'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 19 December 2021

Friday, 17 December 2021

Tuesday, 14 December 2021

Friday, 10 December 2021

Spending without taxing: now we’re all guinea pigs in an endless money experiment

No government has openly embraced modern monetary theory, but many of the radical doctrine’s core principles are informing today’s policy decisions writes Satyajit Das in The Guardian

‘A state, MMT argues, finances its spending by creating money, not from taxes or borrowing. As nations cannot go bankrupt when they can can print their own currency, deficits and debt don’t matter.’ Photograph: RBA/PR IMAGE

Today, citizens are unwitting participants in a covert policy experiment. It embraces the idea of higher government spending without the necessity of increased taxes. While modern monetary theory (MMT), the doctrine, has obvious appeal for politicians, irrespective of economic religion, the long-term consequences may prove problematic.

A state, MMT argues, finances its spending by creating money, not from taxes or borrowing. As nations cannot go bankrupt when they can print their own currency, deficits and debt don’t matter. Accordingly, governments should spend to ensure full employment, guaranteeing a job for everyone willing to work. Alternatively, though not formally part of MMT, governments can fund universal basic income (UBI) schemes, providing every individual an unconditional flat-rate payment irrespective of circumstances.

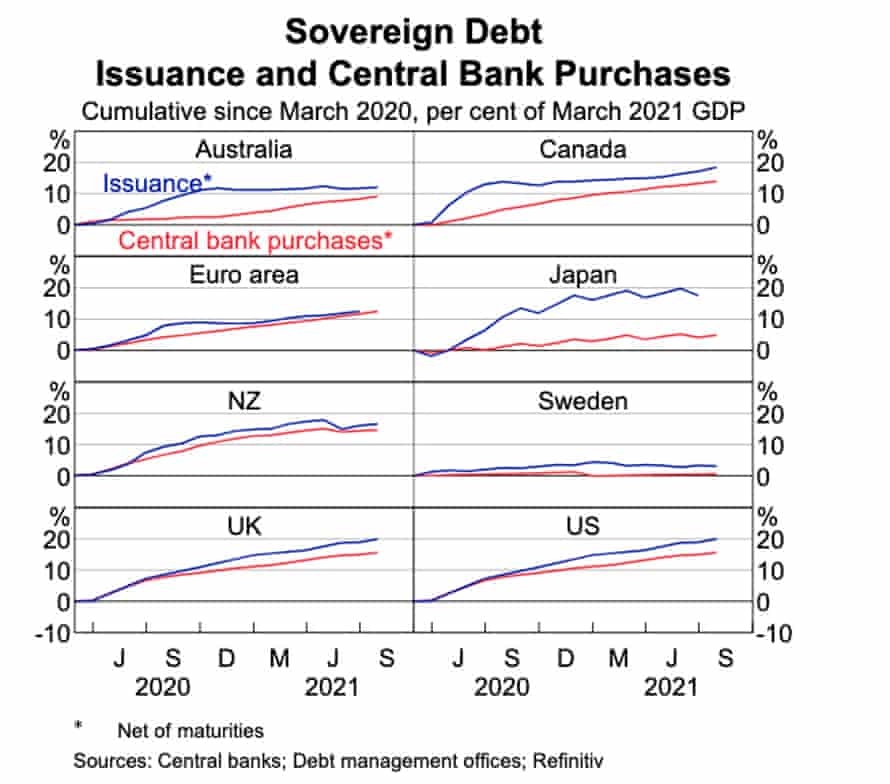

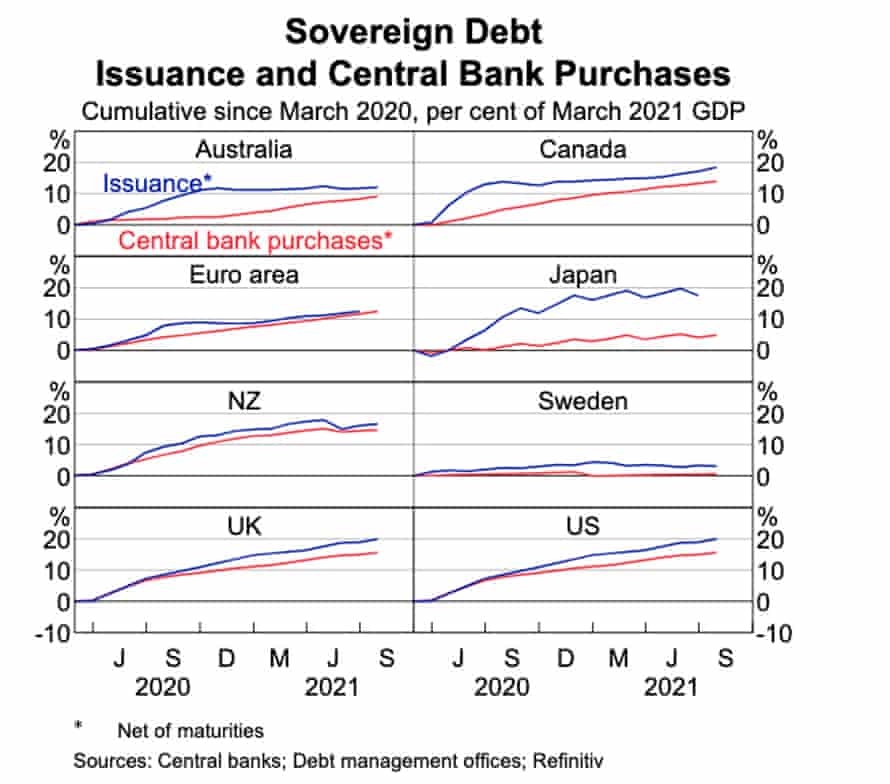

While no government or central bank overtly advocates MMT, since the 2008 global financial crisis and, more recently, the pandemic, policymakers have adopted many of its tenets by stealth. Popular one-off payments and increased welfare entitlements, which could become permanent, increasingly support economic activity. As the graph below highlights, central banks now buy a high percentage of new government debt, effectively financing this additional spending by money creation.

Today, citizens are unwitting participants in a covert policy experiment. It embraces the idea of higher government spending without the necessity of increased taxes. While modern monetary theory (MMT), the doctrine, has obvious appeal for politicians, irrespective of economic religion, the long-term consequences may prove problematic.

