There are some names that, as a young cricketer, you do not want, because they come loaded with a heavy freight. They are almost always familial. Imagine the task of clambering clear of the moniker of Botham or Richards as Liam and Mali once had to do. The Don's son briefly changed his, so distorting was its effect on his life. They are names that do not stand simply for cricketers of note, but for something bigger: a way of playing the game itself.

Imagine then, that you are William Tavaré, who has signed a contract to play professional cricket for Gloucestershire. Because as surely as Botham, Richards or Bradman are names that come laden with meaning, then so is Tavaré. William is the nephew of perhaps the most extraordinary batsman to appear for England in the last 30 years, the motionless phenomenon that was CJ Tavaré.

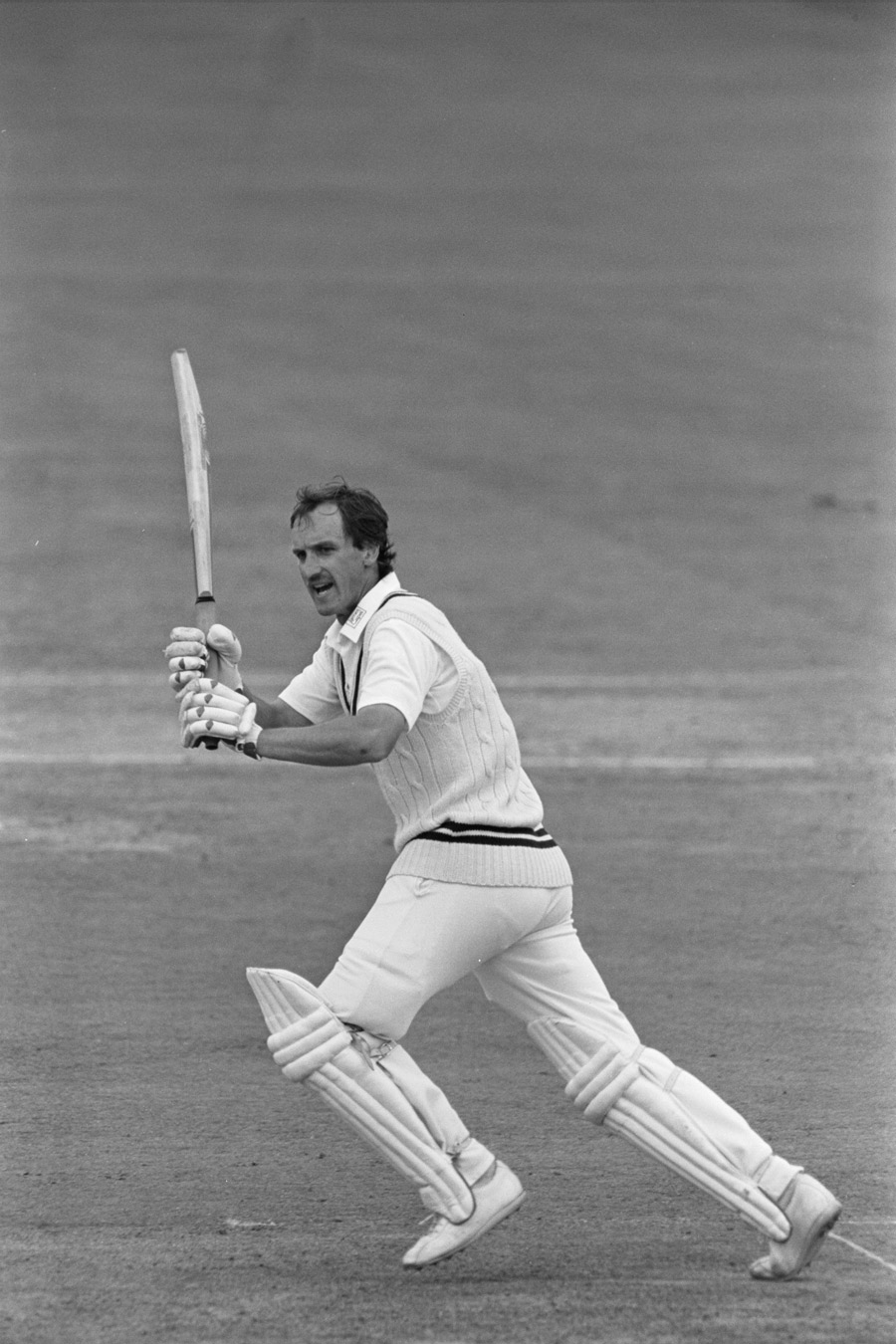

No one who saw Chris Tavaré bat will forget it in a hurry, even if the detail is blurred by its endless repetition. If David Steele was the bank clerk who went to war, Tavaré was the conscientious objector who took arms. Tall, angular and splayfooted, a thin moustache sketched on his top lip, he would walk to the crease like a stork approaching a watering hole full of crocs.

Once there, he began not to bat but to set, concrete drying under the sun. His principal movement was between the stumps and square leg, to where he would walk, gingerly, after every ball. If John Le Mesurier had played Test cricket, he would have played it like Chris Tavaré. His innings spread themselves across games, eroding the will of the opposition and the spectator alike, smoothing off the edges as if they were pebbles in a stream.

The portents came early. In his third Test innings, against West Indies at Lord's in 1980, he fussed for more than four hours over 42. In his next game, his 69 and 78 combined to occupy just under 12 hours of playing time.

Then came the innings that cemented (almost literally) his legend. His four-hour-plus fifty against Pakistan in 1982 was the second-slowest half-century in the history of the game, and yet even that paled in comparison to the five-and-a-half hour 35 against India in Madras, a knock that assumed the dimensions of a siege for all involved.

In a team that contained Botham, Gatting, Lamb and Gower, Tavaré truly stood out. The mighty ballast that he provided against the Australians in '81 (179 runs at 44.75) played a part in that famous win, albeit one that never quite makes the highlights reels.

His only Ashes tour in 1982-83 left its scars on the local psyche, too. As Matthew Engel slyly noted, "he was the antithesis of the Australians' idea of a cricketer". In Perth, he treated them to an eight-hour 89, 60 minutes of which were entirely scoreless. Gideon Haigh fell into a trance-like state while watching it on television, and later discovered that Tavaré (a uxorious gent, of course) had been troubled all tour by his wife's fear of flying, a mental trauma that nailed him ever more firmly to the crease.

Like a lot of slow players, stories abounded that he was a wolf in sheep's clothing, capable of pillaging county attacks on quiet Canterbury afternoons. If it happened, no one remembers it now. Instead, his high point as a man of action must remain the classic fourth Test, in Melbourne, that began, on Boxing Day of 1982, with Tav making 89 in just 247 minutes at a strike rate north of three an over, an innings that contained 15 boundaries in an era when the distant reaches of the MCG were marked only by the pickets. It was his anomalous masterpiece, and England won by three runs.

Rather marvellously, Chris Tavaré is now a biology teacher, and his pupils are surely rigorously but gently schooled. Into a cricketing world that he would not recognise steps William, whose first-class record to date is respectable (nine innings at 32.75, with a best of 61), but even if he turns out to be the next Chris Gayle, the Tavaré name will plod after him - slowly and from a distance of course. Good luck, my friend.

No comments:

Post a Comment