Two academics hold Gujarat up against other states to see if it grew more in the Modi decade than in the preceding 20 years

The forthcoming election, it seems, will be fought mainly on issues of governance and economic performance. To the extent there is a focus on the personalities involved, such as Narendra Modi or Rahul Gandhi or Arvind Kejriwal or potential ‘Third Front’ candidates such as Nitish Kumar or Mamata Banerjee, most of the discussion is about their economic track record or lack thereof. This is a welcome development. However, in the grand theatre of Indian politics, facts often take a backseat to slogans, and opinions get sharply polarised. For example, we either hear that Gujarat’s economic performance has been nothing short of miraculous due to the magic touch of Modi or that Gujarat’s so-called growth story is all hype and a PR campaign aimed at covering up a dark underbelly of poverty, inequality and low levels of human development indicators.

A lot of this debate reflects disagreements about two sets of issues. First, there are many dimensions of economic performance—we could look at the level of per capita income, the growth rate of per capita income, human development indices (HDI) that put weight on not only income but also on non-income measures like education and health, the level of inequality, percentage of people below the poverty line, and many others. Which index we choose to emphasise reflects either our preferences as to the aspect of economic performance we value the most, or our views as to which dimension has to be improved (say, per capita income) for bettering the dimension we care about (say, poverty alleviation).

A lot of this debate reflects disagreements about two sets of issues. First, there are many dimensions of economic performance—we could look at the level of per capita income, the growth rate of per capita income, human development indices (HDI) that put weight on not only income but also on non-income measures like education and health, the level of inequality, percentage of people below the poverty line, and many others. Which index we choose to emphasise reflects either our preferences as to the aspect of economic performance we value the most, or our views as to which dimension has to be improved (say, per capita income) for bettering the dimension we care about (say, poverty alleviation).

Secondly, even if we focus on one particular dimension of economic performance, how do we attribute changes in this dimension to the role of a specific leader? For example, how do we isolate the contribution of Narendra Modi and Nitish Kumar to the growth of Gujarat and Bihar, respectively, in the 2000s, especially as the country as a whole experienced a growth spurt in this period?

Therefore, the first issue is how to separate the leader’s contribution from other factors driving his or her state’s performance, for example, a general improvement in the economic environment of the country that benefits all states. The solution to this problem is to calculate the difference between the growth rate of the state for the years this leader was in power and the average growth rate of the rest of the states during the same period of time. If this difference is positive, then it is safe to say that the state under this leader grew faster than the rest of the country.

However, this is not enough. What if the state in question was always growing faster than the rest of the country? How can we then isolate the specific role of this leader?

To give an analogy, to show that a company’s performance under a new CEO has improved, it is not sufficient to show that the performance of the firm has been above average relative to that of other firms after the new CEO took over, as it is possible that this firm was already ahead of others. Similarly, if we find that a firm beat its past record under the new management, we cannot automatically attribute this to the CEO, as it is possible that all firms performed better in this period due to positive changes in the economic environment. To claim that this CEO had a transformative impact on the firm, we need to show not only that this firm stayed ahead of other firms after he took over but that its performance margin relative to other firms improved significantly under him.

Thus, returning to the example of Modi, in order to claim that his leadership had a significant impact on Gujarat’s economic performance, it is not enough to show that the state did better than the rest of India after he came to power in 2001. We have to demonstrate that the gap between Gujarat’s performance and that of the rest of India actually increased under his rule. This is a statistical method called ‘differences in differences’. It is routinely used to evaluate the performance of organisations under a particular management or the effectiveness of a particular government policy.

Turning to evidence, we look at the following key indices of economic performance—level of per capita income, its growth rate, HDI, inequality and the percentage of population below the poverty line—for the major Indian states. All through, we have focused on the major 16 states in terms of population. The larger a state, the harder it is to achieve improvements in per capita average economic indicators. Therefore, comparing a large state like Uttar Pradesh and a small one like Nagaland can be misleading; it is better to compare like with like. However, we have to keep in mind that even among the major states, turning around a state with a larger population is a harder task.

