'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label ISIS. Show all posts

Showing posts with label ISIS. Show all posts

Monday, 26 October 2015

Wednesday, 29 July 2015

The West likes to think that 'civilisation' will defeat Isis, but history suggests otherwise

Robert Fisk in The Independent

Hitler set a bad example. He was evil. His regime was evil. His Reich was destroyed, the Nazis vanquished, the Fuhrer dying by his own hand in the ashes of the European nightmare. Bad guys lose. Good guys win. Morality, human rights, law, democracy – though with the latter, we should perhaps speak carefully – will always prevail over wickedness. That’s what the Second World War taught us.

We have grown up in a Western society that believes in such simple, dodgy, history lessons. The world’s major religions teach us about goodness, humility, family, love, faith. So why should we not – however liberal, agnostic, cynical – cling on to our fundamental belief that violence and torture and cruelty will never outlast the power and courage of the righteous?

Isis is evil. It massacres its opponents, slaughters civilians, beheads the innocent, rapes children and enslaves women. It is “apocalyptic”, according to the Americans, and therefore it is doomed. Better still, Ash Carter – the US Secretary of Defence who accused the Iraqis of running away from Isis – lectured the Iraqi Prime Minister last week. His message – I could hardly believe this naivety – was Hollywood-clear. “Civilisation always wins over barbarism.”

But does it? We only have to go back to the lie about the Second World War in my first sentence. Sure, Hitler lost. But our ally Stalin won. The 1917 Russian Revolution gave rise to one of the Gorgons of our age: Soviet dictatorship, the mass starvation leading the to death of millions, barbarism – on an Ash Carter scale – and evil incarnate ruled in Russia and Eastern Europe for more than 70 years, 40 of them after the Second World War.

The Romans kept “barbarism” at bay for almost a thousand years, but in the end the Goths, Ostrogoths and Visigoths – the Isis of their time – won. Unless you were opposed to Rome, in which case Roman barbarism – crucifixion, slavery, torture, massacre (the whole Isis gamut minus the videotapes) – was victorious for almost a thousand years.

Attila the Hun, the Scourge of God, destroyed almost everything between Persia and the Mediterranean. Ghengis Khan, an inevitable actor in this sordid drama, kept going until his death in 1227 – 30 years longer than Isis has so far ruled. His grandson Hulagu was invoked by General Angus Maude when he “liberated” Baghdad in 1917 and brought “civilisation” to Mesopotamia. Ash Carter should read Maude’s proclamation to the people of Baghdad: “Since the days of Hulagu, your citizens have been subject to the tyranny of strangers, your palaces have fallen into ruins, your gardens have sunken in desolation and your forefathers and yourselves have groaned in bondage.” Pretty much like Isis, in other words. But, by Maude’s count, this “tyranny” lasted for around 700 years.

Now let’s go forward to the years immediately after we brought “civilisation” – again – to Baghdad, by illegally invading Iraq in 2003. Between daily trips to the city mortuary and visits to tents of mourning, angry families would tell us that the “freedom” we brought had given them anarchy. They hated the dictator Saddam who slaughtered his opponents – and who imposed 24 years of “barbarism” on his people – but at least he gave them security. If you have children, these people would tell us, you want them to come home from school. You do not want them to be murdered. So which do we prefer, they asked us? Freedom or security? Democracy or Saddam?

Fearful of the Shia-dominated Iraqi government, whose militias slaughtered them, and the corrupt Arab dictatorships, who suppressed them, many hundreds of thousands of Sunni Muslims appear to have found security under Isis. Not the Shias, nor the Christians, nor the Yazidis. There is no “freedom”, as we would call it. But Sunni Iraqi men in Beirut, for example, regularly travel to and from the Isis Syrian capital Raqqa and report that – provided they don’t smoke or drink alcohol, their women are covered, and they do not oppose Isis – they are left alone: to do business, to visit families, to travel in safety. (Much the same applied under the Taliban in Afghanistan.)

ID cards are issued in Isis-land, the river police have newly-painted boats, taxes are raised, and yes, punishment is barbarous. But that does not mean the “Islamic Caliphate” is going to be conquered by “civilisation”.

And how can we believe that it will, when our own public-relations boss raves on about “British values” – and at the same time worships the venal, hypocritical, immensely wealthy and dangerous men who have helped to inspire Isis. I refer, of course, to those Saudis whose crazed Sunni Wahhabist cult has encouraged Isis, whose grotesque puritanism has led them to adopt a head-chopping extremism, which lies at the heart of Isis’s own “barbarism”. Sure, the Saudi state arrests Isis cells. But these same Saudis are now killing thousands of Shia Houthis in Yemen in a bombing campaign supported by our Western nations. And what does David Cameron do when the desiccated old king of this weird state dies? Money talks louder than “civilisation”. So he orders that British flags should be flown at half-mast. Now that’s what I call British values!

Poor old Dave. He loathes Isis but adores one of its elderly “facilitators”. Yet fear not. “Civilisation” may yet win over “barbarism”. My own suspicion is that Ash, Dave and the rest will try to buy up Isis, split them into factions and choose the “moderates” among them. Then we’ll have a new, liberal Isis – people we can do business with, the sort of chaps we can get along with, sins forgotten – and we can then establish relations with them as cosy as those the Americans maintained with Hitler’s murderous rocket scientists after “civilisation” conquered “barbarism” in the Second World War.

So much for “civilisation”.

Hitler set a bad example. He was evil. His regime was evil. His Reich was destroyed, the Nazis vanquished, the Fuhrer dying by his own hand in the ashes of the European nightmare. Bad guys lose. Good guys win. Morality, human rights, law, democracy – though with the latter, we should perhaps speak carefully – will always prevail over wickedness. That’s what the Second World War taught us.

We have grown up in a Western society that believes in such simple, dodgy, history lessons. The world’s major religions teach us about goodness, humility, family, love, faith. So why should we not – however liberal, agnostic, cynical – cling on to our fundamental belief that violence and torture and cruelty will never outlast the power and courage of the righteous?

Isis is evil. It massacres its opponents, slaughters civilians, beheads the innocent, rapes children and enslaves women. It is “apocalyptic”, according to the Americans, and therefore it is doomed. Better still, Ash Carter – the US Secretary of Defence who accused the Iraqis of running away from Isis – lectured the Iraqi Prime Minister last week. His message – I could hardly believe this naivety – was Hollywood-clear. “Civilisation always wins over barbarism.”

But does it? We only have to go back to the lie about the Second World War in my first sentence. Sure, Hitler lost. But our ally Stalin won. The 1917 Russian Revolution gave rise to one of the Gorgons of our age: Soviet dictatorship, the mass starvation leading the to death of millions, barbarism – on an Ash Carter scale – and evil incarnate ruled in Russia and Eastern Europe for more than 70 years, 40 of them after the Second World War.

The Romans kept “barbarism” at bay for almost a thousand years, but in the end the Goths, Ostrogoths and Visigoths – the Isis of their time – won. Unless you were opposed to Rome, in which case Roman barbarism – crucifixion, slavery, torture, massacre (the whole Isis gamut minus the videotapes) – was victorious for almost a thousand years.

Attila the Hun, the Scourge of God, destroyed almost everything between Persia and the Mediterranean. Ghengis Khan, an inevitable actor in this sordid drama, kept going until his death in 1227 – 30 years longer than Isis has so far ruled. His grandson Hulagu was invoked by General Angus Maude when he “liberated” Baghdad in 1917 and brought “civilisation” to Mesopotamia. Ash Carter should read Maude’s proclamation to the people of Baghdad: “Since the days of Hulagu, your citizens have been subject to the tyranny of strangers, your palaces have fallen into ruins, your gardens have sunken in desolation and your forefathers and yourselves have groaned in bondage.” Pretty much like Isis, in other words. But, by Maude’s count, this “tyranny” lasted for around 700 years.

Now let’s go forward to the years immediately after we brought “civilisation” – again – to Baghdad, by illegally invading Iraq in 2003. Between daily trips to the city mortuary and visits to tents of mourning, angry families would tell us that the “freedom” we brought had given them anarchy. They hated the dictator Saddam who slaughtered his opponents – and who imposed 24 years of “barbarism” on his people – but at least he gave them security. If you have children, these people would tell us, you want them to come home from school. You do not want them to be murdered. So which do we prefer, they asked us? Freedom or security? Democracy or Saddam?

