Janaki Nair in The Hindu

The rules of worship are made, unmade, and remade over time and Sabarimala is no exception

I remember seeing the ‘birth’ of Ayyappa on stage during a Kathakali performance. Following the drama of Bhasmasura’s destruction by Vishnu as Mohini, Shiva’s fear turning to gratitude, the two ‘male’ gods retreated behind the curtain drawn across the stage. The curtain trembled to the clash and roar of cymbals, drums and singing, before being lowered to reveal an image of Ayyappa. We were overawed by the performance and did not think of raising questions about the ways of the gods. I remember too, in the late 1960s, participating in the ‘kettanara’ rituals (the placing of the bundle of offerings and some items for sustenance on the pilgrim’s head before he sets off on the pilgrimage) of young cousins departing for Sabarimala on foot. The ritual involved all the women in the household. The young men were unshaven, in black, had donned the mala, and were ready to walk the long route barefoot after having observed their 41-day vrathams. I was overawed by the faith of the young ‘Ayyappa’, the women, and was too young to raise any ‘why nots’.

Shortcuts and compromises

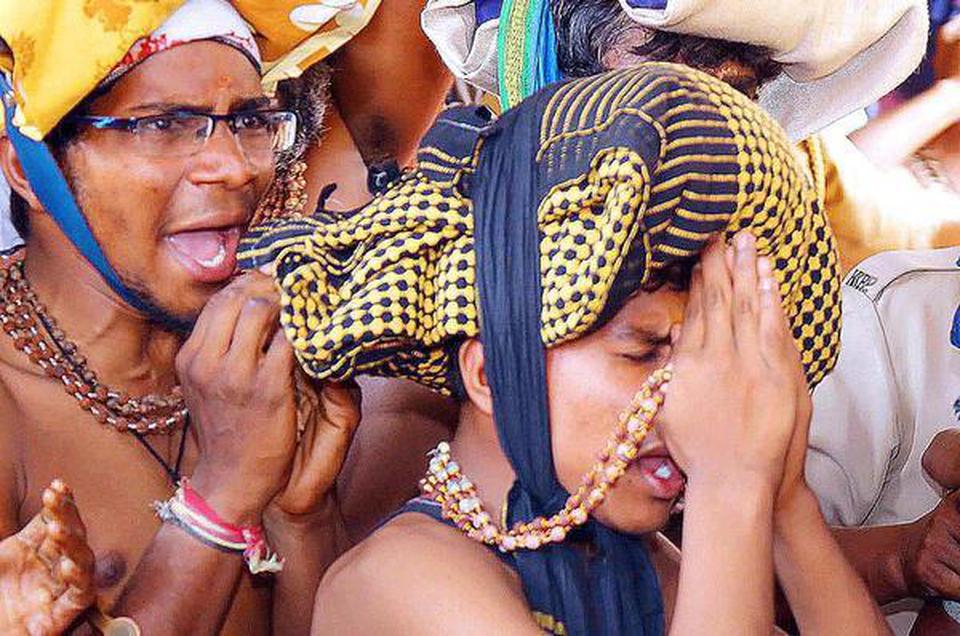

In the 1960s, the young ‘Ayyappa’ would have been among the 15,000 or so who made that arduous journey. No longer. In the past five decades, as the numbers have burgeoned to millions, Lord Ayyappa has been witness to, and extremely tolerant of, every aspect of the pilgrimage being changed beyond recognition. Let us begin with the most important reason being cited for prohibiting women pilgrims of menstruating age: that they cannot maintain the 41-day vratham. Yet, as we know from personal knowledge, and from detailed anthropological studies of this pilgrimage, the shortcuts and compromises on that earlier observance have been many and Lord Ayyappa himself seems to have taken the changes in his stride.

