Paul Mason in The Guardian

To stop Jeremy Corbyn, the British elite is prepared to abandon Brexit – first in its hard form and, if necessary, in its entirety. That is the logic behind all the manoeuvres, all the cant and all the mea culpas you will see mainstream politicians and journalists perform this week.

And the logic is sound. The Brexit referendum result was supposed to unleash Thatcherism 2.0 – corporate tax rates on a par with Ireland, human rights law weakened, and perpetual verbal equivalent of the Falklands war, only this time with Brussels as the enemy; all opponents of hard Brexit would be labelled the enemy within.

But you can’t have any kind of Thatcherism if Corbyn is prime minister. Hence the frantic search for a fallback line. Those revolted by the stench of May’s rancid nationalism will now find it liberally splashed with the cologne of compromise.

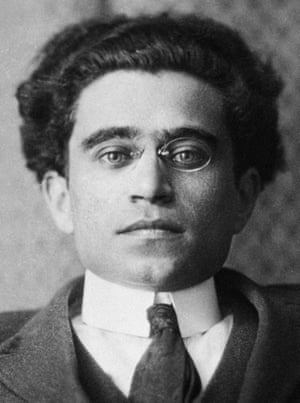

Labour has, quite rightly, tried to keep Karl Marx out of the election. But there is one Marxist whose work provides the key to understanding what just happened. Antonio Gramsci, the Italian communist leader who died in a fascist jail in 1937, would have had no trouble understanding Corbyn’s rise, Labour’s poll surge, or predicting what happens next. For Gramsci understood what kind of war the left is fighting in a mature democracy, and how it can be won.

Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist theoretician and politician. Photograph: Laski Diffusion/Getty Images

Consider the events of the past six weeks a series of unexpected plot twists. Labour starts out polling 25% but then scores 40%. Its manifesto is leaked, raising major questions of competence, but it immediately boosts Corbyn’s popularity. Britain is attacked by terrorists but it is the Tories whose popularity dips. Diane Abbott goes sick – yet her majority rises to 30,000. Sitting Labour candidates campaign on the premise “Corbyn cannot win” yet his presence delivers a 10% boost to their own majorities.

None of it was supposed to happen. It defies political “common sense”. Gramsci was the first to understand that, for the working class and the left, almost the entire battle is to disrupt and defy this common sense. He understood that it is this accepted common sense – not MI5, special branch and the army generals – that really keeps the elite in power.

Once you accept that, you begin to understand the scale of Corbyn’s achievement. Even if he hasn’t won, he has publicly destroyed the logic of neoliberalism – and forced the ideology of xenophobic nationalist economics into retreat.

Brexit was an unwanted gift to British business. Even in its softest form it means 10 years of disruption, inflation, higher interest rates and an incalculable drain on the public purse. It disrupts the supply of cheap labour; it threatens to leave the UK as an economy without a market.

But the British ruling elite and the business class are not the same entity. They have different interests. The British elite are in fact quite detached from the interests of people who do business here. They have become middle men for a global elite of hedge fund managers, property speculators, kleptocrats, oil sheikhs and crooks. It was in the interests of the latter that Theresa May turned the Conservatives from liberal globalists to die-hard Brexiteers.

The hard Brexit path creates a permanent crisis, permanent austerity and a permanent set of enemies – namely Brussels and social democracy. It is the perfect petri dish for the fungus of financial speculation to grow. But the British people saw through it. Corbyn’s advance was not simply a result of energising the Labour vote. It was delivered by an alliance of ex-Ukip voters, Greens, first-time voters and tactical voting by the liberal centrist salariat.

The alliance was created in two stages. First, in a carefully costed manifesto Corbyn illustrated, for the first time in 20 years, how brilliant it would be for most people if austerity ended and government ceased to do the work of the privatisers and the speculators. Then, in the final week, he followed a tactic known in Spanish as la remontada – the comeback. He stopped representing the party and started representing the nation; he acted against stereotype – owning the foreign policy and security issues that were supposed to harm him. Day by day he created an epic sense of possibility.

The ideological results of this are more important than the parliamentary arithmetic. Gramsci taught us that the ruling class does not govern through the state. The state, Gramsci said, is just the final strongpoint. To overthrow the power of the elite, you have to take trench after trench laid down in their defence.

Last summer, during the second leadership contest, it became clear that the forward trench of elite power runs through the middle of the Labour party. The Labour right, trained during the cold war for such trench warfare, fought bitterly to retain control, arguing that the elite would never allow the party to rule with a radical left leadership and programme.

The moment the Labour manifesto was leaked, and support for it took off, was the moment the Labour right’s trench was overrun. They retreated to a second trench – not winning, with another leadership election to follow – but that did not exactly go well either.

As to the third trench line – the tabloid press and its broadcasting echo chamber – this too proved ineffectual. More than 12 million people voted for a party stigmatised as “backing Britain’s enemies”, soft on terror, with “blood on its hands”.

