Kleptocrats, fraudsters and crooks steal hundreds of billions of pounds, dollars and euros from the rest of us every year, but that gives them a problem: how can they stop the rest of us knowing what they’ve done with the proceeds? They have to stop their haul looking suspicious, to cleanse it of any criminal taint, or face losing their hard-stolen cash.

Money laundering, as this process is known, is notoriously difficult to uncover, investigate and prosecute. Occasionally, however, an insider breaks cover – someone such as Howard Wilkinson, who blew the whistle on perhaps the largest money-laundering scheme in history, the movement of €200bn of suspect funds through the Estonian branch of Denmark’s biggest bank between 2007 and 2015, most of it earned in the dodgier corners of the former Soviet Union, some perhaps belonging to Vladimir Putin himself.

“No one really knows where this money went,” Wilkinson, a former Danske Bank employee, told Denmark’s parliament last year. Once the money had got into the global financial system, “it was clean, it was free.”

Britain’s most famous money launderer is HSBC, thanks to its systematic cleansing of the earnings of the Latin American drug cartels over the second half of the last decade, for which it was fined $1.9bn by the US government in 2012. But that was a tiny operation compared to the Danske Bank scandal. If gathered together, the suspect funds moved through the bank’s Estonian outpost could buy HSBC, with more than enough left over to buy Danske Bank too.

The scandal has been big news in Denmark and Estonia, but barely grazed public consciousness in the UK. This is strange, because Britain played a key role. All of the owners of the bank accounts that first aroused Wilkinson’s suspicions had their identity hidden behind corporate structures registered in the UK – including Lantana Trade LLP, the one that may have been connected to Putin. That means this is not just a Russian, Estonian or Danish scandal, but something far closer to home. In November, Wilkinson told a European parliament committee that the countries hosting these companies are just as culpable. “Worst of all is the United Kingdom,” he said. “The United Kingdom is an absolute disgrace.”

The British government is supposedly committed to tackling grand corruption and financial crime, yet Britain’s involvement in this mega-scandal has never been mentioned in parliament, or been addressed by ministers. It is far from the first time that British companies have been involved in high-profile money-laundering. Among the characters who have used British shell companies to hide their money are Paul Manafort, disgraced former chairman of Donald Trump’s election campaign, and Viktor Yanukovich, overthrown president of Ukraine, among thousands of lower-profile opportunists.

It is increasingly hard to avoid the conclusion that Britain tolerates this kind of behaviour deliberately, because of the money it brings into to our economy.

That being so, why should hardened criminals be the only ones getting rich off Britain’s lax enforcement? Here’s how you too can use British shell companies to cleanse your dirty money – in five easy steps.

Step 1: Forget what you think you know

If you have ambitions to steal a lot of money, forget about using cash. Cash is cumbersome, risky and highly limiting. Even if Danske Bank had used the highest denomination banknotes available to it, that €200bn would have weighed 400 tonnes, an amount four times heavier than a blue whale. Just moving it would have been a serious logistical challenge, let alone hiding it. It would have been a magnet for thieves, and would have attracted some unwelcome questions at customs.

If you want to commit significant financial crime, therefore, you need a bank account, because electronic cash weighs nothing, no matter how much of it there is. But that causes a new problem: the bank account will have your name on it, which will alert the authorities to your identity if they come looking.

This is where shell companies come in. Without a company, you have to act in person, which means your involvement is obvious and overt: the bank account is in your name. But using a company to own that bank account is like robbing a house with gloves on – it leaves no fingerprints, as long as the company’s ownership information is hidden from the authorities. This is why all sensible crooks do it.

The next question is what jurisdiction you will choose to register your shell company in. If you Google “offshore finance”, you’ll see photos of tropical islands with palm trees, white sands and turquoise waters. These represent the kind of jurisdictions – “sunny places for shady people” – where we expect to find shell companies. For decades, places such as Anguilla, the British Virgin Islands, Gibraltar and others sold the companies that people hide behind when committing their crimes. But in recent years, the world has changed – those jurisdictions have been cajoled, bullied and persuaded to keep good records of company ownership, and to reveal those records when police officers come looking. They are no longer as useful as they used to be.

So where is? This is where the UK comes in. When it comes to financial crime, Britain is your best friend.