Fearful of the Shia-dominated Iraqi government, whose militias slaughtered them, and the corrupt Arab dictatorships, who suppressed them, many hundreds of thousands of Sunni Muslims appear to have found security under Isis. Not the Shias, nor the Christians, nor the Yazidis. There is no “freedom”, as we would call it. But Sunni Iraqi men in Beirut, for example, regularly travel to and from the Isis Syrian capital Raqqa and report that – provided they don’t smoke or drink alcohol, their women are covered, and they do not oppose Isis – they are left alone: to do business, to visit families, to travel in safety. (Much the same applied under the Taliban in Afghanistan.)

ID cards are issued in Isis-land, the river police have newly-painted boats, taxes are raised, and yes, punishment is barbarous. But that does not mean the “Islamic Caliphate” is going to be conquered by “civilisation”.

And how can we believe that it will, when our own public-relations boss raves on about “British values” – and at the same time worships the venal, hypocritical, immensely wealthy and dangerous men who have helped to inspire Isis. I refer, of course, to those Saudis whose crazed Sunni Wahhabist cult has encouraged Isis, whose grotesque puritanism has led them to adopt a head-chopping extremism, which lies at the heart of Isis’s own “barbarism”. Sure, the Saudi state arrests Isis cells. But these same Saudis are now killing thousands of Shia Houthis in Yemen in a bombing campaign supported by our Western nations. And what does David Cameron do when the desiccated old king of this weird state dies? Money talks louder than “civilisation”. So he orders that British flags should be flown at half-mast. Now that’s what I call British values!

Poor old Dave. He loathes Isis but adores one of its elderly “facilitators”. Yet fear not. “Civilisation” may yet win over “barbarism”. My own suspicion is that Ash, Dave and the rest will try to buy up Isis, split them into factions and choose the “moderates” among them. Then we’ll have a new, liberal Isis – people we can do business with, the sort of chaps we can get along with, sins forgotten – and we can then establish relations with them as cosy as those the Americans maintained with Hitler’s murderous rocket scientists after “civilisation” conquered “barbarism” in the Second World War.

So much for “civilisation”.

Tuesday, 28 July 2015

Greek debt crisis: A tale of ritual humiliation

Mark Steel in The Independent

What a relief that the Greeks have finally seen sense, and agreed to Angela Merkel’s demand that their Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras must scrub Berlin with a dishcloth, and crawl along the banks of the Rhine in a thong barking like a dog.

The week before he’d agreed to dress as a fairy and sing “The Good Ship Lollipop” while German children poked him with stinging nettles, but now that isn’t enough. So he has to accept even more measures essential to stabilising the Greek economy, such as being hosed down with kebab fat while naming the German squad that won the 1954 World Cup.

Otherwise, as EU leaders made clear, there would be no way Greece could stay inside the solar system; they’d have to orbit a different star in a faraway galaxy, which could be extremely damaging to the Greek tourist industry.

Instead of inviting further chaos by leaving Greece in the hands of the Greeks, their finances have been handed over entirely to the only people we can trust to behave responsibly at all times: the banks. Thank the Lord we’ve got at least one institution that has never behaved irresponsibly or recklessly in any way.

Perhaps the Greeks should have gone to Brussels and said they were rebranding Greece, so it’s no longer a country, but a bank. They’d have been bailed out by lunch and given a free set of steak knives as an extra gift. Instead they’ve got to sell off their entire country. By Christmas you’ll be able to buy a family ticket for 300 quid to visit the Domino’s Parthenon, where you can watch a parade of philosophers dressed as your favourite pizzas, with Pythagoras pepperoni proving a particular favourite, then scream your way down the Acropolis on a log flume.

One of the main demands in the final deal is that the Greek state must sell off €50bn-worth of its assets, which amounts to everything it has. This is part of the drive to make the economy stable and efficient. This works as long as you assume privatisation unarguably makes an industry more efficient. Obviously there are examples such as the railways in Britain, where privatisation has resulted in cheap reliable trains on which you can always get a seat, it’s easy to buy tickets across different rail networks, and customers are even offered delightful unscheduled 40-minute stops outside London Bridge station to give you the opportunity to paint the view of a gasworks in Bermondsey.

The demands placed on Greece are so extreme that even the International Monetary Fund has declared them “unsustainable”. The IMF is the body that has spent 50 years forcing countries such as Tanzania and Haiti to cut wages and sell off its possessions, in return for loans it needs so it can pay off the interest on the last lot of money it borrowed (from the IMF). So when it says the demands on Greece are too harsh, it’s like making the leader of Isis say, “Steady on, that’s a bit too Islamic”.

Still, someone has to tell the Greeks they can’t expect to carry on getting something for nothing. And the European Central Bank and national central banks – who, according to the Jubilee Debt Campaign, “stand to make between €10bn and €22bn out of Greek repayments” – are exactly the right people to deliver that stern but fair message.

Christine Lagarde, managing director of the IMF, is paid a salary of €550,000 a year, and by special arrangement pays no tax on that whatsoever. So she’s certainly the right person to lecture the Greeks, because she’s never been behind on her tax payments once. Every month she dutifully pays her nothing bang on time; she understands the importance of behaving responsibly with public money.

The most perplexing part of this story is that, a few days ago, it seemed as if Alexis Tsipras and his party, Syriza, were set to resist the orders being thrown at them, especially as they’d gone to the trouble of winning a referendum on whether to accept the EU demands. I suppose Tsipras thought that when the majority of Greeks voted against, it was because they felt those demands weren’t harsh enough, and they deserved to be punished much more severely as they’d all been very naughty.

Because Tsipras went into negotiations making it clear he was desperate to keep Greece in the eurozone, the EU could demand whatever it liked, knowing he’d accept anything rather than abandon the euro.

That sounds like going into a car showroom and saying, “I desperately need a car right now and I’ll have anything rather than leave without one”. A salesman could say, “We’ve only got this one, it’s got no engine and the windscreen’s made of wood and it pongs as a family of weasels live on the back seat and the bonnet’s on fire, it’s £10,000”, and you’d have no choice but to take it.

But maybe he did have a choice, to tell the banks they’ve made plenty out of Greece as it is and so, on balance, the elected government had decided to go along with what the Greeks voted for twice in a few months – wasting their money on schools and old people in villages, rather than do the sensible thing and hand over every coin as interest payments to institutions such as Goldman Sachs.

They’d have been kicked out of the eurozone, and probably out of Uefa and the Eurovision Song Contest, and scratched off the Inter-rail map too. But they’d have been a little beacon for everyone across Europe who feels the banks aren’t acting entirely in our interests, probably enough people to worry Angela Merkel just a bit.

What a relief that the Greeks have finally seen sense, and agreed to Angela Merkel’s demand that their Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras must scrub Berlin with a dishcloth, and crawl along the banks of the Rhine in a thong barking like a dog.

The week before he’d agreed to dress as a fairy and sing “The Good Ship Lollipop” while German children poked him with stinging nettles, but now that isn’t enough. So he has to accept even more measures essential to stabilising the Greek economy, such as being hosed down with kebab fat while naming the German squad that won the 1954 World Cup.

Otherwise, as EU leaders made clear, there would be no way Greece could stay inside the solar system; they’d have to orbit a different star in a faraway galaxy, which could be extremely damaging to the Greek tourist industry.

Instead of inviting further chaos by leaving Greece in the hands of the Greeks, their finances have been handed over entirely to the only people we can trust to behave responsibly at all times: the banks. Thank the Lord we’ve got at least one institution that has never behaved irresponsibly or recklessly in any way.

Perhaps the Greeks should have gone to Brussels and said they were rebranding Greece, so it’s no longer a country, but a bank. They’d have been bailed out by lunch and given a free set of steak knives as an extra gift. Instead they’ve got to sell off their entire country. By Christmas you’ll be able to buy a family ticket for 300 quid to visit the Domino’s Parthenon, where you can watch a parade of philosophers dressed as your favourite pizzas, with Pythagoras pepperoni proving a particular favourite, then scream your way down the Acropolis on a log flume.

