John O'Sullivan in The Economist

THERE IS NOTHING dark, still less satanic, about the Revolution Mill in Greensboro, North Carolina. The tall yellow-brick chimney stack, with red bricks spelling “Revolution” down its length, was built a few years after the mill was established in 1900. It was a booming time for local enterprise. America’s cotton industry was moving south from New England to take advantage of lower wages. The number of mills in the South more than doubled between 1890 and 1900, to 542. By 1938 Revolution Mill was the world’s largest factory exclusively making flannel, producing 50m yards of cloth a year.

The main mill building still has the springy hardwood floors and original wooden joists installed in its heyday, but no clacking of looms has been heard here for over three decades. The mill ceased production in 1982, an early warning of another revolution on a global scale. The textile industry was starting a fresh migration in search of cheaper labour, this time in Latin America and Asia. Revolution Mill is a monument to an industry that lost out to globalisation.

In nearby Thomasville, there is another landmark to past industrial glory: a 30-foot (9-metre) replica of an upholstered chair. The Big Chair was erected in 1950 to mark the town’s prowess in furniture-making, in which North Carolina was once America’s leading state. But the success did not last. “In the 2000s half of Thomasville went to China,” says T.J. Stout, boss of Carsons Hospitality, a local furniture-maker. Local makers of cabinets, dressers and the like lost sales to Asia, where labour-intensive production was cheaper.

The state is now finding new ways to do well. An hour’s drive east from Greensboro is Durham, a city that is bursting with new firms. One is Bright View Technologies, with a modern headquarters on the city’s outskirts, which makes film and reflectors to vary the pattern and diffusion of LED lights. The Liggett and Myers building in the city centre was once the home of the Chesterfield cigarette. The handsome building is now filling up with newer businesses, says Ted Conner of the Durham Chamber of Commerce. Duke University, the centre of much of the city’s innovation, is taking some of the space for labs.

North Carolina exemplifies both the promise and the casualties of today’s open economy. Yet even thriving local businesses there grumble that America gets the raw end of trade deals, and that foreign rivals benefit from unfair subsidies and lax regulation. In places that have found it harder to adapt to changing times, the rumblings tend to be louder. Across the Western world there is growing unease about globalisation and the lopsided, unstable sort of capitalism it is believed to have wrought.

A backlash against freer trade is reshaping politics. Donald Trump has clinched an unlikely nomination as the Republican Party’s candidate in November’s presidential elections with the support of blue-collar men in America’s South and its rustbelt. These are places that lost lots of manufacturing jobs in the decade after 2001, when America was hit by a surge of imports from China (which Mr Trump says he will keep out with punitive tariffs). Free trade now causes so much hostility that Hillary Clinton, the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate, was forced to disown the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade deal with Asia that she herself helped to negotiate. Talks on a new trade deal with the European Union, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), have stalled. Senior politicians in Germany and France have turned against it in response to popular opposition to the pact, which is meant to lower investment and regulatory barriers between Europe and America.

Keep-out signs

The commitment to free movement of people within the EU has also come under strain. In June Britain, one of Europe’s stronger economies, voted in a referendum to leave the EU after 43 years as a member. Support for Brexit was strong in the north of England and Wales, where much of Britain’s manufacturing used to be; but it was firmest in places that had seen big increases in migrant populations in recent years. Since Britain’s vote to leave, anti-establishment parties in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and Austria have called for referendums on EU membership in their countries too. Such parties favour closed borders, caps on migration and barriers to trade. They are gaining in popularity and now hold sway in governments in eight EU countries. Mr Trump, for his part, has promised to build a wall along the border with Mexico to keep out immigrants.

There is growing disquiet, too, about the unfettered movement of capital. More of the value created by companies is intangible, and businesses that rely on selling ideas find it easier to set up shop where taxes are low. America has clamped down on so-called tax inversions, in which a big company moves to a low-tax country after agreeing to be bought by a smaller firm based there. Europeans grumble that American firms engage in too many clever tricks to avoid tax. In August the European Commission told Ireland to recoup up to €13 billion ($14.5 billion) in unpaid taxes from Apple, ruling that the company’s low tax bill was a source of unfair competition.

Free movement of debt capital has meant that trouble in one part of the world (say, America’s subprime crisis) quickly spreads to other parts. The fickleness of capital flows is one reason why the EU’s most ambitious cross-border initiative, the euro, which has joined 19 of its 28 members in a currency union, is in trouble. In the euro’s early years, countries such as Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain enjoyed ample credit and low borrowing costs, thanks to floods of private short-term capital from other EU countries. When crisis struck, that credit dried up and had to be replaced with massive official loans, from the ECB and from bail-out funds. The conditions attached to such support have caused relations between creditor countries such as Germany and debtors such as Greece to sour.