Here is the secret you need to know to get started in the shell company game: the British company registration system contains a giant loophole – the kind of loophole you can drive a billion euros through without touching the sides. That is why UK shell companies have enabled financial crime all over the world, from giant acts of kleptocratic plunder to sad and squalid frauds that rob pensioners of their retirement savings.

So, step one: forget what you think you know about offshore finance. The true image associated with “shell companies” these days should not be an exotic island redolent of the sound of the sea and the smell of rum cocktails, but a damp-stained office block in an unfashionable London suburb, or a nondescript street in a northern city. If you want to set up in the money-laundering business, you don’t need to move to the Caribbean: you’d be far better off doing it from the comfort of your own home.

Step 2: Set up a company

The second step is easy, and involves creating a company on the Companies House website. Companies House maintains the UK’s registry of corporate structures and publishes information on shareholders, directors, accounts, partners and so on, so anyone can check up on their bona fides.

Setting up a company costs £12 and takes less than 24 hours. According to the World Bank’s annual Doing Business report, the UK is one of the easiest places anywhere to create a company, so you’ll find the process pretty straightforward.

This is another reason not to bother with places like the British Virgin Islands: setting up a company there will cost you £1,000, and you’ll have to go through an agent who will insist on checking your identity before doing business with you. Global agreements now require agents to verify their clients’ identity, to conduct the same kind of “due diligence” process demanded when opening a bank account. Almost all the traditional tax havens have been forced to comply with the rules, or face being blacklisted by the world’s major economies.

This means there are now few jurisdictions left where you can create a genuinely anonymous shell company – and those that remain look so dodgy that your company will practically scream “Beware! Fraudster!” to anyone you try to do business with.

But Britain is an exception. While it has bullied the tax havens into checking up on their customers, Britain itself doesn’t bother with all those tiresome and expensive “due diligence” formalities. It is true that, while registering your company on the Companies House website, you will find that it asks for information such as your name and address. On the face of it, that might look worrying. If you have to declare your name and address, then how will your company successfully shield your identity when you engage in industrial-scale fraud?

Do not be concerned, just read on.

The second step is easy, and involves creating a company on the Companies House website. Companies House maintains the UK’s registry of corporate structures and publishes information on shareholders, directors, accounts, partners and so on, so anyone can check up on their bona fides.

Setting up a company costs £12 and takes less than 24 hours. According to the World Bank’s annual Doing Business report, the UK is one of the easiest places anywhere to create a company, so you’ll find the process pretty straightforward.

This is another reason not to bother with places like the British Virgin Islands: setting up a company there will cost you £1,000, and you’ll have to go through an agent who will insist on checking your identity before doing business with you. Global agreements now require agents to verify their clients’ identity, to conduct the same kind of “due diligence” process demanded when opening a bank account. Almost all the traditional tax havens have been forced to comply with the rules, or face being blacklisted by the world’s major economies.

This means there are now few jurisdictions left where you can create a genuinely anonymous shell company – and those that remain look so dodgy that your company will practically scream “Beware! Fraudster!” to anyone you try to do business with.

But Britain is an exception. While it has bullied the tax havens into checking up on their customers, Britain itself doesn’t bother with all those tiresome and expensive “due diligence” formalities. It is true that, while registering your company on the Companies House website, you will find that it asks for information such as your name and address. On the face of it, that might look worrying. If you have to declare your name and address, then how will your company successfully shield your identity when you engage in industrial-scale fraud?

Do not be concerned, just read on.

Step 3: Make stuff up

This third step may be the hardest to really take in, because it seems too simple. Since 2016, the UK government has made it compulsory for anyone setting up a company to name the individual who actually owns it: “the person with significant control”, or PSC. Before this reform it was possible to own a company with another company and, if that company was not British, the actual owner could hide their identity.

In theory, the introduction of the PSC rule should have prevented the use of a British shell company to anonymously commit financial crime. Don’t worry though, because it didn’t. Here is the secret: no one checks the accuracy of the information you provide when you register with Companies House. You can say pretty much anything and Companies House will accept it.

