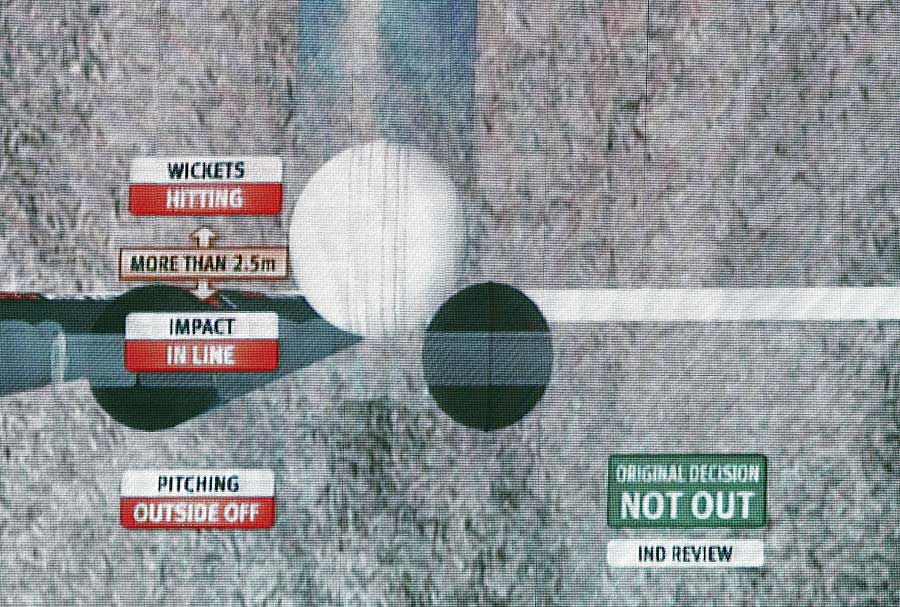

At its annual general meeting in July, the ICC decided to reduce the margin of the umpire's-call element in the Decision Review System. The old rule required that at least 50% of the ball must be hitting at least 50% of a stump in the estimate provided by the ball-tracking model. The change, which comes into effect this month, now requires at least 50% of the ball to be hitting any part of a stump, or, as the ICC phrased it: "The size of the zone inside which half the ball needs to hit for a Not Out decision to be reversed to Out will increase, changing to a zone bordered by the outside of off and leg stumps, and the bottom of the bails (formerly the centre of off and leg stumps, and the bottom of the bails)."

The umpire's call has traditionally invited the scorn of a number of prominent players as well as commentators. The rule change is a victory for the view that umpire's call is excessively deferential to the umpire. In this essay, which extends ideas I have written about previously, I consider what this change says about the past, present and future of umpiring.

****

Contradictions abound with the DRS. It was invented, according to the ICC, to correct obvious umpiring mistakes. But it is used most frequently to litigate on marginal umpiring decisions. The purpose of the player review was to allow players to question umpiring decisions where they knew the umpires had got it wrong. Yet players routinely use the review speculatively, to see if they can get a marginal reversal. The DRS was invented because umpires were deemed to be experts who made clear (or obvious) mistakes from time to time. It was not intended to make up for any perceived shortcoming in an umpire's expertise. It was intended to make up for the human tendency to make mistakes in real time. This distinction is important.

If an umpire lacked expertise, then no matter how many times he or she saw a particular lbw appeal, the right decision would not be reliably reached. But if an umpire simply made a mistake in real time, it would be recognised on replay. As an analogy, think of the times where you have made a mistake adding up two numbers. This is a mistake. It does not occur because you don't know the correct way to add two numbers. If you didn't know how to add, no matter how many times you looked at the problem, you wouldn't know how to reliably calculate the correct answer.

The DRS was not intended to make up for any perceived shortcoming in an umpire's expertise

Not only is the DRS only rarely used for this kind of correction, the process used to identify mistakes - the player review - fails about 75% of the time. At the 2015 World Cup, 583 umpiring decisions were made (including 312 lbw and 229 catches): an umpiring decision is made any time an umpire answers an appeal, so not all dismissals involve umpiring decisions and nor do all umpiring decisions result in dismissals. Eighty-four were reviewed and only 20 of those were successful; 57 reviews were for lbw appeals, of which only eight were successful. According to data provided by the ICC, in all international cricket between April 2013 and March 2016 in which the DRS was used, one in six umpiring decisions was reviewed by players. Three out of four player reviews failed. Umpiring decisions on lbw appeals were reviewed more frequently - about one in every four. Four out of five such reviews were unsuccessful.