One of the main demands in the final deal is that the Greek state must sell off €50bn-worth of its assets, which amounts to everything it has. This is part of the drive to make the economy stable and efficient. This works as long as you assume privatisation unarguably makes an industry more efficient. Obviously there are examples such as the railways in Britain, where privatisation has resulted in cheap reliable trains on which you can always get a seat, it’s easy to buy tickets across different rail networks, and customers are even offered delightful unscheduled 40-minute stops outside London Bridge station to give you the opportunity to paint the view of a gasworks in Bermondsey.

The demands placed on Greece are so extreme that even the International Monetary Fund has declared them “unsustainable”. The IMF is the body that has spent 50 years forcing countries such as Tanzania and Haiti to cut wages and sell off its possessions, in return for loans it needs so it can pay off the interest on the last lot of money it borrowed (from the IMF). So when it says the demands on Greece are too harsh, it’s like making the leader of Isis say, “Steady on, that’s a bit too Islamic”.

Still, someone has to tell the Greeks they can’t expect to carry on getting something for nothing. And the European Central Bank and national central banks – who, according to the Jubilee Debt Campaign, “stand to make between €10bn and €22bn out of Greek repayments” – are exactly the right people to deliver that stern but fair message.

Christine Lagarde, managing director of the IMF, is paid a salary of €550,000 a year, and by special arrangement pays no tax on that whatsoever. So she’s certainly the right person to lecture the Greeks, because she’s never been behind on her tax payments once. Every month she dutifully pays her nothing bang on time; she understands the importance of behaving responsibly with public money.

The most perplexing part of this story is that, a few days ago, it seemed as if Alexis Tsipras and his party, Syriza, were set to resist the orders being thrown at them, especially as they’d gone to the trouble of winning a referendum on whether to accept the EU demands. I suppose Tsipras thought that when the majority of Greeks voted against, it was because they felt those demands weren’t harsh enough, and they deserved to be punished much more severely as they’d all been very naughty.

Because Tsipras went into negotiations making it clear he was desperate to keep Greece in the eurozone, the EU could demand whatever it liked, knowing he’d accept anything rather than abandon the euro.

That sounds like going into a car showroom and saying, “I desperately need a car right now and I’ll have anything rather than leave without one”. A salesman could say, “We’ve only got this one, it’s got no engine and the windscreen’s made of wood and it pongs as a family of weasels live on the back seat and the bonnet’s on fire, it’s £10,000”, and you’d have no choice but to take it.

But maybe he did have a choice, to tell the banks they’ve made plenty out of Greece as it is and so, on balance, the elected government had decided to go along with what the Greeks voted for twice in a few months – wasting their money on schools and old people in villages, rather than do the sensible thing and hand over every coin as interest payments to institutions such as Goldman Sachs.

They’d have been kicked out of the eurozone, and probably out of Uefa and the Eurovision Song Contest, and scratched off the Inter-rail map too. But they’d have been a little beacon for everyone across Europe who feels the banks aren’t acting entirely in our interests, probably enough people to worry Angela Merkel just a bit.

Friday, 24 July 2015

How to think about Islamic State

Pankaj Mishra in The Guardian

Violence has erupted across a broad swath of territory in recent months: wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, suicide bombings in Xinjiang,Nigeria and Turkey, insurgencies from Yemen to Thailand, massacres in Paris, Tunisia and the American south. Future historians may well see such uncoordinated mayhem as commencing the third – and the longest and the strangest – of world wars. Certainly, forces larger and more complex than in the previous two wars are at work; they outrun our capacity to apprehend them, let alone adjust their direction to our benefit.

The early post cold war consensus – that bourgeois democracy has solved the riddle of history, and a global capitalist economy will usher in worldwide prosperity and peace – lies in tatters. But no plausible alternatives of political and economic organisation are in sight. A world organised for the play of individual self-interest looks more and more prone to manic tribalism.

In the lengthening spiral of mutinies from Charleston to central India, the insurgents of Iraq and Syria have monopolised our attention by their swift military victories; their exhibitionistic brutality, especially towards women and minorities; and, most significantly, their brisk seduction of young people from the cities of Europe and the US. Globalisation has everywhere rapidly weakened older forms of authority, in Europe’s social democracies as well as Arab despotisms, and thrown up an array of unpredictable new international actors, from Chinese irredentists and cyberhackers to Syriza and Boko Haram. But the sudden appearance of Islamic State (Isis) in Mosul last year, and the continuing failure to stem its expansion or check its appeal, is the clearest sign of a general perplexity, especially among political elites, who do not seem to know what they are doing and what they are bringing about.

In its capacity to invade and hold a territory the size of England, to inspire me-too zealotry in Pakistan, Gaza, Afghanistan, Nigeria, Libya and Egypt, and to entice thousands of camp followers, Isis represents a quantum leap over all other private and state-sanctioned cults of violence and authoritarianism today. But we are not faring well with the cognitive challenge to define this phenomenon.

For Obama, it is a “terrorist organisation, pure and simple”, which “we will degrade and ultimately destroy”. British politicians, yet again hoping against experience to impress the natives with a show of force, want to bomb the Levant as well as Mesopotamia. A sensationalist and scruple-free press seems eager to collude in their “noble lie”: that a Middle Eastern militia, thriving on the utter ineptitude of its local adversaries, poses an “existential risk” to an island fortress that saw off Napoleon and Hitler. The experts on Islam who opened for business on 9/11 peddle their wares more feverishly, helped by clash-of-civilisation theorists and other intellectual robots of the cold war, which were programmed to think in binaries (us versus them, free versus unfree world, Islam versus the west) and to limit their lexicon to words such as “ideology”, “threat” and “generational struggle”. The rash of pseudo-explanations – Islamism, Islamic extremism, Islamic fundamentalism, Islamic theology, Islamic irrationalism – makes Islam seem more than ever a concept in search of some content whilenormalising hatred and prejudice against more than 1.5 billion people. The abysmal intellectual deficit is summed up, on one hand, by the unremorsefullybellicose figure of Blair, and, on the other, the British government squabbling with the BBC over what to call Isis.

...

In the broadest view, Isis seems the product of a catastrophic war – the Anglo-American assault on Iraq. There is no doubt that the ground for it was prepared by this systematic devastation – the murder and displacement of millions, which came after more than a decade of brutalisation by sanctions and embargoes. The dismantling of the Iraqi army, de-Ba’athification and the Anglo-American imprimatur to Shia supremacism provoked the formation in Mesopotamia of al-Qaida, Isis’s precursor. Many local factors converged to make Isis’s emergence possible last year: vengeful Sunnis; reorganised Ba’athists in Iraq; the co-dependence of the west on despotic allies (al-Sisi, al-Maliki) and incoherence over Syria; the cynical manoeuvres of Assad; Turkey’s hubristic neo-Ottomanism, which seems exceeded in its recklessness only by the actions of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States.

The failure of the Arab Spring has also played a part. Tunisia, its originator, has sent the largest contingent of foreign jihadis to Iraq and Syria. Altogether an estimated 17,000 people, mostly young men, from 90 countries have travelled to Syria and Iraq to offer their services to Isis. Dozens of British women have gone, despite the fact that men of Isis have enslaved and raped girls as young as 10 years old, and stipulated that Muslim girls marry between the ages of nine and 17, and live in total seclusion. “You can easily earn yourself a higher station with God almighty,” a Canadian insurrectionist, Andre Poulin, exhorted in a video used by Isis for online recruitment, “by sacrificing just a small bit of this worldly life.”

It is not hard to see that populous countries such as Pakistan and Indonesia will always have a significant number of takers for well-paid martyrdom. What explains, however, the allure of a caliphate among thousands of residents of relatively prosperous and stable countries, such as the high-achieving London schoolgirls who travelled to Syria this spring?

Isis, the military phenomenon, could conceivably be degraded and destroyed. Or, it could rise further, fall abruptly and then rise again (like al-Qaida, which has been degraded and destroyed several times in recent years). The state can use its immense power to impound passports, shut down websites, and even enforce indoctrination in “British values” in schools. But this is no way to stem what seems a worldwide outbreak of intellectual and moral secessionism.

