A S Paneerselvan in The Hindu

Analysing data without providing sufficient context is dangerous

An inherent challenge in journalism is to meet deadlines without compromising on quality, while sticking to the word limit. However, brevity takes a toll when it comes to reporting on surveys, indexes, and big data. Let me examine three sets of stories which were based on surveys and carried prominently by this newspaper, to understand the limits of presenting data without providing comprehensive context.

Three reports

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), Oxfam’s report titled ‘Reward Work, Not Wealth’, and the World Bank’s ease of doing business (EoDB) rankings have been widely reported, commented on, and editorialised. In most cases, the numbers and rankings were presented as neutral evaluations; they were not seen as data originating from institutions that have political underpinnings. Data become meaningful only when the methodology of data collection is spelt out in clear terms.

Every time I read surveys, indexes, and big data, I look for at least three basic parameters to understand the numbers: the sample size, the sample questionnaire, and the methodology. The sample size used indicates the robustness of the study, the questionnaire reveals whether there are leading questions, and the methodology reveals the rigour in the study. As a reporter, there were instances where I failed to mention these details in my resolve to stick to the word limit. Those were my mistakes.

The ASER study covering specific districts in States is about children’s schooling status. It attempts to measure children’s abilities with regard to basic reading and writing. It is a significant study as it gives us an insight into some of the problems with our educational system. However, we must be aware of the fact that these figures are restricted only to the districts in which the survey was conducted. It cannot be extrapolated as a State-wide sample, nor is it fair to rank States based on how specific districts fare in the study. A news item, “Report highlights India’s digital divide” (Jan. 19, 2018), conflated these figures.

For instance, the district surveyed in Kerala was Ernakulam, which is an urban district; in West Bengal it was South 24 Parganas, a complex district that stretches from metropolitan Kolkata to remote villages at the mouth of the Bay of Bengal. How can we compare these two districts with Odisha’s Khordha, Jharkhand’s Purbi Singhbhum and Bihar’s Muzaffarpur? It could be irresistible for a reporter, who accessed the data, to paint a larger picture based on these specific numbers. But we may not learn anything when we compare oranges and apples.

Questionable methodology

Oxfam, in the ‘Reward Work, Not Wealth’ report, used a methodology that has been questioned by many economists. Inequality is calculated on the basis of “net assets”. The economists point out that in this method, the poorest are not those living with very little resources, but young professionals who own no assets and with a high educational loan. Inequality is the elephant in the room which we cannot ignore. But Oxfam’s figures seem to mimic the huge notional loss figures put out by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India. Readers should know that Oxfam’s study has drawn its figures from disparate sources such as the Global Wealth Report by Credit Suisse, the Forbes’ billionaires list, adjusting last year’s figure using the average annual U.S. Consumer Price Index inflation rate from the U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics, the World Bank’s household survey data, and an online survey in 10 countries.

When the World Bank announced the EoDB index last year, there was euphoria in India. However, this newspaper’s editorial “Moving up” (Nov. 2, 2017), which looked at India’s surge in the latest World Bank ranking from the 130th position to the 100th in a year, cautioned and asked the government, which has great orators in its ranks, to be a better listener. In hindsight, this position was vindicated when the World Bank’s chief economist, Paul Romer, said that he could no longer defend the integrity of changes made to the methodology and that the Bank would recalculate the national rankings of business competitiveness going back to at least four years. Readers would have appreciated the FAQ section (“Recalculating ease of doing business”, Jan. 25) that explained this controversy in some detail, had it looked at India’s ranking using the old methodology.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label liar. Show all posts

Showing posts with label liar. Show all posts

Wednesday, 31 January 2018

Friday, 7 October 2016

Lies, fearmongering and fables: that’s our democracy

George Monbiot in The Guardian

What if democracy doesn’t work? What if it never has and never will? What if government of the people, by the people, for the people is a fairytale? What if it functions as a justifying myth for liars and charlatans?

There are plenty of reasons to raise these questions. The lies, exaggerations and fearmongering on both sides of the Brexit non-debate; the xenophobic fables that informed the Hungarian referendum; Donald Trump’s ability to shake off almost any scandal and exposure; the election of Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, who gleefully compares himself to Hitler: are these isolated instances or do they reveal a systemic problem?

Democracy for Realists, published earlier this year by the social science professors Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels, argues that the “folk theory of democracy” – the idea that citizens make coherent and intelligible policy decisions, on which governments then act – bears no relationship to how it really works. Or could ever work.

Voters, they contend, can’t possibly live up to these expectations. Most are too busy with jobs and families and troubles of their own. When we do have time off, not many of us choose to spend it sifting competing claims about the fiscal implications of quantitative easing. Even when we do, we don’t behave as the theory suggests.

2.8 million voters punished Al Gore for the floods and droughts of 2000 – ironic, given his position on climate change

Our folk theory of democracy is grounded in an Enlightenment notion of rational choice. This proposes that we make political decisions by seeking information, weighing the evidence and using it to choose good policies, then attempting to elect a government that will champion those policies. In doing so, we compete with other rational voters, and seek to reach the unpersuaded through reasoned debate.

In reality, the research summarised by Achen and Bartels suggests, most people possess almost no useful information about policies and their implications, have little desire to improve their state of knowledge, and have a deep aversion to political disagreement. We base our political decisions on who we are rather than what we think. In other words, we act politically – not as individual, rational beings but as members of social groups, expressing a social identity. We seek out the political parties that seem to correspond best to our culture, with little regard to whether their policies support our interests. We remain loyal to political parties long after they have ceased to serve us.

Of course, shifts do happen, sometimes as a result of extreme circumstances, sometimes because another party positions itself as a better guardian of a particular cultural identity. But they seldom involve a rational assessment of policy.

The idea that parties are guided by policy decisions made by voters also seems to be a myth; in reality, the parties make the policies and we fall into line. To minimise cognitive dissonance – the gulf between what we perceive and what we believe – we either adjust our views to those of our favoured party or avoid discovering what the party really stands for. This is how people end up voting against their interests.

