Or why it may not be a bad idea to reverse your bat grip

SB TANG in Cricinfo

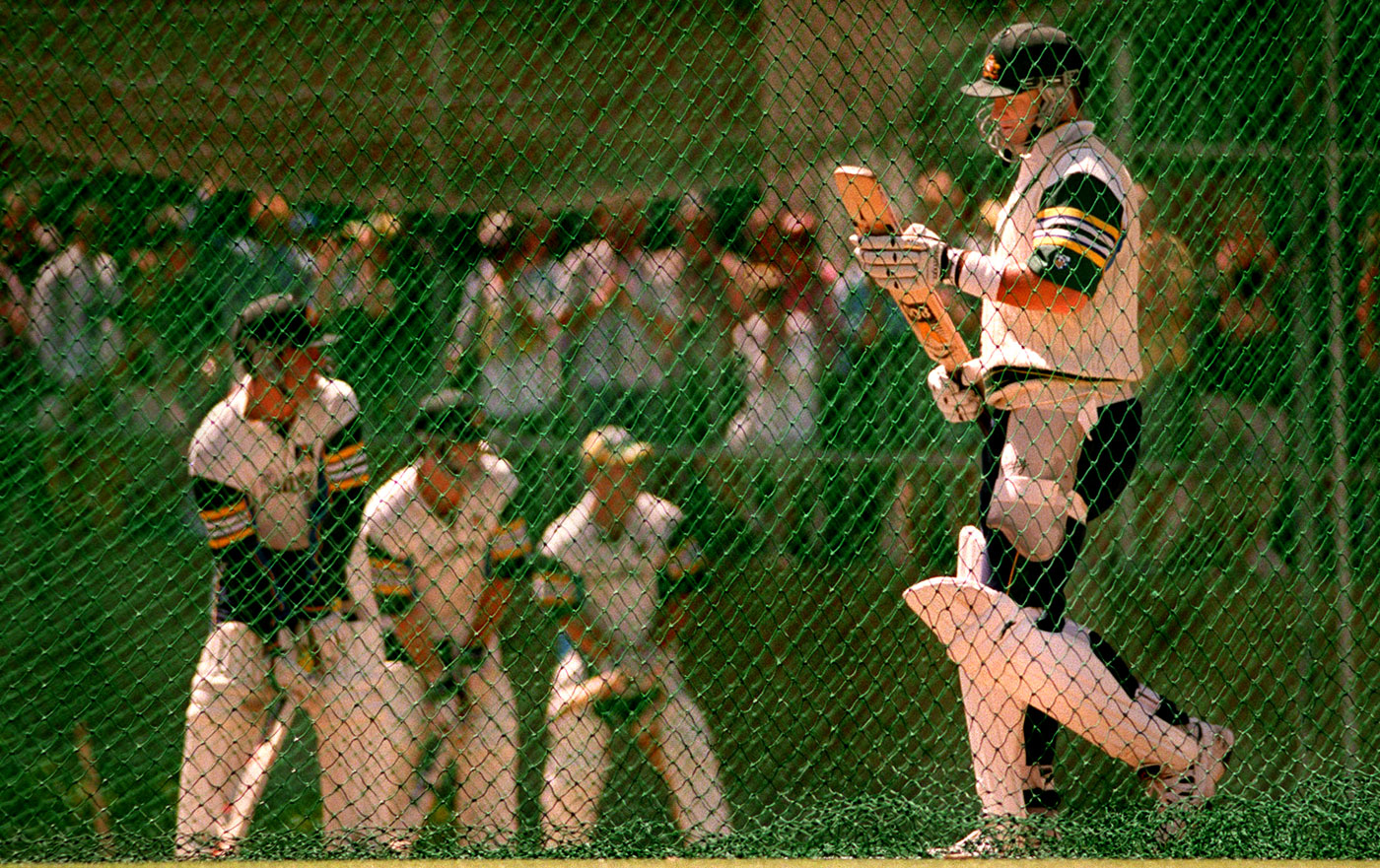

One summer's day, some 34 years ago, seven-year-oldMike Hussey was at home in the beachside Perth suburb of Mullaloo doing what he always did on a morning in the last week of December: watching the Boxing Day Test on TV. After seeing his hero Allan Border take Australia to the brink of a famous victory, only to fall an agonising three runs short, Hussey went out into his backyard and did something that few Australian cricketers have done before or since: he changed hands, permanently.

