Officials get fed up with accusations that Britain is a cesspool of dirty money; that they do too little to check the wealth hidden behind shell corporations. They grouse among themselves that their critics overlook the work they’re doing to expose the money flows and to drive out the corrupt.

When they do get a win, therefore, they trumpet it. Last month, Companies House successfully prosecuted someone who had lied in setting up a company, the kind of white-collar crime committed by the sophisticated fraudsters who fleece ordinary Brits every day, and the government went large. “This prosecution – the first of its kind in the UK – shows the government will come down hard on people who knowingly break the law and file false information on the company register,” crowed business minister, Andrew Griffiths, in a press release.

A Warwickshire businessman called Kevin Brewer had pleaded guilty, paid a fine and the government’s costs: a total of more than £12,000. His crime had been to falsely claim that two companies he created belonged, in one case, to the MP Vince Cable, and, in the other, to the MP James Cleverly, Lady Neville-Rolfe and an imaginary Israeli. At first, the public response to the news was everything the press release’s authors could have hoped for. The Times splashed with the details of the crime – the government was tough on fraud, tough on the causes of fraud. But the victory was short-lived. Within a month of the triumphant press release, Tory MP John Penrose, the government’s anti-corruption champion, was slamming the prosecution as “a bone-headed exercise in shooting the messenger”. Brewer may have been, by his own admission, naive, but he was trying to expose a flaw in British regulations that enables frauds totalling hundreds of billions of pounds. His reward was years of being ignored and, finally, a criminal record. “That has to be wrong,” said Penrose.

Lady Neville-Rolfe was minister responsible for Companies House when Kevin Brewer set up a company that included her as a director and shareholder. Photograph: Richard Gardner/REX/Shutterstock

The 4m corporate vehicles in the British registry are the building blocks of our economy, crucial to our prosperity. Hidden among them, however, like pickpockets in a crowd, are thousands of fake companies used by fraudsters to commit their crimes. Companies let criminals look legitimate and make their frauds, tax evasion or kleptocracy resemble normal business activity.

These fake companies have tell-tale flaws: invented addresses, offshore ownership, dormant companies acting as other companies’ directors. The strange thing about Brewer’s companies, however, is that they did not have these flaws. They were registered to Brewer’s address; his business acted as their agent; he wrote to the MPs and the peer to tell them he had created companies in their names; and he dissolved the companies after he’d done so.

If he was a criminal, he was a very strange one: a bank robber who took no money, left his business card on the counter and wrote the manager a letter confessing to the crime. Yet, while real bank robbers are getting away with theft all around us, Brewer ended up in court. His is a story that goes to the heart of Britain’s ramshackle approach to tackling money laundering and exposes our shameful failure to combat a crime that spreads far beyond our borders.

Brewer, who turned 66 on Saturday, is a company formation agent and reckons he has created half-a-million corporate vehicles since 1984. “It grew into a national enterprise, forming companies for anybody in the country,” he told me. “My main clients were solicitors and accountants, professional clients more than the public, because of – I’d like to say – the quality of the service.”

Part of that service was a rigorous due diligence process: he checked his client’s identity, the source of their funds and the purpose of their company. Often, investigators from the police or the Revenue & Customs would ask to look at his files and he would help them discover who was behind a company that had committed a crime. “I’ve given witness statements in very large trials. The Serious Fraud Office sent me a thank-you letter,” he said.

For the price of fish and chips, anyone could log in, form a company, put in any name they liked – Mickey MouseKevin Brewer

His problems began in 2011 under the coalition government, when business secretary Vince Cable opened up Companies House’s online registration system. As part of a drive to make the country more entrepreneurial, anyone could now register a company via the registry’s web portal, rather than doing it on paper or going via an intermediary such as Brewer. You may remember the “Britain Is Great” advertising campaign from bus stops in 2012: one strapline boasted that it took less than 24 hours to incorporate in the UK. Ministers thought this was good; Brewer thought it was awful.