We are suckers for language. When surveys asked Americans whether the federal government was spending too little on “assistance to the poor”, 65% agreed. But only 25% agreed that it was spending too little on “welfare”. In the approach to the 1991 Gulf war, nearly two-thirds of Americans said they were willing to “use military force”; less than 30% were willing to “go to war”.

Even the less ambitious notion of democracy – that it’s a means by which people punish or reward governments – turns out to be divorced from reality. We remember only the past few months of a government’s performance (a bias known as “duration neglect”) and are hopeless at correctly attributing blame. A great white shark that killed five people in July 1916 caused a 10% swing against Woodrow Wilson in the beach communities of New Jersey. In 2000, according to analysis by the authors 2.8 million voters punished the Democrats for the floods and droughts that struck that year. Al Gore, they say, lost Arizona, Louisiana, Nevada, Florida, New Hampshire, Tennessee and Missouri as a result – which is ironic given his position on climate change.

The obvious answer is better information and civic education. But this doesn’t work either. Moderately informed Republicans were more inclined than Republicans with the least information to believe that Bill Clinton oversaw an increase in the budget deficit (it declined massively). Why? Because, unlike the worst informed, they knew he was a Democrat. The tiny number of people with a very high level of political information tend to use it not to challenge their own opinions but to rationalise them. Political knowledge, Achen and Bartels argue, “enhances bias”.

Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems

Direct democracy – referendums and citizens’ initiatives – seems to produce even worse results. In the US initiatives are repeatedly used by multimillion-dollar lobby groups to achieve results that state legislatures won’t grant them. They tend to replace taxes with user fees, stymie the redistribution of wealth and degrade public services. Whether representative or direct, democracy comes to be owned by the elites.

This is not to suggest that it has no virtues; just that those it does have are not those we principally ascribe to it. It allows governments to be changed without bloodshed, limits terms in office, and ensures that the results of elections are widely accepted. Sometimes public attribution of blame will coincide with reality, which is why you don’t get famines in democracies.

In these respects it beats dictatorship. But is this all it has to offer? A weakness of Democracy for Realists is that most of its examples are drawn from the US, and most of those are old. Had the authors examined popular education groups in Latin America, participatory budgets in Brazil and New York, the fragmentation of traditional parties in Europe and the movement that culminated in Bernie Sanders’ near miss, they might have discerned more room for hope. This is not to suggest that the folk theory of democracy comes close to reality anywhere, but that the situation is not as hopeless as they propose.

Persistent, determined, well-organised groups can bring neglected issues to the fore and change political outcomes. But in doing so they cannot rely on what democracy ought to be. We must see it for what it is. And that means understanding what we are.

What if democracy doesn’t work? What if it never has and never will? What if government of the people, by the people, for the people is a fairytale? What if it functions as a justifying myth for liars and charlatans?

There are plenty of reasons to raise these questions. The lies, exaggerations and fearmongering on both sides of the Brexit non-debate; the xenophobic fables that informed the Hungarian referendum; Donald Trump’s ability to shake off almost any scandal and exposure; the election of Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, who gleefully compares himself to Hitler: are these isolated instances or do they reveal a systemic problem?

Democracy for Realists, published earlier this year by the social science professors Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels, argues that the “folk theory of democracy” – the idea that citizens make coherent and intelligible policy decisions, on which governments then act – bears no relationship to how it really works. Or could ever work.

Voters, they contend, can’t possibly live up to these expectations. Most are too busy with jobs and families and troubles of their own. When we do have time off, not many of us choose to spend it sifting competing claims about the fiscal implications of quantitative easing. Even when we do, we don’t behave as the theory suggests.

2.8 million voters punished Al Gore for the floods and droughts of 2000 – ironic, given his position on climate change

Our folk theory of democracy is grounded in an Enlightenment notion of rational choice. This proposes that we make political decisions by seeking information, weighing the evidence and using it to choose good policies, then attempting to elect a government that will champion those policies. In doing so, we compete with other rational voters, and seek to reach the unpersuaded through reasoned debate.

In reality, the research summarised by Achen and Bartels suggests, most people possess almost no useful information about policies and their implications, have little desire to improve their state of knowledge, and have a deep aversion to political disagreement. We base our political decisions on who we are rather than what we think. In other words, we act politically – not as individual, rational beings but as members of social groups, expressing a social identity. We seek out the political parties that seem to correspond best to our culture, with little regard to whether their policies support our interests. We remain loyal to political parties long after they have ceased to serve us.

Of course, shifts do happen, sometimes as a result of extreme circumstances, sometimes because another party positions itself as a better guardian of a particular cultural identity. But they seldom involve a rational assessment of policy.

The idea that parties are guided by policy decisions made by voters also seems to be a myth; in reality, the parties make the policies and we fall into line. To minimise cognitive dissonance – the gulf between what we perceive and what we believe – we either adjust our views to those of our favoured party or avoid discovering what the party really stands for. This is how people end up voting against their interests.

We are suckers for language. When surveys asked Americans whether the federal government was spending too little on “assistance to the poor”, 65% agreed. But only 25% agreed that it was spending too little on “welfare”. In the approach to the 1991 Gulf war, nearly two-thirds of Americans said they were willing to “use military force”; less than 30% were willing to “go to war”.

Even the less ambitious notion of democracy – that it’s a means by which people punish or reward governments – turns out to be divorced from reality. We remember only the past few months of a government’s performance (a bias known as “duration neglect”) and are hopeless at correctly attributing blame. A great white shark that killed five people in July 1916 caused a 10% swing against Woodrow Wilson in the beach communities of New Jersey. In 2000, according to analysis by the authors 2.8 million voters punished the Democrats for the floods and droughts that struck that year. Al Gore, they say, lost Arizona, Louisiana, Nevada, Florida, New Hampshire, Tennessee and Missouri as a result – which is ironic given his position on climate change.

The obvious answer is better information and civic education. But this doesn’t work either. Moderately informed Republicans were more inclined than Republicans with the least information to believe that Bill Clinton oversaw an increase in the budget deficit (it declined massively). Why? Because, unlike the worst informed, they knew he was a Democrat. The tiny number of people with a very high level of political information tend to use it not to challenge their own opinions but to rationalise them. Political knowledge, Achen and Bartels argue, “enhances bias”.

Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems

Direct democracy – referendums and citizens’ initiatives – seems to produce even worse results. In the US initiatives are repeatedly used by multimillion-dollar lobby groups to achieve results that state legislatures won’t grant them. They tend to replace taxes with user fees, stymie the redistribution of wealth and degrade public services. Whether representative or direct, democracy comes to be owned by the elites.

This is not to suggest that it has no virtues; just that those it does have are not those we principally ascribe to it. It allows governments to be changed without bloodshed, limits terms in office, and ensures that the results of elections are widely accepted. Sometimes public attribution of blame will coincide with reality, which is why you don’t get famines in democracies.

In these respects it beats dictatorship. But is this all it has to offer? A weakness of Democracy for Realists is that most of its examples are drawn from the US, and most of those are old. Had the authors examined popular education groups in Latin America, participatory budgets in Brazil and New York, the fragmentation of traditional parties in Europe and the movement that culminated in Bernie Sanders’ near miss, they might have discerned more room for hope. This is not to suggest that the folk theory of democracy comes close to reality anywhere, but that the situation is not as hopeless as they propose.

Persistent, determined, well-organised groups can bring neglected issues to the fore and change political outcomes. But in doing so they cannot rely on what democracy ought to be. We must see it for what it is. And that means understanding what we are.

Sunday, 26 June 2016

There are liars and then there’s Boris Johnson and Michael Gove

Nick Cohen in The Guardian

The Brexit figureheads had no plan besides exploiting populist fears and dismissing experts who rubbished their thinking

The Brexit figureheads had no plan besides exploiting populist fears and dismissing experts who rubbished their thinking

‘Prospered by treating public life as a game’: Boris Johnson leaves his home in Oxfordshire on Saturday. Photograph: Peter Nicholls/Reuters

Where was the champagne at the Vote Leave headquarters? The happy tears and whoops of joy? If you believed Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, the Brexit vote was a moment of national liberation, a day that Nigel Farage said our grateful children would celebrate with an annual bank holiday.

Johnson and Gove had every reason to celebrate. The referendum campaign showed the only arguments that matter now in England are on the right. With the Labour leadership absent without leave and the Liberal Democrats and Greens struggling to be heard, the debate was between David Cameron and George Osborne, defending the status quo, and the radical right, demanding its destruction. Johnson and Gove won a dizzying victory with the potential to change every aspect of national life, from workers’ rights to environmental protection.

Yet they gazed at the press with coffin-lid faces and wept over the prime minister they had destroyed. David Cameron was “brave and principled”, intoned Johnson. “A great prime minister”, muttered Gove. Like Goneril and Regan competing to offer false compliments to Lear, they covered the leader they had doomed with hypocritical praise. No one whoops at a funeral, especially not mourners who are glad to see the back of the deceased. But I saw something beyond hypocrisy in those frozen faces: the fear of journalists who have been found out.

The media do not damn themselves, so I am speaking out of turn when I say that if you think rule by professional politicians is bad wait until journalist politicians take over. Johnson and Gove are the worst journalist politicians you can imagine: pundits who have prospered by treating public life as a game. Here is how they play it. They grab media attention by blaring out a big, dramatic thought. An institution is failing? Close it. A public figure blunders? Sack him. They move from journalism to politics, but carry on as before. When presented with a bureaucratic EU that sends us too many immigrants, they say the answer is simple, as media answers must be. Leave. Now. Then all will be well.

Johnson and Gove carried with them a second feature of unscrupulous journalism: the contempt for practical questions. Never has a revolution in Britain’s position in the world been advocated with such carelessness. The Leave campaign has no plan. And that is not just because there was a shamefully under-explored division between the bulk of Brexit voters who wanted the strong welfare state and solid communities of their youth and the leaders of the campaign who wanted Britain to become an offshore tax haven. Vote Leave did not know how to resolve difficulties with Scotland, Ireland, the refugee camp at Calais, and a thousand other problems, and did not want to know either.

It responded to all who predicted the chaos now engulfing us like an unscrupulous pundit who knows that his living depends on shutting up the experts who gainsay him. For why put the pundit on air, why pay him a penny, if experts can show that everything he says is windy nonsense? The worst journalists, editors and broadcasters know their audiences want entertainment, not expertise. If you doubt me, ask when you last saw panellists on Question Time who knew what they were talking about.

Naturally, Michael Gove, former Times columnist, responded to the thousands of economists who warned he was taking an extraordinary risk with the sneer that will follow him to his grave: “People in this country have had enough of experts.” He’s being saying the same for years.

If sneers won’t work, the worst journalists lie. The Times fired Johnson for lying to its readers. Michael Howard fired Johnson for lying to him. When he’s cornered, Johnson accuses others of his own vices, as unscrupulous journalists always do. Those who question him are the true liars, he blusters, whose testimony cannot be trusted because, as he falsely said of the impeccably honest chairman of the UK Statistics Authority, they are “stooges”.

The Vote Leave campaign followed the tactics of the sleazy columnist to the letter. First, it came out with the big, bold solution: leave. Then it dismissed all who raised well-founded worries with “the country is sick of experts”. Then, like Johnson the journalist, it lied.

I am not going to be over-dainty about mendacity. Politicians, including Remain politicians lie, as do the rest of us. But not since Suez has the nation’s fate been decided by politicians who knowingly made a straight, shameless, incontrovertible lie the first plank of their campaign. Vote Leave assured the electorate it would reclaim a supposed £350m Brussels takes from us each week. They knew it was a lie. Between them, they promised to spend £111bn on the NHS, cuts to VAT and council tax, higher pensions, a better transport system and replacements for the EU subsidies to the arts, science, farmers and deprived regions. When boring experts said that, far from being rich, we would face a £40bn hole in our public finances, Vote Leave knew how to fight back. In Johnsonian fashion, it said that the truth tellers were corrupt liars in Brussels’ pocket.

Where was the champagne at the Vote Leave headquarters? The happy tears and whoops of joy? If you believed Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, the Brexit vote was a moment of national liberation, a day that Nigel Farage said our grateful children would celebrate with an annual bank holiday.

