to bribery. Schools are being offeredsweeteners of up to £65,000 of state money to convert. Vast resources are being poured by the education secretary, Michael Gove, into the academies programme, which has exceeded its budget by £1bn over the last two years. We are being pushed towards the policy buried on page 52 of the department's white paper: "it is our ambition that academy status should be the norm for all state schools".

Is this a prelude to privatisation? A leaked memo from the department recommends "reclassifying academies to the private sector". Just as Conservative health secretaries have done to the NHS, Michael Gove has published misleading statistics about our schools, to create the impression that they are failing by international standards. They are not.

Neither truth nor principle stands in the way of this demolition programme. All the promises of the market fundamentalists – choice, competitive tendering, decentralisation and savings – are abandoned in favour of brutal and extravagant dictat. Thus the government creates a novelty: a capitalist command economy.

Wednesday, 31 August 2011

This Jan Lokpal bill would increase the possibilities of the penetration of international capital in India - Arundhati Roy

In an exclusive interview, writer Arundhati Roy said there are serious concerns about the Jan Lokpal Bill, corporate funding, NGOs and even the role of the media.

Sagarika Ghose: Hello and welcome to the CNN-IBN special. The Anna Hazare anti-corruption movement has thrown up multiple voices. Many have been supportive of the movement, but there have been some who have been sceptical and raised doubts about the movement as well. One of these sceptical voices is writer Arundhati Roy who now joins us. Thanks very much indeed for joining us. In your article in 'The Hindu' published on August 21, entitled 'I'd rather not be Anna', you've raised many doubts about the Anna Hazare campaign. Now that the movement is over and the crowds have come and we've seen the massive size of those crowds, do you continue to be sceptical? And if so, why?

Arundhati Roy: Well, it's interesting that everybody seems to have gone away happy and everybody is claiming a massive victory. I'm kind of happy too, relieved I would say, mostly because I'm extremely glad that the Jan Lokpal Bill didn't go through Parliament in its current form. Yes, I continue to be sceptical for a whole number of reasons. Primary among them is the legislation itself, which I think is a pretty dangerous piece of work. So what you had was this very general mobilisation about corruption, using people's anger, very real and valid anger against the system to push through this very specific legislation or to attempt to push through this very specific piece of legislation which is very, very regressive according to me. But my scepticism ranges through a whole host of issues which has to do with history, politics, culture, symbolism, all of it made me extremely uncomfortable. I also thought that it had the potential to turn from something inclusive of what was being marketed and touted and being inclusive to something very divisive and dangerous. So I'm quite happy that it's over for now.

Sagarika Ghose: Just to come back to your article. You said that Arvind Kejriwal and Manish Sisodia have received $ 400,000 from the Ford foundation. That was one of the reasons that you were sceptical about this movement. Why did you make it a point to put in the fact that Arvind Kejriwal is funded by the Ford foundation.

Arundhati Roy: Just in order to point to the fact, a short article can just indicate the fact that it is in some way an NGO driven movement by Kiran Bedi, Arvind Kejriwal, Sisodia, all these people run NGOs. Three of the core members are Magsaysay award winners which are endowed by Ford foundation and Feller. I wanted to point to the fact that what is it about these NGOs funded by World Bank and Bank of Ford, why are they participating in sort of mediating what public policy should be? I actually went to the World Bank site recently and found that the World Bank runs 600 anti-corruption programmes just in places like Africa. Why is the World Bank interested in anti-corruption? I looked at five of the major points they made and I thought it was remarkable if you let me read them out:

1) Increasing political accountability

2) Strengthening civil society participation

3) Creating a competitive private sector

4) Instituting restraints on power

5) Improving public sector management

So, it explained to me why in the World Bank, Ford foundation, these people are all involved in increasing the penetration of international capital and so it explains why at a time when we are also worried about corruption, the major parts of what corruption meant in terms of corporate corruption, in terms of how NGOs and corporations are taking over the traditional functions of the government, but that whole thing was left out, but this is copy book World Bank agenda. They may not have meant it, but that's what's going on and it worries me a lot. Certainly Anna Hazare was picked up and propped up a sort of saint of the masses, but he wasn't driving the movement, he wasn't the brains behind the movement. I think this is something very pertinent that we really need to worry about.