Isis is only one of its many beneficiaries; demagogues of all kinds have tapped the simmering reservoirs of cynicism and discontent. At the very least, their growing success and influence ought to make us re-examine our basic assumptions of order and continuity since the political and scientific revolutions of the 19th century – our belief that the human goods achieved so far by a fortunate minority can be realised by the ever-growing majority that desires them. We must ask if the millions of young people awakening around the world to their inheritance can realise the modern promise of freedom and prosperity. Or, are they doomed to lurch, like many others in the past, between a sense of inadequacy and fantasies of revenge?

...

Returning to Russia from Europe in 1862, Dostoevsky first began to explore at length the very modern torment of ressentiment that the misogynists of Twittertoday manifest as much as the dupes of Isis. Russian writers from Pushkin onwards had already probed the peculiar psychology of the “superfluous” man in a semi-westernised society: educated into a sense of hope and entitlement, but rendered adrift by his limited circumstances, and exposed to feelings of weakness, inferiority and envy. Russia, trying to catch up with the west, produced many such spiritually unmoored young men who had a quasi-Byronic conception of freedom, further inflated by German idealism, but the most unpromising conditions in which to realise them.

Rudin in Turgenev’s eponymous novel desperately wants to surrender himself “completely, greedily, utterly” to something; he ends up dead on a Parisian barricade in 1848, having sacrificed himself to a cause he doesn’t fully believe in. It was, however, Dostoevsky who saw most acutely how individuals, trained to believe in a lofty notion of personal freedom and sovereignty, and then confronted with a reality that cruelly cancelled it, could break out of paralysing ambivalence into gratuitous murder and paranoid insurgency.

His insight into this fateful gap between the theory and practice of liberal individualism developed during his travels in western Europe – the original site of the greatest social, political and economic transformations in human history, and the exemplar with its ideal of individual freedom for all of humanity. By the mid-19th century, Britain was the paradigmatic modern state and society, with its sights firmly set on industrial prosperity and commercial expansion. Visiting London in 1862, Dostoevsky quickly realised the world-historical import of what he was witnessing. “You become aware of a colossal idea,” he wrote after visiting the International Exhibition, showcase of an all-conquering material culture: “You sense that it would require great and everlasting spiritual denial and fortitude in order not to submit, not to capitulate before the impression, not to bow to what is, and not to deify Baal, that is, not to accept the material world as your ideal.”

However, as Dostoevsky saw it, the cost of such splendour and magnificence was a society dominated by the war of all against all, in which most people were condemned to be losers. In Paris, he caustically noted that liberté existed only for the millionaire. The notion of equality before the law was a “personal insult” to the poor exposed to French justice. As for fraternité, it was another hoax in a society driven by the “individualist, isolationist instinct” and the lust for private property.

Dostoevsky diagnosed the new project of human emancipation through the bewilderment and bitterness of people coming late to the modern world, and hoping to use its evidently successful ideas and methods to their advantage. For these naive latecomers, the gap between the noble ends of individual liberation and the poverty of available means in their barbarous social order was the greatest. The self-loathing clerk in Notes from Underground represents the human being who is excruciatingly aware that free moral choice is impossible in a world increasingly regimented by instrumental reason. He dreams constantly and impotently of revenge against his social superiors. Raskolnikov, the deracinated former law student in Crime and Punishment, is the psychopath of instrumental rationality, who can work up evidently logical reasons to do anything he desires. After murdering an old woman, he derives philosophical validation from the most celebrated nationalist and imperialist of his time, Napoleon: a “true master, to whom everything is permitted”.

...

The bloody dramas of political and economic laggards can seem remote from liberal-democratic Britain. The early and decisive winner in the sweepstakes of modern history has guaranteed an admirable measure of security, stability and dignity to many of its citizens. The parochial vision of modern history as essentially a conflict between open society and its enemies (liberal democracy versus nazism, communism and Islam) can feel accurate within the unbreached perimeters of Britain (and the US). It is not untrue to assert that Britain’s innovations and global reach spread the light of reason to the remotest corners of the Earth. Britain made the modern world in the sense that the forces it helped to originate – technology, economic organisation and science – formed a maelstrom that is still overwhelming millions of lives.

But this is also why Britain’s achievements cannot be seen in isolation from their ambiguous consequences elsewhere. Blaming Islamic theology, or fixating on the repellent rhetoric of Isis, may be indispensable in achieving moral self-entrancement, and toughening up convictions of superiority: we, liberal, democratic and rational, are not at all like these savages. But these spine-stiffening exercises can’t obscure the fact that Britain’s history has long been continuous with the world it made, which includes its ostensible enemies in Europe and beyond. Regardless of what the “island story” says, the belief systems and institutions Britain initiated – a global market economy, the nation state, utilitarian rationality – first caused a long emergency in Europe, before roiling the older worlds of Asia and Africa.

The recurrent crises explain why a range of figures, from Blake to Gandhi, and Simone Weil to Yukio Mishima, reacted remarkably similarly to the advent of industrial and commercial society, to the unprecedented phenomenon of all that is solid melting into thin air, across Europe, Asia and Africa.

“Spectres reign where no gods are,” Schiller wrote, deploring the atrophying of the “sacral sense” into nationalism and political power. Fear of moral and spiritual diminishment, and social chaos, was also a commonplace of much 19th-century British writing. “The rich have become richer, and the poor have become poorer; and the vessel of the state is driven between the Scylla and Charybdis of anarchy and despotism,” Shelley wrote in 1821, blaming inequality and disorder on the “unmitigated exercise of the calculating faculty”. Coleridge, denouncing “a contemptible democratical oligarchy of glib economists”, asked: “Is the increasing number of wealthy individuals that which ought to be understood by the wealth of the nation?” Dickens did much with Carlyle’s despairing insight into cash payment as the “sole nexus” between human beings. DH Lawrence recoiled fruitfully from “the base forcing of all human energy into a competition of mere acquisition”. Proximity to British arguments helped shape Marx’s vision of a proletariat goaded by the inequities and degradations of industrial capitalism into a revolutionary redemption of human existence.

The actual revolutions and revolts, however, occurred outside Britain, where liberal individualism, the product of a settled society with fixed social structures, seemed to have no answers to the plight of the uprooted masses living in squalor in cities. Its failure first motivated cultural nationalists, socialists, anarchists and revolutionaries across Europe, before seeding many anti-colonial movements in Asia and Africa. In an irony of modern history, which stalks revolutions and revolts to this day, the search for a new moral community has constantly assumed unpredicted and vicious forms. But then the dislocations and traumas caused by industralisation and urbanisation accelerated the growth of ideologies of race and blood in even enlightened western Europe.

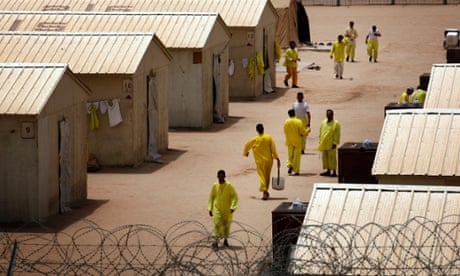

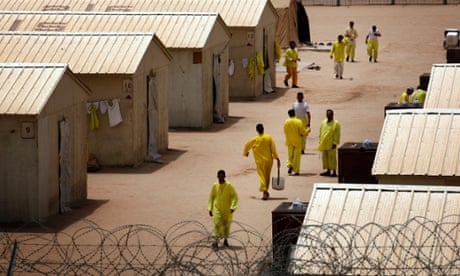

A militant Islamist fighter films a military parade in northern Syria celebrating the declaration of an Islamic caliphate. Photograph: Reuters

...

“The way of modern culture,” the Austrian writer Franz Grillparzer once lamented, “leads from humanity through nationality to bestiality.” He died too early (1872) to see another landmark en route to barbarism: modern European imperialism, whose humanitarian rhetoric was, like one of its representatives, Conrad’s Kurtz, “hollow at the core”.