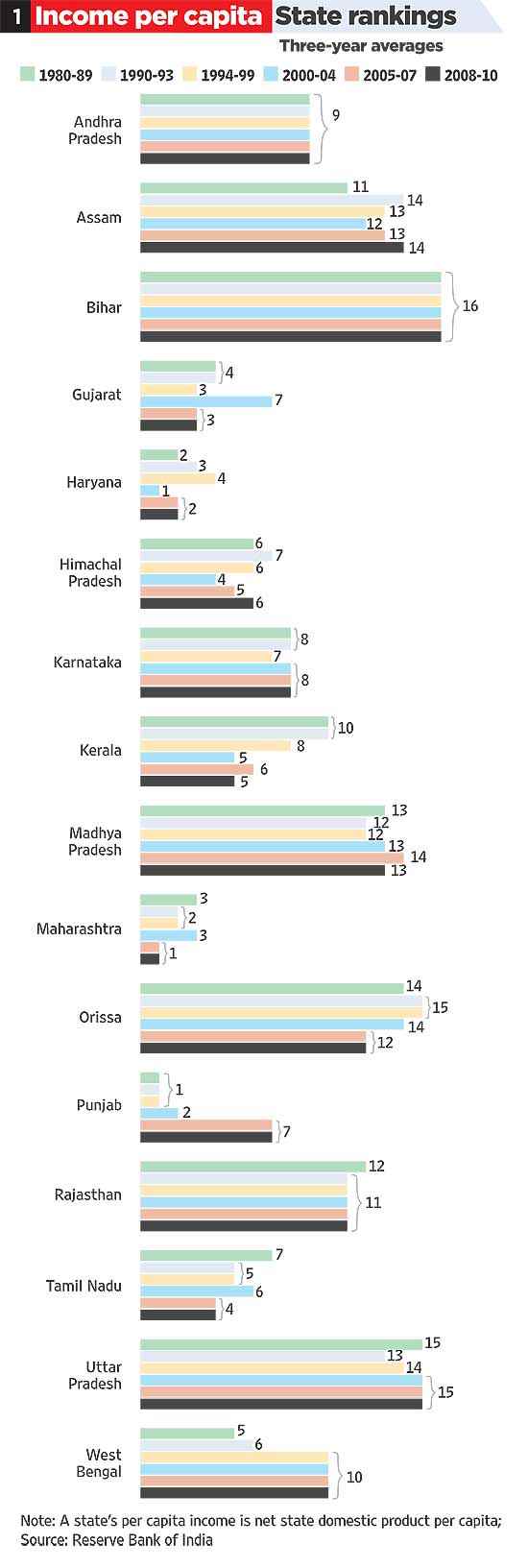

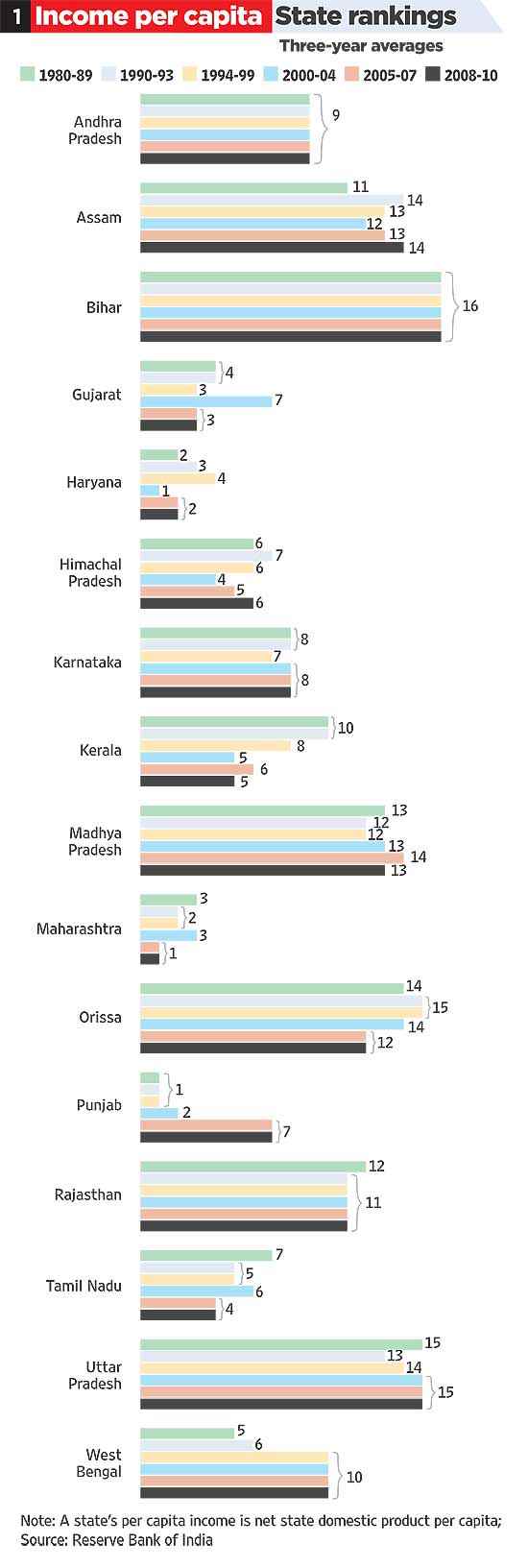

We begin by looking at the most obvious economic indicator—the level of per capita income. In terms of average per capita income ranking of states over the 1980s, ’90s and 2000s, the top three states are Haryana, Punjab and Maharashtra (see Table 1). Gujarat’s average rank is 4. On the other hand, Bihar, which has been in the news lately due to its spectacular turnaround over the recent years under the leadership of Nitish Kumar, has been consistently at the bottom of this league with a rank of 16, below UP, which too has remained steady at number 15.

In terms of improving their relative ranking over the three decades, the top performers among the leading states are Maharashtra, Gujarat, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Between the ’80s and now, Maharashtra has moved from 3 to 1, Gujarat from 4 to 3, Kerala from 10 to 5 and Tamil Nadu from 7 to 4. Interestingly, the rise in the ranks of these four has been accompanied by the relative decline of Punjab, which went from being the very top state in the ’80s and ’90s to No. 7 in 2010. This suggests that, as in athletic races, the relative rank of a state may go up or down either due to a change in its own performance or due to a change in the rival’s performance.

Thus, to obtain a fuller picture of the economic performance of these states, we also need to consider their relative growth performances. The relative ranking at a given point of time as in Table 1 gives only a snapshot of where states stand in terms of economic performance. But as we know from athletic races, unless that point happens to be the finishing line, it is the rate at which an athlete is accelerating that determines the final outcome. While there is no final finishing line in the race of economic development, the current growth performance of a state can give an indication of its potential position in the future. Is the rise in rankings of states like Maharashtra and Gujarat also matched by a faster growth rate on their part? Also, are there states that are lower down in the ranking but are growing faster than average and so can hope to improve their ranking in the future?

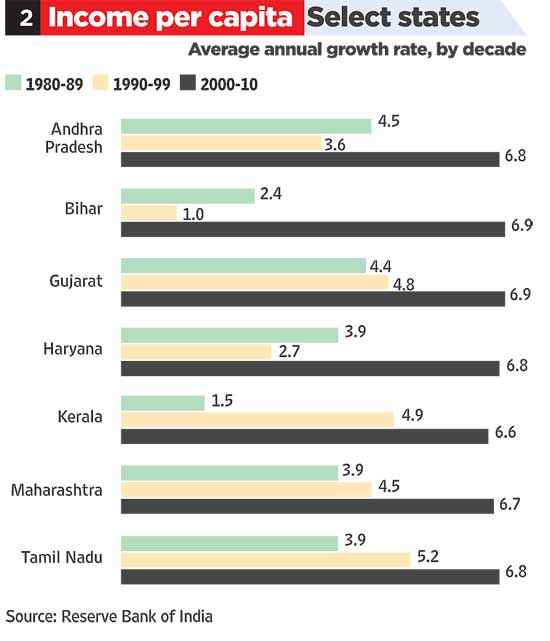

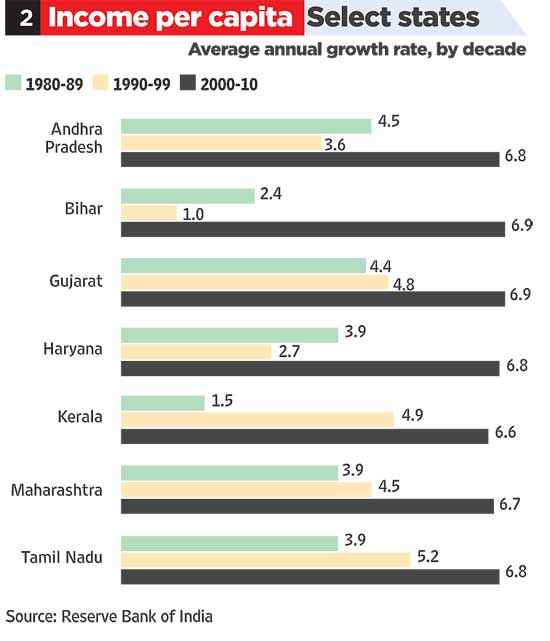

Table 2 documents the annual average growth rates of states which have performed better than national average (leaders) in each of the three decades. Only three states have had above average growth performance in all three decades: Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. They were joined by Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana and Kerala in the 2000s.