Sagarika Ghose: So you don't see this as a genuine people's movement. You see it as a movement led by rich NGOs, funded by the World Bank to make India more welcoming of international capital?

Arundhati Roy: Well, I mean they are not funded by the World Bank, the Ford foundation is a separate thing. But just that I wouldn't have been this uncomfortable if I saw it as a movement that took into account the anger from the 2G Scam, from the Bellary mining, from CWG and then said 'Let's take a good look at who is corrupt, what are the forces behind it', but no, this fits in to a certain kind of template altogether and that worries me. It's not that I'm saying they are corrupt or anything, but I just find it worrying. It's not the same thing as the Narmada movement, it's the same thing as a people's movement that's risen from the bottom. It's very much something that, surely lots of people joined it, all of them were not BJP, all of them were not middle-class, many of them came to a sort of reality show that was orchestrated by even a very campaigning media, but what was this bill about? This bill was very, very worrying to me.

Sagarika Ghose: We'll come to the bill in just a bit but before that I want to bring in another controversial statement in your article which has sparked a great deal of controversy among even your old associates Medha Patkar and Prashant Bhushan, where you said, 'Both the Maoists and Jan Lokpal Movement have one thing in common, they both seek the overthrow of the Indian state.' Why do you believe that the movement for the Jan Lokpal Bill is similar to the Maoist movement in seeking the overthrow of the Indian state?

Arundhati Roy: Well, let's separate the movement from the bill, as I said that I don't even believe that most people knew exactly what the provisions of the bill were, those who were part of the movement, very few in the media and on the ground. But if you study that bill carefully, you see the creation of a parallel oligarchy. You see that the Jan Lokpal itself, the ten people, the bench plus the chairman, they are selected by a pool of very elite people and they are elite people, I mean if you look at one of the phases which says the search committee, the committee which is going to shortlist the names of the people who will be chosen for the Jan Lokpal will shortlist from eminent individuals of such class of people whom they deem fit. So you create this panel from this pool, and then you have a bureaucracy which has policing powers, the power to tap your phones, the power to prosecute, the power to transfer, the power to judge, the power to do things which are really, and from the Prime Minister down to the bottom, it's really like a parallel power, which has lost the accountability, whatever little accountability a representative government might have, but I'm not one of those who is critiquing it from the point of view of say someone like Aruna Roy, who has a less draconian version of the bill, I'm talking about it from a different point of view altogether of firstly, the fact that we need to define what do we mean by corruption, and then what does it mean to those who are disempowered and disenfranchised to get two oligarchies instead of one raiding over them.

Sagarika Ghose: So do you believe that the leaders of this movement were misleading the crowds who came for the protest because they were not there simply as an anti-corruption movement, they were there to campaign for the Jan Lokpal Bill and if people knew what the Jan Lokpal Bill was all about, in your opinion, setting up this huge bureaucratic monster, many of those people might well have not come for the movement, so do you feel that the leaders were misleading the people?

Arundhati Roy: I can't say that they were deliberately misleading people because of course, that bill on the net, if anybody wanted to read it could read it. So I can't say that. But I think that the anger about corruption became so widespread and generalised that nobody looked at what, there was a sort of dissonance between the specific legislation and the anger that was bringing people there. So, you have a situation in which you have this powerful oligarchy with the powers of prosecution surveillance, policing. In the bill there's a small section which says budget, and the budget is 0.25 per cent of the Government of India's revenues, that works out to something like Rs 2000 crore. There's no break up, nobody is saying how many people will be employed, how are they going to be chosen so that they are not corrupt, you know, it's a sketch, it's a pretty terrifying sketch. It's not even a realised piece of legislation. I think that, in a way the best thing that could have happened has happened that you have the bill and you have other versions of the bill and you have the time to now look at it and see whatever, I just want to keep saying that I'm not, my position in all this is not to say we need policing and better law. I'm a person who's asking and has asked for many years for fundamental questions about injustice, which is why I keep saying let's talk about what we mean by corruption.

Sagarika Ghose: And you believe that the reason why this movement is misconceived is because it's centered around this Jan Lokpal Bill?