So this is step three: when you’re entering the information to create your company, make mistakes. Suspicious typos are everywhere once you start delving into the Companies House database. For instance, many money-laundering investigations involving the former USSR eventually bump against a Belgian-based dentist, whose signature adorns the accounts of hundreds, if not thousands, of different companies, including Lantana Trade LLP. When he was tracked down to his home address in Belgium last year, the dentist claimed that his signature had been forged and that he had no connection to the companies. Whoever was filing the documents was remarkably imaginative when it came to spelling his name. Every document filed with the UK registry has the same signature, but his name is spelt in at least eight different ways: Ali Moulaye, Alli Moulaye, Aly Moulaye, Ali Moyllae, Ali Moulae, Ali Moullaye, Aly Moullaye and, oddly, Ian Virel.

With such boundless opportunities for creativity, why not have fun? Recently, while messing about on the Companies House website, I came across a PSC named Mr Xxx Stalin, who is apparently a Frenchman resident in east London. It is perhaps technically possible that Xxx is a genuine name given to Mr Stalin by eccentric parents – but, if so, such eccentric parents are remarkably widespread.

Xxx Stalin led me to a PSC of a different company, who was named Mr Kwan Xxx, a Kazakh citizen, resident in Germany; then to Xxx Raven; to Miss Tracy Dean Xxx; to Jet Xxx; and finally to (their distant cousin?) Mr Xxxx Xxx. These rabbitholes are curiously engrossing, and before long I’d found Mr Mmmmmmm Yyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyy, and Mr Mmmmmm Xxxxxxxxxxx (correspondence address: Mmmmmmm, Mmmmmm, Mmm, MMM), at which point I decided to stop.

As trolling goes, it is quite funny, but the implications are also very serious, if you think about what companies are supposed to be for. Limited companies and partnerships have their liability for debts limited, which means that if they go bust, their investors are not personally bankrupted. It’s a form of insurance – society as a whole is accepting responsibility for entrepreneurs’ debts, because we want to encourage entrepreneurial behaviour. In return, entrepreneurs agree to publish details about their companies so we can all check what they are up to, and to make sure they’re not abusing our trust.

The whole point of the PSC registry was to stop fraudsters obscuring their identities behind shell companies, and yet, thanks to Companies House’s failure to check the information provided to it and thus to enforce the rules, they are still doing so. How exactly could society find someone who gives their identity as Mr Xxxxxxxxxxx, and their address as the chorus of a Crash Test Dummies song?

Even when the company documents provide an actual name, rather than a random selection of letters, the information is often very hard to believe. For example, in September, Companies House registered Atlas Integrate Services LLP, which declared a PSC with a date of birth that showed her to be just two months old at the time. In her two months of life, she had not only found time to get started in business, but also apparently to get married, since she was listed as “Mrs”. The LLP’s incorporation document states: “This person holds the right, directly or indirectly, to appoint or remove a majority of the persons who are entitled to take part in the management of the LLP”. It does not explain how exactly a babe in arms would achieve this.

This is not a one-off. The anti-corruption campaign group Global Witness looked into PSCs last year, and found 4,000 of them were under the age of two. One hadn’t even been born yet. At the opposite end of the spectrum, its researchers found five individuals who each controlled more than 6,000 companies. There are more than 4m companies at Companies House, which is a very large haystack to hide needles in.

You don’t actually even need to list a person as your company’s PSC. It’s permissible to say that your company doesn’t know who owns it (no, you’re not misunderstanding; that just doesn’t make sense), or simply to tie the system up in knots by listing multiple companies in multiple jurisdictions that no investigator without the time and resources of the FBI could ever properly check.

This is why step three is such an important one in the five-step pathway to creating a British shell company. If you can invent enough information when filing company accounts, then the calculation that underpins the whole idea of a company goes out of the window: you gain the protection from legal action, without giving up anything in return. It’s brilliant.

But don’t dive in just yet; there are two more steps to follow before you can be confident of doing it properly.

This third step may be the hardest to really take in, because it seems too simple. Since 2016, the UK government has made it compulsory for anyone setting up a company to name the individual who actually owns it: “the person with significant control”, or PSC. Before this reform it was possible to own a company with another company and, if that company was not British, the actual owner could hide their identity.

In theory, the introduction of the PSC rule should have prevented the use of a British shell company to anonymously commit financial crime. Don’t worry though, because it didn’t. Here is the secret: no one checks the accuracy of the information you provide when you register with Companies House. You can say pretty much anything and Companies House will accept it.