Interestingly, the growth rate of Punjab, initially one of the top-ranked states in terms of per capita income level, has been below the national average in the last two decades. Thus it is not surprising that it is slipping down in rank below other faster-growing states. Bihar, on the other hand, is poised to rise up the ranks with a higher than average growth rate of per capita income in the 2000s. In a way, Bihar’s story is the opposite of Punjab’s: while it is still at the bottom of the chart in terms of the level of per capita income, it can expect to improve its rank if it maintains its recent high growth rate.

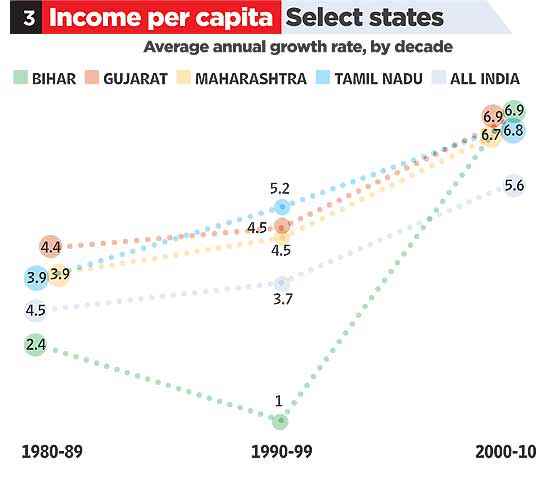

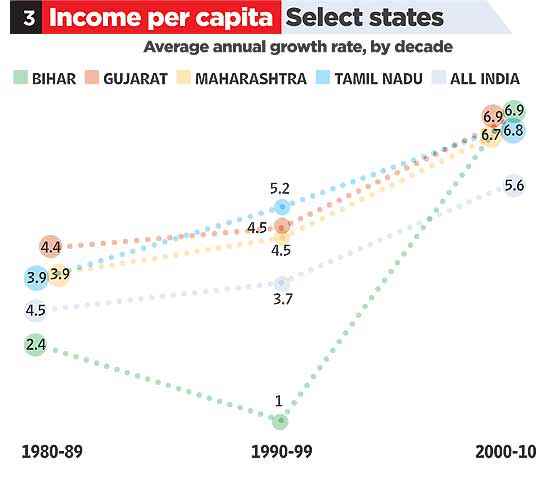

Now we come to one of the key questions. Which are the states that improved their performance in the 2000s both with respect to their past performance in the earlier two decades, and with respect to the performance of other states in the 2000s? Table 3 graphically plots the average annual growth rates of five states against the national average over time. This graph shows an interesting trend: while Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra have been going neck and neck (and Haryana, which is not shown in the figure), and as already mentioned, have consistently performed above the national average, none of them has experienced a huge acceleration in growth rate in the 2000s. In contrast, Bihar, which was consistently doing worse than the national average through the ’80s and ’90s, shot up above the national average in the 2000s, converging to rates achieved by established leaders like Gujarat, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu.

To sum up, we see that Maharashtra, Haryana, Punjab, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu have been among the richest states in the last three decades. In the 2000s, the big news was Punjab dropping from the top 5 and Kerala breaking into this select group. Among the rest, Maharashtra ended as the topper in the latter half of the 2000s, and Gujarat at a very respectable number 3, after Haryana. In terms of growth performance, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra were the toppers over the last three decades but in the 2000s, three other states raised their game to join the list of fastest-growing states: Bihar, Haryana and Andhra Pradesh. However, if any state could claim that its performance relative to the rest of India actually improved in the 2000s, that state is Bihar.

Therefore, if awards must be given, Bihar deserves the prize for the most dramatic turnaround in the 2000s. Gujarat gets credit for having steadily been on top of the league in terms of both the level of per capita income and its growth rate, but has to share the honours with Maharashtra and Haryana in that category. However, there is no evidence of any significant growth acceleration in Gujarat in the 2000s.

One could argue that it is easier to turn around a state that was at the bottom of the league like Bihar than to maintain, or to marginally improve, the performance of a state already at the top of the league, like Maharashtra, Haryana or Gujarat. After all, there is greater scope for improvement in the former case. Conversely, one could also argue that it is more challenging to turn around a backward state, because if it were easy, someone would have done it already. This is reinforced by the argument that Bihar is the third largest state, whereas Gujarat’s rank is 10th in terms of population, and it is difficult to achieve sharp improvements in a larger than a smaller state.

Be that as it may, many would argue that per capita income and its growth—the indices we have considered so far—are only partial measures of economic development. Among other things, these indices ignore aspects of development that are not captured in income, for example, life expectancy or education. Nor do these take into account income inequality or the extent of poverty. Therefore, we now turn our attention to the performance of the states in terms of the Human Development Index (HDI), level of inequality and the percentage of people below the poverty line.