Arundhati Roy: Yes, not just that, I think centrally, that I was saying earlier, can we discuss what we mean by corruption. Is it just financial irregularity or is it the currency of social transaction in a very unequal society? So if you can give me 2 minutes, I'll tell you what I mean. For example, corruption, some people, poor people in villages have to pay bribes to get their ration cards, to get their NREGA dues from very powerful vested interests. Then you a middleclass, you have honest businessmen who cannot run an honest business because of all sorts of reasons, they are out there angry. You have a middleclass which actually bribes to buy itself scarce favours and on the top you have the corporations, the politicians looting millions and mines and so on. But you also have a huge number of people who are outside the legal framework because they don't have pattas, they live in slums, they don't have legal housing, they are selling their wares on redis, so they are illegal and in an anti-corruption law, an anti-corruption law is naturally sort of pinned to an accepted legality. So you can talk about the rule of law when all your laws are designed to perpetuate the inequality that exists in Indian society. If you're not going to question that, I'm really not someone who is that interested in the debate then.

Sagarika Ghose: So fundamentally it's about service delivery to the poorest of the poor, it's about ensuring justice to the poorest of the poor, without that a whole bureaucratic infrastructure is meaningless?

Arundhati Roy: Well Yes, but you know as I said in my article, supposing you're selling your samosas on a 'rehdi' (cart) in a city where only malls are legal, then you pay the local policemen, are you going to have to now pay to the Lokpal too? You know corruption is a very complicated issue.

Sagarika Ghose: But what about the provisions for the lower bureaucracy. The lower bureaucracy is going to be brought into the Lokpal, they're going to have a state level Lokayukta, so there is an attempt within the Lokpal Bill to go right down to the level of the poorest of the poor and then you can police even those functionaries who deal with the very poor. So don't you have hope that there, at least, it could be regularised because of this bill?

Arundhati Roy: I think that part of the bill will be interesting, I think it's very complicated because the troubles that are besetting our country today are not going to be solved by policing and by complaint booths alone. But, at the lower level, I think we have to come up with something where you can assure people that you're not going to set up another bureaucracy which is going to be equally corrupt. When you have one brother in BJP, one brother in Congress, one brother in police, one brother in Lokpal, I would like to see how that's going to be managed, this law is very sketchy about that.

Sagarika Ghose: But just to come back to the movement again, don't you think that the political class has become corrupt and has become venal and you have a movement like this it does function as a wake up call?

Arundhati Roy: To some extent yes, but I think by focusing on the political class and leaving out the corporations, the media that they own, the NGOs that are taking over, governmental functions like health, you know corporates are now dealing with what government used to deal with. Why are they left out? So I think a much more comprehensive view would have made me comfortable even though I keep saying that for me the real issue is what is it that has created a society in which 830 million people live on less than Rs 20 a day and you have more people and all of the poor countries of Africa put together.

Sagarika Ghose: So basically what you're saying is that laws are not the way to tackle corruption and to tackle injustice. It's not through laws, it's not through legal means, we have to do it through much more decentralisation of power, much more outreach at the lowest level?

Arundhati Roy: I think first you have to question the structure. You see if there is a structural inequality happening, and you are not questioning that, and you're in fact fighting for laws that make that structural inequality more official, we have a problem. To give an example, I was just on the Chhattisgarh-Andhra Pradesh border where the refugees from Operation Greenhunt have come out and underneath. So for them the issue is not whether Tata gave a bribe on his mining or Vedanta didn't give a bribe in his mining. The problem is that there is a huge problem in terms of how the mineral and water and forest wealth of India is being privatised, is being looted, even if it were non corrupt, there is a problem. So that's why we're just not coolly talking about Dantewada, there are many a places I mean what's happening in Posco, in Kalinganagar . So this is not battles against corruption. There's something very, very serious going on. None of these issues were raised or even alluded to somehow.

Sagarika Ghose: So basically what you're saying is that it is not the battle against corruption which is the primary battle, it's the battle for justice that has to be the primary battle in India. Just to come back to the point about the law, many have said that this is a process of pre-legislative consultation, that all over the world now civil society groups, I know you don't like that word, are co-operating with the government in law making and a movement like this institutionalises that, institutionalises civil society groups coming into the law making process. Doesn't that make you hopeful about this movement?