“For the price of some fish and chips, anyone in the world could log in, form a company, put in any name they liked, Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, somebody else’s name, totally fictitious names, get their companies formed and get their certificate,” he said. “You could be in Russia, Jamaica, anywhere.”

Where Brewer had charged £100 for a company, Companies House charged £18; where he checked his client’s intentions and identity, Companies House didn’t check anything. This threatened his business, but it also threatened to unleash fraud on a scale never before seen. He felt sure the government hadn’t considered the consequences of its policy, so he wrote to Cable. “Not only is the policy misguided and costly, it has created massive opportunity for fraud and deception,” Brewer wrote. “To illustrate the point we have created a company in your name without your consent or knowledge and could start trading using your identity.” John Vincent Cable Services Ltd had been incorporated on 23 May 2013, with a single shareholder – the business secretary.

Illustration: Dom McKenzie

Jo Swinson MP replied on behalf of Cable, explaining at length why Companies House was not covered by anti-money laundering regulations. She also warned that he had committed a criminal offence in creating the fake company, but that she didn’t want to see him prosecuted. The Daily Mirror wrote it up as a curious oddity and that was the end of the matter.

A spokesman for the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) was careful to point out to me last week that Brewer was not being altruistic when he made his warning to Cable: he was losing business as a result of the changes to Companies House. Although this is true, it does not detract from the fact that Brewer had a point.

British corporate vehicles have enabled fraud on a global scale. The former president of Ukraine used British companies to conceal his property, as did his cronies. The “Russian laundromat”, a complex money-laundering scheme that moved $21m out of Russia, was run through Scottish limited partnerships. Transparency International UK (TI-UK) last year analysed 52 corruption cases and found they involved 766 British corporate vehicles, which had laundered some £80bn. “The human damage inflicted on the victims of these crimes is still being counted,” it said, in its report Hiding In Plain Sight.

Sophisticated financial crime is impossible without corporate vehicles. Carousel fraud, a scam in which traders import goods, sell them to themselves via related companies, before exporting them and claiming back VAT that they never paid, costs the UK £500m to £1bn a year and that is just one category of crime. The UK as a whole loses as much as £193bn a year from fraud, while perhaps another £100bn is laundered through the country’s financial system, according to a National Crime Agency (NCA) report from last year.

In an attempt to stop this happening, David Cameron’s government obliged UK companies to declare a person with significant control (PSC – someone who actually owns the shares) and made it free to search Companies House so as to increase public scrutiny. The trouble is that no one at Companies House is checking the accuracy of the information submitted. No matter how transparent something is, the old tech rule applies: garbage in, garbage out.

There is a cottage industry of activists seeking discrepancies in Companies House’s data in an attempt to make it do something about this problem. In January, Global Witness analysed PSC entries and found 4,000 toddlers owning companies, as well as one beneficial owner who was yet to be born. Graham Barrow, a City expert on financial crime who is currently working at Deutsche Bank, likes to post amusing cases on his LinkedIn page. A recent example documented the adventures of a man who had spelled his name six different ways, thus foiling attempts to search for him electronically.

However, Companies House doesn’t appear to respond to such revelations. I wrote an article in 2016 that featured a serial company director whose career had been unimpeded by her death four years earlier; two years on and she’s still director of an active company listed on the registry. TI-UK alerted Companies House to active companies that had been involved in the money-laundering schemes it had identified, but no noticeable action appears to have been taken against them.

“I’ve worked for a number of global banks who between them have received multimillion dollar fines and none of them was close to being as bad as Companies House with their due diligence,” Barrow told me. “Poor Kevin Brewer, I feel for him. A man tries to show how bad things are and he’s the one who ends up getting prosecuted.”