Johnson and Gove had every reason to celebrate. The referendum campaign showed the only arguments that matter now in England are on the right. With the Labour leadership absent without leave and the Liberal Democrats and Greens struggling to be heard, the debate was between David Cameron and George Osborne, defending the status quo, and the radical right, demanding its destruction. Johnson and Gove won a dizzying victory with the potential to change every aspect of national life, from workers’ rights to environmental protection.

Yet they gazed at the press with coffin-lid faces and wept over the prime minister they had destroyed. David Cameron was “brave and principled”, intoned Johnson. “A great prime minister”, muttered Gove. Like Goneril and Regan competing to offer false compliments to Lear, they covered the leader they had doomed with hypocritical praise. No one whoops at a funeral, especially not mourners who are glad to see the back of the deceased. But I saw something beyond hypocrisy in those frozen faces: the fear of journalists who have been found out.

The media do not damn themselves, so I am speaking out of turn when I say that if you think rule by professional politicians is bad wait until journalist politicians take over. Johnson and Gove are the worst journalist politicians you can imagine: pundits who have prospered by treating public life as a game. Here is how they play it. They grab media attention by blaring out a big, dramatic thought. An institution is failing? Close it. A public figure blunders? Sack him. They move from journalism to politics, but carry on as before. When presented with a bureaucratic EU that sends us too many immigrants, they say the answer is simple, as media answers must be. Leave. Now. Then all will be well.

Johnson and Gove carried with them a second feature of unscrupulous journalism: the contempt for practical questions. Never has a revolution in Britain’s position in the world been advocated with such carelessness. The Leave campaign has no plan. And that is not just because there was a shamefully under-explored division between the bulk of Brexit voters who wanted the strong welfare state and solid communities of their youth and the leaders of the campaign who wanted Britain to become an offshore tax haven. Vote Leave did not know how to resolve difficulties with Scotland, Ireland, the refugee camp at Calais, and a thousand other problems, and did not want to know either.

It responded to all who predicted the chaos now engulfing us like an unscrupulous pundit who knows that his living depends on shutting up the experts who gainsay him. For why put the pundit on air, why pay him a penny, if experts can show that everything he says is windy nonsense? The worst journalists, editors and broadcasters know their audiences want entertainment, not expertise. If you doubt me, ask when you last saw panellists on Question Time who knew what they were talking about.

Naturally, Michael Gove, former Times columnist, responded to the thousands of economists who warned he was taking an extraordinary risk with the sneer that will follow him to his grave: “People in this country have had enough of experts.” He’s being saying the same for years.

If sneers won’t work, the worst journalists lie. The Times fired Johnson for lying to its readers. Michael Howard fired Johnson for lying to him. When he’s cornered, Johnson accuses others of his own vices, as unscrupulous journalists always do. Those who question him are the true liars, he blusters, whose testimony cannot be trusted because, as he falsely said of the impeccably honest chairman of the UK Statistics Authority, they are “stooges”.

The Vote Leave campaign followed the tactics of the sleazy columnist to the letter. First, it came out with the big, bold solution: leave. Then it dismissed all who raised well-founded worries with “the country is sick of experts”. Then, like Johnson the journalist, it lied.

I am not going to be over-dainty about mendacity. Politicians, including Remain politicians lie, as do the rest of us. But not since Suez has the nation’s fate been decided by politicians who knowingly made a straight, shameless, incontrovertible lie the first plank of their campaign. Vote Leave assured the electorate it would reclaim a supposed £350m Brussels takes from us each week. They knew it was a lie. Between them, they promised to spend £111bn on the NHS, cuts to VAT and council tax, higher pensions, a better transport system and replacements for the EU subsidies to the arts, science, farmers and deprived regions. When boring experts said that, far from being rich, we would face a £40bn hole in our public finances, Vote Leave knew how to fight back. In Johnsonian fashion, it said that the truth tellers were corrupt liars in Brussels’ pocket.

Now they have won and what Kipling said of the demagogues of his age applies to Michael Gove, Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage.

I could not dig; I dared not rob:

Therefore I lied to please the mob.

Now all my lies are proved untrue

And I must face the men I slew.

What tale shall serve me here among

Mine angry and defrauded young?

The real division in Britain is not between London and the north, Scotland and Wales or the old and young, but between Johnson, Gove and Farage and the voters they defrauded. What tale will serve them now? On Thursday, they won by promising cuts in immigration. On Friday, Johnson and the Eurosceptic ideologue Dan Hannan said that in all probability the number of foreigners coming here won’t fall. On Thursday, they promised the economy would boom. By Friday, the pound was at a 30-year low and Daily Mail readers holidaying abroad were learning not to believe what they read in the papers. On Thursday, they promised £350m extra a week for the NHS. On Friday, it turns out there are “no guarantees”.

If we could only find a halfway competent opposition, the very populist forces they have exploited and misled so grievously would turn on them. The fear in their eyes shows that they know it.

I could not dig; I dared not rob:

Therefore I lied to please the mob.

Now all my lies are proved untrue

And I must face the men I slew.

What tale shall serve me here among

Mine angry and defrauded young?

The real division in Britain is not between London and the north, Scotland and Wales or the old and young, but between Johnson, Gove and Farage and the voters they defrauded. What tale will serve them now? On Thursday, they won by promising cuts in immigration. On Friday, Johnson and the Eurosceptic ideologue Dan Hannan said that in all probability the number of foreigners coming here won’t fall. On Thursday, they promised the economy would boom. By Friday, the pound was at a 30-year low and Daily Mail readers holidaying abroad were learning not to believe what they read in the papers. On Thursday, they promised £350m extra a week for the NHS. On Friday, it turns out there are “no guarantees”.

If we could only find a halfway competent opposition, the very populist forces they have exploited and misled so grievously would turn on them. The fear in their eyes shows that they know it.

Monday, 27 July 2015

The greatest trick Michael Vaughan ever pulled

Rob Smyth in Wisden India

The greatest trick Michael Vaughan ever pulled was convincing England they could beat Australia. As brilliant as England’s 2005 side were, they had no real place beating one of the greatest sides of all time. Yet by convincing them they could win the Ashes, Vaughan kickstarted a series of events that enabled them to do just that. You can see why Steve Harmison called Vaughan “the best liar I’ve ever played with”.