So this is step three: when you’re entering the information to create your company, make mistakes. Suspicious typos are everywhere once you start delving into the Companies House database. For instance, many money-laundering investigations involving the former USSR eventually bump against a Belgian-based dentist, whose signature adorns the accounts of hundreds, if not thousands, of different companies, including Lantana Trade LLP. When he was tracked down to his home address in Belgium last year, the dentist claimed that his signature had been forged and that he had no connection to the companies. Whoever was filing the documents was remarkably imaginative when it came to spelling his name. Every document filed with the UK registry has the same signature, but his name is spelt in at least eight different ways: Ali Moulaye, Alli Moulaye, Aly Moulaye, Ali Moyllae, Ali Moulae, Ali Moullaye, Aly Moullaye and, oddly, Ian Virel.

With such boundless opportunities for creativity, why not have fun? Recently, while messing about on the Companies House website, I came across a PSC named Mr Xxx Stalin, who is apparently a Frenchman resident in east London. It is perhaps technically possible that Xxx is a genuine name given to Mr Stalin by eccentric parents – but, if so, such eccentric parents are remarkably widespread.

Xxx Stalin led me to a PSC of a different company, who was named Mr Kwan Xxx, a Kazakh citizen, resident in Germany; then to Xxx Raven; to Miss Tracy Dean Xxx; to Jet Xxx; and finally to (their distant cousin?) Mr Xxxx Xxx. These rabbitholes are curiously engrossing, and before long I’d found Mr Mmmmmmm Yyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyy, and Mr Mmmmmm Xxxxxxxxxxx (correspondence address: Mmmmmmm, Mmmmmm, Mmm, MMM), at which point I decided to stop.

As trolling goes, it is quite funny, but the implications are also very serious, if you think about what companies are supposed to be for. Limited companies and partnerships have their liability for debts limited, which means that if they go bust, their investors are not personally bankrupted. It’s a form of insurance – society as a whole is accepting responsibility for entrepreneurs’ debts, because we want to encourage entrepreneurial behaviour. In return, entrepreneurs agree to publish details about their companies so we can all check what they are up to, and to make sure they’re not abusing our trust.

The whole point of the PSC registry was to stop fraudsters obscuring their identities behind shell companies, and yet, thanks to Companies House’s failure to check the information provided to it and thus to enforce the rules, they are still doing so. How exactly could society find someone who gives their identity as Mr Xxxxxxxxxxx, and their address as the chorus of a Crash Test Dummies song?

Even when the company documents provide an actual name, rather than a random selection of letters, the information is often very hard to believe. For example, in September, Companies House registered Atlas Integrate Services LLP, which declared a PSC with a date of birth that showed her to be just two months old at the time. In her two months of life, she had not only found time to get started in business, but also apparently to get married, since she was listed as “Mrs”. The LLP’s incorporation document states: “This person holds the right, directly or indirectly, to appoint or remove a majority of the persons who are entitled to take part in the management of the LLP”. It does not explain how exactly a babe in arms would achieve this.

This is not a one-off. The anti-corruption campaign group Global Witness looked into PSCs last year, and found 4,000 of them were under the age of two. One hadn’t even been born yet. At the opposite end of the spectrum, its researchers found five individuals who each controlled more than 6,000 companies. There are more than 4m companies at Companies House, which is a very large haystack to hide needles in.

You don’t actually even need to list a person as your company’s PSC. It’s permissible to say that your company doesn’t know who owns it (no, you’re not misunderstanding; that just doesn’t make sense), or simply to tie the system up in knots by listing multiple companies in multiple jurisdictions that no investigator without the time and resources of the FBI could ever properly check.

This is why step three is such an important one in the five-step pathway to creating a British shell company. If you can invent enough information when filing company accounts, then the calculation that underpins the whole idea of a company goes out of the window: you gain the protection from legal action, without giving up anything in return. It’s brilliant.

But don’t dive in just yet; there are two more steps to follow before you can be confident of doing it properly.

