Figures give fuel to claims that profiteering has played a big part in the UK’s high levels of inflation writes Phillip Inman in The Guardian

British companies have boosted their profitability, according to the latest official figures, insulating themselves against cost pressures and fuelling claims that profiteering has played a big part in the UK’s inflation story.

In a week when Joe Biden said he was only winning the war against inflation in the US because corporate profits were declining, figures released on Thursday by the Office for National Statistics showed UK business profits increased in the first quarter of 2023.

Manufacturing firms increased their net rate of return to 8.8% in the first quarter, from 8.4% in the fourth quarter of 2022. Services companies, which account for about three-quarters of economic activity, increased their net rate of return to 16.1%, an increase of 0.4 percentage points from the last three months of 2022.

The rate of return is a measure of profitability that shows the margin between operating profits and the cost of assets used to generate those profits. Unions have accused firms of putting up prices by more than the rise in their costs, a trend nicknamed greedflation.

It is a hot topic because the Bank of England has consistently said the small ups and downs registered by the ONS in its calculations of corporate profitability show little evidence of profiteering. It has repeatedly urged workers to restrain wage demands and played down the need to tell companies to restrain price rises.

On the other side of the argument stand a growing number of academics, thinktanks and unions.

The TUC general secretary, Paul Novak, said he was shocked by the ONS figures, which he claimed showed “a culture of entitlement is alive and well” among the large corporations that he said were mostly to blame for higher prices.

Sharon Graham, the head of the Unite union, arguably credited with doing more than anyone in the UK to promote research into corporate profits, said companies were exploiting a crisis.

Philip King, a former government adviser and small business commissioner until 2021, said many small and medium-sized companies would wonder what the fuss was about. He said it was clear from the figures that “companies are maintaining their profitability despite the difficult trading conditions they have faced”, and it was large businesses that would be to blame. These “typically have more flexibility when it comes to increasing prices and cutting costs”, he said.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and many leading academics say steady profit margins show businesses are doing better than any other participants in the economy, in particular workers.

An OECD report last month found average profit margins in the UK increased by almost a quarter between the end of 2019 and early 2023. Stefano Scarpetta, a director of the OECD, said it was “somewhat unusual that in a period of slowdown in economic activity we see profit picking up”.

George Dibb, an economist at the IPPR thinktank, said the Bank of England was “plain wrong” to consider steady profit margins a non-story.

On closer inspection the headline average is if anything worse than it first appears. Overall, the net rate of return for all non-financial businesses – a measure that excludes banks and insurance companies but includes North Sea oil and gas firms – increased from 9.8% in the last quarter of 2022 to 9.9% in the first quarter. That shows margins remained consistent through one of the worst winters for cost of living rises and cuts in disposable incomes for several generations.

However, excluding North Sea oil and gas firms, which showed a slump in profitability in the first quarter as energy prices fell from their peaks, dragging down the average, the level of profitability for most firms jumped from 9.6% in the last quarter of 2022 to 10.6% in the first quarter of 2023.

Richard Murphy, a professor of accounting at the University of Sheffield, said low wage rises in most sectors outside financial services meant large companies were probably doing much better than smaller ones.

Murphy said half of all UK company profits were generated by small and medium-sized companies and the other half by a few thousand larger firms.

Another interest rate rise is expected next month and the main reason given by the Bank will be that wages are rising too quickly, not that profits are rising too quickly. It is a stance that is going to become increasingly contentious.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label rise. Show all posts

Showing posts with label rise. Show all posts

Friday, 18 August 2023

A level Economics: UK's inflation is due to rise in corporate profit-taking

Thursday, 11 August 2022

We must tax profits now, freeze energy prices – and if necessary bring suppliers into the public sector

Without urgent action, families are seeing nothing more than pain now and pain later. There is a way through writes former PM and Chancellor Gordon Brown in The Guardian

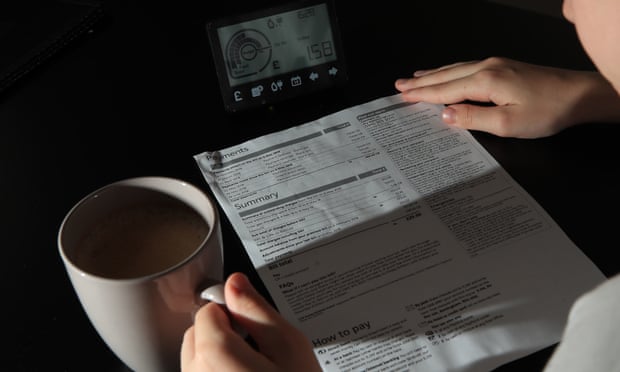

The energy cap has to be suspended before 26 August, the date on which an approximately 80% increase in our energy bills is expected to be announced. Photograph: Peter Byrne/PA

Time and tide wait for no one. Neither do crises. They don’t take holidays, and don’t politely hang fire – certainly not to suit the convenience of a departing PM and the whims of two potential successors and the Conservative party membership. But with the country already in the eye of a cost of living storm, decisions cannot be put on hold until a changeover on 5 September, leaving impoverished families twisting in the wind.