The most important part of England’s win was not Andrew Flintoff’s cartoon superheroism, or Glenn McGrath treading on a cricket ball, or even Gary Pratt. It was one man’s relentless conviction that it was possible to challenge two intimidating opponents: Australia, and the entrenched caution of English cricket. Vaughan did not quite change the DNA of English cricket but, for a few beautiful years, he empowered the most exhilarating England side many of us will ever see. It is why he is the most important English cricketer since Sir Ian Botham.

England’s symbolic victories in the Champions Trophy semi-final of 2004 and the one-off T20 international at the start of the 2005 summer were very important, but the most significant backstory to the 2005 Ashes is the evolution of Vaughan from underachieving, defensively-minded county batsman to the world’s best attacking batsman, which in turn enabled him to become, as England captain, a kind of arrogant visionary who waged war on the received wisdom surrounding Australia.

A key moment in that development was Vaughan’s breezy 33 at Brisbane in 2002, the magical little acorn from which England’s 2005 Ashes win grew. Vaughan’s swaggering cameo in his first Ashes innings confirmed the view he had formed in the previous six months – that Australia, and particularly Glenn McGrath, not only could be attacked but had to be attacked. That attitude informed everything he did for the remainder of his Ashes mirabilis in 2002–03 and, even more importantly, what he did once he became Test captain the following summer.

England had a number of unlikely heroes who helped them win the Ashes in 2005, from Pratt to Ricky Ponting. We should probably add Darren Lehmann and Sachin Tendulkar to the list; maybe even give them MBEs. Lehmann started playing for Yorkshire in 1997 and began to broaden Vaughan’s mind. When Vaughan came into the Yorkshire dressing-room in the early 1990s, he says he found a culture in which you were slaughtered for “batting like a millionaire” if you got out playing an attacking shot. He thus grew up as a classical, defensive batsman who batted time. It was all he knew.

Lehmann was only four years older than Vaughan, yet in many ways he was his mentor: worldly, streetwise, ceaselessly positive and with the sharpest cricket brain. “Darren Lehmann really taught me how to play the game properly,” said Vaughan. “He gave me so much advice and made me into the player that I ended up being – and made me into a thoughtful, aggressive captain.”

When Vaughan returned from a promising first tour as an England player – to South Africa in 1999–2000 – Lehmann suggested he was hiding his light under a bushel. He encouraged Vaughan to play more shots and especially to always be on the look-out for quick singles – not to bat time, but to bat runs. “I loved Boof,” wrote Vaughan in Time to Declare. “He was everything an overseas player ought to be and a huge influence on me.”

That influence continued when Vaughan became England captain. He had two men “outside the England bubble”, as he put it, to whom he turned for advice on a regular basis: Lehmann and an unnamed businessman who “never played top-level cricket but always challenged me and came from a different angle”. Vaughan was always keen to pick as many brains as possible; crucially, he was extremely decisive at sifting through observations and advice from others.

He almost always listened to Lehmann’s counsel, never more importantly than when Lehmann told him to bring a one-day mindset to his batting in four- and five-day cricket. It was such a fundamental change in Vaughan’s batting philosophy that it took him a couple of years to fully retrain his brain. But his strike rate in his first four years of Test cricket, from 1999–2002, told a clear story: 27 runs per 100 balls in 1999, then 41, 42 and 64.

A series of annoying injuries – calf, finger, hand and knee – as well as Duncan Fletcher’s desire to give Graeme Hick a chance and the need to play five bowlers in India meant that Vaughan, despite a promising start to his England career, played only three out of 14 Tests between November 2000 and December 2001. At the age of 27, he could not afford much more lost time. Graham Thorpe’s personal problems allowed him back in the side in India, and then Vaughan was pushed up to open for the first time in the 1–1 draw against New Zealand in 2001–02. It did not start well; on some dicey pitches he made 131 runs in six innings. But he demonstrated his new approach. In the first Test, England were 2 for 2 when Vaughan hooked his second ball of the series for six. The death of Ben Hollioake during the second Test was “a decisive moment in my life” and made him even more determined to remember that cricket was sport and should be enjoyed.

At the start of the 2002 English summer Vaughan averaged 31.15 from 16 Tests. Before the first Test against Sri Lanka he sensed something wasn’t right against left-arm seam – of which he would be facing plenty that summer – and asked Duncan Fletcher to have a look in the nets. After four balls, Fletcher spotted that Vaughan was too open, with his shoulders and body facing towards midwicket rather than between mid-on and the bowler. “The subtle change paid instant dividends… defence and attack all clicked.” He made a century in the first Test of the summer against Sri Lanka, and then three more against India. In New Zealand his problem was getting out in the 20s and 30s; against India it was getting out in the 190s. It was life-changing stuff. Vaughan ran with the mood of that summer and kept on running until England had won the Ashes three years later.

As the summer developed, with the following winter’s Ashes in mind, Vaughan became sufficiently emboldened that he decided to attack Australia. “I was not intending to be totally gung-ho, slash and bash, but to be nothing other than positive.” It was his eureka moment.

When Vaughan returned from a promising first tour as an England player – to South Africa in 1999–2000 – Lehmann suggested he was hiding his light under a bushel. He encouraged Vaughan to play more shots and especially to always be on the look-out for quick singles – not to bat time, but to bat runs. “I loved Boof,” wrote Vaughan in Time to Declare. “He was everything an overseas player ought to be and a huge influence on me.”

If you mention Vaughan, Tendulkar and 2002 then people will think of the wonder ball with which Vaughan bowled Tendulkar at Trent Bridge. Far more important, in the long term, was the postscript to that delivery. At the end of the series, Vaughan asked Tendulkar to sign the ball and stump from that wicket. Tendulkar asked him to sit down and chat cricket, which they did for half an hour. The conversation inevitably moved on to Australia. Tendulkar told Vaughan of the Adelaide Test of 1999–2000, in which he and Dravid allowed McGrath to bowl a spell of 8-7-1-0. After that, Tendulkar decided he would never again show McGrath and Australia too much respect. “That confirmed to me what I had already been thinking about the winter to come: that I would not be holding back in taking them on,” said Vaughan. “It turned out to be one of my better resolutions in life.”