Some claim that the growing discontent in the rich world is not really about economics. After all, Britain and America, at least, have enjoyed reasonable GDP growth recently, and unemployment in both countries has dropped to around 5%. Instead, the argument goes, the revolt against economic openness reflects deeper anxieties about lost relative status. Some arise from the emergence of China as a global power; others are rooted within individual societies. For example, in parts of Europe opposition to migrants was prompted by the Syrian refugee crisis. It stems less from worries about the effect of immigration on wages or jobs than from a perceived threat to social cohesion.

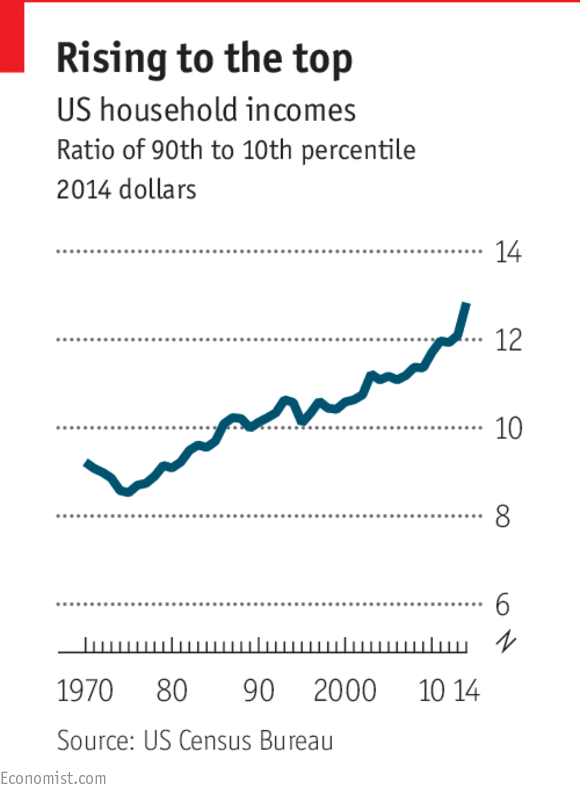

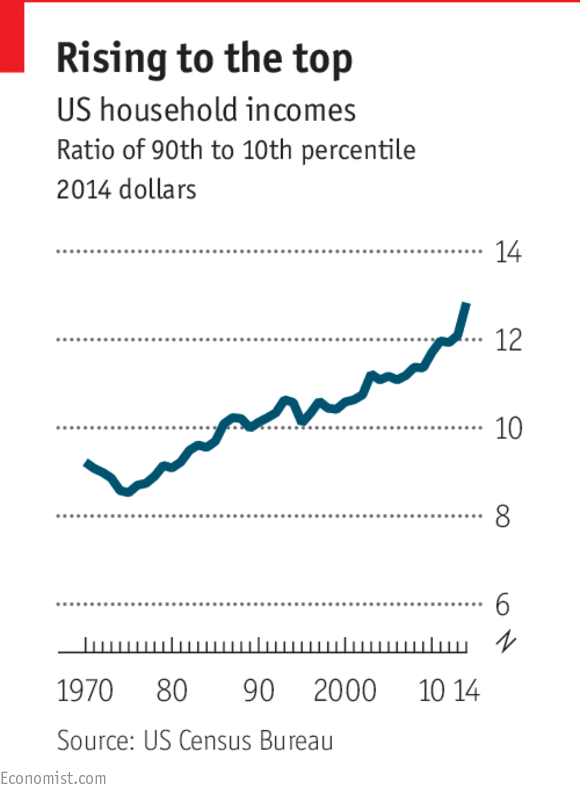

But there is a material basis for discontent nevertheless, because a sluggish economic recovery has bypassed large groups of people. In America one in six working-age men without a college degree is not part of the workforce, according to an analysis by the Council of Economic Advisers, a White House think-tank. In Britain, though more people than ever are in work, wage rises have not kept up with inflation. Only in London and its hinterland in the south-east has real income per person risen above its level before the 2007-08 financial crisis. Most other rich countries are in the same boat. A report by the McKinsey Global Institute, a think-tank, found that the real incomes of two-thirds of households in 25 advanced economies were flat or fell between 2005 and 2014, compared with 2% in the previous decade. The few gains in a sluggish economy have gone to a salaried gentry.