In Asia, the usual disruptions of an industrial and commercial system that transcends political frontiers and destroys economic self-sufficiency, enslaving individuals to impersonal forces, were accompanied by a racist imperialism. The early victims and opponents of this ultra-aggressive modernity were local elites who organised their resistance around traditionalist loyalties and fantasies of recapturing a lost golden age – tendencies evident in the Boxer Rebellion in China as well as early 19th-century jihads against British rule in India.

Premodern political chieftains, who were long ago supplanted by western-educated men and women quoting John Stuart Mill and demanding individual rights, do not and cannot exist any more, however “Islamic” their theology may seem. They return today as parody – and there is much that is purely camp about a self-appointed caliph sporting a Rolex and India’s Hindu revivalist prime minister draped in a Savile Row $15,000 suit with personalised pin stripes. The spread of literacy, improved communications, rising populations and urbanisation have transformed the remotest corners of Asia and Africa. The desire for self-expansion through material success fully dominates the extant spiritual ideals of traditional religions and cultures.

Isis desperately tries to reinvent the early ideological antagonism between the imperialistic modern west and its traditionalist enemies. A recent issue of their magazine Dabiq approvingly quotes George W Bush’s us-versus-them exhortation, insisting that there is no “Gray Zone” in the holy war. Craving intellectual and political prestige, the DIY jihadists receive helpful endorsements from the self-proclaimed paladins of the west, such as Michael Gove, Britain’s leading American-style neocon. Responding to the revelation on 17 July of secret British bombing of Syria, Gove asserted that the “need to maintain the strengthand durability of the western alliance in the face of Islamist fundamentalism” can “trump everything”.

Clashing in the night, the ignorant armies of ideologues endow each other’s cherished self-conceptions with the veracity they crave. But their self-flattering oppositions collapse once we recognise that much violence today arises out of a heightened and continuously thwarted desire for convergence and resemblance rather than religious, cultural and theological difference.

The advent of the global economy in the 19th century, and its empowerment of a small island, caused an explosion of mimetic desire from western Europe to Japan. Since then, a sense of impotence and compensatory cultural pride has routinely driven the weak and marginalised to attack those that seem stronger than them while secretly desiring to possess their advantages. Humiliated rage and furtive envy characterise Muslim insurrectionaries and Hindu fanatics today as much as they did the militarist Japanese insisting on their unique spiritual quintessence. It is certainly not some esoteric 13th-century Hadith that makes Isis so eager to adopt the modern west’s technologies of war, revolution and propaganda – especially, as the homicidal dandyism of Jihadi John reveals, its mediatised shock-and-awe violence.

There is nothing remarkable about the fact that the biggest horde of foreign fighters in Iraq and Syria originated in Tunisia, the most westernised of Arab countries. Mass education, economic crisis and unfeeling government have long constituted a fertile soil for the cults of authoritarianism and violence. Powerlessness and deprivation are exacerbated today by the ability, boosted by digital media, to constantly compare your life with the lives of the fortunate (especially women entering the workforce or prominent in the public sphere: a common source of rage for men with siege mentalities worldwide). The quotient of frustration tends to be highest in countries that have a large population of educated young men who have undergone multiple shocks and displacements in their transition to modernity and yet find themselves unable to fulfil the promise of self-empowerment. For many of them the contradiction Dostoevsky noticed between extravagant promise and meagre means has become intolerable.

...

The sacral sense – the traditional basis of religion, entailing humility and self-restraint – has atrophied even where the churches, mosques and temples are full. The spectres of power reign incontestably where no gods are. Their triumph makes nonsense of the medieval-modern axis on which jihadis preening on Instagram in Halloween costumes are still reflexively defined. So extensive is the rout of pre-modern spiritual and metaphysical traditions that it is hard to even imagine their resurrection, let alone the restoration, on a necessarily large scale, of a non-instrumental view of human life (and the much-despoiled natural world). But there seem to be no political escape routes, either, out of the grisly cycle of retributive bombing and beheading.

The choice for many people in the early 20th century, as Rosa Luxemburgfamously proclaimed, was between socialism and barbarism. The German thinker spoke as the historical drama of the 19th century – revolution, nationalism, state-building, economic expansion, arms races, imperial aggrandisement – reached a disastrous denouement in the first world war. The choice has seemed less clear in the century since.

The mimic imperialisms of Japan and Germany, two resentful late-modernisers in Britain’s shadow, played out on a catastrophic scale the conflict built into the capitalist order. But socialist states committed to building human societies on co-operation rather than rivalry produced their own grotesqueries, as manifested byStalin and Mao and numerous regimes in the colonised world that sought moral advantage over their western masters by aiming at equality as well as prosperity.

Since 1989, the energies of postcolonial idealism have faded together with socialism as an economic and moral alternative. The unfettered globalisation of capital annexed more parts of the world into a uniform pattern of desire and consumption. The democratic revolution of aspiration De Tocqueville witnessed in the early 19th century swept across the world, sparking longings for wealth, status and power in the most unpromising circumstances. Equality of conditions, in which talent, education and hard work are rewarded by individual mobility, ceased to be an exclusively American illusion after 1989. It proliferated even as structural inequality entrenches itself further.

In the neoliberal fantasy of individualism, everyone was supposed to be an entrepreneur, retraining and repackaging themselves in a dynamic economy, perpetually alert to the latter’s technological revolutions. But capital continually moves across national boundaries in the search for profit, contemptuously sweeping skills and norms made obsolete by technology into the dustbin of history; and defeat and humiliation have become commonplace experiences in the strenuous endeavour of franchising the individual self.

Significantly numerous members of the precariat realise today that there is no such thing as a level playing field. The number of superfluous young people condemned to the anteroom of the modern world, an expanded Calais in its squalor and hopelessness, has grown exponentially in recent decades, especially in Asia and Africa’s youthful societies. The appeal of formal and informal secession – the possibility, broadly, of greater control over your life – has grown from Scotland to Hong Kong, beyond the cunningly separatist elites with multiple citizenship and offshore accounts. More and more people feel the gap between the profligate promises of individual freedom and sovereignty, and the incapacity of their political and economic organisations to realise them.

Even the nation state expressly designed to fulfil those promises – the United States – seethes with angry disillusionment across its class and racial divisions. A sense of victimhood festers among even relatively advantaged white men, as the rancorously popular candidacy of Donald Trump confirms. Elsewhere, the nasty discovery of Atticus Finch as a segregationist compounds the shock of Ferguson and Baltimore. Coming after decades of relentless and now insurmountable inequality, the revelation of long-standing systemic violence against African Americans is challenging some primary national myths and pieties. In a democracy founded by wealthy slave-owners and settler colonialists, and hollowed out by plutocrats, many citizens turn out to have never enjoyed equality of conditions. They raise the question that cuts through decades of liberal evasiveness about the cruelties of a political system intended to facilitate private moneymaking: “how to erect,” as Ta-Nehisi Coates puts it in his searing new book, Between the World and Me, “a democracy independent of cannibalism?”

And yet the obvious moral flaws of capitalism have not made it politically vulnerable. In the west, a common and effective response among regnant elites to unravelling national narratives and loss of legitimacy is fear-mongering among minorities and immigrants – an insidious campaign that continuously feeds on the hostility it provokes. These cosseted beneficiaries of an iniquitous order are also quick to ostracise the stray dissenter among them, as the case of Greece reveals. Chinese, Russian, Turkish and Indian leaders, who are also productively refurbishing their nation-building ideologies, have even less reason to oppose a global economic system that has helped enrich them and their cronies and allies.

Rather, Xi Jinping, Modi, Putin and Erdogan follow in the line of early 19th-century European and Japanese demagogues who responded to the many crises of capitalism by exhorting unity before internal and external threats. European or American-style imperialism is not a feasible option for them yet; they deploy instead, more riskily, jingoistic nationalism and cross-border militarism as a valve for domestic tensions. They have also retrofitted old-style nationalism for their growing populations of uprooted citizens, who harbour yearnings for belonging and community as well as material plenitude. Their self-legitimising narratives are necessarily hybrid: Mao-plus-Confucius, Holy Cow-plus-Smart Cities, Neoliberalism-plus-Islam, Putinism-plus-Orthodox Christianity.