The energy cap has to be suspended before 26 August, the date on which an approximately 80% increase in our energy bills is expected to be announced. The Department for Work and Pensions computers, which adjust universal credit and legacy benefits, have to be reprogrammed in the next few days if help is to be given to all who need it when prices rise on 1 October. Voluntary cuts in energy usage – good for our green agenda – should, as has happened in Germany and France, be agreed upon now when the weather is good if we are to prevent rationing later when the weather turns bad. And windfall profits and bonuses have to be properly taxed now before the money flees the country.

There were two great lessons I learned right at the start of the last great economic crisis in 2008: never to be behind the curve but be ahead of events; and to get to the root of the problem. And it is not tax cuts or, as yet, a wage-price inflation spiral that are the most urgent priorities for action, but dealing with the soaring costs of fuel and food: the cause of half of our current inflation.

So it is indeed urgent that the candidates to be prime minister – and the current prime minister and chancellor – meet to make not just one or two but several urgently needed decisions: to suspend and fundamentally reform the energy price cap; to agree October payments for those who will not be able to afford to turn up their heating; to home in on alternative supplies abroad and open up appropriate storage facilities at home; to agree voluntary energy reductions; and to help pay for these measures with a watertight windfall tax on energy companies and a tax on the high levels of City bonus payments. For if we could remove the opportunity to avoid or opt out, as we did when imposing the windfall tax on privatised utilities in 1997 and the banker bonus levy of 2009, we could raise not just £5bn but as much as £15bn. This would be enough, for example, to give nearly 8 million low-income families just under £2,000 each.

All these measures should be based on a clear set of principles: that the right to a warm home is a human right; that we should do most for those who have least; and that no energy retailer should be allowed to additionally profit from the crisis.

Britain’s crises have one thing in common: a failure to invest

Larry Elliott

Read more

What’s more, British ministers – and no one has yet grasped this – should also be leading the way, as we did in 2009, in demanding coordinated international action with an emergency G20 early in September to address the fuel, food, inflation and debt emergencies. These are global problems that can only be fully addressed by globally coordinated solutions.

Tuesday’s forecast from Cornwall Insight of a £4,266 average annual energy price by January is remarkable. It means, as an immediate analysis carried out by Jonathan Bradshaw and Antonia Keung shows, that more than half of British households, 54%, will be in fuel poverty by October and two-thirds, 66%, by January. Six million households, an astonishing number, will be forced to pay an unprecedented 25% of their income in fuel costs and 4.4 million will be subject to a virtually unaffordable 30%.

So instead of allowing Ofgem to announce an increase on a scale that will send shock waves through every household, the government should pause any further increase in the cap; assess the actual costs of the energy supplies being sold to consumers by the major companies; and, after reviewing the profit margins, and examining how to make standing charges and social tariffs more progressive, negotiate separate company agreements to keep prices down. They should work with businesses to cut consumption, as is happening in France and Spain, which have imposed their own cap on energy prices, dictated more by what people can afford than the current wholesale gas price in the marketplace.

And if the companies cannot meet these new requirements, we should consider all the options we used with the banks in 2009: guaranteed loans, equity financing and, if this fails, as a last resort, operate their essential services from the public sector until the crisis is over.

With one of our main suppliers, Norway, seeking to retain its own gas for domestic use and France running into problems with its nuclear reactors, we are already running out of time to negotiate new deals with other international suppliers. And we are already missing out of additional capacity from Qatar, which has gone to mainland Europe. Over time, we can and must increase domestic production, and agree on a home insulation programme with the same urgency as our vaccination programme.

It’s true that Britain’s decade-long low growth, caused by low investment, has made us vulnerable to skill shortages and supply-side bottlenecks and thus higher inflation than our competitors. But most of the current rise in inflation has been generated from energy and food prices caused by the war in Ukraine and so removing the Bank of England’s independence is merely an exercise in blame shifting, as is direct criticism of the Treasury which, in my view, will take its lead from ministers.

It is the government that sets the inflation target and appoints the Bank’s main decision-makers. And it is the duty of government in a crisis to send the Bank an open letter telling it to set out a clear pathway over the coming years to return to stable prices. On the basis of an agreed inflation trajectory back to 2%, we should consider agreeing year-on-year wage settlements – starting with a flat rate of between £2-3,000 this year – so that hardworking families, especially those on the lowest incomes, can afford their energy bills without being plunged into poverty.

The truth is that without a plan the government is lurching from one crisis to another, failing to address the anxieties of families who see nothing more than pain now and pain later. But there is a way through from pain today to gain tomorrow, not just through the immediate relief I propose but in a clear strategy to move us from the 1.4% annual growth that the Conservatives have achieved back to a 2.5% trend growth rate. This is the one way to permanently end the cost of living crisis that British families have had to endure through an austerity decade.

No one can be secure when millions feel insecure and no one can be content when there is so much discontent. Churchill once said that those who build the present in the image of the past will utterly fail to meet the challenges of the future. Only bold and decisive action starting this week will rescue people from hardship and reunite our fractured country.

Time and tide wait for no one. Neither do crises. They don’t take holidays, and don’t politely hang fire – certainly not to suit the convenience of a departing PM and the whims of two potential successors and the Conservative party membership. But with the country already in the eye of a cost of living storm, decisions cannot be put on hold until a changeover on 5 September, leaving impoverished families twisting in the wind.

