Max Clifford may be in prison, but the culture he sold and espoused lives on

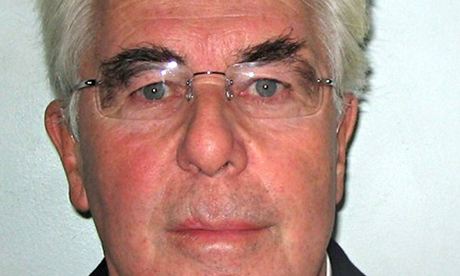

A police photograph of disgraced PR guru Max Clifford. Photograph: /PA

In 2005, I found out, quite by chance, that Max Clifford was having an affair with a married woman. I say, "quite by chance", but it was only chance on my side. It was entirely intentional on his. He had arranged a press trip to Galway – a typical Clifford hybrid affair, an opportunity to promote a number of his clients, Club 328, a private jet charter club, the boy band singer Brian McFadden and, most importantly, Clifford himself – and he'd invited along a journalist.

If you want to know how Clifford controlled the media, or the kind of power and influence he wielded for decades, consider this. Two minutes into the trip, he sidled up to me and explained the presence of the attractive 40-ish-year-old woman at his side: "By the way, Carole," he said. "For the purposes of this article, Jo is my PA."

A year later, I interviewed him and revealed in an article the story of the affair: "The girls from his office got drunk and told me what every tabloid diarist writer and showbiz reporter in the country apparently knew. And, for an ugly lesson in how the media works, here it is: none of them wrote about it because none of them could afford to offend one of the prime sources of quality scandal."

This was 2005, when Rebekah Brooks was the editor of the Sun. And Andy Coulson was the editor of the News of the World. They did not print a story about Clifford, of course. Nor did Piers Morgan at the Daily Mirror. The choice I was left with, I wrote, was "an unappetising dilemma: collude with Clifford and the entire tabloid press establishment or potentially wreck someone else's marriage".

It's nearly a decade ago, but I've thought about Clifford relatively often since then. I thought about him when Rebekah Brooks and Andy Coulson were arrested. When various witnesses stood in the box and talked about the ways he had tried to impress and manipulate him.

When the issue of the size of Clifford's penis became a matter for the jury, I went back to the story I wrote in 2006 to check what he'd told me on the subject. Clifford is "impervious to criticism", I wrote. He doesn't even attempt to justify himself "because I know I can't". The only thing he'd really mind, he tells me is if someone said he was rubbish in bed. Or "that I had a small willy".

It's a measure of the desperateness of his situation that Clifford allowed his penis, his "willy" as he'd have it, which his doctor claimed was "within the average range for a Caucasian male of Mr Clifford's age", to be one of the main lines of defence. This was a man well and truly on the ropes. But then, Clifford had proved that he would say anything to anybody at any time. He was a hopeless witness for his own defence: a self-confessed, bare-faced liar.

During the trial, witnesses talked about Clifford's office as his sexual fiefdom, but it was the press that was his real fiefdom. It was the expectation of control. Of obedience. But this wasn't solely down to him. He was part of a wider media landscape that regarded human nature as base, people as corruptible, public figures as grist to the scandal mill.

A media landscape that has bequeathed to us: the idea that public life is a testing ground for whoever has the most testosterone; that everybody is out for whatever they can get; that distrust and betrayal and contempt are everyday aspects of the human condition.

"Nearly everybody I've ever known has affairs," Clifford told me. "Nearly every journalist I've ever met has affairs. I haven't met one, in 40-odd years, who hasn't. It's not that I think they are, I know they are!"

Well, no, Max, you don't, actually. At the time, I wrote about how depressing it was to be in his moral universe: "A world where men are men and women are trollops." But this was what he truly believed. And for years, this was the bedrock of the culture that permeated our press, our world, our lives.

I remember one year, during these times, when the News of the World won newspaper of the year at the Press Awards. I was at the awards at the Observer table, sitting next to an American journalist, Sarah Lyall, who was writing for the online magazine, Slate. The evening, she wrote, was "like a soccer match attended by a club of misanthropic inebriates"; the tone set by Sir Bob Geldof, there to present a prize to the Sun. "I've just been down at the bog," he said. "And it's true that rock stars do have bigger knobs than journalists."

Knobs, willies, cocks. There's been a turbocharged masculinity at the heart of British newspaper culture for decades. At the heart of public life. Max Clifford has gone, undone by his need to assert himself, to dominate, to brag, to boast of his affairs, his power, his influence.

And, so it turns out, to abuse the trust not just of the British public, but of vulnerable underage girls too. It all seems so much of a piece.

Some things have certainly changed. Clifford is in jail. Leveson has come and gone. But this competition, the pissing competition that is British public life, the need to prove the size of your cock, the expectation that public figures are corruptible, contemptible, that all people, everywhere, are simply out for themselves, this idea that life is, at its core, a willy-waving contest, this has not gone. This is still here.

This is Max Clifford's world and we live in it still.

No comments:

Post a Comment