Part of the problem is the extraordinary complexity of the money-laundering regulations, which float around in an acronym soup. If an accountant or lawyer creates a company, she will be regulated by one of 22 different bodies, which are in turn overseen by the newly created Office for Professional Body Anti-Money Laundering Supervision (OPBAS), which is part of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Company formation agents such as Brewer, however, are regulated separately, although they’re doing exactly the same job. They report to HMRC, which is a non-ministerial department. When Companies House creates corporate vehicles, meanwhile, it isn’t regulated for anti-money-laundering purposes at all and is an executive agency working with BEIS.

According to Jon Benton, who retired last year after a career investigating corruption and financial crime in the Met, the NCA and the Cabinet Office, most of these agencies don’t even have software that can communicate with the others, let alone share intelligence with them. “I’m in the private sector now and I see the power of the analytical software used by financial institutions. It’s decades ahead of law enforcement,” he told me. “We criticise things in places like the British Virgin Islands, but it’s happening on our doorstep.”

In March, MPs discussed a sanctions and anti-money-laundering bill and Labour’s Anneliese Dodds, a shadow Treasury minister, proposed two amendments that would have addressed the problems identified by Brewer, TI-UK, Global Witness, Barrow, Benton and pretty much everyone else who has looked at Companies House for any length of time. One amendment sought to make the registry liable to money-laundering regulations and the other sought to block anyone not subject to UK regulations from creating UK companies.

“A huge number of companies are created without any checks. We are talking about 251,628 companies last year,” Dodds told the public bill committee. “Our proposal has been portrayed as only a burden, when it could help our constituents from being ripped off by unscrupulous individuals… they can be there by day, fly by night, and leave the unfortunate person who dealt with that company in a very difficult position.”

John Glen, a Treasury minister, replied for the government, repeating many of the same arguments that Jo Swinson used with Brewer in 2013: Companies House is just a repository of information, it has no powers to check the accuracy of what is presented to it. He also stressed that it would not be fair for legitimate companies to have to repeat the kind of identity checks they already do to open bank accounts. “The impact on resources to carry out due diligence on that number of companies would be considerable,” he said. “The overall cost to the UK economy could run into the hundreds of millions of pounds each year.”

TI-UK has also assessed the cost of the kind of changes Labour was arguing for, but came to a figure far below that of the government. It estimated that Companies House could cover the cost of the reform by raising the price of incorporation by just £5-10. That would make incorporating in the UK cost around £20, which would still be cheap by global standards. Buying a company in the British Virgin Islands costs 50 times as much. Frances Coulson, an experienced insolvency solicitor and a director of the Fraud Advisory Panel, which aims to help Britons fight financial crime, said that even a £100 fee would be a price worth paying. “This is a hole, through which people can launder money. I don’t think fixing this would be problematic for business; what’s £100 to them? And it wouldn’t cost the state anything - it’s self-funding,” she said. “There are thousands of companies on the register with nonsense information; we come across them all the time, the information is just nonsense. So the question is what sort of business would it deter? Do we want fraudsters? This wouldn’t deter legitimate business, because they need to do all the same checks to set up bank accounts anyway.”

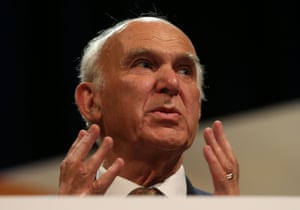

Vince Cable, in whose name Kevin Brewer set up one of his fake companies. Photograph: Andrew Matthews/PA

Dodds said that she didn’t think the government had understood the scale of the problem. The proportion of companies created directly with Companies House, rather than via regulated intermediaries, is increasing every year and is approaching 50%. If the ownership information for half of all new companies is non-verified, that brings the integrity of the entire registry into question.

“We need to be absolutely sure that London or Potters Bar, or Glasgow for that matter, are not locations for washing dirty money. Because that’s about stealing money from poor people and we really shouldn’t be helping,” she said. “The only thing that’s happened is this poor bloke has been convicted. It’s outrageous and it needn’t be that expensive to do something properly.”

After Cable lost his position following the 2015 general election, Brewer renewed his campaign with the new all-Conservative government. He wrote to MPs he thought might be sympathetic and to ministers, trying to persuade them this flaw in Britain’s anti-money-laundering defences was something they should be concerned about.