Many players, as well as TV commentators, often betray a misunderstanding about the DRS, beginning with the basic question of what it is. In cricket the umpire can choose between two options when answering an appeal - out and not out. The DRS is a system for reviewing the umpire's answer. It is not a system for providing a new answer to the original appeal by setting aside the umpire's first answer.

The DRS is also frequently the catch-all term for the suite of technologies used within the review system, technologies that are also not well understood. The most widespread misunderstanding is about ball-tracking and the notion that the estimate of the path of the ball from pad to stumps is not an estimate but a statement of fact. This is particularly puzzling, since it suggests that players and commentators misunderstand the lbw law. A leg-before decision is built on the umpire hypothesising about an event that never occurs, that never occurred and never will occur.

----Also read

Abolish the LBW - it has no place in the modern world

----

The rise of the DRS is tied in to the way the authority of the umpires has been undermined by players and broadcasters over the years Cameron Spencer / © Getty Images

Yet, even Kumar Sangakkara evidently misses this point. Perhaps he was caught up in the disappointment of the moment - his former team-mates had just been denied an lbw thanks to a review by the England batsman when he tweeted: "High time the ICC got rid of this umpires [sic] call. If the ball is hitting the stumps it should be out on review regardless of umps decision." Later he added: "is a feather of a nick marginal if it doesn't show up on hotspot but only on snicko? Then why use technology." Sangakkara is not alone in misunderstanding that when an lbw review returns umpire's call, the ball-tracking estimate is telling us: "This may go on to hit the stumps, but it cannot be said with sufficient certainty."

Now it is true that what the ball-tracking companies consider to be sufficient certainty and what the ICC considers to be so is not the same thing. Different providers use different methods for predicting the ball's path. They are also not equally confident about the reliability of the predictions. Ian Taylor, the head of Virtual Eye, has previously suggested that TV umpires be given an override switch that allows them to ignore the ball-tracking estimate in certain circumstances. Paul Hawkins, of Hawk-Eye Innovations, is far more confident of his company's ball-tracking predictions.

But if we take the criticisms of Sangakkara, and Shane Warne and Ian Botham among others, to their logical conclusion, then by eliminating the umpire's call, and with it the idea of the marginal decision itself, there is no longer any need for the umpire. If the review is for the appeal and not the decision, then why is the decision necessary in the first place? Why make umpires stand in the sun for six hours if their expert judgement, from the best position in the house, is not needed?

Why not use only DRS technologies instead of an umpire? Almost every single thing the umpire does on the field can now be done from beyond the boundary. The umpires could sit in a nice air-conditioned office in the pavilion with a dazzling array of screens and controls. They could even operate the electronic scoreboard from there, instead of signalling boundaries and extras to the scorers.

A leg-before decision is built on the umpire hypothesising about an event that never occurs, that never occurred and never will occur

One practical answer is that these technologies are expensive. We will still need umpires at the lower levels. But without the incentive of being able to become an international umpire, what might happen to the quality of umpiring at the lower levels?

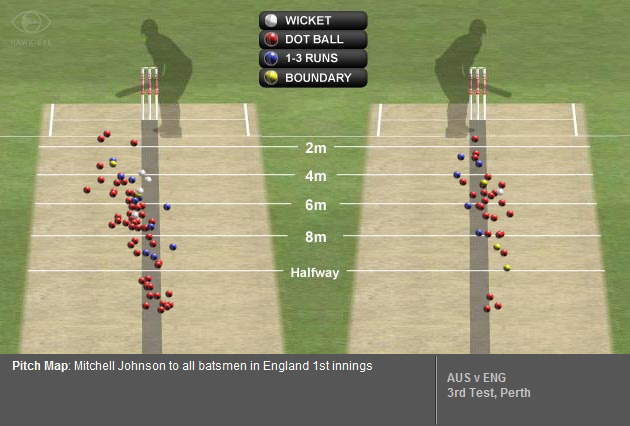

As a scientific matter, if one is to consider replacing the umpire with such technologies then the responsible thing to do is to consider two kinds of error. First is the margin of error of the technology itself. Take the ball-tracker. The amount of information available for each delivery is not exactly the same. For instance, the faster the delivery, the fewer the number of frames of video available from which the path of the ball can be traced. And because the same amount of data is not available for each delivery, all projected paths cannot be predicted with equal certainty.