Hussey is naturally right-handed. He writes right-handed, plays tennis right-handed, brushes his teeth right-handed, picks up a spoon right-handed, and throws and bowls with his right arm. When he first picked up a cricket bat, he picked it up right-handed. But on that fateful sunny morning he decided to try batting left-handed, like Border, and ended up sticking with it for the rest of his life.

In so doing, Hussey may well have inadvertently bequeathed himself a natural technical advantage, for if there is one thing that the two main schools of batsmanship that exist in Australia - the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) school and the native autodidactic school headed by Sir Donald Bradman and Greg Chappell - agree on, it is this: a grip with a firm top hand and loose bottom hand is optimal for good batsmanship.

Logically it is easier for a batsman who holds the bat with his naturally stronger hand as the top hand (and his naturally weaker hand as the bottom hand) to grip it with a firm top hand and a loose bottom hand. When Hussey switched to batting left-handed, his naturally stronger right hand became his top hand. That wasn't what motivated his change - he did it "purely" because he "wanted to be like Allan Border" - and even when he became a world-class batsman, Hussey was generally not conscious of "the dominance of one hand over another", except when batting at the death of a one-day or T20 game. It was then, he told the Cricket Monthly, that he took the firm top-hand, loose bottom-hand grip to its logical apotheosis:

"At the end of a one-day game or a T20 game, when you're looking to basically hit sixes every ball… I made a conscious effort to really loosen the grip of my bottom hand. So I'd basically just rest the bottom hand [on the bat] on one finger - my index finger - because I was finding that when I was looking to slog, even though my bottom left hand was my less [naturally] dominant hand, it was gripping the bat too hard and taking control of the bat too quickly and affecting my swing. I wasn't hitting through the line of the ball as well as I would have liked."

Greg Chappell, Cricket Australia's first full-time national talent manager, has a clear vision for how Australia can continue to nurture its distinctive style of cricket - aggressive, attacking and winning. A firm-top-hand-loose-bottom-hand grip - a trait that Bradman himself believed to be "of supreme importance when playing a forward defensive shot" - is part of that vision. "It is", says Chappell in a recent interview with the Cricket Monthly, "essential for good batsmanship".

Firstly, he explains, such a grip enables a batsman to obtain the optimal bat swing - a pendular motion that maximises his chances of hitting the ball in the middle of the sweet spot. A batsman with that grip "initiates" the movement of his bat with his top hand and relegates his bottom hand to "a secondary role in the initiation [process]" as "the fulcrum". This naturally encourages him to pick up his bat so that, in his backswing, it is pointing between first slip and gully. His bat will then naturally and automatically drop back down onto the line of the ball when he is executing a straight-bat shot. The bat will "be on line [with the ball] from the top of the backswing all the way through the intended shot".

Secondly, a firm-top-hand-loose bottom-hand grip helps a batsman to stay balanced, with his weight on the balls of his feet like a champion boxer ready to throw (or ride) a punch, able to "move forward or back" into the optimal position to play the ball and synchronise the movements of his entire body.

The MCC agrees with Chappell insofar as both its instructional books constantly emphasise the importance of playing with a strong top hand, a high front elbow and a loose bottom hand, especially when executing forward defensives and front-foot drives. The problem is that the MCC's two specific written injunctions regarding how to pick up and grip a bat make it inherently difficult for batsmen to use a strong-top-hand-loose-bottom-hand grip. The MCC instructs batsmen to pick up the bat so that "the back [knuckle-side] of [their top] left hand, if the bat is held upright, is fac[ing] somewhere between mid-off and extra cover" and the hands form, with the thumb and first finger of each, two aligned Vs whose central line runs "half-way between the outer edge of the bat and the splice".