The energy cap has to be suspended before 26 August, the date on which an approximately 80% increase in our energy bills is expected to be announced. The Department for Work and Pensions computers, which adjust universal credit and legacy benefits, have to be reprogrammed in the next few days if help is to be given to all who need it when prices rise on 1 October. Voluntary cuts in energy usage – good for our green agenda – should, as has happened in Germany and France, be agreed upon now when the weather is good if we are to prevent rationing later when the weather turns bad. And windfall profits and bonuses have to be properly taxed now before the money flees the country.

There were two great lessons I learned right at the start of the last great economic crisis in 2008: never to be behind the curve but be ahead of events; and to get to the root of the problem. And it is not tax cuts or, as yet, a wage-price inflation spiral that are the most urgent priorities for action, but dealing with the soaring costs of fuel and food: the cause of half of our current inflation.

So it is indeed urgent that the candidates to be prime minister – and the current prime minister and chancellor – meet to make not just one or two but several urgently needed decisions: to suspend and fundamentally reform the energy price cap; to agree October payments for those who will not be able to afford to turn up their heating; to home in on alternative supplies abroad and open up appropriate storage facilities at home; to agree voluntary energy reductions; and to help pay for these measures with a watertight windfall tax on energy companies and a tax on the high levels of City bonus payments. For if we could remove the opportunity to avoid or opt out, as we did when imposing the windfall tax on privatised utilities in 1997 and the banker bonus levy of 2009, we could raise not just £5bn but as much as £15bn. This would be enough, for example, to give nearly 8 million low-income families just under £2,000 each.

All these measures should be based on a clear set of principles: that the right to a warm home is a human right; that we should do most for those who have least; and that no energy retailer should be allowed to additionally profit from the crisis.

Britain’s crises have one thing in common: a failure to invest

Larry Elliott

Read more

What’s more, British ministers – and no one has yet grasped this – should also be leading the way, as we did in 2009, in demanding coordinated international action with an emergency G20 early in September to address the fuel, food, inflation and debt emergencies. These are global problems that can only be fully addressed by globally coordinated solutions.

Tuesday’s forecast from Cornwall Insight of a £4,266 average annual energy price by January is remarkable. It means, as an immediate analysis carried out by Jonathan Bradshaw and Antonia Keung shows, that more than half of British households, 54%, will be in fuel poverty by October and two-thirds, 66%, by January. Six million households, an astonishing number, will be forced to pay an unprecedented 25% of their income in fuel costs and 4.4 million will be subject to a virtually unaffordable 30%.

So instead of allowing Ofgem to announce an increase on a scale that will send shock waves through every household, the government should pause any further increase in the cap; assess the actual costs of the energy supplies being sold to consumers by the major companies; and, after reviewing the profit margins, and examining how to make standing charges and social tariffs more progressive, negotiate separate company agreements to keep prices down. They should work with businesses to cut consumption, as is happening in France and Spain, which have imposed their own cap on energy prices, dictated more by what people can afford than the current wholesale gas price in the marketplace.

And if the companies cannot meet these new requirements, we should consider all the options we used with the banks in 2009: guaranteed loans, equity financing and, if this fails, as a last resort, operate their essential services from the public sector until the crisis is over.

With one of our main suppliers, Norway, seeking to retain its own gas for domestic use and France running into problems with its nuclear reactors, we are already running out of time to negotiate new deals with other international suppliers. And we are already missing out of additional capacity from Qatar, which has gone to mainland Europe. Over time, we can and must increase domestic production, and agree on a home insulation programme with the same urgency as our vaccination programme.

It’s true that Britain’s decade-long low growth, caused by low investment, has made us vulnerable to skill shortages and supply-side bottlenecks and thus higher inflation than our competitors. But most of the current rise in inflation has been generated from energy and food prices caused by the war in Ukraine and so removing the Bank of England’s independence is merely an exercise in blame shifting, as is direct criticism of the Treasury which, in my view, will take its lead from ministers.

It is the government that sets the inflation target and appoints the Bank’s main decision-makers. And it is the duty of government in a crisis to send the Bank an open letter telling it to set out a clear pathway over the coming years to return to stable prices. On the basis of an agreed inflation trajectory back to 2%, we should consider agreeing year-on-year wage settlements – starting with a flat rate of between £2-3,000 this year – so that hardworking families, especially those on the lowest incomes, can afford their energy bills without being plunged into poverty.

The truth is that without a plan the government is lurching from one crisis to another, failing to address the anxieties of families who see nothing more than pain now and pain later. But there is a way through from pain today to gain tomorrow, not just through the immediate relief I propose but in a clear strategy to move us from the 1.4% annual growth that the Conservatives have achieved back to a 2.5% trend growth rate. This is the one way to permanently end the cost of living crisis that British families have had to endure through an austerity decade.

No one can be secure when millions feel insecure and no one can be content when there is so much discontent. Churchill once said that those who build the present in the image of the past will utterly fail to meet the challenges of the future. Only bold and decisive action starting this week will rescue people from hardship and reunite our fractured country.

Friday, 1 July 2022

Striking workers are providing the opposition that Britain desperately needs

Andy Beckett in The Guardian

In Britain, more than in most democratic countries, going on strike is a risk. Your employer, the government, most of the media, much of the public and often the opposition parties are likely to be against you – or, at best, unsupportive. Your loss of income is unlikely to be made up by strike pay. Your behaviour on the picket line will be subject to what Tony Blair described approvingly in 1997 as “the most restrictive” trade union laws “in the western world”.