Step 4: Lie – but do so cleverly

Most of the daft examples earlier (Mmmmmmm, Mmmmmm, Mmm, MMM) would not be useful for committing fraud, since anyone looking at them can tell they’re not serious. Cumberland Capital Ltd, however, was a different matter. It looked completely legitimate.

It controlled a company called Tropical Trade, which, in October 2016, cold-called a 63-year-old retired postal worker in Wisconsin identified in court filings as “MJ”. On the phone, a salesman offered her an investment product, which – he said – would make returns of 81%. He chatted about his wife and family and came across as “kind and trustworthy”, MJ later told police. “During two weeks in November of 2016, she allowed Tropical Trade to charge $34,500 on her Mastercard and Visa credit cards,” the filing states. When she tried to get her money back, her emails and calls were ignored, and she never saw it again.

She had fallen victim to the global epidemic of binary-options fraud. Binary options are a form of betting on the stock market that are now banned in many countries – including Israel, where much of the industry was based – since fraudsters used the idea to fix odds, keep winnings and target the vulnerable. According to the FBI, taken as a whole, these fraudsters may have been fleecing their marks of up to $10bn a year.

When US police came looking for the people behind Cumberland Capital Ltd, they searched the Companies House website and found that its director was an Australian citizen called Manford Martin Mponda. Anyone researching binary-options fraud might quickly conclude that Mponda was a kingpin. He was a serial company director, with some 80 directorships in UK-registered companies to his name, and features in dozens of complaints.

It already looked like a major scandal that British regulation was so lax that Mponda could have been allowed to conduct a global fraud epidemic behind the screen of UK-registered companies, but the reality was even more remarkable: Mponda had nothing to do with it. He was a victim, too.

Police officers suspect that, after Mponda submitted his details to join a binary-options website, his identity was stolen so it could be used to register him as a director of dozens of UK companies. The scheme was only exposed after complaints to consumer protection bodies were passed onto the City of London police, who then asked their Australian colleagues to investigate.

Companies House has since deleted Mponda’s name from documents related to dozens of other companies, but it was too late for “MJ” and thousands of other victims. A small number of the binary-options masterminds have been caught, but the money they stole has vanished into the labyrinth of interlocking shell companies, and the individuals behind Cumberland Capital have not been identified.

“Most of the binary-options firms claimed to be in the UK. People are more likely to deal with a UK company than a company in Israel, as it has a better reputation when it comes to finances,” said DS Alex Eristavi of the City of London Police’s investment fraud team. “Companies House records are provided in good faith. There’s not so much scrutiny as goes on in, say, Italy or Spain, where you have to go through the lawyers and do it properly. Here the information is submitted voluntarily. People don’t realise that, they take it as being carved in stone.”

So here is step four: don’t just lie, lie cleverly. British companies look legitimate, so look legitimate yourself. Steal a real person’s name, and put that on the company documents. Don’t put your own address on the documents, rent a serviced office to take your post: Paul Manafort used one in Finchley, the binary options fraudsters went to Liverpool, and Lantana Trade was based in the London suburb of Harrow.

The financial documents you file look better if they’ve been audited by an accountant, so file genuine-looking accounts, and claim they’ve been audited by a proper accountancy firm. That isn’t checked either, so just find an accountant online and claim you’ve employed them. Accountants quite regularly find themselves contacted about accounts they have never seen before, and make the unwelcome discovery they have been personally named as having approved them.

Most of the daft examples earlier (Mmmmmmm, Mmmmmm, Mmm, MMM) would not be useful for committing fraud, since anyone looking at them can tell they’re not serious. Cumberland Capital Ltd, however, was a different matter. It looked completely legitimate.

It controlled a company called Tropical Trade, which, in October 2016, cold-called a 63-year-old retired postal worker in Wisconsin identified in court filings as “MJ”. On the phone, a salesman offered her an investment product, which – he said – would make returns of 81%. He chatted about his wife and family and came across as “kind and trustworthy”, MJ later told police. “During two weeks in November of 2016, she allowed Tropical Trade to charge $34,500 on her Mastercard and Visa credit cards,” the filing states. When she tried to get her money back, her emails and calls were ignored, and she never saw it again.

She had fallen victim to the global epidemic of binary-options fraud. Binary options are a form of betting on the stock market that are now banned in many countries – including Israel, where much of the industry was based – since fraudsters used the idea to fix odds, keep winnings and target the vulnerable. According to the FBI, taken as a whole, these fraudsters may have been fleecing their marks of up to $10bn a year.