A state, MMT argues, finances its spending by creating money, not from taxes or borrowing. As nations cannot go bankrupt when they can print their own currency, deficits and debt don’t matter. Accordingly, governments should spend to ensure full employment, guaranteeing a job for everyone willing to work. Alternatively, though not formally part of MMT, governments can fund universal basic income (UBI) schemes, providing every individual an unconditional flat-rate payment irrespective of circumstances.

While no government or central bank overtly advocates MMT, since the 2008 global financial crisis and, more recently, the pandemic, policymakers have adopted many of its tenets by stealth. Popular one-off payments and increased welfare entitlements, which could become permanent, increasingly support economic activity. As the graph below highlights, central banks now buy a high percentage of new government debt, effectively financing this additional spending by money creation.

Sovereign Debt Issuance and Central Bank purchases. Photograph: Reserve Bank of Australia

Source: Nick Baker, Marcus Miller and Ewan Rankin (2021 September) Government Bond Markets in Advanced Economies During the Pandemic; Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin

MMT is actually a melange of old ideas: Keynesian deficit spending; the post gold standard ability of nations to create money at will; and quantitative easing (central bank financed government spending) pioneered by Japan. However, there are several concerns about MMT.

First, the source of useful, well-compensated work is unclear. While MMT suggests taxes can be used to direct production, government influence over businesses that create jobs is limited. The impact of labour-reducing technology and competitive global supply chains is glossed over. Getting one person to dig a hole and another to fill it in creates employment, but it is of doubtful economic and social value. The woeful record of postwar centrally planned economies, where people pretended to work and the government pretended to pay them, highlights the issues.

