|

| Laxman and Dravid "dissolved into one another more harmoniously, more significantly, than any other Indian duo" © AFP |

| Enlarge

|

|

|

|

"Nusrat singing, Laxman and Dravid batting - TV on mute, and yoga." A note from an acquaintance in Mumbai had this description of his perfect day. Rahul Dravid and V. V. S. Laxman marked their Test debuts within six months of one another in 1996 with accomplished half-centuries. Sixteen years later they announced their retirements in accomplished press conferences, also within six months of each other. But this note came not on the occasion of a batting feat or a retirement. It was, in Indian shorthand, an ode to long-form cricket - and the pair that most profoundly summoned its sensation.

Consider the correspondent's other passions. A partnership of Laxman and Dravid could contain both the incantatory rapture of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and the meditative discipline of yoga. One might say Laxman was the rapture and Dravid the discipline, but that would not only be partially false, it would be to miss the point. The beauty of a jugalbandi, a duet between classical soloists, is in the interplay. A jugalbandi is a duet in the same way as a batting partnership: not simultaneous, but one performer at a time, in improvisatory rotation. The great sitar player Ustad Vilayat Khan said the idea was to both showcase and subdue oneself. As he hands over to his partner, the artist must judge how much to dissolve the tune. Dravid and Laxman dissolved into one another more harmoniously, more significantly, than any other Indian duo.

Separately, theirs were brilliant careers. Dravid's was colossal. He played 164 Tests, faced more deliveries than anyone in history (31,260), and made more runs (13,288) than all but two. He became the first man to 200 catches, most of them snaffled at first slip. For a supposed misfit in one-day internationals, he still racked up over 10,000 runs at nearly 40. Though he enjoyed neither, he kept wicket or opened the innings with courage and competence, whenever needed. In a tumultuous stint as captain, he oversaw a first-round World Cup exit and Test series victories in the West Indies and England.

Laxman, who when picked for India still hadn't ruled out returning to medical studies to become a doctor like his parents, scored close to 9,000 runs in 134 Tests. Against Australia, the premier team of the era, he struck ten sublime international centuries, including one that may just be the greatest innings in all cricket. Like Dravid, he caught well at bat-pad, then in the slips. Sometimes vice-captain, he was seen by younger team-mates as the avuncular bridge between generations. They called himmama, or uncle. These are the bare facts.

Part of their harmony was that Laxman and Dravid were similar and dissimilar in equal measure. They were both from southern India - Laxman from Hyderabad, Dravid from Bangalore - and were both gentlemen (south Indians will think this a tautology). Raised on matting wickets, they enjoyed bounce and back-foot play. They were tall, wristy, hit the ball along the ground, and possessed what cricket watchers refer to as "temperament".

For all that, they could give off very different impressions: Dravid seemed to care a little too much, Laxman not enough. This may be because Dravid perspired heavily and tended to grimace, whereas Laxman looked always a serene stroller in pleasant climes. It may be because Dravid committed himself to sincere footwork, whereas Laxman (against pace) trusted his hands and the curvy abstractions of what he once told me was his "bat flow".