Not all those who reach the foot of the 18 steps that have to be mounted for the darshan of the celibate god observe all aspects of the vratham. A corporate employee, such as one in my family, may observe the restrictions on meat, alcohol and sex, but has given up the compulsion of wearing black or being barefoot. I recall being startled when I saw ‘Ayyappas’ clad in black enjoying a smoke in the corner of the newspaper office where I once worked; I was told that it was only alcohol that was to be abjured. My surprise was greater when I saw several relatives donning the mala about a week before setting off on the pilgrimage, a serious abbreviation of the 41-day temporary asceticism. Though this has meant no diminution in the faith of those visiting the shrine, clearly the pilgrim’s progress has been adapted to the temporalities of modern life.

Lord Ayyappa has surely observed that the longer pedestrian route to his forest shrine has been shortened by the bus route. From 1,29,000 private vehicles in 2000 to 2,65,000 in 2005, not to mention the countless bus trips, this has resulted in intolerable strains on a fragile ecology. In other words, pilgrim tourism, far from being promoted by women’s entry to Sabarimala, had already reached unbearable limits.

One of the most vital practices of this pilgrimage enjoins the pilgrim to carry his own consumption basket: nothing should be available for purchase. Provisions for drinking and cleaning water apart, the sacred geography of the shrine was preserved by such restrictions on consumption. But like many large religious corporations such as Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams, the conveniences of commerce have pervaded every step of the way, with shops selling ‘Ayyapan Bags’ and other ‘ladies’ items’ that can be carried back to the women in the family. In addition to the gilding of the 18 steps, which naturally disallows the quintessential ritual of breaking coconuts, Lord Ayyappa may perhaps have been somewhat amused by the conveyor belt that carries the offerings to be counted. Those devotees who take a ‘return route’ home via Kovalam to relieve the severities of the temporary celibacy would perhaps be pardoned, even by the Lord, as much as by anthropologists who have noted such interesting accretions. And in 2016, according to the Quarterly Current Affairs, the Modi government announced plans to make Sabarimala an International Pilgrim Centre (as opposed to the State government’s request to make it a National Pilgrim Centre) for which funds “would never be a problem”.

The invention of ‘tradition’

Lest this be mistaken for a cynical recounting of the countless ways in which the pilgrimage has been ‘corrupted’, let me hasten to say that my point is far simpler. Anyone who studies the social life and history of religion will recognise that practices are constantly adapted and reshaped, as collectivities themselves are changed, adapted and refashioned to suit the constraints of cash, time or even aesthetics. For this, the historians E.J. Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger coined the term “the invention of tradition”. Who amongst us does not, albeit with a twinge of guilt, agree to the ‘token’ clipping of the hair at Tirupati in lieu of the full head shave? Who does not feel an unmatched pleasure in the piped water that gently washes the feet as we turn the corner into the main courtyard of Tirupati after hours of waiting in hot and dusty halls? And who does not feel frustrated at the not-so-gentle prod of the wooden stick by the guardian who does not allow you more than a few seconds before the deity at Guruvayur? All these belong properly to the invention of ‘tradition’ leaving no practice untouched by the conveniences of mass management.

But perhaps the most important invention of ‘tradition’ was the absolute prohibition of women of menstruating age from worship at Sabarimala under rules 3(b) framed under the Kerala Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorisation of Entry) Act, 1965. Personal testimonies have shown that strict prohibition was not, in fact, always observed, but would such a legal specification have been necessary at all if everyone was abiding by that usage or custom from ‘time immemorial’? It is a “custom with some aberrations” as pointed out by Indira Jaisingh, citing the Devaswom Board’s earlier admission that women had freely entered the shrine before 1950 for the first rice feeding ceremonies of their children.

Elsewhere, the celibate Kumaraswami, in Sandur in Karnataka where women were strictly disallowed, has gracefully conceded space to women worshippers since 1996. “The heavens have not fallen,” Gandhi remarked in 1934 when “a small state in south India [Sandur] has opened the temple to the Harijans.” Lord Ayyappa, who has tolerated innumerable changes in the behaviour of his devotees, will surely not allow his wrath to manifest itself. He will be saddened by the hypermobilisation that surrounds the protests today, but would be far more forgiving than the men — and those women — who make, unmake and remake the rules of worship.