Every time Vaughan said he was going to attack McGrath, teammates looked at him as if he had said he was going to break into the Bank of England. He has having a coffee in Chelsea with his captain Nasser Hussain, who asked him what he planned to do against McGrath. “I won’t die wondering,” said Vaughan. “Oh, right,” said Hussain.

Vaughan remembers other players saying: “No chance; he just won’t give you anything to hit.” It irritated him to the point where bloody-mindedness started to kick in. “There was too much of the wrong mentality about,” he said. “The defeatism was plain to me.”

Even allowing for Vaughan’s great form in 2002, it was quite a conceit. He had never played an Ashes Test but he was going to take on McGrath, the king of individual contests, and Australia in their own manor, and in their own manner. Who the hell did he think he was?

Vaughan even went so far as to say in the press that he hoped McGrath would target him. Before he started predicting that every Ashes series would end 5–0, McGrath made a point of publicly announcing his target in the opposition team. It was pretty much a death sentence. McGrath called it “mind over batter”. He would identify his targets in an unnerving, matter-of-fact manner, with a couple of pertinent, indisputable facts and just a smidgen of smartarsery to get under his opponent’s skin. It was textbook mental disintegration.

In this case McGrath played on Vaughan’s abysmal record against Australia. He got a golden duck in his only innings against Australia, when he was bowled by Jason Gillespie in an ODI in 2001; he was also dismissed by the only delivery he had ever faced from McGrath, this time in a county match. “He’s obviously their form player if you look at the last season,” McGrath said. “I have had quite a lot of success in the past against guys I want to target. He hasn’t really got the form on the board against Australia, so we’ll see how he goes.”

Vaughan admitted that the reactions of other players to his intention of attacking Glenn McGrath irritated him to the point where bloody-mindedness started to kick in as the defeatism was plain to him. © Getty Images

Vaughan took it as a compliment. “I just thought, ‘this is a bit of all right, not bad at all. I’ve been picked out by the best in the world’… McGrath called me a grinder who could bat for long periods but who could be suspect to the short ball. It was my intention to alter this thinking.”

If you go at the king, you best not miss. “This will sound arrogant but I really quite fancied facing McGrath,” said Vaughan. “If the ball was seaming he was a bit of a nightmare, but if it was swinging I found him quite juicy.” Arrogance, like bacteria, is instinctively perceived as a bad thing but also comes in a good form. Throughout Vaughan’s career, that arrogance – and even entitlement – facilitated so much of what he and England achieved.

Before the 2002–03 tour, Vaughan didn’t so much cope with fear of failure as ignore it. He changed his mind about watching videos of the Australian bowlers as preparation because he was worried if he did that he would start playing the bowler, not the ball. His tour did not start well, however. He missed the first three matches because his knee took longer to heal than expected, though he struck 127 against Queensland in his only innings before the first Test at Brisbane. On the first day of the series he had a nightmare in the field; he let the second ball of the day through his legs, the usual depressing tone-setter, and later dropped a dolly at extra cover.

England eventually came to bat on the second afternoon after Australia posted 492. There was a hush of anticipation. “We were very interested in seeing Vaughan,” said Adam Gilchrist in Walking to Victory. “We’d heard a lot about him. He was the big name that Glenn McGrath had decided to target this summer.”

There were umpteen reasons for Vaughan to ease his way carefully into the series. He’d had a terrible time in the field. His knee was sore. There were only nine overs to tea. His fledgling record against both McGrath and Australia was awful. He averaged 27.94 in overseas Tests. Vaughan didn’t get a toss about any of it. That was then and this was now.

In many respects Vaughan was winging it. He was 28, but had only been opening for England for seven months. Yet he had the unshakeable conviction of a man who had recently had an epiphany. His state of mind was perfect. So was his state of gut; Vaughan has always been an advocate of gut instinct, and his kept telling him that, on an individual level, he could conquer Australia. His mind was fresh and uncluttered: “Keep things simple – eye on the ball, hit and look to run.”

Vaughan knew that first impressions are important in sport, which has a habit of perpetuating itself. One look at Shane Warne would have reminded him of that. Steve Waugh greeted him with six men in the cordon as well as the wicket-keeper Gilchrist. Vaughan saw the consequent gaps in front of the wicket, not the men behind him. He faced only a single ball in McGrath’s first two overs, which he pushed through mid-on for a single. During that time McGrath got into his usual groove and had Marcus Trescothick dropped in the slips. Vaughan then faced every ball of McGrath’s third over – and hammered it for 12. The second ball, fractionally short of a length, was pulled impatiently through midwicket for four. As Vaughan ran past, McGrath used the side of his mouth to scold him for his impertinence. The fifth ball was driven gorgeously through the covers for four.

He took nine more from McGrath’s next over, including a savage back cut for four, an extravagant, mis-hit pull into the open spaces for two and a back-foot drive for three. This time McGrath said nothing, just licked his lips. Even Vaughan’s leaves were aggressive, a last-minute decision to abort an attacking shot. It was the sporting equivalent of the head-turning arrival; he had the instant respect of the Australian commentators on Channel 9, who were fascinated to see somebody attack McGrath, and also the Australians on the field. “I sensed immediately that we were up against quality,” said Gilchrist. “There was something about Vaughan’s balance and composure.”

More than anything else, England won the Ashes because Michael Vaughan kept asking why. Why couldn’t Glenn McGrath be attacked? Why could Australia not mentally disintegrate like all other humans? Why couldn’t England win the Ashes with an inexperienced team? Whenever he was questioned, or had slight doubts himself, he kept returning to one simple point: that the alternative hadn’t worked for 16 years.