Second, excess government spending and large deficits financed by money creation risk creating inflation. MMT argues that this is a risk only where the economy is at full employment or there is no excess capacity, and can be managed by fine-tuning intervention.

Third, MMT may weaken the currency. Roughly half of Australia’s government and significant amounts of state, bank and business debt is held by foreigners. Devaluation and loss of investor confidence in the stability of the exchange rate would affect the ability to and cost of borrowing overseas and importing goods. The expense of servicing foreign currency debt would rise.

Fourth, while available to nation states able to issue their own fiat currencies, it is unavailable to state governments, private businesses or households who are major borrowers in Australia.

Fifth, who decides the target employment rate or UBI payment level? Unemployment, inflation and output gaps are difficult to accurately measure in practice. Effects on employment incentives, workforce participation and productivity are untested. How will policymakers control the process or what would happen if MMT failed?

The theory delegates management of MMT operations to politicians, rather than unelected economic mandarins. But financially challenged elected representatives may be poorly equipped for the task. Political considerations and cronyism may influence decisions.

Sixth, there are implications for financial stability. Lower rates, the result of central bank debt purchases, and inflation fears might drive a switch to real assets, increasing the price of property and shares representing claims on underlying cashflows. It may encourage hoarding of commodities. This exacerbates inequality and increases the cost of essentials such as food, fuel and shelter. Fear of debasement of the value of paper money, in part, is behind unproductive speculation in gold and cryptocurrencies.

Seventh, MMT might undermine trust in the currency. Instead of spending the payments, citizens may question a world where governments print money and throw it out of helicopters.

Finally, Japan’s use of persistent deficits to boost short-term economic activity and incur government debt (currently more than 260% of GDP, compared with a global average of about 100%) does not prove the effectiveness of MMT. The country’s circumstances are unique and it has been mired in stagnation for three decades with its GDP largely unchanged.

MMT’s allure is the irresistible promise of freebies; full employment, unlimited higher education, healthcare and government services, state-of-the-art infrastructure, green energy and “the colonisation of Mars”. But monetary manipulation cannot change the supply of real goods and services or overcome resource constraints, otherwise prosperity and utopia would be guaranteed.

While the current game can and will continue for a time, the bill will eventually arrive. The borrowings will have to be paid for out of disposable income, higher taxes or through inflation, which reduces purchasing power, especially of the most vulnerable, and destroys savings. Other than nature’s free bounty, everything has a cost.

Source: Nick Baker, Marcus Miller and Ewan Rankin (2021 September) Government Bond Markets in Advanced Economies During the Pandemic; Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin

MMT is actually a melange of old ideas: Keynesian deficit spending; the post gold standard ability of nations to create money at will; and quantitative easing (central bank financed government spending) pioneered by Japan. However, there are several concerns about MMT.

First, the source of useful, well-compensated work is unclear. While MMT suggests taxes can be used to direct production, government influence over businesses that create jobs is limited. The impact of labour-reducing technology and competitive global supply chains is glossed over. Getting one person to dig a hole and another to fill it in creates employment, but it is of doubtful economic and social value. The woeful record of postwar centrally planned economies, where people pretended to work and the government pretended to pay them, highlights the issues.

Second, excess government spending and large deficits financed by money creation risk creating inflation. MMT argues that this is a risk only where the economy is at full employment or there is no excess capacity, and can be managed by fine-tuning intervention.

Third, MMT may weaken the currency. Roughly half of Australia’s government and significant amounts of state, bank and business debt is held by foreigners. Devaluation and loss of investor confidence in the stability of the exchange rate would affect the ability to and cost of borrowing overseas and importing goods. The expense of servicing foreign currency debt would rise.

Fourth, while available to nation states able to issue their own fiat currencies, it is unavailable to state governments, private businesses or households who are major borrowers in Australia.

Fifth, who decides the target employment rate or UBI payment level? Unemployment, inflation and output gaps are difficult to accurately measure in practice. Effects on employment incentives, workforce participation and productivity are untested. How will policymakers control the process or what would happen if MMT failed?