This is not to say that most paths cannot be predicted with sufficiently little uncertainty. In an interview in 2011, Hawkins explained that the accuracy of the prediction is more binary than one might imagine. There is either sufficient data for a reliable prediction or there isn't. One example of a situation where there isn't sufficient data is for yorkers. The ball-tracking system designates any situation in which the distance between the ball's pitching point and the point of impact is less than 40cm to be an "extreme" lbw. A mistake by the ball-tracking system in an lbw review involving Shan Masood about two years ago may have been due to this condition.

Before ball-tracking, the decision against Masood could have been argued two ways - one, that the ball was very likely to miss leg stump, and the other, that Masood had moved a long way across and was hit on the back heel inside the crease. The ball did not have much to travel. This would have introduced doubt into the idea that the ball would have missed the stumps.

If we eliminate the idea of umpire's call, and with it the idea of the marginal decision itself, is there a need for the umpire?Richard Heathcote / © Getty Images

In the ball-tracking era, with the increased number of mini-decisions in the chain between the original appeal and the final decision, there are more points where people can make mistakes than before. What's more, there are more people who can make mistakes. The Masood lbw did involve operator error according to Hawk-Eye. The upshot of all this is that the cricketing question of whether or not the decision against Masood was reasonably defensible was set aside in favour of doubts about the plausibility of the ball-tracking estimate.

Hawk-Eye did once suggest visualising the confidence of each prediction by drawing an "uncertainty ellipse" around the ball. In cases where there was sufficient information to make the prediction, the ellipse showing a calculated error would be extremely close to the ball. Showing the ellipse, however minor the error might be, would continually remind viewers of two facts: first, that the animation they were watching was an estimate, and second, that the estimate was probabilistic. This was rejected by broadcasters, who preferred a "definitive" visualisation.

I am inclined to accept that the mathematical prediction models are generally reliable. As more testing is carried out, and with advances in hardware, these models will continue to improve. But even if we assume that the model is good, and its least confident prediction is still sufficiently confident, we also have to make allowances for shortcomings - those factors it is not designed to account for. I am not referring to atmospherics, or the peculiar traits of a cricket ball at different stages of its existence (the model's solution of tracking movement has an elegant way of accounting for these). Instead I refer to, for instance, the limits of video - the path of the ball from the bowler's hand to the batsman is constructed using multiple video frames from multiple tracking cameras; or the non-standard nature of cricket stadiums, which could introduce limits to the extent of calibration possible; or the difference in the quality of video available in different countries.

Every city in the world that requires the certification of building designs before construction requires that concrete structures be "over-designed" to include a factor of safety. This is usually a matter, for example, of increasing the calculated beam depth for a given span by a certain percentage. This is done to cover for uncertainties that the calculation cannot take into account. The umpire's call is similar.

****

Connoisseurs and administrators have dreamed of using technology to help umpires for decades. But the development of the DRS is not solely the result of an innocent, abstract desire to help umpiring. Its evolution is a direct consequence of the authority of the umpire being undermined by players, aided and abetted by broadcasters. It was not inevitable that technical assistance for umpiring decisions should take the form of a review initiated by players. Nor was it inevitable that the very technologies used to enhance the entertainment value of the television broadcast should become tools of adjudication.

Hawk-Eye did once suggest visualising the confidence of each prediction by drawing an "uncertainty ellipse" around the ball. In cases where there was sufficient information to make the prediction, the ellipse showing a calculated error would be extremely close to the ball. Showing the ellipse, however minor the error might be, would continually remind viewers of two facts: first, that the animation they were watching was an estimate, and second, that the estimate was probabilistic. This was rejected by broadcasters, who preferred a "definitive" visualisation.

I am inclined to accept that the mathematical prediction models are generally reliable. As more testing is carried out, and with advances in hardware, these models will continue to improve. But even if we assume that the model is good, and its least confident prediction is still sufficiently confident, we also have to make allowances for shortcomings - those factors it is not designed to account for. I am not referring to atmospherics, or the peculiar traits of a cricket ball at different stages of its existence (the model's solution of tracking movement has an elegant way of accounting for these). Instead I refer to, for instance, the limits of video - the path of the ball from the bowler's hand to the batsman is constructed using multiple video frames from multiple tracking cameras; or the non-standard nature of cricket stadiums, which could introduce limits to the extent of calibration possible; or the difference in the quality of video available in different countries.

Every city in the world that requires the certification of building designs before construction requires that concrete structures be "over-designed" to include a factor of safety. This is usually a matter, for example, of increasing the calculated beam depth for a given span by a certain percentage. This is done to cover for uncertainties that the calculation cannot take into account. The umpire's call is similar.