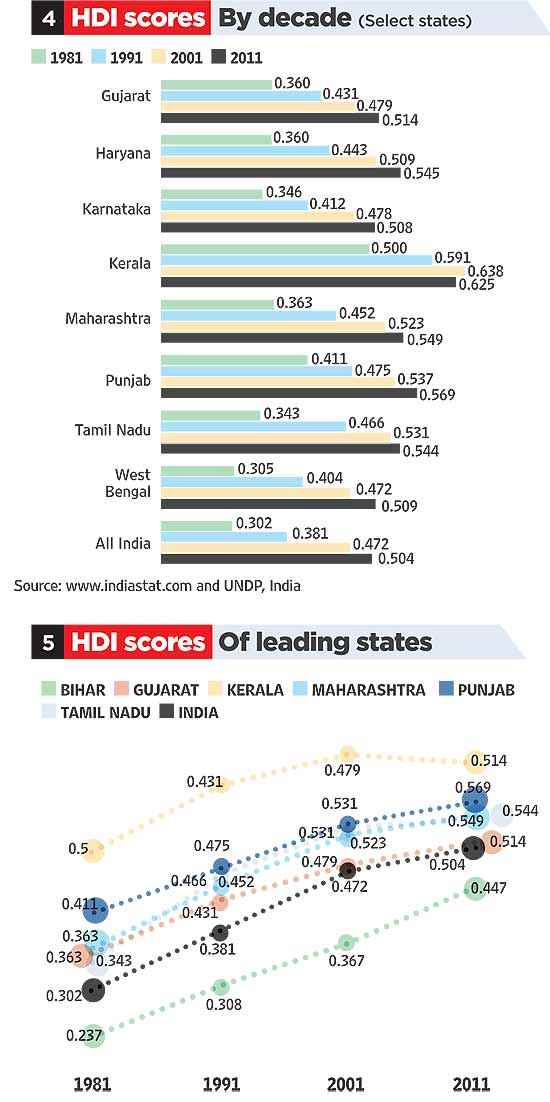

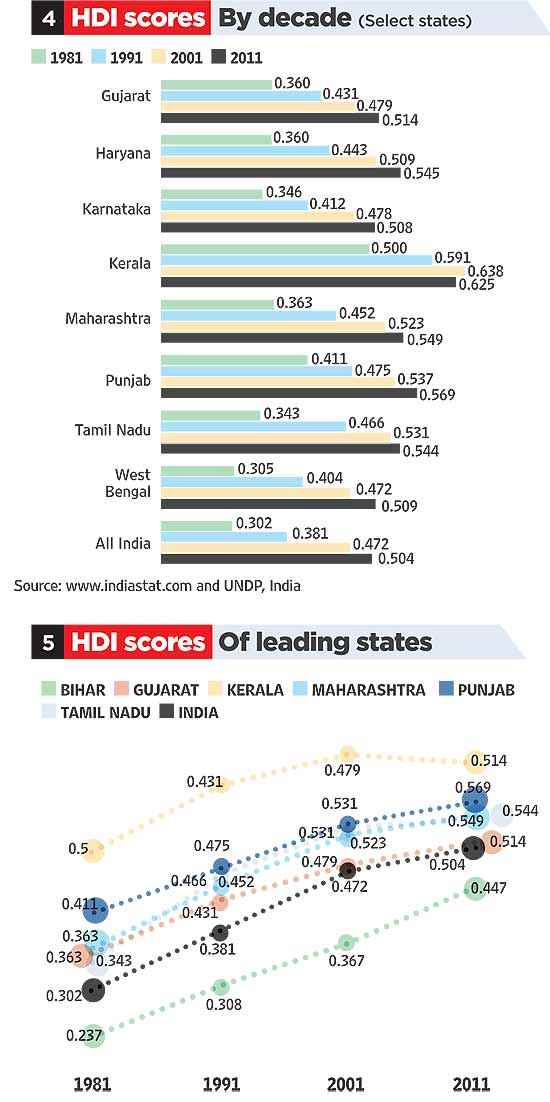

Table 4 highlights HDI scores of the seven states with HDI scores above the national average over the last three decades. These are Kerala, Punjab, Maharashtra, Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Karnataka. Table 5, on the other hand, plots the performance of some selected states with respect to the all-India average in terms of HDI. As we would expect, Kerala’s performance is literally off the charts. Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat, on the other hand, appear to have been going head to head. Their trends tell an interesting story. While Gujarat’s HDI performance was above the national average in the ’80s and ’90s, it decelerated in the 2000s and came down to the national average. In contrast, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, which started off at a similar level of HDI as Gujarat in the ’80s, have continued to perform better than the national average in the 2000s. Bihar, on the other hand, has consistently been below the national average, but it has made significant improvements over the last decade and shows signs of catching up to the national average.

Table 4 highlights HDI scores of the seven states with HDI scores above the national average over the last three decades. These are Kerala, Punjab, Maharashtra, Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Karnataka. Table 5, on the other hand, plots the performance of some selected states with respect to the all-India average in terms of HDI. As we would expect, Kerala’s performance is literally off the charts. Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat, on the other hand, appear to have been going head to head. Their trends tell an interesting story. While Gujarat’s HDI performance was above the national average in the ’80s and ’90s, it decelerated in the 2000s and came down to the national average. In contrast, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, which started off at a similar level of HDI as Gujarat in the ’80s, have continued to perform better than the national average in the 2000s. Bihar, on the other hand, has consistently been below the national average, but it has made significant improvements over the last decade and shows signs of catching up to the national average.

Thus, the HDI rankings of states present a different story than their rankings of per capita income levels or growth rates, with one exception. The only state that is in the top 3 in all the rankings so far is Maharashtra. Otherwise, the top prize for HDI goes to Kerala, and “the most improved in the 2000s” prize goes to Bihar.