The theory delegates management of MMT operations to politicians, rather than unelected economic mandarins. But financially challenged elected representatives may be poorly equipped for the task. Political considerations and cronyism may influence decisions.

Sixth, there are implications for financial stability. Lower rates, the result of central bank debt purchases, and inflation fears might drive a switch to real assets, increasing the price of property and shares representing claims on underlying cashflows. It may encourage hoarding of commodities. This exacerbates inequality and increases the cost of essentials such as food, fuel and shelter. Fear of debasement of the value of paper money, in part, is behind unproductive speculation in gold and cryptocurrencies.

Seventh, MMT might undermine trust in the currency. Instead of spending the payments, citizens may question a world where governments print money and throw it out of helicopters.

Finally, Japan’s use of persistent deficits to boost short-term economic activity and incur government debt (currently more than 260% of GDP, compared with a global average of about 100%) does not prove the effectiveness of MMT. The country’s circumstances are unique and it has been mired in stagnation for three decades with its GDP largely unchanged.

MMT’s allure is the irresistible promise of freebies; full employment, unlimited higher education, healthcare and government services, state-of-the-art infrastructure, green energy and “the colonisation of Mars”. But monetary manipulation cannot change the supply of real goods and services or overcome resource constraints, otherwise prosperity and utopia would be guaranteed.

While the current game can and will continue for a time, the bill will eventually arrive. The borrowings will have to be paid for out of disposable income, higher taxes or through inflation, which reduces purchasing power, especially of the most vulnerable, and destroys savings. Other than nature’s free bounty, everything has a cost.

Thursday, 9 December 2021

Who will apologise for plasma therapy? It was a disaster for Covid-19, govt hospitals knew

Hospitals shelved ICMR's reports that plasma therapy wasn't good. It was still rolled out, and people paid the price writes DR KABIR SARDANA in The Print

Plasma therapy was administered to Covid-19 patients during the second wave in India | Wikipedia

Plasma therapy was administered to Covid-19 patients during the second wave in India | Wikipedia

The closing pages of the 18th-century masterpiece fiction The Story of the Stone revealed the essence of the Tao’s message. In Lao Tzu’s words, it means that “Things are not as they seem, that the Eloquent may Stammer, that Perfection may seem Flawed, that Truth is Fiction, Fiction Truth.”

The truth is neither black nor white, it’s grey—the handling of the second wave of Covid-19 is a testimony to that fact.

Disaster that escaped public eye

In the midst of the second wave of Covid-19 with panic all around, a lot of therapeutic disasters were played out, and without a doubt, they were inspired by a lack of knowledge. Instead, they were fueled with a desire for one-upmanship and copycat fame. Some of the doctors unwittingly orchestrated this therapeutic mess. On one side, we had the armchair experts who were not running Covid-19 centres and had shut down their institutes. On the other, doctors in central government hospitals like the Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in Delhi were running Out Patient Departments (OPDs) and wards. They were possibly following half-baked regimens with little proof, as there were lives at stake.

While some medications were possibly harmless and cheap like Ivermectin or HCQS, the others were ridiculously expensive, and no one was wiser about their efficacy. One of them was plasma therapy. Of course, the Indian medical system and healthcare did not have the time for a randomised trial to test a placebo. But the origin of the mess was thus created right here in the capital of the country.

One may ask—who would be the expert to decide on its efficacy? The clear answer is a clinician in a hospital, handling patients with an active plasma extraction centre. But what transpired is that a centre dedicated to liver care with nil experience in Covid-19 treatment proposed the idea that plasma might help. Then came the now-famous statement of Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, saying that Delhi opened the first plasma bank in the world. That set off a chain reaction, and within a few weeks, hospitals followed suit.

