It may sound like off-the-wall leftiness, but there are clear and convincing arguments for a nationalised mobile phone network

Mobile phone companies put profit before the needs of the consumer. Photograph: Alamy

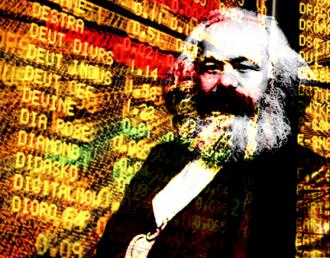

Nationalisation is a taboo among the political and media elite, its mere mention guaranteed to provoke near-instantaneous shrieks of "dinosaur!" and "go back to the 1970s". Imagine the Establishment's horror, then, when a succession of recent polls found that nearly seven out of 10 Britons wanted the renationalisation of energy, and two-thirds of the electorate wanted rail and Royal Mail back in public hands. Even Ukip voters – those notorious bastions of pinko leftiness – overwhelmingly backed the renationalisation of key utilities. While our political overlords are besotted with Milton Friedman, on many issues the public seem to be lodged somewhere between John Maynard Keynes and Karl Marx.

Previously state-owned services are one thing: but what about the mobile phone network? Even the very suggestion is inviting ridicule. But if people are so keen for public ownership of rail, why is the case any weaker for mobile phones? They are a natural monopoly, and the fragmentation of the telecommunications network is inefficient. Their service is often poor because they put profit ahead of the needs of the consumer. And rather than being the product of a dynamic free market and individual plucky entrepreneurs, their technological success owes everything to the public sector. It might seem like barking leftiness on speed, but the arguments for nationalising phone networks are less absurd than they might appear.

The eternal irritation of any mobile phone user is the signal blackspot. They affect everyone. Even David Cameron has had to return early from his holidays in Cornwall because of problems with signal "not-spots". Nor is it only a problem for people in rural areas. Richard Brown lives at the top of a hill in Brighton, and he can't get a signal withVodafone, despite its database claiming excellent coverage. "So for £100 I bought a 'Sure Signal' device – or in other words paid £100 to enable Vodafone to deliver me the core service that I am already paying upwards of £30 a month for." It plugs into the router and drains power, but seems to make little difference.

In his south London flat, EE customer Ben Goddard's mobile phone almost always registers no bars. With missed calls from hospitals and family members, he's been forced to install a house phone. "Zero signal in east London," says fellow EE user Dom O'Hanlon. "No attempt to fix, help or offer customer service." EE seem to have abandoned its earlier incarnation as 'Everything Everywhere' because it was so widely mocked as 'Nothing Nowhere'. When Ben Parker switched from EE to Vodafone, he found that his signal did improve, but his data access died, forcing him to depend on Wi-Fi.

If you have tried to deal with the customer service arm of the mobile phone giants, then please do not read on, because you will only relive traumas you would rather forget. After Grace Garland was signed up to EE from her Orange contract, her 4G and internet access all but vanished for several months. Errors at EE's end left her being charged double, and its system believed she had run out of her data allowance, leaving her with no access to crucial work emails. "No one took my concerns seriously," she says. "They told me they had actually subcontracted a lot of their technical support to outside parties who can only be contacted by them by email, making everything slow and ineffectual." Of course, mobile phone companies do not provide detailed data about their national coverage, leaving customers to choose on the basis of factors such as price.

According to OpenSignal – a company that is ingeniously working out national signal coverage by tracking data from mobile users – the average British user has no signal 15% of the time. And here is where the point about a natural monopoly creeps in. Mobile phone companies build their masts, but don't want to share them with their competitors. That means that rather than having a network that reflects people's needs, we are constantly zipping past masts we are locked out of. In many rural areas, mobile phone companies are simply making the decision that there are not enough people to justify building more masts. Profit is prioritised over building an effective network that gives all citizens access.