When US police came looking for the people behind Cumberland Capital Ltd, they searched the Companies House website and found that its director was an Australian citizen called Manford Martin Mponda. Anyone researching binary-options fraud might quickly conclude that Mponda was a kingpin. He was a serial company director, with some 80 directorships in UK-registered companies to his name, and features in dozens of complaints.

It already looked like a major scandal that British regulation was so lax that Mponda could have been allowed to conduct a global fraud epidemic behind the screen of UK-registered companies, but the reality was even more remarkable: Mponda had nothing to do with it. He was a victim, too.

Police officers suspect that, after Mponda submitted his details to join a binary-options website, his identity was stolen so it could be used to register him as a director of dozens of UK companies. The scheme was only exposed after complaints to consumer protection bodies were passed onto the City of London police, who then asked their Australian colleagues to investigate.

Companies House has since deleted Mponda’s name from documents related to dozens of other companies, but it was too late for “MJ” and thousands of other victims. A small number of the binary-options masterminds have been caught, but the money they stole has vanished into the labyrinth of interlocking shell companies, and the individuals behind Cumberland Capital have not been identified.

“Most of the binary-options firms claimed to be in the UK. People are more likely to deal with a UK company than a company in Israel, as it has a better reputation when it comes to finances,” said DS Alex Eristavi of the City of London Police’s investment fraud team. “Companies House records are provided in good faith. There’s not so much scrutiny as goes on in, say, Italy or Spain, where you have to go through the lawyers and do it properly. Here the information is submitted voluntarily. People don’t realise that, they take it as being carved in stone.”

So here is step four: don’t just lie, lie cleverly. British companies look legitimate, so look legitimate yourself. Steal a real person’s name, and put that on the company documents. Don’t put your own address on the documents, rent a serviced office to take your post: Paul Manafort used one in Finchley, the binary options fraudsters went to Liverpool, and Lantana Trade was based in the London suburb of Harrow.

The financial documents you file look better if they’ve been audited by an accountant, so file genuine-looking accounts, and claim they’ve been audited by a proper accountancy firm. That isn’t checked either, so just find an accountant online and claim you’ve employed them. Accountants quite regularly find themselves contacted about accounts they have never seen before, and make the unwelcome discovery they have been personally named as having approved them.

Steps 1-4: A brief recap

So, to summarise the tricks so far, if you want to create an impenetrable weapon for committing fraud: first, forget about the supposed offshore centres and come to the UK; then take advantage of the super-easy Companies House web portal; then enter false information; and finally make sure that information is plausible enough to deceive a casual observer.

We’re nearly there. It’s time for the final step.

Step 5: Don’t worry about it

I know what you’re thinking: it cannot be this easy. Surely you’ll be arrested, tried and jailed if you try to follow this five-step process. But if you look at what British officials do, rather than at what they say, you’ll begin to feel a lot more secure. The Business Department has repeatedly been warned that the UK is facilitating this kind of financial crime for the best part of a decade, and is yet to take any substantive action to stop it. (Though, to be fair, it did recently launch a “consultation”.)

Before 2011, only registered company-formation businesses could access Companies House’s web portal, which meant there was a clear connection between an actual verified individual and companies being created, since you could see who had created them. There was still fraud, of course, but it was relatively easy to understand who was responsible.

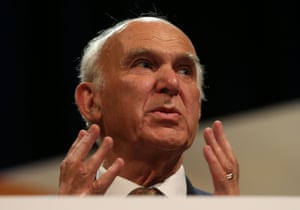

In 2011, then-business secretary and Liberal Democrat MP Vince Cable decided to open up Companies House, and everything changed. After Cable’s reform, anyone with an internet connection, anywhere in the world, could create a UK company in about as much time as it takes to order a couple of pizzas, and for approximately the same amount of money. The checks were gone; there was no longer any connection to a verifiably existing person; it was as easy to create a UK company as it was to set up a Twitter account. The rationale was that this would unleash the latent entrepreneurship within the British nation by making it easy to turn business ideas into thriving concerns.