It wasn’t the solution

Plasma is a component of the blood that is believed to have antibodies to diseases. Here, it was believed that Covid-19 patients would benefit from such therapy. This was when even the use of Intravenous immunoglobulin (IV IgG), a related plasma-based therapy that had been available for years, wasn’t effective in most disorders. This was also when we all knew that the so-called antibody tests of Covid-19 patients are negative or low positive. In fact, what is even more comical is that the quantity of antibodies in plasma is probably too little to do anything. And the ultimate irony is that therapy works in isolation, but here we had a plethora of medicines being administered, and it was not possible to pinpoint what was working behind the treatment.

Plasma does not come cheap, as it has to be extracted from patients. Thanks to the CM calling for plasma donation with great zeal and fanfare, the concept spread like wildfire. Intermediaries and ‘scamsters’ came in, and patients paid lakhs to get treatment, that too with dubious efficacy. Most doctors were inundated with calls for plasma, and we didn’t know what and where to arrange it for so many patients.

I know of patients who sold their belongings and went broke, partly because of plasma therapy and of course, Remdesivir, which has now been yanked off from all the guidelines. One of the members of our department, who had recovered from Covid-19, needed to give plasma to her own grandfather. He was admitted to the hospital, administered plasma but to no avail.

Trading fact for fame

Therefore, it is a must to understand the value of a placebo trial. Here, an identical-looking therapy is given to assess whether the active therapy—plasma, in this case—does anything substantial. A 30 per cent response rate is considered to be mostly placebo, or inactive, and that is the value of a placebo-controlled study.

There are numerous variables that determine the success of therapy in Covid-19, and assigning the credit to plasma showed a remarkable lack of foresight. At this juncture, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), in a multicentric study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ), found that plasma wasn’t so good. But the public opinion swayed by the hospitals who pioneered the concept pilloried the paper and trashed it. Such was the distrust in our own country’s research that none wanted to get off the plasma bandwagon. Countless patients spent their life savings on what was a highly questionable therapy. And the charade continued till the second wave subsided.

The breakthrough

As always, we waited for a foreign journal to agree to a local finding, which was not surprising to a lot of us in the government hospitals. The landmark paper in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) showed that there was “No significant differences in clinical status or overall mortality between patients treated with convalescent plasma and those who received placebo.” It has been cited 455 times since it was published in February 2021. The number exceeds the citations of any of the papers published by the ‘experts’ who rolled out an untried therapy on the nation.

To add insult to injury, a section of the print media, which studiously avoided criticising them because their publications were the benefactors of full pages advertisements on plasma banks. To make it worse, some of the names suggested for the Padma awards this year included the plasma therapy pioneers.

Who takes the responsibility?

In retrospect, what needs to be asked is—who will pay for the loss of life savings and the death of patients who were given plasma therapy? Who will fill in the gaps for the distrust in medical care? Will the experts apologise? Who will apologise for pillorying the ICMR’s report that could have nipped this in the bud? But no one really apologises for such things in India.

As Donald Keough said, “The truth is, we are not that dumb and we are not that smart.” The plasma blitzkrieg was neither dumb nor smart; it was callous, and someone should be paying for the negligence today or tomorrow.

Plasma therapy was administered to Covid-19 patients during the second wave in India | Wikipedia

Plasma therapy was administered to Covid-19 patients during the second wave in India | WikipediaThe closing pages of the 18th-century masterpiece fiction The Story of the Stone revealed the essence of the Tao’s message. In Lao Tzu’s words, it means that “Things are not as they seem, that the Eloquent may Stammer, that Perfection may seem Flawed, that Truth is Fiction, Fiction Truth.”

The truth is neither black nor white, it’s grey—the handling of the second wave of Covid-19 is a testimony to that fact.

Disaster that escaped public eye

In the midst of the second wave of Covid-19 with panic all around, a lot of therapeutic disasters were played out, and without a doubt, they were inspired by a lack of knowledge. Instead, they were fueled with a desire for one-upmanship and copycat fame. Some of the doctors unwittingly orchestrated this therapeutic mess. On one side, we had the armchair experts who were not running Covid-19 centres and had shut down their institutes. On the other, doctors in central government hospitals like the Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in Delhi were running Out Patient Departments (OPDs) and wards. They were possibly following half-baked regimens with little proof, as there were lives at stake.