Pick up a bat with that MCC-prescribed grip and attempt to play a straight drive, off drive or cover drive. You will find that that grip encourages you to push through the shot with a firm bottom hand that shuts your bat face towards the on side. That is certainly what a young Chappell - saddled with the MCC grip taught to him at the age of five by a local youth coach with a very English pedagogy - found. Even after making his Sheffield Shield debut at the age of 18, he scored "about three-quarters" of his runs through the on side, a limitation so acute that it was the subject of much sledging from his opponents (and team-mates). Chappell recalls, in his 2011 autobiography Fierce Focus, that his own captain at South Australia, Les Favell, said to him, "I hope you won't lose sight of the fact that there are two sides of the wicket".

The firm bottom-hand tendency created by this grip is exacerbated by the explicit written instructions issued by the MCC to kids in Cricket - How to Play: pick up a bat as if you are "gripping an axe" with two hands to chop some wood that is lying on the ground. This instruction would - according to sports scientists David Mann, Oliver Runswick and Peter Allen - typically encourage kids to pick up a bat with their dominant hand as the bottom hand on the handle. Logically, this would make them more likely to play with a strong bottom hand.

In England, the influence of the MCC's coaching scriptures has always been strong. This can be seen in the faithful reproduction of the MCC's two injunctions regarding a batsman's grip in coaching manuals authored by the likes of Geoff Boycott and Robin Smith. In Australia, the influence has generally been much weaker. Seven of Australia's top 15 Test run scorers - Neil Harvey, Matthew Hayden, Michael Clarke, Justin Langer, Mark Taylor, Mike Hussey and Adam Gilchrist - have gripped a cricket bat with their naturally dominant hand as their top hand, suggesting either a blissful ignorance or a deliberate contravention of the MCC's two injunctions.