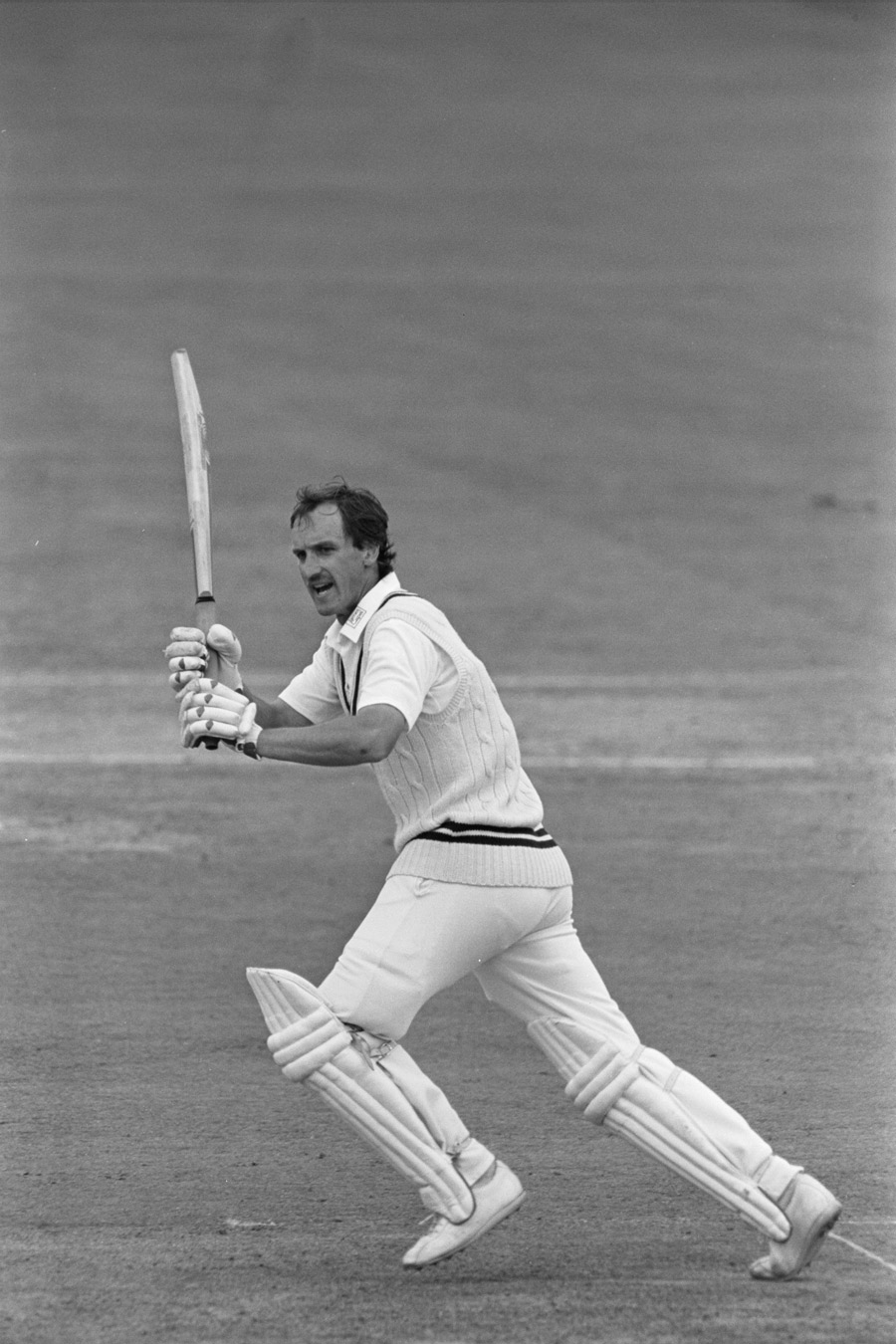

Sporting impressions are rarely false. It's just that sportswriters, like cartoonists, exaggerate the features. As with David Gower, the game looked easy in Laxman's lovely hands. He was Goweresque in only that respect. He was not to be spotted swooping in a biplane over his team-mates, or sozzled at an official reception. He was a diligent man, who worked all career at ironing out any incriminating casualness from his strokes; a religious man, who can quote verses from the Bhagavad Gita, and in the early years could be seen muttering a prayer (to the saint Sai Baba) as he faced up.

Meanwhile Dravid, given to over-intensity, honed relaxation into a fine art. Before matches, he willed himself away from self-torture through video analysis and training sessions, to long lunches, long sleep, and slow living. Waiting to bat, he watched the game only briefly. He was no contest, it is true, for Laxman, who was fond of showering when the man before him went in, and thereafter might be found lying under a table listening to music on headphones.

When his turn arrived, Dravid strode out briskly to the centre. On certain days, with chest and arm guards in place, his back erect and knees high for a man with pads, it could be said he marched out. Laxman appeared sometimes belatedly, somewhat gingerly (bad knees), with a pacific, Mona Lisa quasi-smile, and collar turned up in the Hyderabadi way. At the crease they were calm, immersed in their work like artistes. They were happy to bat for hours, days. Occasionally Dravid responded to sledging, though in an upstanding kind of manner. Laxman seemed not to notice at all. While fielding in the slips they talked to each other, Dravid told journalist Nagraj Gollapudi, "about kids, house construction, plumbers, electricians, running errands".

The mammoth partnership has usually been the preserve of those in successive batting positions. Only seven pairs in Test history have put together two or more triple-century stands, as Dravid and Laxman did. These have been either openers - Herschelle Gibbs and Graeme Smith - or batted close together: Bill Ponsford and Don Bradman, Kumar Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene, Younis Khan and Mohammad Yousuf, Hashim Amla and Jacques Kallis, Ricky Ponting and Michael Clarke. But Dravid and Laxman batted at opposite poles of the middle order, at first drop and fourth. Three-hundred-and-something runs for the fifth wicket suggests more than appetite: it suggests valour.

Valour was scarce in the times we refer to. To understand Indian cricket at the turn of the century, consider the sequence: clean-swept in Australia, clean- swept at home by South Africa, the resignation of a deflated captain (Sachin Tendulkar), the naming of the previous captain (Mohammad Azharuddin) and several players in a match-fixing scandal. To passionate fans, cricket felt desperate; to others, it felt wholly discredited.

Kolkata, 2001: it was a day short of the Ides of March. But the 14th was no less portentous for Australia's Caesar, Steve Waugh. On that day two years previously, a beleaguered West Indies side had risen again in Kingston: from 37 for four overnight, Brian Lara and Jimmy Adams batted almost all day and overturned a series. Australia had advanced since, revivified by the phenomenon of Adam Gilchrist, the tank-sniper combination of Matthew Hayden and Justin Langer, and Waugh's own ruthless ambition. Forget losses: they barely did draws. Going into Kolkata they had racked up a world record 16 straight Test wins. The latest of those was a three-day demolition of India in Mumbai. And in Kolkata, a quartet of Glenn McGrath, Jason Gillespie, Michael Kasprowicz and Shane Warne had bowled Australia to a 274-run lead.

|

| Kolkata 2001: "batting, and batting, and more beautiful batting" © AFP |

| Enlarge

|

|

|

The rest is an Indian fairytale: Laxman the last man out in the first innings for a dashing 59, asked to keep his pads on by his captain and the coach, swapping positions with a struggling Dravid in the follow-on, the two coming together in the second innings with Laxman almost upon his century but India still behind Australia's first-innings total.