...

‘Isis mobilises ressentiment into militant rebellion against the status quo’. Photograph: Reuters Photograph: Stringer . / Reuters/REUTERS

Isis, too, offers a postmodern collage rather than a determinate creed. Born in the ruins of two nation states that dissolved in sectarian violence, it vends the fantasy of a morally untainted and transnational caliphate. In actuality, Isis is the canniest of all traders in the flourishing international economy of disaffection: the most resourceful among all those who offer the security of collective identity to isolated and fearful individuals. It promises, along with others who retail racial, national and religious supremacy, to release the anxiety and frustrations of the private life into the violence of the global. Unlike its rivals, however, Isis mobilises ressentiment into militant rebellion against the status quo.

Isis mocks the entrepreneurial age’s imperative to project an appealing personality by posting snuff videos on social media. At the same time, it has a stern bureaucracy devoted to proper sanitation and tax collection. Some members of Isis extol the spiritual nobility of the Prophet and the earliest caliphs. Others confess through their mass rapes, choreographed murders and rational self-justifications a primary fealty to nihilism: that characteristically modern-day and insidiously common doctrine that makes it impossible for modern-day Raskolnikovs to deny themselves anything, and possible to justify anything.

The shapeshifting aspect of Isis is hardly unusual in a world in which “liberals” morph into warmongers, and “conservatives” institute revolutionary free-market “reforms”. Meanwhile, technocrats, while slashing employment and welfare benefits, and immiserating entire societies and generations, propose to bomb refugee boats, and secure unprecedented powers to imprison and snoop.

You can of course continue to insist on the rationality of liberal democracy as against “Islamic irrationalism” while waging infinite wars abroad and assaulting civil liberties at home. Such a conception of liberalism and democracy, however, will not only reveal its inability to offer wise representation to citizens. It will also make freshly relevant the question about intellectual and moral legitimacy raised by TS Eliot at a dark time in 1938, when he asked if “our society, which had always been so assured of its superiority and rectitude, so confident of its unexamined premises” was “assembled round anything more permanent than a congeries of banks, insurance companies and industries, and had it any beliefs more essential than a belief in compound interest and the maintenance of dividends?”

Today, the unmitigated exercise of the calculating faculty looks more indifferent to ordinary lives, and their need for belief and enchantment. The political impasses and economic shocks in our societies, and the irreparably damaged environment, corroborate the bleakest views of 19th-century critics who condemned modern capitalism as a heartless machinery for economic growth, or the enrichment of the few, which works against such fundamentally human aspirations as stability, community and a better future. Isis, among many others, draws its appeal from an incoherence of concepts – “democracy” and “individual rights” among them – with which many still reflexively shore up the ideological defences of a self-evidently dysfunctional system. The contradictions and costs of a tiny minority’s progress, long suppressed by blustery denial and aggressive equivocation, have become visible on a planetary scale. They encourage the suspicion – potentially lethal among the hundreds of millions of young people condemned to being superfluous – that the present order, democratic or authoritarian, is built on force and fraud; they incite a broader and more volatile apocalyptic and nihilistic mood than we have witnessed before. Professional politicians, and their intellectual menials, will no doubt blather on about “Islamic fundamentalism”, the “western alliance” and “full-spectrum response”. Much radical thinking, however, is required if we are to prevent ressentiment from erupting into even bigger conflagrations.

Violence has erupted across a broad swath of territory in recent months: wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, suicide bombings in Xinjiang,Nigeria and Turkey, insurgencies from Yemen to Thailand, massacres in Paris, Tunisia and the American south. Future historians may well see such uncoordinated mayhem as commencing the third – and the longest and the strangest – of world wars. Certainly, forces larger and more complex than in the previous two wars are at work; they outrun our capacity to apprehend them, let alone adjust their direction to our benefit.

The early post cold war consensus – that bourgeois democracy has solved the riddle of history, and a global capitalist economy will usher in worldwide prosperity and peace – lies in tatters. But no plausible alternatives of political and economic organisation are in sight. A world organised for the play of individual self-interest looks more and more prone to manic tribalism.

In the lengthening spiral of mutinies from Charleston to central India, the insurgents of Iraq and Syria have monopolised our attention by their swift military victories; their exhibitionistic brutality, especially towards women and minorities; and, most significantly, their brisk seduction of young people from the cities of Europe and the US. Globalisation has everywhere rapidly weakened older forms of authority, in Europe’s social democracies as well as Arab despotisms, and thrown up an array of unpredictable new international actors, from Chinese irredentists and cyberhackers to Syriza and Boko Haram. But the sudden appearance of Islamic State (Isis) in Mosul last year, and the continuing failure to stem its expansion or check its appeal, is the clearest sign of a general perplexity, especially among political elites, who do not seem to know what they are doing and what they are bringing about.

In its capacity to invade and hold a territory the size of England, to inspire me-too zealotry in Pakistan, Gaza, Afghanistan, Nigeria, Libya and Egypt, and to entice thousands of camp followers, Isis represents a quantum leap over all other private and state-sanctioned cults of violence and authoritarianism today. But we are not faring well with the cognitive challenge to define this phenomenon.

For Obama, it is a “terrorist organisation, pure and simple”, which “we will degrade and ultimately destroy”. British politicians, yet again hoping against experience to impress the natives with a show of force, want to bomb the Levant as well as Mesopotamia. A sensationalist and scruple-free press seems eager to collude in their “noble lie”: that a Middle Eastern militia, thriving on the utter ineptitude of its local adversaries, poses an “existential risk” to an island fortress that saw off Napoleon and Hitler. The experts on Islam who opened for business on 9/11 peddle their wares more feverishly, helped by clash-of-civilisation theorists and other intellectual robots of the cold war, which were programmed to think in binaries (us versus them, free versus unfree world, Islam versus the west) and to limit their lexicon to words such as “ideology”, “threat” and “generational struggle”. The rash of pseudo-explanations – Islamism, Islamic extremism, Islamic fundamentalism, Islamic theology, Islamic irrationalism – makes Islam seem more than ever a concept in search of some content whilenormalising hatred and prejudice against more than 1.5 billion people. The abysmal intellectual deficit is summed up, on one hand, by the unremorsefullybellicose figure of Blair, and, on the other, the British government squabbling with the BBC over what to call Isis.

...

In the broadest view, Isis seems the product of a catastrophic war – the Anglo-American assault on Iraq. There is no doubt that the ground for it was prepared by this systematic devastation – the murder and displacement of millions, which came after more than a decade of brutalisation by sanctions and embargoes. The dismantling of the Iraqi army, de-Ba’athification and the Anglo-American imprimatur to Shia supremacism provoked the formation in Mesopotamia of al-Qaida, Isis’s precursor. Many local factors converged to make Isis’s emergence possible last year: vengeful Sunnis; reorganised Ba’athists in Iraq; the co-dependence of the west on despotic allies (al-Sisi, al-Maliki) and incoherence over Syria; the cynical manoeuvres of Assad; Turkey’s hubristic neo-Ottomanism, which seems exceeded in its recklessness only by the actions of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States.

The failure of the Arab Spring has also played a part. Tunisia, its originator, has sent the largest contingent of foreign jihadis to Iraq and Syria. Altogether an estimated 17,000 people, mostly young men, from 90 countries have travelled to Syria and Iraq to offer their services to Isis. Dozens of British women have gone, despite the fact that men of Isis have enslaved and raped girls as young as 10 years old, and stipulated that Muslim girls marry between the ages of nine and 17, and live in total seclusion. “You can easily earn yourself a higher station with God almighty,” a Canadian insurrectionist, Andre Poulin, exhorted in a video used by Isis for online recruitment, “by sacrificing just a small bit of this worldly life.”

It is not hard to see that populous countries such as Pakistan and Indonesia will always have a significant number of takers for well-paid martyrdom. What explains, however, the allure of a caliphate among thousands of residents of relatively prosperous and stable countries, such as the high-achieving London schoolgirls who travelled to Syria this spring?