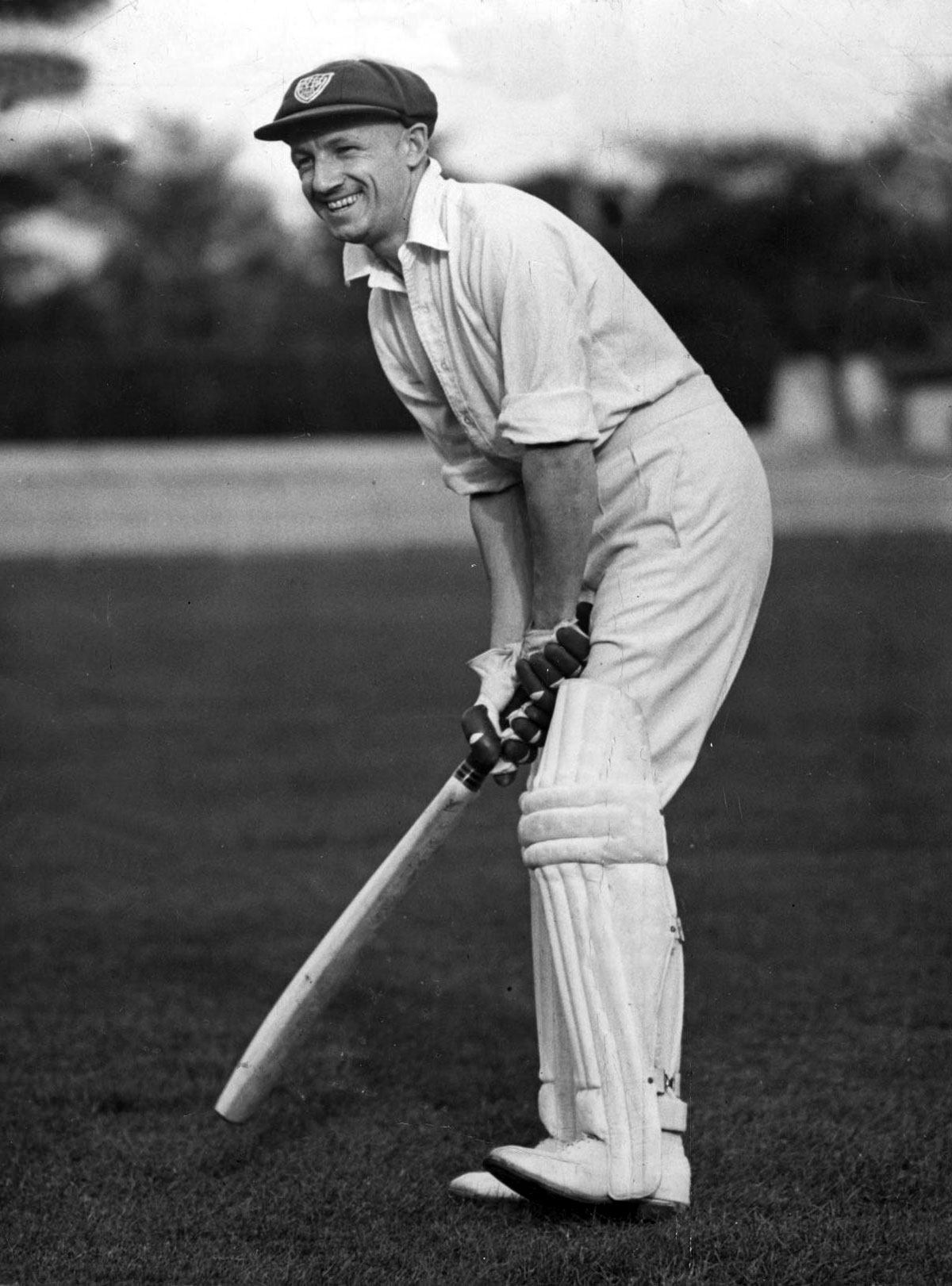

Bradman certainly didn't use the MCC-prescribed grip. Instead, as he wrote in The Art of Cricket, he gripped the bat in a manner that felt "comfortable and natural" to him, forming with the thumb and first finger of each hand two aligned Vs whose central line ran through the splice line of the bat. This meant that when he played a forward defensive, the back of his top hand faced him (and its palm faced the bowler). This neutral grip made it easier to hold the bat with a firm, controlling top hand and a loose bottom hand. As Bradman explained, "it curbs any tendency to follow through [with a strong bottom hand when playing the forward defensive]".

And it was Bradman who, on a balmy, almost cloudless December morning in 1967, advised a 19-year-old Chappell to ditch the MCC grip in favour of the Bradman grip. Chappell heeded the advice for the rest of his long and illustrious career, during which he became renowned throughout the cricket world for his piercing straight drives and cover drives. That advice, acknowledged Chappell in Fierce Focus, "transformed my game".

The Cricket Monthly spoke to seven cricketers of varying ages, three of whom - 68-year-old Chappell, 27-year-old Tim Buszard and 23-year-old Kevin Tissera - are bottom-hand natural, and four of whom - 45-year-old Justin Langer, 41-year-old Hussey, 34-year-old Ed Cowanand 20-year-old Matt Renshaw - are top-hand natural.

For want of a well-established term, this article will refer to batsmen who grip a bat with their naturally dominant hand as their top hand as "top-hand natural" and those who grip a bat with their naturally dominant hand as their bottom hand as "bottom-hand natural".

None of those interviewed - not even Renshaw and Buszard, whose dads are cricket coaches - can recall being expressly directed on how to pick up and grip a bat when they first encountered one. Their earliest cricketing memories are of playing in their backyard, local park and/or beaches with their dads, siblings and mates, using whatever materials were available. For Hussey, those materials initially consisted of nothing more than "a couple of big sticks" as bats and "some little rocks" as balls.

"I certainly don't remember [being directed how to pick up and grip a cricket bat]," says Langer. "It was just a natural instinct [to pick up the bat left-handed]. I can't remember anyone coming out and saying, 'You should be a left-hander or a right-hander.'"