None of it was supposed to happen. It defies political “common sense”. Gramsci was the first to understand that, for the working class and the left, almost the entire battle is to disrupt and defy this common sense. He understood that it is this accepted common sense – not MI5, special branch and the army generals – that really keeps the elite in power.

Once you accept that, you begin to understand the scale of Corbyn’s achievement. Even if he hasn’t won, he has publicly destroyed the logic of neoliberalism – and forced the ideology of xenophobic nationalist economics into retreat.

Brexit was an unwanted gift to British business. Even in its softest form it means 10 years of disruption, inflation, higher interest rates and an incalculable drain on the public purse. It disrupts the supply of cheap labour; it threatens to leave the UK as an economy without a market.

But the British ruling elite and the business class are not the same entity. They have different interests. The British elite are in fact quite detached from the interests of people who do business here. They have become middle men for a global elite of hedge fund managers, property speculators, kleptocrats, oil sheikhs and crooks. It was in the interests of the latter that Theresa May turned the Conservatives from liberal globalists to die-hard Brexiteers.

The hard Brexit path creates a permanent crisis, permanent austerity and a permanent set of enemies – namely Brussels and social democracy. It is the perfect petri dish for the fungus of financial speculation to grow. But the British people saw through it. Corbyn’s advance was not simply a result of energising the Labour vote. It was delivered by an alliance of ex-Ukip voters, Greens, first-time voters and tactical voting by the liberal centrist salariat.

The alliance was created in two stages. First, in a carefully costed manifesto Corbyn illustrated, for the first time in 20 years, how brilliant it would be for most people if austerity ended and government ceased to do the work of the privatisers and the speculators. Then, in the final week, he followed a tactic known in Spanish as la remontada – the comeback. He stopped representing the party and started representing the nation; he acted against stereotype – owning the foreign policy and security issues that were supposed to harm him. Day by day he created an epic sense of possibility.

The ideological results of this are more important than the parliamentary arithmetic. Gramsci taught us that the ruling class does not govern through the state. The state, Gramsci said, is just the final strongpoint. To overthrow the power of the elite, you have to take trench after trench laid down in their defence.

Last summer, during the second leadership contest, it became clear that the forward trench of elite power runs through the middle of the Labour party. The Labour right, trained during the cold war for such trench warfare, fought bitterly to retain control, arguing that the elite would never allow the party to rule with a radical left leadership and programme.

The moment the Labour manifesto was leaked, and support for it took off, was the moment the Labour right’s trench was overrun. They retreated to a second trench – not winning, with another leadership election to follow – but that did not exactly go well either.

As to the third trench line – the tabloid press and its broadcasting echo chamber – this too proved ineffectual. More than 12 million people voted for a party stigmatised as “backing Britain’s enemies”, soft on terror, with “blood on its hands”.

And Gramsci would have understood the reasons here, too. When most socialists treated the working class as a kind of bee colony – pre-programmed to perform its historical role – Gramsci said: everyone is an intellectual. Even if a man is treated as “trained gorilla” at work, outside work “he is a philosopher, an artist, a man of taste ... has a conscious line of moral conduct”. [Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks]

On this premise, Gramsci told the socialists of the 1930s to stop obsessing about the state – and to conduct a long, patient trench warfare against the ideology of the ruling elite.

Eighty years on, the terms of the battle have changed. Today, you do not need to come up from the mine, take a shower, walk home to a slum and read the Daily Worker before you can start thinking. As I argued in Postcapitalism, the 20th-century working class is being replaced as the main actor – in both the economy and oppositional politics – by the networked individual. People with weak ties to each other, and to institutions, but possessing a strong footprint of individuality and rationalism and capacity to act.

What we learned on Friday morning was how easily such networked, educated people can see through bullshit. How easily they organise themselves through tactical voting websites; how quickly they are prepared to unite around a new set of basic values once someone enunciates them with cheerfulness and goodwill, as Corbyn did.

The high Conservative vote, and some signal defeats for Labour in the areas where working class xenophobia is entrenched, indicate this will be a long, cultural war. A war of position, as Gramsci called it, not one of manoeuvre.

But in that war, a battle has been won. The Tories decided to use Brexit to smash up what’s left of the welfare state, and to recast Britain as the global Singapore. They lost. They are retreating behind a human shield of Orange bigots from Belfast.

The left’s next move must eschew hubris; it must reject the illusion that with one lightning breakthrough we can envelop the defences of the British ruling class and install a government of the radical left.

The first achievable goal is to force the Tories back to a position of single-market engagement, under the jurisdiction of the European court of justice, and cross-party institutions to guide the Brexit talks. But the real prize is to force them to abandon austerity.

A Tory party forced to fight the next election on a programme of higher taxes and increased spending, high wages and high public investment would signal how rapidly Corbyn has changed the game. If it doesn’t happen; if the Conservatives tie themselves to the global kleptocrats instead of the interests of British business and the British people, then Corbyn is in Downing Street.

Either way, the accepted common sense of 30 years is over.