In very public ways, you will be breaking the rules of the modern economy: refusing to work, inconveniencing consumers, acting collectively rather than individually, and making demands for more money openly – rather than in private, as more powerful people do. If you are on the left, you are likely to be told again and again that your strike is politically counterproductive.

Such are the written and unwritten laws that have constricted British strikes for approaching half a century, ever since the walkouts of the 1978-79 winter of discontent inadvertently did so much to bring Margaret Thatcher to power and to provoke the counter-revolution against workers that still continues today. Many voters have long got used to the idea that strikes are a minority pursuit associated with a bygone age to which the country must not return. Boris Johnson’s government, with its especially strong intolerance of dissent, aims to demonise and marginalise strikes even further.

Yet this summer, more and more Britons are striking or considering striking regardless. From railway workers to barristers, firefighters to doctors, Post Office workers to teachers, nurses to civil servants, council workers to British Telecom engineers, an unusually large potential strike wave is building. Its social breadth, the range of occupations affected and the atmosphere on some picket lines all suggest that something politically significant may be happening.

At the first barristers’ protest, outside the Old Bailey in London this week, an already excited crowd of advocates in courtroom wigs and gowns burst into prolonged applause when they were joined by a few activists in shorts and jeans from the RMT. It’s not every day that you see such camaraderie between self-employed professionals who rely heavily on trains and striking transport workers carrying a banner that calls for “the supersession of the capitalist system by a socialistic order of society”.

The cost of living crisis, and the refusal of the government and other employers to raise wages accordingly, is the immediate reason for this summer’s “wave of resistance”, as Mick Lynch of the RMT union calls it. Yet the causes go deeper: more than a decade of stagnant or falling wages; the long Conservative squeeze on the public sector; and the whole transformation of the British economy since the 1970s, which has effectively taken money from workers and given it to employers, shareholders and the wealthy.

![]()

Public dissatisfaction with this model has been growing for years. In the latest British Social Attitudes survey, 64% agree that “‘ordinary people do not get their fair share of the nation’s wealth” – up from 57% in 2019, and far greater than the support for any party. As Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn tapped into this discontent. But the end of his tenure, and Keir Starmer’s apparent lack of interest in its redistributive ideas, has created a vacuum where a movement with a radical economic agenda ought to be.

It’s possible that the strike wave could become one such movement. While support for the strikes has been stronger than expected - the pollster Savanta ComRes found that even 38% of Tory voters considered the highly disruptive rail strikes “justified”; among younger people this attitude was particularly prevalent. In the same survey, 72% of under-35s backed the strikers. Since few of them have ever been on strike themselves – less than a quarter of trade unionists are under 35 – then the likely explanation is not shared experience but shared disenchantment. Young people, like many of the strikers, have been particularly badly served by the status quo.

Many young people supported Corbyn for the same reason. And there are other similarities between the two movements. Former Corbyn advisers such as James Schneider, Corbyn himself, and the parliamentary Labour left all support the strikers. Green activists, once an important part of Corbyn’s coalition, have joined RMT picket lines. Like Labour’s 2017 election manifesto, Lynch uses clear, populist language – “every worker in Britain” should get a much better pay deal, he told Question Time – and its effectiveness has taken the media by surprise. Support for the RMT strike rose after his TV appearances.

Could the strikers succeed, not just in getting fairer pay deals but in beginning to change how the economy works? It’s an immense task, which Labour under Corbyn sometimes talked about compellingly but never came close to carrying out. And as the strikes widen and lengthen, public opinion may turn against them. Walking to work because of a train strike will seem less of a novelty and more of an imposition if that dispute drags on into the autumn. One of the obvious but often forgotten lessons of the winter of discontent is that voters often hate strikes in cold weather.

Excited union talk about building new mass movements has proved over-optimistic in the past, for example during David Cameron’s government. The proportion of British employees who are union members has stabilised in recent years, after decades of decline, but by historic standards it is still low: less than one in four. And the fact that Starmer is not prepared to support the strikers removes one of the main means by which their campaigns could be amplified.

Yet for almost a decade now, British politics has not followed the expected paths. It may be that an economy built on poor wages was politically and socially sustainable only while inflation stayed low. That relatively stable and docile era may be over. Recently, the leftwing website Left Foot Forward listed some of the pay rises already won this summer by the increasingly assertive trade union Unite: “300 workers at Gatwick get 21 per cent”, “300 HGV drivers win 20 per cent”. In post-Thatcher Britain, such transfers of wealth to the workers – not just matching but far exceeding the rate of inflation – aren’t supposed to happen. But they are.

Unlike in the 1980s, when the iron lady beat Britain’s last big wave of strikes, unemployment is low and the supply of labour is short. If strikers don’t like a pay offer, sometimes they can threaten to go and work for someone who pays more. You could call it an example of something the Tories talk less about these days: market forces.

In Britain, more than in most democratic countries, going on strike is a risk. Your employer, the government, most of the media, much of the public and often the opposition parties are likely to be against you – or, at best, unsupportive. Your loss of income is unlikely to be made up by strike pay. Your behaviour on the picket line will be subject to what Tony Blair described approvingly in 1997 as “the most restrictive” trade union laws “in the western world”.