Like many Australian cricketers, Cowan learnt the game in his backyard and at the local park - conveniently located across the road from his family home - with his dad and two older brothers, and didn't encounter formal coaches until he was about 14. He is completely right-handed, but he bats left-handed and has always done so. As an uncoached kid he wasn't conscious of the technicalities of holding a bat; however, as a teenager, he met the late Peter Roebuck, whose coaching and mentorship would have a profound and positive impact on him.

Roebuck firmly believed in having a strong top hand and theorised that batsmen who bat with their naturally dominant hand as their top hand "have accidentally gained an advantage for themselves". He expressed that belief and theory not only in his unequivocal columns in the Age and the Sydney Morning Herald but in his coaching sessions with the teenage Cowan, "consistently letting [him] know that he had an advantage he should be using". Cowan recalls: "Probably at 14, I realised it felt like I had an advantage because it was easier to craft a technique with my top hand being my [naturally] dominant hand."

Langer became aware earlier because, somewhat unusually for an Australian cricketer, he was exposed to coaching at a young age. "When I was… maybe eight or nine years old," he recalls, "my dad brought my first cricket coach around to the backyard and he taught me the basics of the game - his name was Bryn Martin and I still remember him. He used to come on Sunday mornings, talk about the basics and particularly about having a tight-top-hand-and-loose-bottom-hand grip, doing most of my batting through my top hand." That made perfect sense to Langer, who soon realised that that grip came "more naturally" to him because his naturally dominant right hand was his top hand on the bat.

Renshaw, Queensland's rising star, thinks that his small size and consequent lack of physical strength as a junior naturally encouraged him to play with a strong-top-hand-loose-bottom-hand grip because he "couldn't really play the big shots… with that bottom hand". He wasn't conscious of top-hand versus bottom-hand dominance as a kid, but is now of the opinion that his "top-hand dominance definitely helps" him to hit straight.

It should be noted that, although it is easier for top-hand natural batsmen to have a strong-top-hand-loose-bottom-hand grip, numerous great bottom-hand natural Australian Test batsmen - such as Bradman, Steve Waugh and Chappell - have possessed that grip too. Chappell is "a right-hander through and through" and "batted right-handed" with his naturally stronger right hand as his bottom hand, but, he explains: "I know in my batting my top hand [which was my naturally weaker left hand] was my dominant hand. We were fortunate that our father understood [the importance of having a dominant top hand and a very light bottom hand] and drilled that into us from a very early age."

Although, in Australia at least, top-hand natural batsmen are nothing new - Neil Harvey played his first Test, against India at the Adelaide Oval, in January 1948 - it appears that more and more of them are appearing at Test level across the globe. Sports scientists, led by Dr Florian Loffing at the University of Kassel in Germany, recently discovered, after examining every Test cricketer with a batting average of at least 30, that the proportion of them who are top-hand natural has been growing steadily over time: 0% of those who made their Test debut in the 1880s were top-hand natural; for those who made their Test debut this decade, the figure is 33%.

The issue was highlighted by a recent research article in Sports Medicine by Mann, Runswick and Allen. They studied a sample of 43 professional batsmen (who had played first-class and/or international cricket) and 93 amateur batsmen (with less than five years' experience) and found that 40% of those professional batsmen batted with their naturally dominant hand as their top hand, whereas only 9% of the amateur batsmen did so.

Some media reports seemed to suggest that the article concluded that there is a universally "right" batting grip (namely, the top-hand natural grip) and a universally "wrong" batting grip (namely, the bottom-hand natural grip). However, the research itself did not say that. Mann, a capable Australian club cricketer, told the Cricket Monthly that he would "be quite horrified" if the research was misinterpreted to suggest that there is a universally "right" and "wrong" batting stance. "My background is fully in skill acquisition, and I would be the strongest advocate of not using a 'one-size fits all' [technique]. I very much advocate needing to embrace what a player's own technique is, and to not change technique."

That being said, Mann believes that their research "suggests that there is actually an advantage to batting reverse-stance [that is, being top-hand natural] and it does provide a better chance of becoming a professional batsman". That hypothesis is supported by Chappell's postulation that "there is a very good chance" that top-hand natural batsmen have a natural technical advantage, "because it's probably more likely that they are going to use their top hand" in adopting a firm-top-hand-loose-bottom-hand grip.