Instead of unchaining a new generation of British businesspeople, however, Cable let slip the dogs of fraud. At first, this rather technical modification to an obscure corner of the British machinery of state did not garner much attention, but for people who understood what it meant it was alarming. One such person was Kevin Brewer, a Warwickshire businessman who had been in the company forming business for decades, and who attempted to warn Cable of the potential risks inherent in the new policy.

The method Brewer chose to make his warning was perhaps slightly unwise. He registered a company – John Vincent Cable Services Ltd – with Vince Cable listed as the sole shareholder, then wrote to the business secretary to explain what he had done. It was intended as a demonstration of how easy it is to file unverified information with Companies House, but it failed to focus attention in the way he had hoped. Jo Swinson MP, who worked with Cable, wrote Brewer a stern letter, telling him he should not have done what he did, and assured him that the new system was very good. Brewer concluded that the coalition government was not going to take his concerns seriously.

In 2015, there was a general election, Cable lost his seat, the Conservatives formed a majority government, and Brewer decided to try again with the same stunt. He created Cleverly Clogs Ltd, a company apparently owned by three people: James Cleverly MP, Baroness Neville-Rolfe, who was a minister in the business department, and a fictional Israeli called Ibrahim Aman. Brewer was no more successful in persuading Tories than he had been at persuading Liberal Democrats, however. At that point, he gave up on his attempt to show the government it was enabling limitless opportunities for fraud.

There is, it turns out, a simple explanation for why successive governments have failed to do anything about it. Last year, when challenged in the House of Commons, Treasury minister John Glen stated that Companies House simply couldn’t afford to check the information filed with it, since that would cost the UK economy hundreds of millions of pounds a year. This is almost certainly an exaggeration. Anti-corruption activists who have looked at the data say the cost would in fact be far less than that, but the key point is that the reform would pay for itself. As Brewer has pointed out, “the burden of cost is one thing. But the cost of fraud is far greater.”

VAT fraud alone costs the UK more than £1bn a year, while the National Crime Agency estimates the cost of all fraud to the UK economy to be £190bn. The cost to the rest of the world of the money laundering enabled by UK corporate entities is almost certainly far higher. Spending hundreds of millions of pounds to prevent hundreds of billions’ worth of crime looks like a sensible investment, however you look at the data, particularly since the remedy – obliging Companies House to check the accuracy of the information filed on its registry – would be so simple. (When I put this to Companies House, they provided the following statement: “We do not have the statutory power or capability to verify the accuracy of the information that companies provide. However, tackling abuse of the register is a key priority and that’s why we work closely with law enforcement partners to assist their investigations into suspected cases of economic crime and other offences.”)

That is not to say that the government has taken no action. It is illegal to deliberately file false information in registering a company, and punishable by up to two years in prison. In late 2017, Companies House at last alerted prosecutors to the activities of one persistent offender. The target of the prosecution was Kevin Brewer, for the crime of trying to inform politicians about how easy it is to create fake companies.

He was summonsed to appear at Redditch magistrates’ court and, on legal advice, pleaded guilty in March 2018. After adding together his fine, and the government’s costs, he is £23,324 the poorer – quite a high price to pay for blowing the whistle. He is paying it off at £1,000 a month, and remains the only person ever convicted of spoofing the UK’s corporate registry, which is quite a remarkable demonstration of Companies House’s failure to do its job.

I know what you’re thinking: it cannot be this easy. Surely you’ll be arrested, tried and jailed if you try to follow this five-step process. But if you look at what British officials do, rather than at what they say, you’ll begin to feel a lot more secure. The Business Department has repeatedly been warned that the UK is facilitating this kind of financial crime for the best part of a decade, and is yet to take any substantive action to stop it. (Though, to be fair, it did recently launch a “consultation”.)

Before 2011, only registered company-formation businesses could access Companies House’s web portal, which meant there was a clear connection between an actual verified individual and companies being created, since you could see who had created them. There was still fraud, of course, but it was relatively easy to understand who was responsible.

In 2011, then-business secretary and Liberal Democrat MP Vince Cable decided to open up Companies House, and everything changed. After Cable’s reform, anyone with an internet connection, anywhere in the world, could create a UK company in about as much time as it takes to order a couple of pizzas, and for approximately the same amount of money. The checks were gone; there was no longer any connection to a verifiably existing person; it was as easy to create a UK company as it was to set up a Twitter account. The rationale was that this would unleash the latent entrepreneurship within the British nation by making it easy to turn business ideas into thriving concerns.