In very public ways, you will be breaking the rules of the modern economy: refusing to work, inconveniencing consumers, acting collectively rather than individually, and making demands for more money openly – rather than in private, as more powerful people do. If you are on the left, you are likely to be told again and again that your strike is politically counterproductive.

Such are the written and unwritten laws that have constricted British strikes for approaching half a century, ever since the walkouts of the 1978-79 winter of discontent inadvertently did so much to bring Margaret Thatcher to power and to provoke the counter-revolution against workers that still continues today. Many voters have long got used to the idea that strikes are a minority pursuit associated with a bygone age to which the country must not return. Boris Johnson’s government, with its especially strong intolerance of dissent, aims to demonise and marginalise strikes even further.

Yet this summer, more and more Britons are striking or considering striking regardless. From railway workers to barristers, firefighters to doctors, Post Office workers to teachers, nurses to civil servants, council workers to British Telecom engineers, an unusually large potential strike wave is building. Its social breadth, the range of occupations affected and the atmosphere on some picket lines all suggest that something politically significant may be happening.

At the first barristers’ protest, outside the Old Bailey in London this week, an already excited crowd of advocates in courtroom wigs and gowns burst into prolonged applause when they were joined by a few activists in shorts and jeans from the RMT. It’s not every day that you see such camaraderie between self-employed professionals who rely heavily on trains and striking transport workers carrying a banner that calls for “the supersession of the capitalist system by a socialistic order of society”.

The cost of living crisis, and the refusal of the government and other employers to raise wages accordingly, is the immediate reason for this summer’s “wave of resistance”, as Mick Lynch of the RMT union calls it. Yet the causes go deeper: more than a decade of stagnant or falling wages; the long Conservative squeeze on the public sector; and the whole transformation of the British economy since the 1970s, which has effectively taken money from workers and given it to employers, shareholders and the wealthy.

Public dissatisfaction with this model has been growing for years. In the latest British Social Attitudes survey, 64% agree that “‘ordinary people do not get their fair share of the nation’s wealth” – up from 57% in 2019, and far greater than the support for any party. As Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn tapped into this discontent. But the end of his tenure, and Keir Starmer’s apparent lack of interest in its redistributive ideas, has created a vacuum where a movement with a radical economic agenda ought to be.

It’s possible that the strike wave could become one such movement. While support for the strikes has been stronger than expected - the pollster Savanta ComRes found that even 38% of Tory voters considered the highly disruptive rail strikes “justified”; among younger people this attitude was particularly prevalent. In the same survey, 72% of under-35s backed the strikers. Since few of them have ever been on strike themselves – less than a quarter of trade unionists are under 35 – then the likely explanation is not shared experience but shared disenchantment. Young people, like many of the strikers, have been particularly badly served by the status quo.

Many young people supported Corbyn for the same reason. And there are other similarities between the two movements. Former Corbyn advisers such as James Schneider, Corbyn himself, and the parliamentary Labour left all support the strikers. Green activists, once an important part of Corbyn’s coalition, have joined RMT picket lines. Like Labour’s 2017 election manifesto, Lynch uses clear, populist language – “every worker in Britain” should get a much better pay deal, he told Question Time – and its effectiveness has taken the media by surprise. Support for the RMT strike rose after his TV appearances.

Could the strikers succeed, not just in getting fairer pay deals but in beginning to change how the economy works? It’s an immense task, which Labour under Corbyn sometimes talked about compellingly but never came close to carrying out. And as the strikes widen and lengthen, public opinion may turn against them. Walking to work because of a train strike will seem less of a novelty and more of an imposition if that dispute drags on into the autumn. One of the obvious but often forgotten lessons of the winter of discontent is that voters often hate strikes in cold weather.

Excited union talk about building new mass movements has proved over-optimistic in the past, for example during David Cameron’s government. The proportion of British employees who are union members has stabilised in recent years, after decades of decline, but by historic standards it is still low: less than one in four. And the fact that Starmer is not prepared to support the strikers removes one of the main means by which their campaigns could be amplified.

Yet for almost a decade now, British politics has not followed the expected paths. It may be that an economy built on poor wages was politically and socially sustainable only while inflation stayed low. That relatively stable and docile era may be over. Recently, the leftwing website Left Foot Forward listed some of the pay rises already won this summer by the increasingly assertive trade union Unite: “300 workers at Gatwick get 21 per cent”, “300 HGV drivers win 20 per cent”. In post-Thatcher Britain, such transfers of wealth to the workers – not just matching but far exceeding the rate of inflation – aren’t supposed to happen. But they are.

Unlike in the 1980s, when the iron lady beat Britain’s last big wave of strikes, unemployment is low and the supply of labour is short. If strikers don’t like a pay offer, sometimes they can threaten to go and work for someone who pays more. You could call it an example of something the Tories talk less about these days: market forces.