Natural-hand dominance is unquestionably a salient factor in batsmanship. However, it is only one part of a much larger story. Every single cricketer and coach interviewed for this article underlined that batting is, in Chappell's words, "a whole body exercise". "Human beings", he explains, "are a lever system. The bat is the last lever in the chain." The legs "set up" the lever system and "what you want is a chain reaction where everything happens efficiently and effectively at the right time."

Trent Woodhill is a sports science graduate of the University of New South Wales and one of the most respected batting coaches in Australia, currently working with Melbourne Stars, Royal Challengers Bangalore, and David Warner. He expands the analysis of natural-side dominance to encompass the batsman's entire body, believing that most batsmen have a leg and a hip that they are naturally more comfortable hitting off. As a coach, he always tries to "work out where [an individual batsman's natural] dominance lies" so that he can help the batsman find the technique that's best for him.

Woodhill points out that Virat Kohli is, like Steve Waugh, a bottom-hand natural right-handed batsman who naturally prefers hitting off his back leg. This enables him to play outrageous shots, such as a back-foot square drive off a near yorker just outside off stump, directing the ball behind point with minimal foot movement. "As long as he transfers his weight through his dominant [back] foot," Woodhill says, "he can move his feet as little or as often as he likes."

By contrast Ricky Ponting, a bottom-hand natural right-handed batsman who naturally prefers hitting the ball off his front leg, "just in front of his left knee", could never play the squarish, back-foot drives and cuts that come so naturally to Kohli and Steve Waugh. But he could play other shots that they couldn't, such as the front-foot drive on the up through the covers, and his vicious trademark pull shot against balls that many other batsmen found too full to pull.

A batsman's naturally dominant hitting leg is not necessarily his naturally favoured kicking leg. Warner, Langer and Cowan kick a football with their right foot but are more comfortable hitting the ball off their back - left - foot. By contrast, Steve Smith, Hussey and Renshaw favour kicking a football with, and hitting a ball off, the same leg: their right.

Langer explains that he felt comfortable "pushing off his dominant [right kicking] leg to get back" to play his favourite cut and pull shots. Cowan thinks that his current-day preference for hitting off his back left foot is "just a product of first-class cricket. Even though I'm a front-foot player… [in that] I tell myself to go forward when the ball is released, I think that's so I can push back and play off my back [foot]." He adds that his ten-year-old uncoached self would have favoured hitting off his front foot.

This logic of interconnectedness applies with equal force to the hands themselves. Ian Renshaw, an expert in human movement and skill acquisition at Queensland University of Technology, who has worked extensively with CA as a consultant (and also happens to be Matt Renshaw's father), told the Cricket Monthlythat the batsman's two hands work as a unit. "It's not helpful to look at it as the hands working separately because they don't." Richard Clifton - Glenn Maxwell's personal coach - concurs: the hands "have to work together" as "one unit".

The clearest illustration of this is the straight drive for four or six. As Bradman explained in The Art of Cricket, "there should be a complete follow through" with the bottom hand snapping through fully to finish off the "full-blooded drive" so that, when the stroke is completed, the toe of the bat is pointing at the wicketkeeper's head. Ian Renshaw calls this the "Bradman finish".

Perhaps the finest exemplar of the Bradman finish today is Maxwell, who routinely drives fast bowlers for flat, straight sixes because, as Clifton explains, his top hand "pushes through" and his bottom hand "rips through", giving him both accuracy and power. Maxwell is, like Bradman, bottom-hand natural, which gives him an advantage over top-hand natural batsmen in this particular area - when playing front-foot drives, he finds it easier to rip his naturally stronger bottom hand through to achieve the Bradman finish.

Even the most ardent proponents of the strong-top-hand-loose-bottom-hand grip agree that the bottom hand comes into play for certain shots. As Bradman put it, "the left-hand [that is, the top hand] position must remain firm irrespective of the attempted stroke", but the strength of the bottom hand should vary depending on the shot being played. For example, the forward defensive should be played with a loose bottom hand, whereas the pull shot requires the bottom hand to "predominate" to complete the follow-through.

