There is a question that was never put to the leaders of the campaign for Brexit and has not, as far as I’m aware, been put to the prime minister since her conversion to the cause. It is this: what will you do on the morning of formal separation from the EU that you could not have done the day before?

What restored freedom, what action hitherto proscribed by the tyrannical bureaucrats of Brussels, will you indulge as the sparkling English wine is uncorked? Bend a banana, perhaps. Or catch the Eurostar to Paris and savour the sensation of no longer having the automatic right to work there. Oh! Pleasant exercise of hope and joy! … Bliss it will be in that dawn to be alive. Right?

Brexit enthusiasts will complain that my question is unfair. Objections to EU membership were all about democracy, sovereignty and long-term economic opportunity: not pleasures that can be consumed overnight. And while that might be so, it is also true that people tend to vote for things in expectation of tangible benefits. A weekly dividend of £350m for the NHS, for example. So the unlikelihood of quick gratification for leave voters is a problem.

Theresa May identifies a deeper imperative to Brexit than was written on the referendum ballot paper. She hears a collective cry of rage against the economic and political status quo, requiring radical change on multiple fronts. So, in parallel with the prime minister’s plan for a “clean break” from the rest of Europe, Downing Street is thinking of ways to address grievances that generated demand for Brexit in the first place: stagnant wages; anxiety that living standards have peaked and that the next generation is being shafted; the demoralising experience of working all hours without saving a penny.

Government thinking on these issues has so far yielded a modest harvest. Last week’s housing white paper was meant to address a chronic shortage of homes by nudging councils towards quicker approval of new developments. Last month saw the launch of an industrial strategy, embracing state activism to nurture growth in under-resourced sectors and neglected regions. Last year May appointed Matthew Taylor, formerly head of Tony Blair’s policy unit, to lead a review into modern employment practices – the decline of the stable, rewarding full-time career and its replacement by poorly paid, insecure casual servitude.

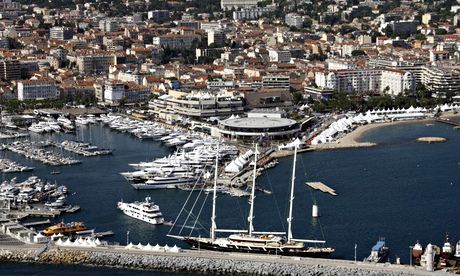

‘Ed Miliband’s focus on the squeezed middle anticipated Theresa May’s promise to help those who are just-about-managing.’ Photograph: Alamy

A notable feature of this non-Brexit agenda is how closely it tracks arguments made by Ed Miliband in the last parliament. The former Labour leader had a whole thesis about the structural failings of British capitalism and how it corroded people’s confidence in the future, leaving them anxious and angry. His focus on the “squeezed middle” anticipated May’s promise to help those who are “just-about-managing”. Miliband’s calls for state intervention in failing markets were derided by the Tories as socialist delusion at the time, but he opened rhetorical doors through which May is now tentatively stepping. Last week’s housing paper even used a forgotten policy that Labour had launched in 2013 – a “Use it or lose it” threat to developers who hoard land without building on it.

Meanwhile, Downing Street has taken a close interest in the commission on economic justice set up by the Institute for Public Policy Research, a thinktank that provided regular policymaking services for Labour in the days before its capture by Corbynism. The commission was recently invited to give a presentation to May’s leading policy advisers inside No 10.

Were it not for Brexit’s domination of political debate, May’s eschewal of conventional left-right dividing lines – her willingness to jettison Thatcherite orthodoxies – might have attracted more notice. But then, as the old Yiddish saying goes, if my granny had balls she’d be my grandpa. The idea that there is some parallel realm of politics that May can develop and for which she will be remembered alongside her EU negotiation is delusional. Timid little steps on housing, industrial strategy and job security are not going to get the prime minister to the promised land of fairness and opportunity in time for Brexit day. And she insists on a diversion to set up more grammar schools along the way, despite nearly every expert in the field warning that educational selection closes more avenues to social mobility than it opens.