Signal failure … a woman struggles to make a call in Hythe, Kent. Photograph: Alamy

Signal failure … a woman struggles to make a call in Hythe, Kent. Photograph: Alamy

To be fair to the government, it is proposing action to compel companies to share masts. But OpenSignal's Samuel Johnson says that this would only cover phone calls and text messages, not data, and would reduce our time without signal to about 7%. Why not force them to share all data? "Well, it'd be bad for competition, because it would hit their profits," he says. Not only that, but even if the government's modest measures are implemented, the potential financial hit to mobile phone companies would deter them from clamping down on the final 7%.

Customers are ripped off in other ways. The former Daily Telegraph journalist George Pitcher has pointed out that the typical "free phone when you sign a long contract" offer is a scam. In a typical £32-a-month contract spread over two years, you're coughing up £768, even though the phone is worth just £200. Get a £15-a-month SIM card-only deal and buy a £10 mobile off eBay instead, he suggests, and you'll save £400. "Perhaps the mobile phone companies could be nationalised and given to the banks?" he concludes. Last part aside, Pitcher has it in one. And then there's the derisory cost to the company of sending snippets of data such as text messages – which can cost the user 14p a pop. Last year, Citizens Advice received a whopping 28,000 complaints about mobile phones, often from customers who could not be released from contracts even if there was no signal in their area.

Neither are mobile phones themselves triumphs of the private sector, or even close. "It's not far-fetched to suggest nationalisation," says economics professor Mariana Mazzucato, "because these companies aren't the result of some individual entrepreneur in the garage. It was all state-funded from the start." As I write this, I fiddle occasionally with my iPhone: in her hugely influential book The Entrepreneurial State, Mazzucato looks at how its key components, like touchscreen technology, Siri and GPS are the products of public-sector research. That goes for the internet, too – the child of the US military-industrial complex and the work of Sir Tim Berners-Lee at the state-run European research organisation Cern in Geneva.

"It's actually the classic case of economies of scale, or a natural monopoly, and the decision you'd have to make is whether it's one firm or the state running the whole thing," says Mazzucato. "When you chop it up, you lose the benefits of cost and efficiency from having one operator." Many network providers spend more money on share buybacks than research and development, retarding further technological progress in the name of profit. And then there's Vodafone, which has become one of the key targets of the anti-tax avoidance movement. It's cheeky, really: leave the state to fund the technology your business relies on, and then do everything you can to avoid paying anything back.

There are many reasons why a fragmented mobile phone network is bad for the consumer. Dr Oliver Holland of King's College London's Centre for Telecommunications Research sympathises with the idea of a nationalised network on technical grounds. This is how he explains it. Each mobile phone company is allotted a slice of the frequency spectrum. But at any given time, lots of customers belonging to one company may be using their mobile phones. "You will probably have a reduction in the quality of the service, because they're all competing for the spectrum." Customers belonging to another company may be using the service less at the same time, leaving their slice of the spectrum to go to waste when others need it. "If you had just one body, instead of dividing the spectrum into chunks, they can use it more efficiently," he says.

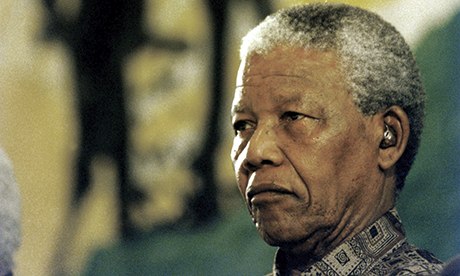

The case for nationalising mobile phone companies is actually pretty overwhelming. It would mean an integrated network, with masts serving customers on the basis of need, rather than subordinating the needs of users to the needs of shareholders. Profits could be reinvested in research and development, as well as developing effective customer services. Rip-off practices could be eradicated. It doesn't have to be run by a bunch of bureaucrats: consumers could elect representatives on to the management board to make sure the publicly run company is properly accountable. Neither does nationalisation have to be costly: Clement Attlee's postwar Labour government pulled it off by swapping shares for government bonds. So yes, it might sound far-fetched, the sort of proposal that lends itself to endless satire from the triumphalist neoliberal right. But next time you're yelling at your signal-free mobile phone, it might not seem so wacky after all.