He won a friendly response from James Cleverly, leader of the Free Enterprise Group of Tory MPs, and he hoped to persuade Neville-Rolfe, who was then the minister responsible for Companies House. He decided to repeat the trick that had failed to impress Cable and incorporated a new company – Cleverly Clogs Ltd – on 17 May 2016.

Cleverly and Neville-Rolfe were shareholders and directors, alongside the fictitious Israeli Ibrahim Aman (whose home address, for some reason, Brewer listed as being in a shopping mall in Braintree). It didn’t help, however. The meeting with Cleverly was cordial, but he never got to meet Neville-Rolfe and ministers were every bit as noncommittal as their Lib-Dem predecessors. “It got nowhere; I was disillusioned and had come to the end of the road really. I didn’t think there was much more than I could do. That was 2016,” he said.

He may have been finished with Companies House, but Companies House wasn’t finished with him. An investigator from the Insolvency Service interviewed him under caution, so Brewer showed him the correspondence, explained how he’d told Companies House about his stunts, tried to tell the people whose names he’d used, explained that he’d been trying to highlight a problem. “I hadn’t done anything for nefarious purposes; I closed the companies immediately after. Nobody said I was going to get prosecuted,” he told me. “I’d just been a bit naive in my actions, which were well-intentioned, to try to get dialogue, because I felt they just didn’t understand. Every letter you got back from whatever minister was virtually word for word the same.”

Then, on 11 December last year came the summons to Redditch magistrates’ court. He consulted a lawyer and pleaded guilty on 15 March. With the fine, his own costs and those of the government, he was £22,800 out of pocket.

This was the decision that so appalled Penrose, the anti-corruption champion. “The only prosecution that has ever been brought was the gentleman who was trying to point out the problem in the first place, and admitted it, and drew it to the authorities’ attention. And what did he get for his pains? A £22,000 [bill],” he said, at the media-focused Frontline Club’s regular kleptoscope event (full disclosure: which I organise and host) in London on Wednesday. “That cannot be right, that has to be wrong. But it rather self-evidently proves the point that we’re not paying enough attention to whether this information is being filed properly and I’ve already taken this up in the last 24 hours with ministers.”

It took me most of a day to discover who had taken the decision to prosecute Brewer. BEIS, the department whose minister, Andrew Griffiths, was so enthusiastic in the original press release, passed me on to Companies House, which credited the decision to unnamed “prosecutors”. A spokesman for the Crown Prosecution Service told me with undisguised relief that the decision had had nothing to do with them. Eventually, the buck stopped with the Insolvency Service, where a spokesman confirmed that they had received a file from Companies House. “The Insolvency Service Prosecutor concluded that there was sufficient evidence to institute criminal proceedings with regards to the Code for Crown Prosecutors and that it was in the public interest to do so,” he said.

The Code for Crown Prosecutors is an 18-page document laying out what to consider before taking someone to court. It is divided into stages and this case would have clearly passed the evidence stage, since Brewer himself had either provided all the evidence needed or else left it in plain sight in the files of Companies House. The public interest stage was a more interesting hurdle to overcome, however, particularly the requirement to consider the “circumstances of the victim”. Who exactly was the victim of Brewer’s crime?

Neville-Rolfe, who had no warning or explanation for what had happened, never met Brewer and didn’t realise it was supposed to be a stunt, said it felt like a violation, almost as if she’d been hacked. Cleverly, however, who had met Brewer and perhaps realised the robust nature of his sense of humour, has confirmed that he sees no reason for Brewer to be prosecuted.

Cable, now leader of the Liberals Democrats, said in a statement that he thought this was an overreaction. “The civil servants were doing their job trying to protect me because they were worried this was a scam. However, in retrospect. this was heavy handed and they did not sufficiently realise that Kevin Brewer was trying to improve the system,” he said. “They should drop the fine.”