Isis, the military phenomenon, could conceivably be degraded and destroyed. Or, it could rise further, fall abruptly and then rise again (like al-Qaida, which has been degraded and destroyed several times in recent years). The state can use its immense power to impound passports, shut down websites, and even enforce indoctrination in “British values” in schools. But this is no way to stem what seems a worldwide outbreak of intellectual and moral secessionism.

Isis is only one of its many beneficiaries; demagogues of all kinds have tapped the simmering reservoirs of cynicism and discontent. At the very least, their growing success and influence ought to make us re-examine our basic assumptions of order and continuity since the political and scientific revolutions of the 19th century – our belief that the human goods achieved so far by a fortunate minority can be realised by the ever-growing majority that desires them. We must ask if the millions of young people awakening around the world to their inheritance can realise the modern promise of freedom and prosperity. Or, are they doomed to lurch, like many others in the past, between a sense of inadequacy and fantasies of revenge?

...

Returning to Russia from Europe in 1862, Dostoevsky first began to explore at length the very modern torment of ressentiment that the misogynists of Twittertoday manifest as much as the dupes of Isis. Russian writers from Pushkin onwards had already probed the peculiar psychology of the “superfluous” man in a semi-westernised society: educated into a sense of hope and entitlement, but rendered adrift by his limited circumstances, and exposed to feelings of weakness, inferiority and envy. Russia, trying to catch up with the west, produced many such spiritually unmoored young men who had a quasi-Byronic conception of freedom, further inflated by German idealism, but the most unpromising conditions in which to realise them.

Rudin in Turgenev’s eponymous novel desperately wants to surrender himself “completely, greedily, utterly” to something; he ends up dead on a Parisian barricade in 1848, having sacrificed himself to a cause he doesn’t fully believe in. It was, however, Dostoevsky who saw most acutely how individuals, trained to believe in a lofty notion of personal freedom and sovereignty, and then confronted with a reality that cruelly cancelled it, could break out of paralysing ambivalence into gratuitous murder and paranoid insurgency.

His insight into this fateful gap between the theory and practice of liberal individualism developed during his travels in western Europe – the original site of the greatest social, political and economic transformations in human history, and the exemplar with its ideal of individual freedom for all of humanity. By the mid-19th century, Britain was the paradigmatic modern state and society, with its sights firmly set on industrial prosperity and commercial expansion. Visiting London in 1862, Dostoevsky quickly realised the world-historical import of what he was witnessing. “You become aware of a colossal idea,” he wrote after visiting the International Exhibition, showcase of an all-conquering material culture: “You sense that it would require great and everlasting spiritual denial and fortitude in order not to submit, not to capitulate before the impression, not to bow to what is, and not to deify Baal, that is, not to accept the material world as your ideal.”

However, as Dostoevsky saw it, the cost of such splendour and magnificence was a society dominated by the war of all against all, in which most people were condemned to be losers. In Paris, he caustically noted that liberté existed only for the millionaire. The notion of equality before the law was a “personal insult” to the poor exposed to French justice. As for fraternité, it was another hoax in a society driven by the “individualist, isolationist instinct” and the lust for private property.

Dostoevsky diagnosed the new project of human emancipation through the bewilderment and bitterness of people coming late to the modern world, and hoping to use its evidently successful ideas and methods to their advantage. For these naive latecomers, the gap between the noble ends of individual liberation and the poverty of available means in their barbarous social order was the greatest. The self-loathing clerk in Notes from Underground represents the human being who is excruciatingly aware that free moral choice is impossible in a world increasingly regimented by instrumental reason. He dreams constantly and impotently of revenge against his social superiors. Raskolnikov, the deracinated former law student in Crime and Punishment, is the psychopath of instrumental rationality, who can work up evidently logical reasons to do anything he desires. After murdering an old woman, he derives philosophical validation from the most celebrated nationalist and imperialist of his time, Napoleon: a “true master, to whom everything is permitted”.

...

The bloody dramas of political and economic laggards can seem remote from liberal-democratic Britain. The early and decisive winner in the sweepstakes of modern history has guaranteed an admirable measure of security, stability and dignity to many of its citizens. The parochial vision of modern history as essentially a conflict between open society and its enemies (liberal democracy versus nazism, communism and Islam) can feel accurate within the unbreached perimeters of Britain (and the US). It is not untrue to assert that Britain’s innovations and global reach spread the light of reason to the remotest corners of the Earth. Britain made the modern world in the sense that the forces it helped to originate – technology, economic organisation and science – formed a maelstrom that is still overwhelming millions of lives.

But this is also why Britain’s achievements cannot be seen in isolation from their ambiguous consequences elsewhere. Blaming Islamic theology, or fixating on the repellent rhetoric of Isis, may be indispensable in achieving moral self-entrancement, and toughening up convictions of superiority: we, liberal, democratic and rational, are not at all like these savages. But these spine-stiffening exercises can’t obscure the fact that Britain’s history has long been continuous with the world it made, which includes its ostensible enemies in Europe and beyond. Regardless of what the “island story” says, the belief systems and institutions Britain initiated – a global market economy, the nation state, utilitarian rationality – first caused a long emergency in Europe, before roiling the older worlds of Asia and Africa.

The recurrent crises explain why a range of figures, from Blake to Gandhi, and Simone Weil to Yukio Mishima, reacted remarkably similarly to the advent of industrial and commercial society, to the unprecedented phenomenon of all that is solid melting into thin air, across Europe, Asia and Africa.

“Spectres reign where no gods are,” Schiller wrote, deploring the atrophying of the “sacral sense” into nationalism and political power. Fear of moral and spiritual diminishment, and social chaos, was also a commonplace of much 19th-century British writing. “The rich have become richer, and the poor have become poorer; and the vessel of the state is driven between the Scylla and Charybdis of anarchy and despotism,” Shelley wrote in 1821, blaming inequality and disorder on the “unmitigated exercise of the calculating faculty”. Coleridge, denouncing “a contemptible democratical oligarchy of glib economists”, asked: “Is the increasing number of wealthy individuals that which ought to be understood by the wealth of the nation?” Dickens did much with Carlyle’s despairing insight into cash payment as the “sole nexus” between human beings. DH Lawrence recoiled fruitfully from “the base forcing of all human energy into a competition of mere acquisition”. Proximity to British arguments helped shape Marx’s vision of a proletariat goaded by the inequities and degradations of industrial capitalism into a revolutionary redemption of human existence.

The actual revolutions and revolts, however, occurred outside Britain, where liberal individualism, the product of a settled society with fixed social structures, seemed to have no answers to the plight of the uprooted masses living in squalor in cities. Its failure first motivated cultural nationalists, socialists, anarchists and revolutionaries across Europe, before seeding many anti-colonial movements in Asia and Africa. In an irony of modern history, which stalks revolutions and revolts to this day, the search for a new moral community has constantly assumed unpredicted and vicious forms. But then the dislocations and traumas caused by industralisation and urbanisation accelerated the growth of ideologies of race and blood in even enlightened western Europe.

A militant Islamist fighter films a military parade in northern Syria celebrating the declaration of an Islamic caliphate. Photograph: Reuters

...

“The way of modern culture,” the Austrian writer Franz Grillparzer once lamented, “leads from humanity through nationality to bestiality.” He died too early (1872) to see another landmark en route to barbarism: modern European imperialism, whose humanitarian rhetoric was, like one of its representatives, Conrad’s Kurtz, “hollow at the core”.

In Asia, the usual disruptions of an industrial and commercial system that transcends political frontiers and destroys economic self-sufficiency, enslaving individuals to impersonal forces, were accompanied by a racist imperialism. The early victims and opponents of this ultra-aggressive modernity were local elites who organised their resistance around traditionalist loyalties and fantasies of recapturing a lost golden age – tendencies evident in the Boxer Rebellion in China as well as early 19th-century jihads against British rule in India.

Premodern political chieftains, who were long ago supplanted by western-educated men and women quoting John Stuart Mill and demanding individual rights, do not and cannot exist any more, however “Islamic” their theology may seem. They return today as parody – and there is much that is purely camp about a self-appointed caliph sporting a Rolex and India’s Hindu revivalist prime minister draped in a Savile Row $15,000 suit with personalised pin stripes. The spread of literacy, improved communications, rising populations and urbanisation have transformed the remotest corners of Asia and Africa. The desire for self-expansion through material success fully dominates the extant spiritual ideals of traditional religions and cultures.