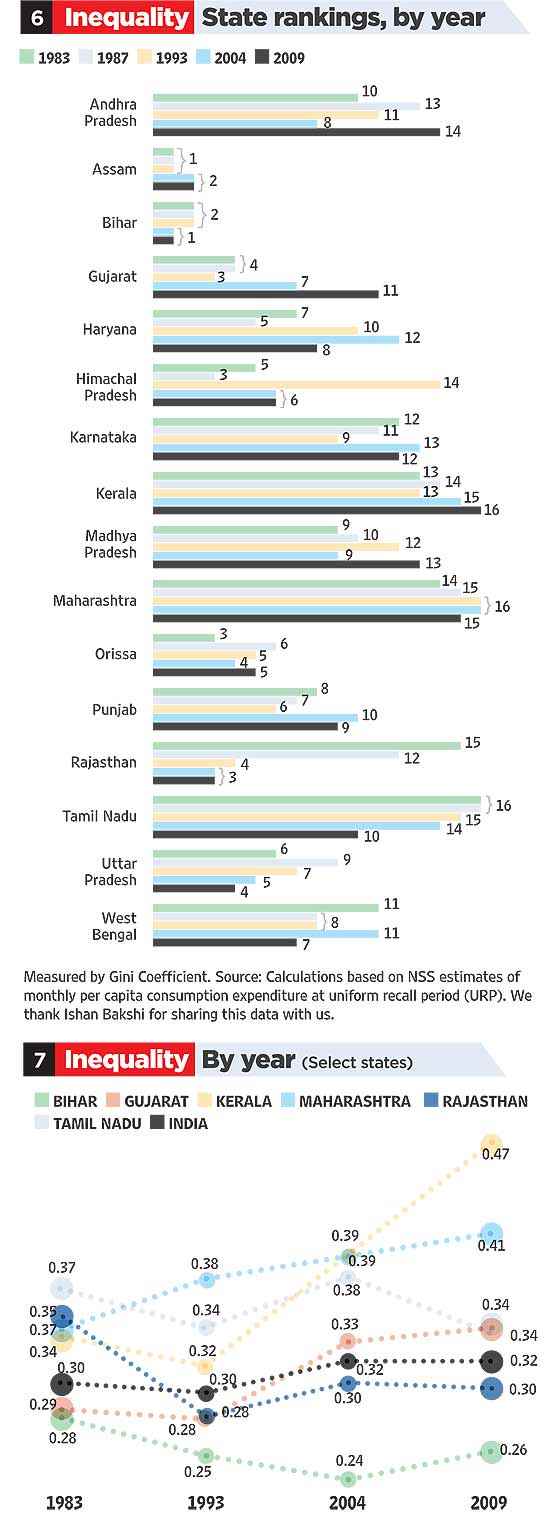

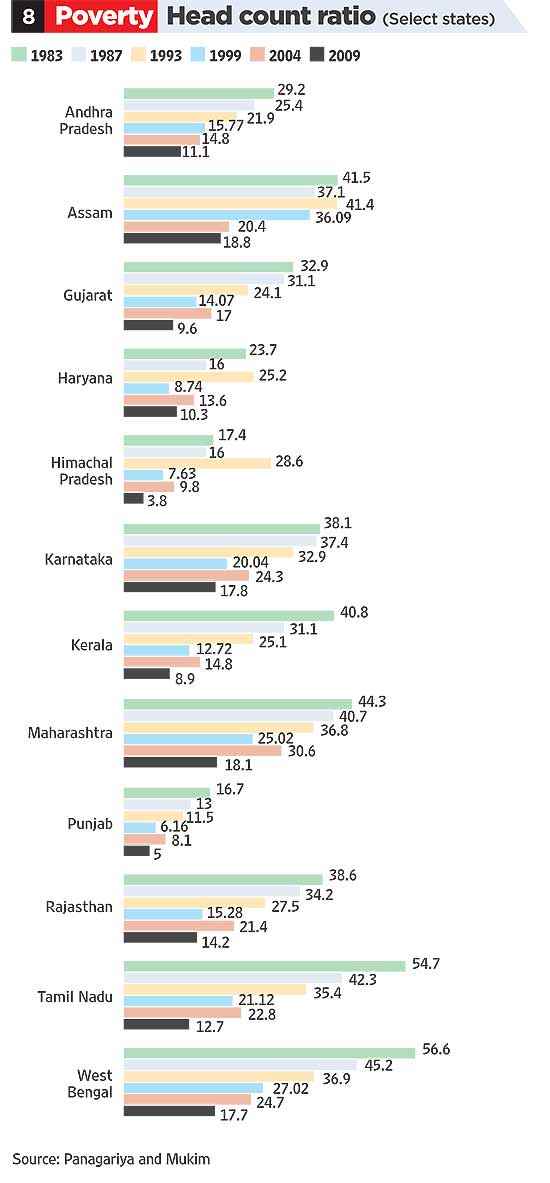

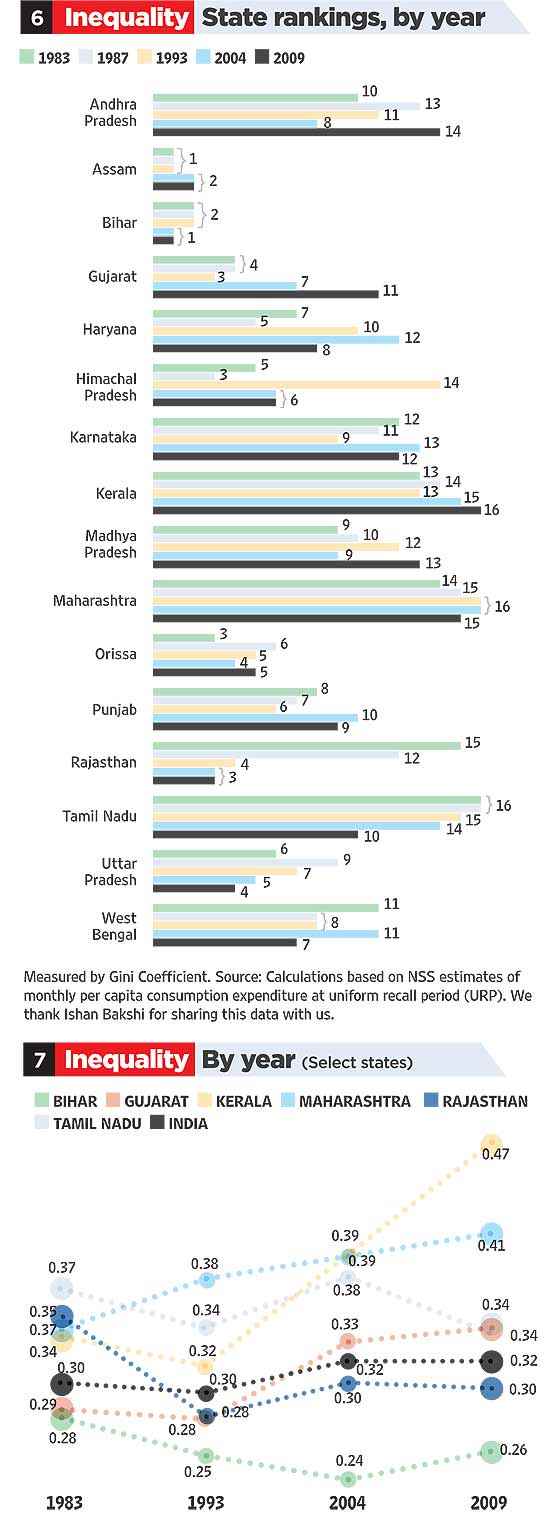

Next, we look at a few states’ ranking in terms of level of inequality (see Table 6) based on consumption expenditure. Assam and Bihar have consistently had the lowest levels of inequality according to this index. However, the state that really stands out, both in terms of relative ranking and absolute decline in inequality, is Rajasthan. Between the early ’80s and late 2000s, Rajasthan’s relative ranking improved from 15th to third, while its inequality measure fell by 14 per cent, the largest decline for any state. On the contrary, states that are leaders on the growth dimension are found to perform worse on inequality. For example, it’s evident from Table 7 that while inequality in Gujarat was lower than the national average in the ’80s and ’90s, it actually rose to levels above the national average in the 2000s. Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, too, have consistently recorded higher levels of inequality than the rest of India, with Kerala showing a sharp spike in the 2000s.