McGrath was taken out of the attack after that, with figures of 4-1-23-0. Vaughan said he got carried away with his attacking mood and was even more aggressive than he intended. He was playing the bowler not the ball – but in a good way. He slammed another exhilarating boundary off Andy Bichel, clouting a short ball over cover. McGrath returned to the attack after tea and got his man with a fine delivery that jagged back off the seam to take the inside edge as Vaughan shaped to pull. Vaughan had made 33 from 36 balls, within which he scored 25 off just 19 from McGrath – an unimaginable strike rate of 132. “A lot of people called it a ballsy effort to get after them,” said Vaughan. “I just called it positive.”

That, more than his eventual dismissal, was what Vaughan took from the innings – especially when Warne congratulated him after play for being the first Englishman he had seen go after McGrath. Such positive reinforcement was vital, and kept coming throughout the series. We didn’t realise at the time, but it was all crescendoing towards Vaughan creating a culture that would allow England to win the Ashes.

Vaughan got a golden duck in the second innings, with McGrath dismissing him again, but it was a poor LBW decision and he was able to rationalise it as irrelevant. “I am sure he thought he had a psychological edge on me, but he was mistaken,” said Vaughan in A Year In The Sun. “I looked at the positives. I had played well in the first innings and been unfortunate in the second.” Two weeks later Vaughan hammered 177 on the first day of the second Test at Adelaide; this time he attacked McGrath judiciously, with 50 from 87 balls. He should have been given out on 19, but the third umpire gave him the benefit of what doubt there was when Justin Langer claimed a low catch at cover. Had he failed then, maybe he would have started to have doubts or rethink his approach. Steve Davis, the third umpire, is another man who unwittingly helped England win the Ashes in 2005.

“That innings had a real impact on me,” said Gilchrist of Vaughan’s 177. “I remember thinking: ‘This is a class act.’” At the close of play, Gillespie came into the England dressing-room specifically to congratulate Vaughan. Yet more positive reinforcement. He had confirmed the promising impression of the first Test and achieved one of the most worthwhile things in cricket: the respect of the Australians. He had steel and skill or, in the parlance of our time, ticker and tekkers. This was not just another Pom to the slaughter.

When Vaughan became the captain, he transmitted the same attitude of standing up to the Australians, without which England would have had zero percent of winning the Ashes in 2005. © AFP

Steve Waugh later said Vaughan was “the only guy I’ve ever seen succeed after Glenn McGrath made his annual declaration of intent upon the opposition’s key batsman”. Vaughan went on to make three huge centuries in the series, and ended it as the world’s No.1 batsman in the ICC rankings. Seven months earlier he had been 44th, behind, among others, Habibul Bashar and Mathew Sinclair. “He batted like the best player who had ever lived,” said his opening partner Trescothick. “I remember thinking they could not bowl at him, and the ‘they’ were bloody Glenn McGrath and Shane Warne.” He ended with 633 runs in five Tests; the manner of the first 33, in that first innings at Brisbane, made the other 600 possible.

“I can’t remember an opener playing McGrath, Lee and Gillespie the way Vaughan did that summer,” said Lehmann. “At times he was treating them with contempt… dare I say it, he was batting like an Aussie.” Vaughan’s geographical identity is different to most: he is a Lancashire-born Yorkshireman and an Englishman with the attitude of an Aussie. There was an infectious swagger about Vaughan which, along with the sheer beauty of his batting and the runs he scored in industrial quantities, gave England fans considerable pride despite the side suffering another 4-1 Ashes defeat. We had no idea that his performance would also inform the ultimate high in the next series.

“There was a huge amount on that trip that got stored away at the back of my mind for the purposes of tackling Australia in the future,” he said. “The basic lesson was that, if you were going to stand up to the Australians, you could not have anyone in the team who had this fear about them.”

When he later became captain, Vaughan transmitted that attitude to his team; without it, they would have had approximately 0.00 per cent chance of winning in 2005. “It’s amazing how once one player excels, his teammates find the leap from good to excellent to be not so difficult,” said Steve Waugh. “It suddenly becomes real rather than a dream.” It also made Vaughan one of the world’s leading authorities on how to play against Australia, which made the players listen to his every word.

More than anything else, England won the Ashes because Michael Vaughan kept asking why. Why couldn’t Glenn McGrath be attacked? Why could Australia not mentally disintegrate like all other humans? Why couldn’t England win the Ashes with an inexperienced team? Whenever he was questioned, or had slight doubts himself, he kept returning to one simple point: that the alternative hadn’t worked for 16 years.

Vaughan’s overall record against McGrath was not actually that good. Whose record was? In the 2002–03 series he scored 142 runs and was dismissed four times, a head-to-head average of 35.50; overall, including the 2005 Ashes, he made 205 and was dismissed six times. But in that first innings, he showed – to Australia, to himself and to all of England – that McGrath could be taken on. He had made his symbolic statement. There was a similar example during the 1997 Ashes: after his career-saving century at Edgbaston, Mark Taylor made four runs in the next four innings. But hardly anybody noticed, and those who did notice did not care. Taylor’s form was no longer an issue. So much of sport is about bluff, perception and symbolism, and Vaughan understood that better than most.

When he later became captain, Vaughan transmitted that attitude to his team; without it, they would have had approximately 0.00 per cent chance of winning in 2005. “It’s amazing how once one player excels, his teammates find the leap from good to excellent to be not so difficult,” said Steve Waugh. “It suddenly becomes real rather than a dream.” It also made Vaughan one of the world’s leading authorities on how to play against Australia, which made the players listen to his every word.

Vaughan’s approach in that 33 was a longer-term version of a tactic Steve Waugh employed in so many individual innings: take calculated risks to get to 20 or 30 as soon as possible so that you reverse the momentum and spread the field, and then you can settle in for the long haul. After taking on McGrath, he could then focus on easier targets (these things are relative) like Stuart MacGill and, in 2005, a flagging Gillespie.

Life is a complex, sprawling flow chart, in which apparently minor incidents usher us in a completely different direction, and it is fascinating – and a little terrifying – to reflect on all the little things that made Vaughan into the world’s best batsman, without which he probably would not have become an Ashes-winning captain: Lehmann joining Yorkshire, Thorpe’s personal problems, Hollioake’s death, Fletcher spotting that technical flaw, the ball to Tendulkar – and those injuries in 2001, which were so frustrating at the time but, with hindsight, were surely a blessing. Although Vaughan had started to modify his game, he was probably not quite ready to go after McGrath and the Australians that summer; a difficult series might have left him with mental scars like the other England players.