Instead of unchaining a new generation of British businesspeople, however, Cable let slip the dogs of fraud. At first, this rather technical modification to an obscure corner of the British machinery of state did not garner much attention, but for people who understood what it meant it was alarming. One such person was Kevin Brewer, a Warwickshire businessman who had been in the company forming business for decades, and who attempted to warn Cable of the potential risks inherent in the new policy.

The method Brewer chose to make his warning was perhaps slightly unwise. He registered a company – John Vincent Cable Services Ltd – with Vince Cable listed as the sole shareholder, then wrote to the business secretary to explain what he had done. It was intended as a demonstration of how easy it is to file unverified information with Companies House, but it failed to focus attention in the way he had hoped. Jo Swinson MP, who worked with Cable, wrote Brewer a stern letter, telling him he should not have done what he did, and assured him that the new system was very good. Brewer concluded that the coalition government was not going to take his concerns seriously.

In 2015, there was a general election, Cable lost his seat, the Conservatives formed a majority government, and Brewer decided to try again with the same stunt. He created Cleverly Clogs Ltd, a company apparently owned by three people: James Cleverly MP, Baroness Neville-Rolfe, who was a minister in the business department, and a fictional Israeli called Ibrahim Aman. Brewer was no more successful in persuading Tories than he had been at persuading Liberal Democrats, however. At that point, he gave up on his attempt to show the government it was enabling limitless opportunities for fraud.

There is, it turns out, a simple explanation for why successive governments have failed to do anything about it. Last year, when challenged in the House of Commons, Treasury minister John Glen stated that Companies House simply couldn’t afford to check the information filed with it, since that would cost the UK economy hundreds of millions of pounds a year. This is almost certainly an exaggeration. Anti-corruption activists who have looked at the data say the cost would in fact be far less than that, but the key point is that the reform would pay for itself. As Brewer has pointed out, “the burden of cost is one thing. But the cost of fraud is far greater.”

VAT fraud alone costs the UK more than £1bn a year, while the National Crime Agency estimates the cost of all fraud to the UK economy to be £190bn. The cost to the rest of the world of the money laundering enabled by UK corporate entities is almost certainly far higher. Spending hundreds of millions of pounds to prevent hundreds of billions’ worth of crime looks like a sensible investment, however you look at the data, particularly since the remedy – obliging Companies House to check the accuracy of the information filed on its registry – would be so simple. (When I put this to Companies House, they provided the following statement: “We do not have the statutory power or capability to verify the accuracy of the information that companies provide. However, tackling abuse of the register is a key priority and that’s why we work closely with law enforcement partners to assist their investigations into suspected cases of economic crime and other offences.”)

That is not to say that the government has taken no action. It is illegal to deliberately file false information in registering a company, and punishable by up to two years in prison. In late 2017, Companies House at last alerted prosecutors to the activities of one persistent offender. The target of the prosecution was Kevin Brewer, for the crime of trying to inform politicians about how easy it is to create fake companies.

He was summonsed to appear at Redditch magistrates’ court and, on legal advice, pleaded guilty in March 2018. After adding together his fine, and the government’s costs, he is £23,324 the poorer – quite a high price to pay for blowing the whistle. He is paying it off at £1,000 a month, and remains the only person ever convicted of spoofing the UK’s corporate registry, which is quite a remarkable demonstration of Companies House’s failure to do its job.

Following his conviction, Brewer’s company National Business Register was removed from the list that Companies House publishes of company formation agents, which had been a key source of new business for him. “There are company formation agents on that list who have permitted huge amounts of fraud, and I’ve been excluded for trying to expose it. I find it incredible that they should turn a blind eye,” he told me. “Is it deliberate? Are they actually trying to get this money into the UK? I don’t want to believe it, but I can’t explain it any other way.”

We don’t know the answer to that, but it does give us lesson number five: don’t worry about it. Commit as much fraud as you like, fill your boots, the only reason anyone would care is if you kick up a fuss. And what sensible fraudster is going to do that?

,

,