****

Connoisseurs and administrators have dreamed of using technology to help umpires for decades. But the development of the DRS is not solely the result of an innocent, abstract desire to help umpiring. Its evolution is a direct consequence of the authority of the umpire being undermined by players, aided and abetted by broadcasters. It was not inevitable that technical assistance for umpiring decisions should take the form of a review initiated by players. Nor was it inevitable that the very technologies used to enhance the entertainment value of the television broadcast should become tools of adjudication.

Umpires are right to be fearful. Their authority has been systematically dismantled from the commentary box

The very design of the DRS betrays its impulses. If the point of the system were to correct obvious mistakes, why would such sophisticated technologies be necessary? Shouldn't an obvious error, by its definition, be obvious? Instead, it appears that a central impulse was to ensure that the very technologies that were used by broadcasters to litigate umpiring decisions be used in the review. Given the pressure the umpires had been placed under, it would not have been viable to use a system of reviewing decisions that did not include these technologies.

Consider now examples of the oldest form of review - requesting replays for run-out calls - to see how umpires have begun to question their own expertise. Matters have reached a stage where they reflexively draw a TV screen in the air even for the politest, mildest appeals, where it is patently clear the batsman is in. The replay often shows him well inside the crease, or even past the stumps. There are arguments to be made for being safe rather than sorry, but there are instances when umpires signal for the replay even as the batsman is walking off to the pavilion. This is motivated by fear, not caution.

And umpires are right to be fearful. Their authority has been systematically dismantled from the commentary box. To see why, we must understand the model of the TV "argument", the central feature of which is balance, not accuracy or depth or nuance (which lead to complexity, which is boring for TV).

If one person takes the position that the earth is flat, and the other that the earth is round, then a "balanced" argument treats both positions to be equally valid. Here's how it might happen during commentary. An important batsman is given not out at a crucial stage. One commentator makes an effort to explain why the decision was marginal and why it might have reasonably gone either way, that the umpire did not make a mistake. The co-commentator, either by way of "balance", or in an attempt to live up to a TV persona, responds by saying he thought it was out and the fact that it was not given is a mistake. One side concludes the earth is round. The other disagrees. If there is time, they have a "debate", which usually amounts to the two claims being restated in different ways until time runs out.

The "balanced" argument comes with the following corollary in cricket commentary - as long as an umpire is praised for getting a decision right, it is perfectly reasonable to excoriate him for getting a decision wrong. The rightness and wrongness of marginal decisions is, by definition, doubtful. But the manufactured certainty of a visualisation like the ball-tracker enables a thorough excoriation, minimising marginality. One commentator will offer the careful, nuanced live commentary. The other will see the ball-tracker depicting the ball clipping leg stump and say, "This is where umpire's call saves the batsman despite a bad original decision." Of course, if the ball-tracker shows the ball missing by a whisker, the same commentator will praise the original decision. The difference between the two stances is often no more than a fraction of an inch. There is no cricketing merit in having such divergent opinions about instances separated by fractions of an inch, but it makes for great TV; never mind that it undermines the authority of the umpire.

Under the DRS not only are there more points where people can make mistakes than before, there are more people involved in the process, who can make mistakes © Getty Images

Too many commentators seem willing to accept the idea that a decision is worth reviewing just because a player does not like it. If not, the vast number of bad player reviews would bother them at least as much as the marginal lbw decision going against their team seems to. They don't. You never hear of how consistently unsuccessful players are at reviews. That's one statistic commentators rarely track.

Their job precludes them from saying "It could reasonably have gone either way" too often. That response makes everybody but the most serious cricket fans deeply unhappy. And if only serious cricket fans watched cricket, elementary economics says that it would not interest most broadcasters. The point is not that commentators are inherently bad. That matters are not as simple as this is palpably evident from the fact that the same commentators sound different depending on the broadcaster they work for. Rather, the point is that the DRS is the product of the complex interplay of cricket and the lucrative show business of its broadcast. Commentators constitute the high-profile face of the show-business side and usually have a deep history on the cricketing side, and hence are central characters.

As conclusion, here is an idiosyncratic history of umpiring, told through three umpiring decisions and their presentation. It constitutes a prehistory of this latest change in the rules. On the fourth evening at Adelaide Oval on a day late in 1999, Sachin Tendulkar was given out lbw after ducking into a Glenn McGrath bouncer. The ball didn't rise on a wearing, pre-drop-in-era wicket. Ian Chappell and Sunil Gavaskar were on commentary, and after describing the action, Chappell said:

"Dangerous lbw decision for an umpire to give because there are so many moving parts. It's not like the batsman being hit on the pad. There's a lot of movement when the batsman's ducking like that. It's hit him up under the back of the arm. [Pauses as the ball leaves McGrath's hand and reaches Tendulkar] Oh, it's not the easiest decision to give at all. Because with all those things moving, you've got to be very sure."