Even the timing of Vaughan’s ascent was perfect. Hussain, a man who was at his most comfortable with the feel of the wall against his back, was perfectly suited to dragging England out of the doldrums. Vaughan probably could not have done that, but between them, over a six-year period, they turned the worst team into a team who could outplay the best team in the world.

As Vaughan’s team developed in 2003 and 2004, everything he did was geared towards beating Australia. He became obsessed with mental scarring, and that Australia could only be beaten with aggression and fresh minds. It was reinforced when Lehmann, unprompted, made the same observation. When the 2005 Ashes started, England had five players making their debuts against Australia. Overall the team had made 25 Ashes appearances between them, fewer than Shane Warne on his own. In total Australia had 129.

“I wasn’t 100 per cent sure we were ready for them, wondering if perhaps they were coming a year too soon.” Not that he told anyone. He was far too good a liar for that.

Sunday, 4 May 2014

He's now in prison, but Max Clifford's macho culture lives on

Max Clifford may be in prison, but the culture he sold and espoused lives on

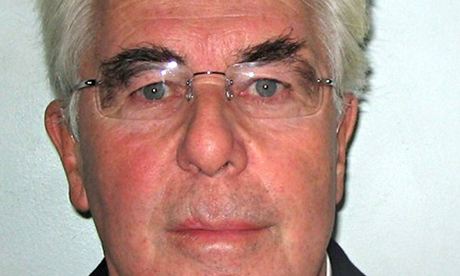

A police photograph of disgraced PR guru Max Clifford. Photograph: /PA

In 2005, I found out, quite by chance, that Max Clifford was having an affair with a married woman. I say, "quite by chance", but it was only chance on my side. It was entirely intentional on his. He had arranged a press trip to Galway – a typical Clifford hybrid affair, an opportunity to promote a number of his clients, Club 328, a private jet charter club, the boy band singer Brian McFadden and, most importantly, Clifford himself – and he'd invited along a journalist.

If you want to know how Clifford controlled the media, or the kind of power and influence he wielded for decades, consider this. Two minutes into the trip, he sidled up to me and explained the presence of the attractive 40-ish-year-old woman at his side: "By the way, Carole," he said. "For the purposes of this article, Jo is my PA."

A year later, I interviewed him and revealed in an article the story of the affair: "The girls from his office got drunk and told me what every tabloid diarist writer and showbiz reporter in the country apparently knew. And, for an ugly lesson in how the media works, here it is: none of them wrote about it because none of them could afford to offend one of the prime sources of quality scandal."

This was 2005, when Rebekah Brooks was the editor of the Sun. And Andy Coulson was the editor of the News of the World. They did not print a story about Clifford, of course. Nor did Piers Morgan at the Daily Mirror. The choice I was left with, I wrote, was "an unappetising dilemma: collude with Clifford and the entire tabloid press establishment or potentially wreck someone else's marriage".

It's nearly a decade ago, but I've thought about Clifford relatively often since then. I thought about him when Rebekah Brooks and Andy Coulson were arrested. When various witnesses stood in the box and talked about the ways he had tried to impress and manipulate him.

When the issue of the size of Clifford's penis became a matter for the jury, I went back to the story I wrote in 2006 to check what he'd told me on the subject. Clifford is "impervious to criticism", I wrote. He doesn't even attempt to justify himself "because I know I can't". The only thing he'd really mind, he tells me is if someone said he was rubbish in bed. Or "that I had a small willy".

It's a measure of the desperateness of his situation that Clifford allowed his penis, his "willy" as he'd have it, which his doctor claimed was "within the average range for a Caucasian male of Mr Clifford's age", to be one of the main lines of defence. This was a man well and truly on the ropes. But then, Clifford had proved that he would say anything to anybody at any time. He was a hopeless witness for his own defence: a self-confessed, bare-faced liar.

During the trial, witnesses talked about Clifford's office as his sexual fiefdom, but it was the press that was his real fiefdom. It was the expectation of control. Of obedience. But this wasn't solely down to him. He was part of a wider media landscape that regarded human nature as base, people as corruptible, public figures as grist to the scandal mill.

A media landscape that has bequeathed to us: the idea that public life is a testing ground for whoever has the most testosterone; that everybody is out for whatever they can get; that distrust and betrayal and contempt are everyday aspects of the human condition.

"Nearly everybody I've ever known has affairs," Clifford told me. "Nearly every journalist I've ever met has affairs. I haven't met one, in 40-odd years, who hasn't. It's not that I think they are, I know they are!"

Well, no, Max, you don't, actually. At the time, I wrote about how depressing it was to be in his moral universe: "A world where men are men and women are trollops." But this was what he truly believed. And for years, this was the bedrock of the culture that permeated our press, our world, our lives.

I remember one year, during these times, when the News of the World won newspaper of the year at the Press Awards. I was at the awards at the Observer table, sitting next to an American journalist, Sarah Lyall, who was writing for the online magazine, Slate. The evening, she wrote, was "like a soccer match attended by a club of misanthropic inebriates"; the tone set by Sir Bob Geldof, there to present a prize to the Sun. "I've just been down at the bog," he said. "And it's true that rock stars do have bigger knobs than journalists."

Knobs, willies, cocks. There's been a turbocharged masculinity at the heart of British newspaper culture for decades. At the heart of public life. Max Clifford has gone, undone by his need to assert himself, to dominate, to brag, to boast of his affairs, his power, his influence.

And, so it turns out, to abuse the trust not just of the British public, but of vulnerable underage girls too. It all seems so much of a piece.

Some things have certainly changed. Clifford is in jail. Leveson has come and gone. But this competition, the pissing competition that is British public life, the need to prove the size of your cock, the expectation that public figures are corruptible, contemptible, that all people, everywhere, are simply out for themselves, this idea that life is, at its core, a willy-waving contest, this has not gone. This is still here.

This is Max Clifford's world and we live in it still.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)