Thursday, 20 May 2021

How Sadhguru built his Isha empire. Illegally

Anish Daolagupu

Jaggi Vasudev, Anglophone India’s star godman, has challenged on more occasions than one that if the accusations of illegal deeds that have followed him around like ardent devotees were ever proved, he would quit India. The charges are legion, contained in testimonies of the allegedly wronged and tomes of government records. And there is much there, as Newslaundry found after examining a whole lot of them, to, at the very least, merit an investigation. Absent that, the accusations remain just that, accusations, merely a nuisance in his way as Vasudev goes about expanding his vast religio-cultural and business empire, the Isha Foundation. And, in the process, building himself up as arguably the country’s most influential godman.

But what precisely are the accusations against Vasudev, or Sadhguru as his devotees know him? Have they ever been investigated? If yes, what was the outcome? If no, why not? Did he use his godman persona and influence to indulge in illegalities or did the alleged illegalities enable his rise to fame and fortune?

To answer such questions, Newslaundry spoke with public servants, activists, and whistleblowers; trawled government records on the foundation; and examined court cases filed against them over the years and investigations conducted.

What we pieced together is really just the same old story of greed, corruption, and abuse of socio-religio-cultural sentiment for material enrichment. At the centre of this story is an Adivasi hamlet called Ikkarai Boluvampatti in Tamil Nadu’s Coimbatore.

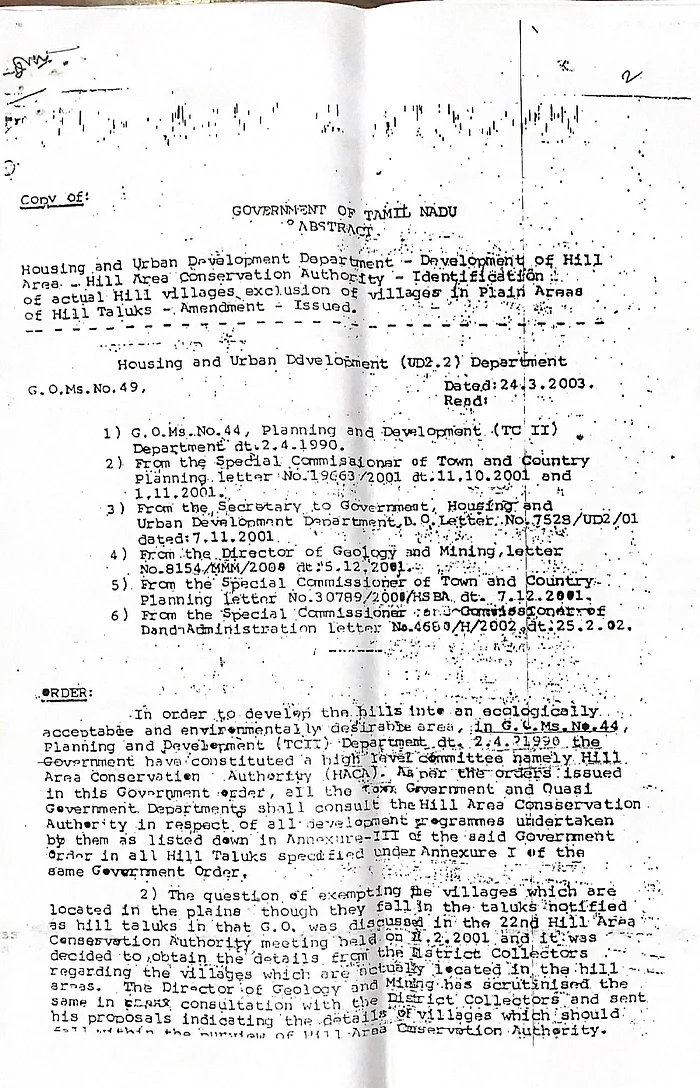

Ikkarai Boluvampatti, in the foothills of the Velliangiri hills, is where the Isha Foundation is headquartered on a sprawling 150-acre campus of 77 large and small structures, including the Isha ashram, built between 1994 and 2011 in blatant violation of laws and rules. The campus is adjacent to the Bolampatty Reserve Forest, an elephant habitat in the Nilgiris biosphere reserve, and along the Thanikandi-Marudhamalai migration corridor of the pachyderms. So, human activity, let alone construction, is regulated by the Hill Area Conservation Authority, or HACA, set up in 1990 to preserve wildlife and ecology of forested hill regions of Tamil Nadu.

Here, construction on over 300 sq metres of land can’t be done without HACA’s approval. Yet, records obtained by Newslaundry from the state departments of forest, town and country planning, and housing and urban development show that from 1994 to 2011, Isha constructed on 63,380 sq meters and created an artificial lake on another 1,406.62 sq metres at Ikkarai Boluvampatti, without approval. Vasudev and his foundation have said they got permission to build on about 32,855 sq metres from the local panchayat, but the rural body doesn’t have the power to authorise construction in areas under HACA.

Isha did apply for approval from HACA in 2011, but after they had already built several structures. In July 2011, a forest department document shows, Isha asked HACA to greenlight illegal constructions on 63,380 sq meters as well as new constructions on 28582.52 sq metres. Taking up the application, V Thirunavukkarasu, then Coimbatore’s forest officer, visited the Isha ashram in February 2012. He found Isha had illegally constructed a series of buildings, including on the 28,582.52 sq meter plot for which it had gone to HACA for approval.

Thirunavukkarasu also found that the compound wall of the ashram and front gate were built from the forest land. Moreover, Isha’s many constructions and the resultant rush of visitors to the ashram had obstructed the elephant corridor, heightening man-animal conflict. So, he denied them approval. In October that year, Isha withdrew its application on the prexet of amending it. They didn’t file it again until 2014.