Gavaskar was interested in why Tendulkar chose to duck. He pointed out that the short leg probably worried Tendulkar and made him choose not to play at the ball. Chappell and Gavaskar had been discussing, even before the appeal, how ducking was likely to be risky given the uneven bounce. There was no Hawk-Eye. But between the video and the commentary, it was clear to the viewer what had occurred. Australia had set a trap and it had worked. The decision McGrath won was bold but reasonable. It was possible to reasonably disagree with Daryl Harper, but it could not be successfully argued that he was definitely wrong.

Their job precludes them from saying "It could reasonably have gone either way" too often. That response makes everybody but the most serious cricket fans deeply unhappy. And if only serious cricket fans watched cricket, elementary economics says that it would not interest most broadcasters. The point is not that commentators are inherently bad. That matters are not as simple as this is palpably evident from the fact that the same commentators sound different depending on the broadcaster they work for. Rather, the point is that the DRS is the product of the complex interplay of cricket and the lucrative show business of its broadcast. Commentators constitute the high-profile face of the show-business side and usually have a deep history on the cricketing side, and hence are central characters.

As conclusion, here is an idiosyncratic history of umpiring, told through three umpiring decisions and their presentation. It constitutes a prehistory of this latest change in the rules. On the fourth evening at Adelaide Oval on a day late in 1999, Sachin Tendulkar was given out lbw after ducking into a Glenn McGrath bouncer. The ball didn't rise on a wearing, pre-drop-in-era wicket. Ian Chappell and Sunil Gavaskar were on commentary, and after describing the action, Chappell said:

"Dangerous lbw decision for an umpire to give because there are so many moving parts. It's not like the batsman being hit on the pad. There's a lot of movement when the batsman's ducking like that. It's hit him up under the back of the arm. [Pauses as the ball leaves McGrath's hand and reaches Tendulkar] Oh, it's not the easiest decision to give at all. Because with all those things moving, you've got to be very sure."

Gavaskar was interested in why Tendulkar chose to duck. He pointed out that the short leg probably worried Tendulkar and made him choose not to play at the ball. Chappell and Gavaskar had been discussing, even before the appeal, how ducking was likely to be risky given the uneven bounce. There was no Hawk-Eye. But between the video and the commentary, it was clear to the viewer what had occurred. Australia had set a trap and it had worked. The decision McGrath won was bold but reasonable. It was possible to reasonably disagree with Daryl Harper, but it could not be successfully argued that he was definitely wrong.

Too many commentators seem willing to accept the idea that a decision is worth reviewing just because a player does not like it

Nearly 12 years later in Mohali, Tendulkar against Pakistan in a World Cup semi-final. In the 11th over of India's innings, Saeed Ajmal got a ball to grip and turn past Tendulkar's forward defensive. On commentary, even as Ajmal and Kamran Akmal were seized by the appeal of their cricketing lives, Sourav Ganguly's instinctive reaction was that it looked very close. Sure enough, umpire Ian Gould gave it out.

It was a perfectly reasonable decision. Any umpire who made the same decision could not be faulted. But here was a wrinkle. The ball-tracking estimate showed that the ball would have missed leg stump by what seemed to be a few angstroms. This time the intimately intertwined apparatus constituted by the umpires and the broadcast told us simply that Gould was wrong and Tendulkar was safe. Leg-before decisions were no longer reasonable judgements by human beings. Ganguly's instinctive reaction on commentary was lost amid the manufactured certainty. Cricket's broadcast no longer had time for the subtle idea that close appeals are close because they are close to being out, while close decisions are close because they are more or less equally close to being out and not out.

Four years later, during the knockout stages of the 2015 World Cup, we, the viewers, were finally allowed into the inner sanctum. While a review was in progress, instead of hearing commentators, we heard what the umpires said to each other.

"Let's look at the no-ball. Yes, that looks fine."

"May I see spin-vision when you are ready?"

"Let's see the ball-tracker when you are ready."

"Pitched outside leg."

The ICC's rulebook governing the DRS prescribed these questions. The role umpires were playing could have been played just as well if they were all sitting in a room in front of a television; in the age of the DRS, the umpire has gone from being the expert match manager to all-purpose match clerk. On its own, the change in umpire's call is not the worst idea, even if it is an unnecessary change. But it is a signal that a bad argument has won - another milestone towards the end of the umpire's expertise.