All four of the top-hand natural batsmen interviewed for this piece - Langer, Hussey, Cowan and Matt Renshaw - recall having good forward defensives as kids. Hussey was "not great" at whipping balls off his pads, and his sweep, pull and hook shots were "not dominant". Langer explains that, as a kid, "I wasn't a powerful hitter through the leg side because I wasn't as strong with my bottom hand" but "I used to use [my loose bottom hand] to control the ball through the leg side, to hit areas and gaps". So "instead of hitting a lot of balls through midwicket, I used to get a lot of balls down to fine leg". Even as a world-class Test batsman, who by the end of his career "swept everything" against spin, Langer found that, "instead of a hard sweep in front of square leg", his sweep shot was "more a lap shot" hit behind square leg. "I tend to just caress it through the leg side," Langer explains, "because I was more top-hand dominant."

Interestingly, despite being a top-hand natural batsman Cowan found that, as a kid, the shot that he played most easily and consistently was the bottom hand-dependent work off his pads. "I think," he says, "that that's a left-handed batsman thing" - junior right-arm bowlers tend to bowl a lot of balls at junior left-handed batsmen's pads - "rather than [a] top- or bottom-hand [thing]".

Cowan and Langer have always favoured pulling and cutting, shots that require their naturally weaker bottom hand to snap through. There are clear environmental and physiological reasons for that - because Cowan and Langer were small for their age, they tended to receive a lot of short balls and had to find a way to counter that; and since they were both naturally more comfortable hitting the ball off their back foot, the pull and hook shots became the natural solutions to that challenge.

Neither Cowan nor Matt Renshaw swept much when they were kids, and Renshaw found it difficult to whip balls off his pads. Even today, Renshaw reckons that his reverse sweep and his switch hit, which derive their power from his naturally stronger top hand, are better than his conventional sweep.

On a sunny Melbourne afternoon in early March, I chatted with the Victorian batsman Peter Handscomb over a coffee on Chapel Street. As we were wrapping up, he shared his thoughts on the next stage of batting's evolution - future generations of batsmen will routinely practise batting both left- and right-handed, and then, come game time, select whichever hand is optimal for a particular bowler.

Two weeks later, in Australia's opening game of the World T20 campaign, Handscomb's friend and Victoria team-mate Maxwell confronted a left-arm orthodox spinner, Mitchell Santner, bowling around the wicket on a slow, gripping pitch in Dharamsala. For the first three deliveries of the 15th over, Maxwell took guard right-handed, then switched to left-handed at around the time Santner jumped into his delivery stride. The left-handed Maxwell worked the first ball with a straight bat through midwicket for two, blocked the second ball (a yorker on off stump) and mishit a sweep off the third ball (a leg-stump full toss) to backward square leg for a single.

On air, Michael Slater was left scratching his head ("What is going on? Aw, again, well, as I said, I reckon he makes batting hard"), but his fellow commentator Tom Moody pointed out that there was an undeniable method to this seeming madness. "Maxwell's thinking, I'm assuming, that he's trying to hit with the spin… " Matt Renshaw didn't watch the game live, but when I explained the match scenario and pitch conditions, he was quick to say: "That would've been probably one of the best options at the time for him."

Thirty-four years earlier, when confronted in the Ranji Trophy by a left-arm orthodox spinner turning it square on a raging turner, Sunil Gavaskar switched to batting left-handed (while continuing to bat right-handed against the other bowlers). Incredibly, he compiled a patient, unbeaten 18 to secure a draw.

Unlike Gavaskar, though, Maxwell only batted left-handed for three balls. A week later, Woodhill - who works with Handscomb and Maxwell at Melbourne Stars - prophesied that, sooner or later "there will be that unique player… who will come out and bat left-handed when the left-arm spinner's on and then when the offspinner comes on, he'll bat right-handed".