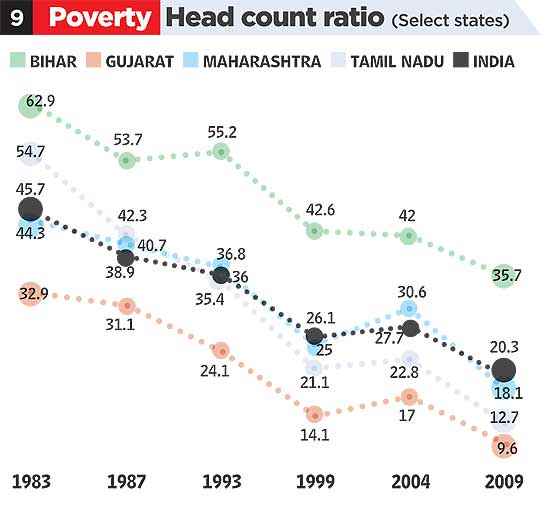

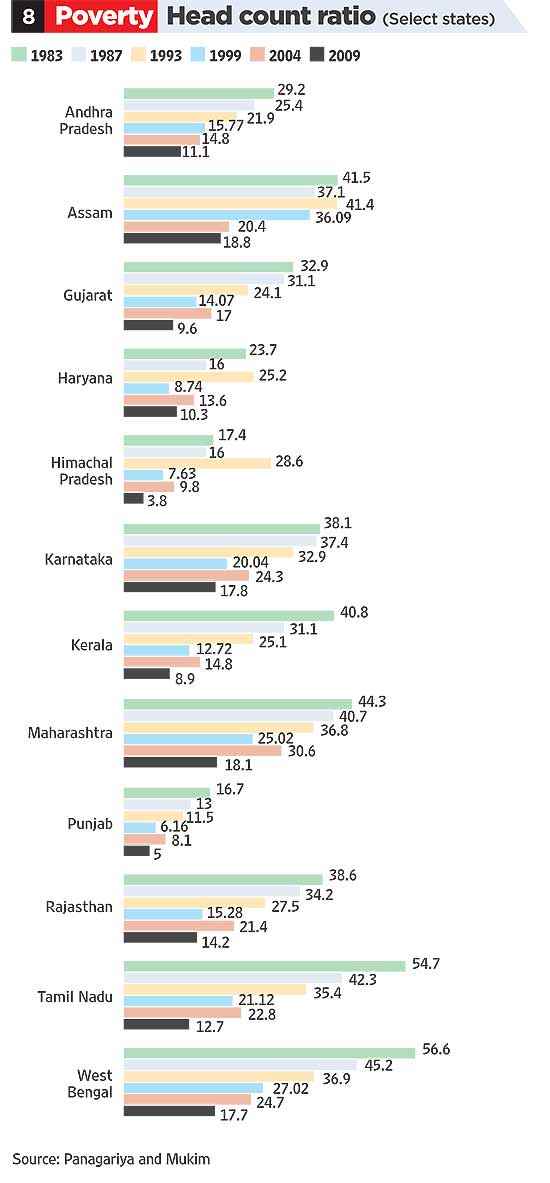

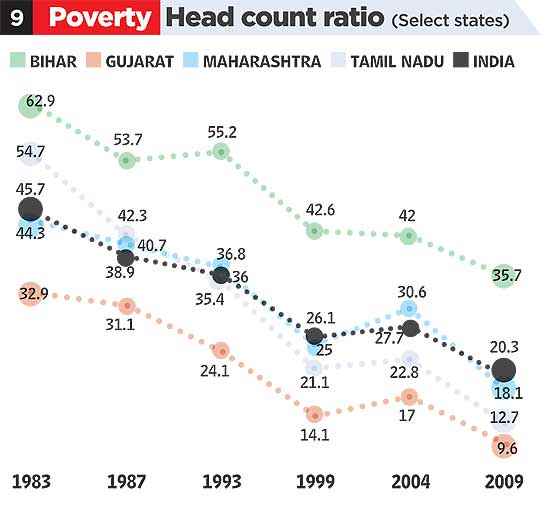

Lastly, we consider the percentage of population below the poverty line (see Table 8). We find that Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Kerala, Gujarat, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka have consistently had lower levels of poverty than the all-India average. Gujarat’s performance in poverty reduction over the years has been similar to that of Andhra Pradesh and Kerala. However, if we look at improvements in performance over the last decade, then Tamil Nadu is one of the top performers. Starting from a level of poverty that was higher than the national average in 1983, it ended up at a much lower level, similar to those of Gujarat, AP and Kerala, in 2009 (see Table 9). Bihar, although well above the national average in terms of poverty levels all through the three decades, has shown a sharp improvement over the last decade.

Is there, then, a clear answer to the question we had started with: did Gujarat truly outshine other states in the 2000s in terms of economic development? If we simply look at the figures, four facts will jump out: first, Bihar has improved the most in the 2000s, even though it has been at the bottom of the list for all indicators and still has a fair distance to go before it can go above the national average; second, Kerala has far outpaced other states in terms of HDI all through; third, Rajasthan was the star performer in terms of reducing inequality; and fourth, Maharashtra and Gujarat have consistently been top performers in terms of per capita income and its growth, with Haryana and Tamil Nadu deserving mention too. All these achievements are noteworthy but it is hard to single out any state as the top performer in the 2000s.

states in the 2000s in terms of economic development? If we simply look at the figures, four facts will jump out: first, Bihar has improved the most in the 2000s, even though it has been at the bottom of the list for all indicators and still has a fair distance to go before it can go above the national average; second, Kerala has far outpaced other states in terms of HDI all through; third, Rajasthan was the star performer in terms of reducing inequality; and fourth, Maharashtra and Gujarat have consistently been top performers in terms of per capita income and its growth, with Haryana and Tamil Nadu deserving mention too. All these achievements are noteworthy but it is hard to single out any state as the top performer in the 2000s.

To the extent this assessment goes against the view held by many people independent of their political leanings that Gujarat has done spectacularly well under Mr Modi, the explanation lies in our ‘differences in differences’ approach.

In particular, this is what we tried to figure out: did a state that has for a long time been one of the most developed states in terms of per capita income, and was already improving at a rate higher than the rest of the country, accelerate further and significantly increase its growth margin under Modi’s stewardship? Our analysis shows that this did not happen. Both Maharashtra and Gujarat improved upon an already impressive growth trajectory in the 2000s, but the margin of improvement was too small to be statistically meaningful. So while Gujarat’s overall record is undoubtedly very good all through the last three decades, its performance in the 2000s does not seem to justify the wild euphoria and exuberant optimism about Modi’s economic leadership.

Of course, it is possible that there are trends that this evidence cannot capture. Maybe with a longer time horizon, the effects of some of Modi’s policies will show up in the evidence, although given that he is now in his fourth consecutive term of power, this argument is not very strong. It is also possible that if Modi comes to power at the Centre, he may well achieve a turnaround of the Indian economy due to his governance style. All that is possible in theory, but the existing evidence is insufficient to support these views.

As John Maynard Keynes had famously said in the context of stockmarket bubbles, often our decisions to do something, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be “taken as the result of animal spirits”—a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction or rational calculation. In politics, too, maybe it is animal spirits that rule, not rational calculations based on statistical evidence. However, while election campaigns are run on slogans and sentiments, good governance depends on facts and figures. Bubbles eventually burst, waves of euphoria recede. At some point, the numbers need to add up.

A lot of this debate reflects disagreements about two sets of issues. First, there are many dimensions of economic performance—we could look at the level of per capita income, the growth rate of per capita income, human development indices (HDI) that put weight on not only income but also on non-income measures like education and health, the level of inequality, percentage of people below the poverty line, and many others. Which index we choose to emphasise reflects either our preferences as to the aspect of economic performance we value the most, or our views as to which dimension has to be improved (say, per capita income) for bettering the dimension we care about (say, poverty alleviation).