Arundhati Roy: In principal, yes, but when a movement like this which has been constructed in the way that it has, you can talk about, sort of calls itself the people or civil society and says that it's representing all of civil society. I would say there's a problem there and it depends on the law. So right now I think the good thing that has happened is that the Jan Lokpal Bill which probably has some provisions that will make it into the final law, is one of the many bills that will be debated. So, yes, that's a good thing. But if it had just gone through in this way, I wouldn't be saying yes, that's a good thing.

Sagarika Ghose: Let's talk about the media. You've been very critical about the media and the way the media, particularly broadcast media has covered this movement, do you believe that if the media had not given it this kind of time, this movement simply wouldn't have taken off? Do you believe that it's a media manufactured movement?

Arundhati Roy: Well, I'm not going to say that's entirely media manufactured. I think that was one of the big factors in it. There was also mobilisation from the BJP and the RSS, which they've admitted to. I think the media, I don't know when before campaigned for something in this way where every other kind of news was pushed out and for ten days, you had only this news. In this nation of one billion people, the media didn't find anything else to report and it campaigned, not everybody, but certainly certain major television channels campaigned and said they were campaigning, they said, 'We're the channel through whom Anna speaks to the people and so on. Now firstly to me that's a form of corruption in the first place where presumably, a broadcast licence as a news channel has to do with reporting news, not campaigning. But even if you are campaigning and the only reason that everybody was reporting it was TRP ratings, then why not just settle for pornography or sadomasochism or whatever gives good TRP ratings. How can news channels just abandon every other piece of news and just concentrate on this for 10 days? You know how much of spot ad costs on TV, what kind of a price would you put on this? Why was it doing this? Per se if media campaigns had to do with social justice, if the media spent 10 days campaigning on why more than a lakh farmers have committed suicide in this country, I'd be glad because I would say okay, this is the job of the media. It is like the old saying - to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted.

Sagarika Ghose: But don't you think one man taking on the might of the government is a big story and don't you think that that deserves to be covered?

Arundhati Roy: No, I don't. For all the sorts of reasons that I've said, it was one man trying to push through a regressive piece of legislation.

Sagarika Ghose: Let's come to the role of the RSS which you have also eluded to. You've spoken about the role of aggressive nationalism or Vande Mataram being chanted, of the RSS saying that we're involved in this particular movement, but then your old associates Prashant Bhushan and Medha Patkar are in this movement as well. Is it fair to completely dub this movement as an RSS Hindu right wing movement?

Arundhati Roy: I haven't done that though some people have. But I think it's an interesting question to talk about symbolism and this movement. For example, what is the history of Vande Mataram? Vande Mataram first occurred in this book by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee in 1882, it became a part of a sort of war cry at the time of partition of Bengal and since then, since in 1937 Tagore said it's a very unsuitable national anthem, very divisive, it's got a long communal history. So what does it mean when huge crowds are chanting that? When you take up the national flag, when you're fighting colonialism, it means one thing. When you're a supposedly free nation that national flag is always about exclusion and not inclusion. You took up that flag and the state was paralysed. A state which is not scared of slaughtering people in the dark, suddenly was paralysed. You talk about the fact that it was a non violent movement, yes, because the police were disarmed. They just were too scared to do anything. You had Bharat Mata's photo first and then it was replaced by Gandhi. You had people who were openly part of the Manovadi Krantikari Aandolan there. So you have this cocktail of very dangerous things going on, you had other kinds of symbolism. Imagine Gandhi going to a private hospital after his fast. A private hospital that symbolises the withdrawal of the state from healthcare for the poor. A private hospital where the doctors charge a lakh every time they inhale and exhale. The symbolisms were dangerous and if this movement had not ended in this way, it could have turned extremely dangerous. What you had was a lot of people, I'm not going to say they were only RSS, I'm not going to say they were only middle-class, I'm not going to say they were only urban. But yes, they were largely more well off than most people who have been struggling on the streets and facing bullets in this country for a long time. But in some odd way the victims and the perpetrators of corruption of the recipients of the fruits of modern development, they were all there together. There were contradictions that could not have been held together for much longer without them just tearing apart.

Sagarika Ghose: But weren't you impressed by the sheer size of the crowd? Weren't you impressed by the spontaneity of the crowd? The fact that people came out, they voiced their anger, they voiced their protest, surely it can't just all be boxed into one shade of opinion.