Thirunavukkarasu would return to Coimbatore as the chief conservator of forests in 2018, only to be moved out after just four days.

MS Parthipan, a forest ranger, too visited the Isha ashram in 2012. He found some of its lands fell on routes elephants used to move between Sadivayal and Thanikkandi. Since Isha had illegally erected buildings, walls and electric fences on these lands, elephants were forced to emerge from the forest between Semmedu and Narseepuram, trampling crops and attacking villagers.

“Any construction requiring over 300 sq meters of land requires HACA’s permission. Isha undertook construction without permission over a large area. They built structures first and then applied for approval. Whenever they did seek permission for new construction, they didn’t wait for our nod and simply started building,” a forest official who was privy to Parthipan’s inspection said on the condition of anonymity. “Isha’s lands were inside the elephant corridor and they were obstructing it, so they didn’t get clearance.”

Isha has marked at least 33 structures at the Ikkarai Boluvampatti campus for religious use which means they are considered public buildings under Tamil Nadu’s planning rules. Such structures require approvals from the district collector and the deputy director for town and country planning to build. Isha, records from the housing and urban development department show, didn’t bother taking these approvals.

Instead, they went to the panchayat, which isn’t empowered to grant such permissions without consulting the town and country planning department. The foundation did eventually go to the planning department for approval in 2011, but only after they had erected a series of structures – illegally. Aside from seeking approval for what they had built over the previous 15 years, the foundation asked the planning department for permission to construct 27 new buildings. The application, however, was incomplete and the department told them to file a new one by February 2012.

Isha breached the deadline and only sent a new application seven months later. Subsequently, when planning officials visited the ashram in October 2012 they found construction of the new buildings had already begun. They ordered the foundation to immediately stop all construction and followed up with a notice in November 2012. Isha didn’t care.

Finally, in December 2012, the planning department sent another notice directing Isha to demolish all illegal structures within a month. The foundation challenged the notice before the town and country planning commissioner. The matter is still hanging fire.

At the time, K Mookiah was deputy director, the town and country planning department, Coimbatore. Why did his department not act against Isha when they disregarded its orders? “After a month of issuing the notice I was transferred out,” he replied. “I don’t know what happened after that. I don’t know whether they have taken the approval or not.”

By 2012, Isha had constructed as many as 50 structures and was building 27 more, all illegally.

The foundation’s illegalities didn’t go unchallenged.

For the past eight years, M Vetri Selvan of the NGO Poovulagin Nanbargal has been fighting against Vasudev’s illegal constructions in the Madras high court, where he filed four petitions in 2013 and 2014. In his pleas, Selvan asked that the planning department’s order for demolition of Isha’s illegal structures be carried out, officials who had not acted against its illegalities be punished, Isha Sanskriti School’s illegal operation be stopped, and provision of cheap electricity to the Isha campus be stopped.

The pleas saw a total of 10 hearings from March 2013 to April 2014. And none since. “Our first petition regarding the demolition of Isha’s illegal construction was heard on March 8, 2013. A notice was issued to Isha, district collector, forest department, HACA, village panchayat. At the next hearing on March 25, 2013, Isha’s advocate sought time to file a counter.

On June 20, Isha, the planning department and the state government all filed their responses and the matter was adjourned. On August 22, 2013, we filed three more petitions and a combined hearing on all four pleas took place the next day. Both sides made arguments, but there was no reply from the state government and the matter was adjourned again,” he said. “At a hearing on March 13, 2014, the state school authority submitted that they hadn’t given Isha permission to run a school. After that, the court said the final hearing would happen once all the respondents had filed their counters. There has been no hearing since.”

In 2017, Selvan filed a petition against Isha’s Mahashivratri celebration, but the court didn’t entertain it because his previous pleas were still pending.

“The court also said I’d filed the petition with ulterior motive,” he added. “Man-animal conflict in and around the forests of Coimbatore has seen a spurt in the past 15-20 years. Primary reason is illegal construction in the elephant habitat, and Isha is involved on a wide scale. We are trying to save the natural environment of this area, to preserve its biodiversity. That’s why we are fighting against Isha’s illegal constructions. It’s not a personal feud.”

Isha's Adiyogi statue.

After he was turned away by the high court, Selvan went to the National Green Tribunal against Isha’s “destruction of environment and wildlife”. Three years later, the NGT directed Isha and the local administration to ensure big functions at the ashram such as the Mahashivratri celebration didn’t cause pollution.

Selvan wasn’t alone knocking the high court’s doors with a complaint against Isha in 2017. The Velliangiri Hill Tribal Protection Society also filed a plea, through P Muthammal, 49, an Adivasi from the Muttathu Ayal settlement in Ikkarai Boluvampatti.

Muthammal pleaded that rising man-animal conflict, for which Isha’s illegal constructions were mainly to blame, had made the lives of Adivasis difficult. He also objected to the foundation’s 112-foot Adiyogi statue, noting that it had been built without necessary clearances.

Replying to the petition, R Selvaraj, then deputy director, town and country planning, confirmed that the statue had been built without his department’s approval.

But by the time Selvaraj filed the reply, on February 28, 2017, the statue had already been inaugurated by none less than the prime minister.