While some medications were possibly harmless and cheap like Ivermectin or HCQS, the others were ridiculously expensive, and no one was wiser about their efficacy. One of them was plasma therapy. Of course, the Indian medical system and healthcare did not have the time for a randomised trial to test a placebo. But the origin of the mess was thus created right here in the capital of the country.

One may ask—who would be the expert to decide on its efficacy? The clear answer is a clinician in a hospital, handling patients with an active plasma extraction centre. But what transpired is that a centre dedicated to liver care with nil experience in Covid-19 treatment proposed the idea that plasma might help. Then came the now-famous statement of Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, saying that Delhi opened the first plasma bank in the world. That set off a chain reaction, and within a few weeks, hospitals followed suit.

It wasn’t the solution

Plasma is a component of the blood that is believed to have antibodies to diseases. Here, it was believed that Covid-19 patients would benefit from such therapy. This was when even the use of Intravenous immunoglobulin (IV IgG), a related plasma-based therapy that had been available for years, wasn’t effective in most disorders. This was also when we all knew that the so-called antibody tests of Covid-19 patients are negative or low positive. In fact, what is even more comical is that the quantity of antibodies in plasma is probably too little to do anything. And the ultimate irony is that therapy works in isolation, but here we had a plethora of medicines being administered, and it was not possible to pinpoint what was working behind the treatment.

Plasma does not come cheap, as it has to be extracted from patients. Thanks to the CM calling for plasma donation with great zeal and fanfare, the concept spread like wildfire. Intermediaries and ‘scamsters’ came in, and patients paid lakhs to get treatment, that too with dubious efficacy. Most doctors were inundated with calls for plasma, and we didn’t know what and where to arrange it for so many patients.

I know of patients who sold their belongings and went broke, partly because of plasma therapy and of course, Remdesivir, which has now been yanked off from all the guidelines. One of the members of our department, who had recovered from Covid-19, needed to give plasma to her own grandfather. He was admitted to the hospital, administered plasma but to no avail.

Trading fact for fame

Therefore, it is a must to understand the value of a placebo trial. Here, an identical-looking therapy is given to assess whether the active therapy—plasma, in this case—does anything substantial. A 30 per cent response rate is considered to be mostly placebo, or inactive, and that is the value of a placebo-controlled study.

There are numerous variables that determine the success of therapy in Covid-19, and assigning the credit to plasma showed a remarkable lack of foresight. At this juncture, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), in a multicentric study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ), found that plasma wasn’t so good. But the public opinion swayed by the hospitals who pioneered the concept pilloried the paper and trashed it. Such was the distrust in our own country’s research that none wanted to get off the plasma bandwagon. Countless patients spent their life savings on what was a highly questionable therapy. And the charade continued till the second wave subsided.

The breakthrough

As always, we waited for a foreign journal to agree to a local finding, which was not surprising to a lot of us in the government hospitals. The landmark paper in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) showed that there was “No significant differences in clinical status or overall mortality between patients treated with convalescent plasma and those who received placebo.” It has been cited 455 times since it was published in February 2021. The number exceeds the citations of any of the papers published by the ‘experts’ who rolled out an untried therapy on the nation.

To add insult to injury, a section of the print media, which studiously avoided criticising them because their publications were the benefactors of full pages advertisements on plasma banks. To make it worse, some of the names suggested for the Padma awards this year included the plasma therapy pioneers.

Who takes the responsibility?

In retrospect, what needs to be asked is—who will pay for the loss of life savings and the death of patients who were given plasma therapy? Who will fill in the gaps for the distrust in medical care? Will the experts apologise? Who will apologise for pillorying the ICMR’s report that could have nipped this in the bud? But no one really apologises for such things in India.

As Donald Keough said, “The truth is, we are not that dumb and we are not that smart.” The plasma blitzkrieg was neither dumb nor smart; it was callous, and someone should be paying for the negligence today or tomorrow.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)