Someone will have to level with the country. The dawn of Brexit promises no freedom that wasn’t there the day before

Even on immigration the government cannot meet expectations raised by the leave campaign. There will still be new people arriving because businesses will insist on a capacity to hire from abroad. Millions who arrived in Britain over recent decades, and their children born as British citizens, will stay because the country is their home. Even the most draconian border regime cannot restore the ethnic homogeneity for which some nostalgic Brexiteers pine.

At some point someone is going to have to level with the country. Much of what leave voters were promised is unavailable because the EU was never responsible for a lot of things that made them angry. The dawn of Brexit promises no significant freedom or opportunity that wasn’t there the day before. It isn’t a message that ex-remainers can deliver, for all the reasons that scuppered their campaign last year. It sounded patronising before the referendum and the tone isn’t improved by bitterness in defeat.

None of the original leave campaigners will dare admit their dishonesty in making Brussels the scapegoat for every conceivable social and economic ill. There is no point expecting Boris Johnson or Michael Gove to embark on a self-critical journey of public-expectation management. Far more likely they will be drawn deeper into the old lie: someone must be held responsible when Brexit does not unblock the sluices of wealth and opportunity; when the milk and honey refuse to flow. The obvious candidates are foreigners and fifth columnists – EU governments that negotiate in bad faith; alien interlopers who drain public services; unpatriotic “remoaners” talking the country down.

The question then is whether the prime minister will go along with that game. She has managed so far to sustain the pretence that dealing with the failure of Britain’s economy to share its bounties fairly and quitting the EU are kind of the same thing. If it turns out that they aren’t, and one ambition obstructs the other, who will she blame?

Were it not for Brexit’s domination of political debate, May’s eschewal of conventional left-right dividing lines – her willingness to jettison Thatcherite orthodoxies – might have attracted more notice. But then, as the old Yiddish saying goes, if my granny had balls she’d be my grandpa. The idea that there is some parallel realm of politics that May can develop and for which she will be remembered alongside her EU negotiation is delusional. Timid little steps on housing, industrial strategy and job security are not going to get the prime minister to the promised land of fairness and opportunity in time for Brexit day. And she insists on a diversion to set up more grammar schools along the way, despite nearly every expert in the field warning that educational selection closes more avenues to social mobility than it opens.

Someone will have to level with the country. The dawn of Brexit promises no freedom that wasn’t there the day before

Even on immigration the government cannot meet expectations raised by the leave campaign. There will still be new people arriving because businesses will insist on a capacity to hire from abroad. Millions who arrived in Britain over recent decades, and their children born as British citizens, will stay because the country is their home. Even the most draconian border regime cannot restore the ethnic homogeneity for which some nostalgic Brexiteers pine.

At some point someone is going to have to level with the country. Much of what leave voters were promised is unavailable because the EU was never responsible for a lot of things that made them angry. The dawn of Brexit promises no significant freedom or opportunity that wasn’t there the day before. It isn’t a message that ex-remainers can deliver, for all the reasons that scuppered their campaign last year. It sounded patronising before the referendum and the tone isn’t improved by bitterness in defeat.

None of the original leave campaigners will dare admit their dishonesty in making Brussels the scapegoat for every conceivable social and economic ill. There is no point expecting Boris Johnson or Michael Gove to embark on a self-critical journey of public-expectation management. Far more likely they will be drawn deeper into the old lie: someone must be held responsible when Brexit does not unblock the sluices of wealth and opportunity; when the milk and honey refuse to flow. The obvious candidates are foreigners and fifth columnists – EU governments that negotiate in bad faith; alien interlopers who drain public services; unpatriotic “remoaners” talking the country down.

The question then is whether the prime minister will go along with that game. She has managed so far to sustain the pretence that dealing with the failure of Britain’s economy to share its bounties fairly and quitting the EU are kind of the same thing. If it turns out that they aren’t, and one ambition obstructs the other, who will she blame?