Isis desperately tries to reinvent the early ideological antagonism between the imperialistic modern west and its traditionalist enemies. A recent issue of their magazine Dabiq approvingly quotes George W Bush’s us-versus-them exhortation, insisting that there is no “Gray Zone” in the holy war. Craving intellectual and political prestige, the DIY jihadists receive helpful endorsements from the self-proclaimed paladins of the west, such as Michael Gove, Britain’s leading American-style neocon. Responding to the revelation on 17 July of secret British bombing of Syria, Gove asserted that the “need to maintain the strengthand durability of the western alliance in the face of Islamist fundamentalism” can “trump everything”.

Clashing in the night, the ignorant armies of ideologues endow each other’s cherished self-conceptions with the veracity they crave. But their self-flattering oppositions collapse once we recognise that much violence today arises out of a heightened and continuously thwarted desire for convergence and resemblance rather than religious, cultural and theological difference.

The advent of the global economy in the 19th century, and its empowerment of a small island, caused an explosion of mimetic desire from western Europe to Japan. Since then, a sense of impotence and compensatory cultural pride has routinely driven the weak and marginalised to attack those that seem stronger than them while secretly desiring to possess their advantages. Humiliated rage and furtive envy characterise Muslim insurrectionaries and Hindu fanatics today as much as they did the militarist Japanese insisting on their unique spiritual quintessence. It is certainly not some esoteric 13th-century Hadith that makes Isis so eager to adopt the modern west’s technologies of war, revolution and propaganda – especially, as the homicidal dandyism of Jihadi John reveals, its mediatised shock-and-awe violence.

There is nothing remarkable about the fact that the biggest horde of foreign fighters in Iraq and Syria originated in Tunisia, the most westernised of Arab countries. Mass education, economic crisis and unfeeling government have long constituted a fertile soil for the cults of authoritarianism and violence. Powerlessness and deprivation are exacerbated today by the ability, boosted by digital media, to constantly compare your life with the lives of the fortunate (especially women entering the workforce or prominent in the public sphere: a common source of rage for men with siege mentalities worldwide). The quotient of frustration tends to be highest in countries that have a large population of educated young men who have undergone multiple shocks and displacements in their transition to modernity and yet find themselves unable to fulfil the promise of self-empowerment. For many of them the contradiction Dostoevsky noticed between extravagant promise and meagre means has become intolerable.

...

The sacral sense – the traditional basis of religion, entailing humility and self-restraint – has atrophied even where the churches, mosques and temples are full. The spectres of power reign incontestably where no gods are. Their triumph makes nonsense of the medieval-modern axis on which jihadis preening on Instagram in Halloween costumes are still reflexively defined. So extensive is the rout of pre-modern spiritual and metaphysical traditions that it is hard to even imagine their resurrection, let alone the restoration, on a necessarily large scale, of a non-instrumental view of human life (and the much-despoiled natural world). But there seem to be no political escape routes, either, out of the grisly cycle of retributive bombing and beheading.

The choice for many people in the early 20th century, as Rosa Luxemburgfamously proclaimed, was between socialism and barbarism. The German thinker spoke as the historical drama of the 19th century – revolution, nationalism, state-building, economic expansion, arms races, imperial aggrandisement – reached a disastrous denouement in the first world war. The choice has seemed less clear in the century since.

The mimic imperialisms of Japan and Germany, two resentful late-modernisers in Britain’s shadow, played out on a catastrophic scale the conflict built into the capitalist order. But socialist states committed to building human societies on co-operation rather than rivalry produced their own grotesqueries, as manifested byStalin and Mao and numerous regimes in the colonised world that sought moral advantage over their western masters by aiming at equality as well as prosperity.

Since 1989, the energies of postcolonial idealism have faded together with socialism as an economic and moral alternative. The unfettered globalisation of capital annexed more parts of the world into a uniform pattern of desire and consumption. The democratic revolution of aspiration De Tocqueville witnessed in the early 19th century swept across the world, sparking longings for wealth, status and power in the most unpromising circumstances. Equality of conditions, in which talent, education and hard work are rewarded by individual mobility, ceased to be an exclusively American illusion after 1989. It proliferated even as structural inequality entrenches itself further.

In the neoliberal fantasy of individualism, everyone was supposed to be an entrepreneur, retraining and repackaging themselves in a dynamic economy, perpetually alert to the latter’s technological revolutions. But capital continually moves across national boundaries in the search for profit, contemptuously sweeping skills and norms made obsolete by technology into the dustbin of history; and defeat and humiliation have become commonplace experiences in the strenuous endeavour of franchising the individual self.

Significantly numerous members of the precariat realise today that there is no such thing as a level playing field. The number of superfluous young people condemned to the anteroom of the modern world, an expanded Calais in its squalor and hopelessness, has grown exponentially in recent decades, especially in Asia and Africa’s youthful societies. The appeal of formal and informal secession – the possibility, broadly, of greater control over your life – has grown from Scotland to Hong Kong, beyond the cunningly separatist elites with multiple citizenship and offshore accounts. More and more people feel the gap between the profligate promises of individual freedom and sovereignty, and the incapacity of their political and economic organisations to realise them.

Even the nation state expressly designed to fulfil those promises – the United States – seethes with angry disillusionment across its class and racial divisions. A sense of victimhood festers among even relatively advantaged white men, as the rancorously popular candidacy of Donald Trump confirms. Elsewhere, the nasty discovery of Atticus Finch as a segregationist compounds the shock of Ferguson and Baltimore. Coming after decades of relentless and now insurmountable inequality, the revelation of long-standing systemic violence against African Americans is challenging some primary national myths and pieties. In a democracy founded by wealthy slave-owners and settler colonialists, and hollowed out by plutocrats, many citizens turn out to have never enjoyed equality of conditions. They raise the question that cuts through decades of liberal evasiveness about the cruelties of a political system intended to facilitate private moneymaking: “how to erect,” as Ta-Nehisi Coates puts it in his searing new book, Between the World and Me, “a democracy independent of cannibalism?”

And yet the obvious moral flaws of capitalism have not made it politically vulnerable. In the west, a common and effective response among regnant elites to unravelling national narratives and loss of legitimacy is fear-mongering among minorities and immigrants – an insidious campaign that continuously feeds on the hostility it provokes. These cosseted beneficiaries of an iniquitous order are also quick to ostracise the stray dissenter among them, as the case of Greece reveals. Chinese, Russian, Turkish and Indian leaders, who are also productively refurbishing their nation-building ideologies, have even less reason to oppose a global economic system that has helped enrich them and their cronies and allies.

Rather, Xi Jinping, Modi, Putin and Erdogan follow in the line of early 19th-century European and Japanese demagogues who responded to the many crises of capitalism by exhorting unity before internal and external threats. European or American-style imperialism is not a feasible option for them yet; they deploy instead, more riskily, jingoistic nationalism and cross-border militarism as a valve for domestic tensions. They have also retrofitted old-style nationalism for their growing populations of uprooted citizens, who harbour yearnings for belonging and community as well as material plenitude. Their self-legitimising narratives are necessarily hybrid: Mao-plus-Confucius, Holy Cow-plus-Smart Cities, Neoliberalism-plus-Islam, Putinism-plus-Orthodox Christianity.

...

‘Isis mobilises ressentiment into militant rebellion against the status quo’. Photograph: Reuters Photograph: Stringer . / Reuters/REUTERS

Isis, too, offers a postmodern collage rather than a determinate creed. Born in the ruins of two nation states that dissolved in sectarian violence, it vends the fantasy of a morally untainted and transnational caliphate. In actuality, Isis is the canniest of all traders in the flourishing international economy of disaffection: the most resourceful among all those who offer the security of collective identity to isolated and fearful individuals. It promises, along with others who retail racial, national and religious supremacy, to release the anxiety and frustrations of the private life into the violence of the global. Unlike its rivals, however, Isis mobilises ressentiment into militant rebellion against the status quo.