Arundhati Roy: Should I tell you something Sagarika? I have seen much larger crowds in Kashmir. I have seen much larger crowds even in Delhi. Nobody reported them. They were then only called 'traffic jam bana diya inhone'. I was not impressed by the size of the crowds apart from the fact that I'm not that kind of a person. I'm sure there were larger crowds chanting for the demolition of the Babri Masjid, would that be fine by us? It's not about numbers.

Sagarika Ghose: Is that how you see this movement? You see it as a kind of Ram Janmabhoomi Part 2?

Arundhati Roy: No, not at all. I've said what I feel. That would be stupid for me to say. But I see it as something potentially quite worrying, quite dangerous. So I think we all need to go back and think a lot about what was going on there and not come to easy conclusions and easy condemnations, I think we really need to think about what was going on there, how it was caused, how it happened, what are the good things, what are the bad things, some serious thinking. But certainly I'm not the kind of person who just goes and gets impressed by a crowd regardless of what it's saying, regardless of what it's chanting, regardless of what it's asking for.

Sagarika Ghose: But what about the persona of Anna Hazare? Many would say that he evoked a certain different era, he evoked the era of the freedom struggle, he is a simple Gandhian, he does lead a very austere life, he lives in a small room behind a temple and his persona of what he is evokes a certain moral power perhaps which is needed in an India which is facing a moral crisis.

Arundhati Roy: I think Anna Hazare was a sort of empty vessel in which you could pour whatever meaning you wanted to pour in, unlike someone like Gandhi who was very much his own man on the stage of the world. Anna Hazare certainly is his own man in his village, but here he was not in charge of what was going on. That was very evident. As for who he is and what his affiliations and antecedents have been, again I'm worried.

Sagarika Ghose: Why are you worried?

Arundhati Roy: Some of things that one has read and found out about, his attitude towards Harijans, that every village must have one 'chamaar' and one 'sunaar' and one 'kumhaar', that's gandhian in some ways, you know Gandhi had this very complicated and very problematic attitude to the caste system, anyone who knows about the debates between Gandhi and Ambedkar will tell you that. But what I'm saying is eventually we live in a very complicated society. You have a strong left edition which doesn't know what to do with the caste system. You have the Gandhians who are also very odd about the caste system. You have our deeply frightening communal politics, you have this whole new era of new liberalism and the penetration of international capital. This movement just did not know the beginning of its morals. It could have ended badly because nobody really, you know, you choose something like corruption, it's a pot into which everyone can piss, anti-left, pro-left, right, I mean, I was in Hyderabad, Jagan Mohan Reddy who was at that time being raided by the CBI was one of his great supporters. Naveen Patnaik…

Sagarika Ghose: But isn't that its strength? It's an inclusive agenda. Anti-corruption movement brings people in.

Arundhati Roy: It's a meaningless thing when you have highly corrupt corporations funding an anti-corruption movement, what does this mean? And trying to set up an oligarchy which actually neatens the messy business of democracy and representative democracy however bad it is. Certainly it's a comment on the fact that our country suffering from a failure of representative democracy, people don't believe that their politicians really represent them anymore, there isn't a single democratic institution that is accessible to ordinary people. So what you have is a solution which isn't going to address the problem.

Sagarika Ghose: So a corporate funded movement which seeks to lessen the power of the democratic state and seeks to reduce the power of the democratic state?

Arundhati Roy: I would say that this bill would increase the possibilities of the penetration of international capital which has led to a huge crisis in the first place in this country.

Sagarika Ghose: Just on a different note, what do you think of the fast-unto-death? Many have criticised it as a 'Brahamastra' which shouldn't be easily deployed in political agitations, Gandhi used it only as a last resort. What is your view of the hunger strike or the fast-unto-death?

Arundhati Roy: Look the whole world is full of people who are killing themselves, who are threatening to kill themselves in different ways. From a suicide bomber to the people who are immolating themselves on Telangana and all that. Frankly, I'm not one of those people who's going to stand and give a lecture about the constitutionality of resistance because I'm not that person. For me it's about what are you doing it for. That's my real question - what are you doing it for? Who are you doing it for? And why are you doing it? Other than that I think I personally believe that there are things going on in this world that you really need to stand up and resist in whatever way you can. But I'm not interested in a fast-unto-death for the Jan Lokpal Bill frankly.