That Modi didn’t hesitate to inaugurate the statue even though it was mired in a legal challenge was telling. A key reason Isha has got away with blatantly violating rules is that it has been enabled by political authorities, particularly the Tamil Nadu government.

Most blatantly, the forest department has dramatically changed its view that the Isha ashram is situated in the elephant corridor.

In 2012, records seen by Newslaundry show, Coimbatore’s forest officer told the state’s principal chief conservator of forests that Isha had built on land in the elephant corridor and its constructions and the rush of the devotees to the ashram – nearly two lakh on on Mahashivratri alone – had heightened man-animal conflict. Installation of powerful lights and high-decibel audio, not least for the Mahashivratri celebration, had only worsened the situation.

Similarly, a 2013 notification issued by the district collector stated in no uncertain terms, though without naming Isha, that illegal construction near the reserve forest in Ikkarai Boluvampatti was increasingly obstructing the corridor for elephants, causing the animals to damage life and property. The notice threatened to cut power, water ,sealing and demolition of the premises which had been built without HACA’s approval.

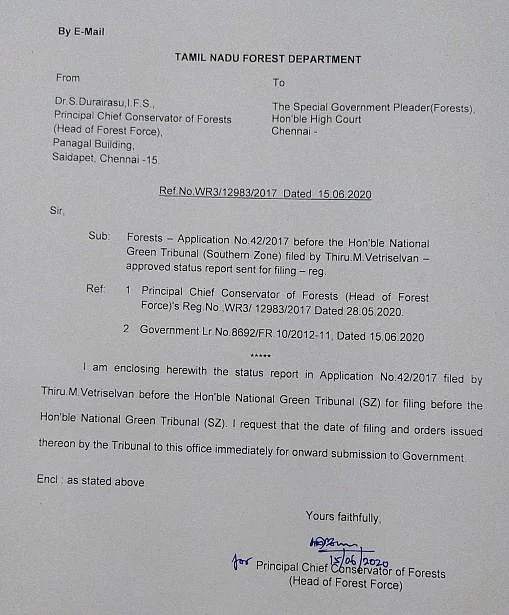

By 2020, however, the forest authorities were singing a discordant tune. In a June 2020 status report submitted to the National Green Tribunal, principal chief conservator of forests P Durairasu, claimed that the Isha campus was “adjacent” to the Ikkarai Boluvampatti Block 2 reserve forest, which was a “famous elephant habitat” but not a designated elephant corridor. For their yearly migration, he added, elephants passed near where the Isha ashram was situated in Ikkarai Boluvampatti but this spot wasn’t an authorised elephant corridor.

The swing in the forest department’s position on Ikkarai Boluvampatti would prove conveniently beneficial for Isha. In March last year, the EK Palaniswami government directed the regularisation of plots which have been built on without approval in the hill areas, including HACA lands that supposedly do not fall within the elephant corridor. They include Ikkarai Boluvampatti.

“We believe this rule has been brought to indirectly help the Isha Foundation regularise its illegal constructions,” claimed G Sundarrajan, an activist with the environmental advocacy group Poovulagin Nanbargal. “The government hasn’t yet notified they have made this rule.”

In 2017, after Isha had applied for HACA approval for constructions that they had already erected, H Basavraju, then the principal chief conservator, set up a committee to examine the submission. The committee found that Isha’s constructions were damaging to local wildlife and environment, and asked the district forest officer to recommend post-construction approval only if Isha made changes to the buildings, stopped using a few roads and agreed to not make any new construction within 100 metres of the forest reserve.

The same year, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India pulled up the state’s forest department for not stopping Isha’s illegal constructions despite knowing about them since 2012. The constructions had been done without required approvals from HACA, the CAG reiterated.

Responding to the CAG’s report, Isha claimed they have received HACA approval for all their constructions on March 16, 2017. But the committee formed by the principal chief conservator to inspect the Isha campus and decide on its application was formed only on March 17, and submitted its report on March 29. In fact, it wasn’t until April 4 that the principal chief conservator made a conditional recommendation to the town and country planning to grant post-construction approval to Isha. The planning department, in turn, directed its regional deputy director in Coimbatore on May 3 to issue post-construction to Isha provided they paid the required fees and adhered to the conditions of the forest department. How then is it possible for the HACA to have approved Isha’s constructions on March 16?

Isha refused to respond to this and other specific allegations. Replying to an email by Newslaundry seeking comment, a spokesperson for the foundation warned, “While your assumptions and presumptions are not material to us, should you slander the foundation, you will do so at your own risk.”

Tamil Nadu doesn’t have a mechanism to give post-construction clearance. The town and country planning department can regularise a construction post facto but only if its conditions are met. It can’t give an environmental clearance, however.

Basavraju, principal chief conservator at the time, wouldn’t answer our questions about recommending post-construction approval for Isha’s structures. His successor, Durairasu, who filed the status report to the National Green Tribunal, said, “Conditions were levied and then only recommendations were made. I don’t know whether they followed the conditions. As per my knowledge they have not received permission from HACA until now.”

Rajamani, who as Coimbatore’s district collector heads HACA, said he didn’t want to talk about the agency’s approval to Isha. “You can write whatever you want,” he added.

Saturday, 5 September 2020

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)