And then the batting, and batting, and more beautiful batting, over a short evening, the whole of March 14, and then some more. Laxman curling the ball through imperceptible gaps, Dravid regaining lost form through pure unblinking will, Laxman now flick-pulling the fast bowlers as if tossing frisbees, now driving them on the rise, sinuous jabs that raced improbably across the big green outfield, Dravid now blocking, now shouldering arms, now leaning back to cut, the old sureness slowly redeveloping, Laxman inside-outing Warne miraculously from far outside leg stump, now whipping him against the turn, Dravid, fully restored, emboldened to come down the track himself and wrist Warne across his break, all of this in the huge sound and growing belief of a hundred thousand in Eden Gardens, an energy that must be experienced to be understood.

Laxman batted ten and a half hours for 281. Dravid was run out for 180 after nearly seven and a half. Together they put on 376. These were runs made in some discomfort: Laxman had been listing, much like a ship, and his back had to be realigned by the physio during the intervals; Dravid, battling the high humidity of Kolkata and his own rate of perspiration, cramped with dehydration. Around their necks both wore strips of towel drenched in ice-water, and they returned to a dressing-room installed with drips. India won the Test, magically, then the series. If a virtue of sport is to make a people cast aside their troubles, not by fantasy but aspiration, here it was.

Three seasons on, the Indian team were finding their way in the world - but not yet in Australia. At Adelaide, they were 85 for four, trailing by 471, doomed to a ritual humiliation. Despite the absence of Warne and McGrath, the task didn't look hard: it looked hopeless. India hadn't won a Test in Australia for 23 years. Of the 26 Tests that Steve Waugh had captained at home, Australia had won 21 and lost one (a dead rubber in the 2002-03 Ashes). Soon the familiar chemistry between our like-and-unlike couple began to galvanise into something close to inevitability.

Here, Dravid played the lead. He was back at No. 3, and in the form of his life. The previous year he had hit Test centuries in four successive innings, three of them in England, including a defensive tour de force at Headingley. Sunny Adelaide allowed him to be more expansive. His handsomest stroke, the front-foot drive through cover, he repeatedly demonstrated, bending low on his left knee like a skater and letting his arms arc out. Astonishingly, he brought up his century with a miscued pull - for six. He even surprised himself when, late in the collaboration, he looked at the scoreboard to find he had outscored his partner. "Yeah, jeez, not bad for a blocker, huh?" he told the sportswriter Rohit Brijnath.

This time they put on 303: Laxman 148, Dravid 233. In a neat inversion, as Laxman had set up Kolkata with a first-innings fifty, here Dravid anchored a hard fourth-innings chase with 72 not out. When he cut the winning runs to the boundary, Waugh made a point of retrieving the ball from the gutter and handing it over. Waugh retired after the series, and to write a foreword to his autobiography he invited Dravid, a much younger man who had once sought him out to ask how to take his game to a higher plane.

There was much more to Dravid and Laxman than these two partnerships - and also, of course, often much less. Laxmanophiles were bewildered that a batsman of his calibre should average so far below 50, appalled (and secretly charmed) by his running between the wickets, and plain frustrated when the ball seamed about and he poked to slip; against England he averaged 30. Likewise, Dravid partisans could try to construct defences for his unflattering averages against Australia and South Africa, the best bowling attacks of the time - but how to enjoy his most tuneless offerings, the 16-off-114-balls variety, except by wilful perversity? (Dravid, who had not just the cussedness but also the humour to perpetrate these innings, once raised his bat to applause from an Australian crowd after a single.)

Indians place on a pedestal the twin epics because of what they were, and also because of their associations. To think of Dravid's 233 at Adelaide is also to think of his monumental 270 in Rawalpindi, 148 at Headingley, or 93 at Perth - all setting up ground-breaking overseas victories. To think of Laxman's Kolkata masterpiece is also an oblique tribute to its younger brothers: from late 2010 alone, extraordinary fourth-innings chases against Australia and Sri Lanka, and a third-innings 96 in Durban when nobody else in the match touched 40.

Team success cannot and should never be a necessary or a sufficient condition for a cricketer's accomplishments, but in the Indian instance it felt urgent. The Indian side of the 2000s was up against a history of flickering achievement amid lethargic underperformance. Of the batting line-up instrumental in overturning that history, Dravid was the spine and Laxman the nerve. Their runs were tough, elegant and vital. Their manner was classic. The echoes of Kolkata and Adelaide rang down the decade, in far-flung venues and memories, and in notes from cricket watchers to one another.