Fast forward another three weeks and the scientist David Mann told me of his slightly different, but related, theorem:

"Wherever possible, it's good to actually be able to bat both ways for as long as possible. I mean, at some point you probably do need to specialise. But my initial observation in this whole area was actually of David Warner. So we used to play indoor cricket together when he was young and we would bat together… and he could bat equally well right- or left-handed. Even at that stage [when Warner was about 13 or 14 years old], it wasn't clear which he would actually end up preferring to do."

At least four current elite batsmen in Australia - Warner, Finch, Matt Renshaw and Maxwell - routinely practise batting the other way round. None of the 12 cricketers and coaches interviewed for this piece said they had noticed any Australian kids regularly practising batting both left- and right-handed. However, Hussey observed that thanks to batsmen like Warner and Maxwell, "I probably have noticed kids more often turn around and muck around with batting both left- and right-handed."

In Woodhill's opinion, one factor hindering the evolutionary step of batsmen regularly practising left- and right-handed is current protective equipment: "Right-handed gloves are so different to left-handed gloves, they just haven't got the same protection. And same with the thigh pads as well - small inner [back] thigh pad and a larger [front] one. So until gear is developed to be able to do both, there's a physical risk involved [in batting the other way round]." It came as little surprise when Clifton subsequently said that, as a teenager, Maxwell owned a left-handed thigh pad.

Both Matt Renshaw and Woodhill believe that, at some point in the future, batsmen will regularly switch hands. Indeed, from a broader historical perspective, it's surprising that it hasn't happened already. Highly proficient switch hitters have been part of Major League Baseball since at least the late 19th century, and prior to the 1990s, many of Australia's finest batsmen, from Victor Richardson to Harvey to Norm O'Neill to Bill Lawry to Ian Chappell to Greg Chappell to Border to Brad Hodge, spent their winters playing high-level baseball.

If the latest generation of Australian batsmen has a standard-bearer, it is the 20-year-old Renshaw, the fifth highest run scorer in last summer's Shield, runner-up for the Shield Player of the Season award, and the youngest batsman picked in this winter's Australia A squad. The left-handed Renshaw is, in many senses, a classical opener. He is patient and enjoys batting for long periods. He doesn't hold a Big Bash contract, is yet to make his List A debut for Queensland, and his season strike rate of 40.95 was the lowest of last summer's top ten Shield run scorers. Those facts are fairly well known.

What is less well known is that Renshaw has switch hit a six at Lord's, a shot that came as little surprise to those who know that he has been practising batting right-handed since he was a boy. "I can't really remember whether it was [my idea] or Dad's," he says. "I can just remember watching people play reverse sweeps and I thought that would be pretty cool. And so I started trying to bat right-handed."

He has had both the switch hit and the reverse sweep in his armoury since he was a teenager. Of the two, he is "more comfortable playing the reverse sweep because when you go for the switch hit, you have to swap everything and the bowler can change where he is going to bowl it". He'll only play the higher risk switch hit if there is a good reason to do so. He did it at Lord's because "it was an offspinner [bowling] to a short boundary on the off side".

Renshaw is yet to see any batsman do what Handscomb predicted that the next generation would do - change hands during a game to suit the bowler they're facing - but says, without skipping a beat, "I've definitely talked about it with Dad".

Nerves are on edge as wickets tumble and it's your turn to bat next © Getty Images

Nerves are on edge as wickets tumble and it's your turn to bat next © Getty Images Captains and coaches can seek to arrest the collapse by talking to the remaining batsmen about their preparation and the importance of playing naturally © Getty Images

Captains and coaches can seek to arrest the collapse by talking to the remaining batsmen about their preparation and the importance of playing naturally © Getty Images Going up: Sehwag constantly turned traditional batting concepts on their head © AFP

Going up: Sehwag constantly turned traditional batting concepts on their head © AFP Paul Harris ended up the loser in his contest with Sehwag in 2008 © Getty Images

Paul Harris ended up the loser in his contest with Sehwag in 2008 © Getty Images Fury Road: Sehwag set up India's record chase against England in Chennai in 2008 © AFP

Fury Road: Sehwag set up India's record chase against England in Chennai in 2008 © AFP