Sagarika Ghose: So what is your solution then. How would you fight corruption?

Arundhati Roy: Sagarika, I'm telling you that corruption is not my big issue right now. I'm not a reformist person who will tell you how to cleanse the Indian state. I'm going on and on in all the 10 years that I've written about nuclear powers, about nuclear bombs, about big dams, about this particular model of development, about displacement, about land acquisition, about mining, about privatisation, these are the things I want to talk about. I'm not the doctor to tell the Indian state how to improve itself.

Sagarika Ghose: So corruption really does not concern you in that sense?

Arundhati Roy: No, it does, but not in this narrow way. I'm concerned about the absolutely disgusting inequality in the society that we live in.

Sagarika Ghose: And this movement has done nothing to touch that. What precedents has it set for protest movements in the future? Do you think this movement has set a precedent for protest movements in the future?

Arundhati Roy: For protest movements of the powerful, protests movements where the media is on your side, protests movements where the government is scared of you, protest movements where the police disarm themselves, how many movements are there going to be like that? I don't know. While you're talking about this, the army is getting ready to move into Central India to fight the poorest people in this country, and I can tell you they are not disarmed. So, I don't know what lessons you can draw from a protest movement that has privileges that no other protest movement I've ever known has had.

Sagarika Ghose: Just to re-emphasise the point about Medha Patkar and Prashant Bhushan, these are old time associates of yours in activism. They are deeply involved in this particular movement. How do you react to them being involved in this movement of which, you're so critical?

Arundhati Roy: With some dismay because Prashant is a very close friend of mine and I respect Medha a lot, but I think that their credibility has been cashed in on in some ways, but I feel bad that they are part of it.

Sagarika Ghose: You have voiced fears in your article as well that in some ways, this movement and this bill is an attempt to diminish the powers of the democratic government and to reduce the discretionary powers of the democratic government. So you feel that this is a corporate funded exercise to reduce the powers of the democratically elected government?

Arundhati Roy: Well not corporate funded, but there's a sort of IMF World Bank way of looking at it, fuelling this whole path because if you remember in the early 90s when they began on this path of liberalisation and privatisation. The government itself kept saying, 'Oh, we're so corrupt. We need a systemic change, we can't not be corrupt,' and that systemic change was privatisation. When privatisation has shown itself to be more corrupt than, I mean the levels of corruption have jumped so high, the solution is not systemic. It's either moral or it's more privatisation, more reforms. People are calling for the second round of reforms for the removal of the discretionary powers of the government. So I think that's a very interesting that you're not looking at it structurally, you're looking at it morally and you're trying to push whatever few controls there are or took the way once again for the penetration of international capital.

Sagarika Ghose: But people like Nandan Nilekani have argued this movement and this bill could stop reforms actually. It could actually put an end to the reforms process by instituting this big bureaucratic infrastructure - this inspector raj. But you don't go along with that. You believe that this is a way of taking the reforms agenda forward.

Arundhati Roy: I think it depends on who captures that bureaucracy. That's why I'm worried about this combination of sort of Ford funded NGO world and the RSS and that sort of world coming together in a kind of crossroads. Those two things are very frightening because you create a bureaucracy which can then be controlled, which has Rs 2000 crore or whatever, 0.25 per cent of the revenues of the Government of India at its disposal, policing powers, all of this. So it's a way of side-stepping the messy business of democracy.

Sagarika Ghose: That's interesting the combination of Ford funded NGOs, rich NGOs and the Hindu mass organisations. That's the combination that you see here and that's what makes you uneasy.

Arundhati Roy: yes, and when you look at the World Bank agenda, it's 600 anti-corruption plans and projects and what it says, what it believes, then it just becomes as clear as day what's going on here.

Sagarika Ghose: And what is going on, just to push you on that one?

Arundhati Roy: What I said, that you stop concentrating on the corruption of government officers when you know of governments, politicians, and leaving out the huge corporate world, the media, the NGOs who have taken over traditional government functions of electricity, water, mining, health, all of that. Why concentrate on this and not on that? I think that's a very, very big problem.

Sagarika Ghose: So it was a protest movement of the entitled and the protest movement of the privileged. Arundhati Roy thanks very much indeed for joining us.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)