A lot of this debate reflects disagreements about two sets of issues. First, there are many dimensions of economic performance—we could look at the level of per capita income, the growth rate of per capita income, human development indices (HDI) that put weight on not only income but also on non-income measures like education and health, the level of inequality, percentage of people below the poverty line, and many others. Which index we choose to emphasise reflects either our preferences as to the aspect of economic performance we value the most, or our views as to which dimension has to be improved (say, per capita income) for bettering the dimension we care about (say, poverty alleviation).Secondly, even if we focus on one particular dimension of economic performance, how do we attribute changes in this dimension to the role of a specific leader? For example, how do we isolate the contribution of Narendra Modi and Nitish Kumar to the growth of Gujarat and Bihar, respectively, in the 2000s, especially as the country as a whole experienced a growth spurt in this period?

Therefore, the first issue is how to separate the leader’s contribution from other factors driving his or her state’s performance, for example, a general improvement in the economic environment of the country that benefits all states. The solution to this problem is to calculate the difference between the growth rate of the state for the years this leader was in power and the average growth rate of the rest of the states during the same period of time. If this difference is positive, then it is safe to say that the state under this leader grew faster than the rest of the country.

However, this is not enough. What if the state in question was always growing faster than the rest of the country? How can we then isolate the specific role of this leader?

To give an analogy, to show that a company’s performance under a new CEO has improved, it is not sufficient to show that the performance of the firm has been above average relative to that of other firms after the new CEO took over, as it is possible that this firm was already ahead of others. Similarly, if we find that a firm beat its past record under the new management, we cannot automatically attribute this to the CEO, as it is possible that all firms performed better in this period due to positive changes in the economic environment. To claim that this CEO had a transformative impact on the firm, we need to show not only that this firm stayed ahead of other firms after he took over but that its performance margin relative to other firms improved significantly under him.

Thus, returning to the example of Modi, in order to claim that his leadership had a significant impact on Gujarat’s economic performance, it is not enough to show that the state did better than the rest of India after he came to power in 2001. We have to demonstrate that the gap between Gujarat’s performance and that of the rest of India actually increased under his rule. This is a statistical method called ‘differences in differences’. It is routinely used to evaluate the performance of organisations under a particular management or the effectiveness of a particular government policy.

Turning to evidence, we look at the following key indices of economic performance—level of per capita income, its growth rate, HDI, inequality and the percentage of population below the poverty line—for the major Indian states. All through, we have focused on the major 16 states in terms of population. The larger a state, the harder it is to achieve improvements in per capita average economic indicators. Therefore, comparing a large state like Uttar Pradesh and a small one like Nagaland can be misleading; it is better to compare like with like. However, we have to keep in mind that even among the major states, turning around a state with a larger population is a harder task.

We begin by looking at the most obvious economic indicator—the level of per capita income. In terms of average per capita income ranking of states over the 1980s, ’90s and 2000s, the top three states are Haryana, Punjab and Maharashtra (see Table 1). Gujarat’s average rank is 4. On the other hand, Bihar, which has been in the news lately due to its spectacular turnaround over the recent years under the leadership of Nitish Kumar, has been consistently at the bottom of this league with a rank of 16, below UP, which too has remained steady at number 15.

In terms of improving their relative ranking over the three decades, the top performers among the leading states are Maharashtra, Gujarat, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Between the ’80s and now, Maharashtra has moved from 3 to 1, Gujarat from 4 to 3, Kerala from 10 to 5 and Tamil Nadu from 7 to 4. Interestingly, the rise in the ranks of these four has been accompanied by the relative decline of Punjab, which went from being the very top state in the ’80s and ’90s to No. 7 in 2010. This suggests that, as in athletic races, the relative rank of a state may go up or down either due to a change in its own performance or due to a change in the rival’s performance.

Thus, to obtain a fuller picture of the economic performance of these states, we also need to consider their relative growth performances. The relative ranking at a given point of time as in Table 1 gives only a snapshot of where states stand in terms of economic performance. But as we know from athletic races, unless that point happens to be the finishing line, it is the rate at which an athlete is accelerating that determines the final outcome. While there is no final finishing line in the race of economic development, the current growth performance of a state can give an indication of its potential position in the future. Is the rise in rankings of states like Maharashtra and Gujarat also matched by a faster growth rate on their part? Also, are there states that are lower down in the ranking but are growing faster than average and so can hope to improve their ranking in the future?

Table 2 documents the annual average growth rates of states which have performed better than national average (leaders) in each of the three decades. Only three states have had above average growth performance in all three decades: Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. They were joined by Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Haryana and Kerala in the 2000s.

Interestingly, the growth rate of Punjab, initially one of the top-ranked states in terms of per capita income level, has been below the national average in the last two decades. Thus it is not surprising that it is slipping down in rank below other faster-growing states. Bihar, on the other hand, is poised to rise up the ranks with a higher than average growth rate of per capita income in the 2000s. In a way, Bihar’s story is the opposite of Punjab’s: while it is still at the bottom of the chart in terms of the level of per capita income, it can expect to improve its rank if it maintains its recent high growth rate.

Now we come to one of the key questions. Which are the states that improved their performance in the 2000s both with respect to their past performance in the earlier two decades, and with respect to the performance of other states in the 2000s? Table 3 graphically plots the average annual growth rates of five states against the national average over time. This graph shows an interesting trend: while Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra have been going neck and neck (and Haryana, which is not shown in the figure), and as already mentioned, have consistently performed above the national average, none of them has experienced a huge acceleration in growth rate in the 2000s. In contrast, Bihar, which was consistently doing worse than the national average through the ’80s and ’90s, shot up above the national average in the 2000s, converging to rates achieved by established leaders like Gujarat, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu.

To sum up, we see that Maharashtra, Haryana, Punjab, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu have been among the richest states in the last three decades. In the 2000s, the big news was Punjab dropping from the top 5 and Kerala breaking into this select group. Among the rest, Maharashtra ended as the topper in the latter half of the 2000s, and Gujarat at a very respectable number 3, after Haryana. In terms of growth performance, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra were the toppers over the last three decades but in the 2000s, three other states raised their game to join the list of fastest-growing states: Bihar, Haryana and Andhra Pradesh. However, if any state could claim that its performance relative to the rest of India actually improved in the 2000s, that state is Bihar.

Therefore, if awards must be given, Bihar deserves the prize for the most dramatic turnaround in the 2000s. Gujarat gets credit for having steadily been on top of the league in terms of both the level of per capita income and its growth rate, but has to share the honours with Maharashtra and Haryana in that category. However, there is no evidence of any significant growth acceleration in Gujarat in the 2000s.

One could argue that it is easier to turn around a state that was at the bottom of the league like Bihar than to maintain, or to marginally improve, the performance of a state already at the top of the league, like Maharashtra, Haryana or Gujarat. After all, there is greater scope for improvement in the former case. Conversely, one could also argue that it is more challenging to turn around a backward state, because if it were easy, someone would have done it already. This is reinforced by the argument that Bihar is the third largest state, whereas Gujarat’s rank is 10th in terms of population, and it is difficult to achieve sharp improvements in a larger than a smaller state.

Be that as it may, many would argue that per capita income and its growth—the indices we have considered so far—are only partial measures of economic development. Among other things, these indices ignore aspects of development that are not captured in income, for example, life expectancy or education. Nor do these take into account income inequality or the extent of poverty. Therefore, we now turn our attention to the performance of the states in terms of the Human Development Index (HDI), level of inequality and the percentage of people below the poverty line.

Table 4 highlights HDI scores of the seven states with HDI scores above the national average over the last three decades. These are Kerala, Punjab, Maharashtra, Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Karnataka. Table 5, on the other hand, plots the performance of some selected states with respect to the all-India average in terms of HDI. As we would expect, Kerala’s performance is literally off the charts. Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat, on the other hand, appear to have been going head to head. Their trends tell an interesting story. While Gujarat’s HDI performance was above the national average in the ’80s and ’90s, it decelerated in the 2000s and came down to the national average. In contrast, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, which started off at a similar level of HDI as Gujarat in the ’80s, have continued to perform better than the national average in the 2000s. Bihar, on the other hand, has consistently been below the national average, but it has made significant improvements over the last decade and shows signs of catching up to the national average.

Table 4 highlights HDI scores of the seven states with HDI scores above the national average over the last three decades. These are Kerala, Punjab, Maharashtra, Haryana, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Karnataka. Table 5, on the other hand, plots the performance of some selected states with respect to the all-India average in terms of HDI. As we would expect, Kerala’s performance is literally off the charts. Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat, on the other hand, appear to have been going head to head. Their trends tell an interesting story. While Gujarat’s HDI performance was above the national average in the ’80s and ’90s, it decelerated in the 2000s and came down to the national average. In contrast, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, which started off at a similar level of HDI as Gujarat in the ’80s, have continued to perform better than the national average in the 2000s. Bihar, on the other hand, has consistently been below the national average, but it has made significant improvements over the last decade and shows signs of catching up to the national average.Thus, the HDI rankings of states present a different story than their rankings of per capita income levels or growth rates, with one exception. The only state that is in the top 3 in all the rankings so far is Maharashtra. Otherwise, the top prize for HDI goes to Kerala, and “the most improved in the 2000s” prize goes to Bihar.

Next, we look at a few states’ ranking in terms of level of inequality (see Table 6) based on consumption expenditure. Assam and Bihar have consistently had the lowest levels of inequality according to this index. However, the state that really stands out, both in terms of relative ranking and absolute decline in inequality, is Rajasthan. Between the early ’80s and late 2000s, Rajasthan’s relative ranking improved from 15th to third, while its inequality measure fell by 14 per cent, the largest decline for any state. On the contrary, states that are leaders on the growth dimension are found to perform worse on inequality. For example, it’s evident from Table 7 that while inequality in Gujarat was lower than the national average in the ’80s and ’90s, it actually rose to levels above the national average in the 2000s. Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu and Kerala, too, have consistently recorded higher levels of inequality than the rest of India, with Kerala showing a sharp spike in the 2000s.

Lastly, we consider the percentage of population below the poverty line (see Table 8). We find that Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Kerala, Gujarat, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka have consistently had lower levels of poverty than the all-India average. Gujarat’s performance in poverty reduction over the years has been similar to that of Andhra Pradesh and Kerala. However, if we look at improvements in performance over the last decade, then Tamil Nadu is one of the top performers. Starting from a level of poverty that was higher than the national average in 1983, it ended up at a much lower level, similar to those of Gujarat, AP and Kerala, in 2009 (see Table 9). Bihar, although well above the national average in terms of poverty levels all through the three decades, has shown a sharp improvement over the last decade.

Is there, then, a clear answer to the question we had started with: did Gujarat truly outshine other

states in the 2000s in terms of economic development? If we simply look at the figures, four facts will jump out: first, Bihar has improved the most in the 2000s, even though it has been at the bottom of the list for all indicators and still has a fair distance to go before it can go above the national average; second, Kerala has far outpaced other states in terms of HDI all through; third, Rajasthan was the star performer in terms of reducing inequality; and fourth, Maharashtra and Gujarat have consistently been top performers in terms of per capita income and its growth, with Haryana and Tamil Nadu deserving mention too. All these achievements are noteworthy but it is hard to single out any state as the top performer in the 2000s.

states in the 2000s in terms of economic development? If we simply look at the figures, four facts will jump out: first, Bihar has improved the most in the 2000s, even though it has been at the bottom of the list for all indicators and still has a fair distance to go before it can go above the national average; second, Kerala has far outpaced other states in terms of HDI all through; third, Rajasthan was the star performer in terms of reducing inequality; and fourth, Maharashtra and Gujarat have consistently been top performers in terms of per capita income and its growth, with Haryana and Tamil Nadu deserving mention too. All these achievements are noteworthy but it is hard to single out any state as the top performer in the 2000s.To the extent this assessment goes against the view held by many people independent of their political leanings that Gujarat has done spectacularly well under Mr Modi, the explanation lies in our ‘differences in differences’ approach.

In particular, this is what we tried to figure out: did a state that has for a long time been one of the most developed states in terms of per capita income, and was already improving at a rate higher than the rest of the country, accelerate further and significantly increase its growth margin under Modi’s stewardship? Our analysis shows that this did not happen. Both Maharashtra and Gujarat improved upon an already impressive growth trajectory in the 2000s, but the margin of improvement was too small to be statistically meaningful. So while Gujarat’s overall record is undoubtedly very good all through the last three decades, its performance in the 2000s does not seem to justify the wild euphoria and exuberant optimism about Modi’s economic leadership.

Of course, it is possible that there are trends that this evidence cannot capture. Maybe with a longer time horizon, the effects of some of Modi’s policies will show up in the evidence, although given that he is now in his fourth consecutive term of power, this argument is not very strong. It is also possible that if Modi comes to power at the Centre, he may well achieve a turnaround of the Indian economy due to his governance style. All that is possible in theory, but the existing evidence is insufficient to support these views.

As John Maynard Keynes had famously said in the context of stockmarket bubbles, often our decisions to do something, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be “taken as the result of animal spirits”—a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction or rational calculation. In politics, too, maybe it is animal spirits that rule, not rational calculations based on statistical evidence. However, while election campaigns are run on slogans and sentiments, good governance depends on facts and figures. Bubbles eventually burst, waves of euphoria recede. At some point, the numbers need to add up.

By Maitreesh Ghatak and Sanchari Roy

(Maitreesh Ghatak is Professor of Economics at the London School of Economics; Sanchari Roy is a research associate at the Department of Economics, University of Warwick, UK.)