This has fed a widespread sense that an open economy is good for a small elite but does nothing for the broad mass of people. Even academics and policymakers who used to welcome openness unreservedly are having second thoughts. They had always understood that free trade creates losers as well as winners, but thought that the disruption was transitory and the gains were big enough to compensate those who lose out. However, a body of new research suggests that China’s integration into global trade caused more lasting damage than expected to some rich-world workers. Those displaced by a surge in imports from China were concentrated in pockets of distress where alternative jobs were hard to come by.

It is not easy to establish a direct link between openness and wage inequality, but recent studies suggest that trade plays a bigger role than previously thought. Large-scale migration is increasingly understood to conflict with the welfare policy needed to shield workers from the disruptions of trade and technology.

The consensus in favour of unfettered capital mobility began to weaken after the East Asian crises of 1997-98. As the scale of capital flows grew, the doubts increased. A recent article by economists at the IMF entitled “Neoliberalism: Oversold?” argued that in certain cases the costs to economies of opening up to capital flows exceed the benefits.

Multiple hits

This special report will ask how far globalisation, defined as the freer flow of trade, people and capital around the world, is responsible for the world’s economic ills and whether it is still, on balance, a good thing. A true reckoning is trickier than it might appear, and not just because the main elements of economic openness have different repercussions. Several other big upheavals have hit the world economy in recent decades, and the effects are hard to disentangle.

First, jobs and pay have been greatly affected by technological change. Much of the increase in wage inequality in rich countries stems from new technologies that make college-educated workers more valuable. At the same time companies’ profitability has increasingly diverged. Online platforms such as Amazon, Google and Uber that act as matchmakers between consumers and producers or advertisers rely on network effects: the more users they have, the more useful they become. The firms that come to dominate such markets make spectacular returns compared with the also-rans. That has sometimes produced windfalls at the very top of the income distribution. At the same time the rapid decline in the cost of automation has left the low- and mid-skilled at risk of losing their jobs. All these changes have been amplified by globalisation, but would have been highly disruptive in any event.

The second source of turmoil was the financial crisis and the long, slow recovery that typically follows banking blow-ups. The credit boom before the crisis had helped to mask the problem of income inequality by boosting the price of homes and increasing the spending power of the low-paid. The subsequent bust destroyed both jobs and wealth, but the college-educated bounced back more quickly than others. The free flow of debt capital played a role in the build-up to the crisis, but much of the blame for it lies with lax bank regulation. Banking busts happened long before globalisation.

Superimposed on all this was a unique event: the rapid emergence of China as an economic power. Export-led growth has transformed China from a poor to a middle-income country, taking hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. This achievement is probably unrepeatable. As the price of capital goods continues to fall sharply, places with large pools of cheap labour, such as India or Africa, will find it harder to break into global supply chains, as China did so speedily and successfully.

This special report will disentangle these myriad influences to assess the impact of the free movement of goods, capital and people. It will conclude that some of the concerns about economic openness are valid. The strains inflicted by a more integrated global economy were underestimated, and too little effort went into helping those who lost out. But much of the criticism of openness is misguided, underplaying its benefits and blaming it for problems that have other causes. Rolling it back would leave everyone worse off.

Editorial in The Dawn

Nearly one and a half billion people in two countries — India and Pakistan — appear to be held hostage to conspiracy, rumour and reckless warmongering. That needs to stop, and it needs to stop immediately.

On Thursday, 11 days after the Uri attack and seemingly an eternity in Pak-India sabre-rattling and diplomatic tensions, another layer of confusion and chaos was added to one of the world’s most complicated bilateral relationships.

With the facts of the Uri attack yet to be established or shared with the world, a new, potentially larger, set of questions has now overshadowed an already fraught situation.

What happened along the Line of Control between midnight and early morning on Thursday is a story that Indian authorities appear to be very clear about and the Indian media has reported with relish. But virtually nothing has been independently confirmed about the events along the LoC, an area that is effectively cordoned off from the media in both countries and where the local population is unlikely to know the facts or be willing to speak candidly.

What is clear is that something did happen at several points along the LoC in the early hours of Thursday morning. At the very least, Pakistani and Indian forces exchanged fire in which two Pakistani soldiers died.

That is a sad, if long-standing, reality of the region: whenever tensions between the two countries are high, parts of the LoC see live ammunition fired, the lives of local populations disrupted and several casualties among security personnel and civilians.

Indeed, two summers ago, with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi newly installed in office, the LoC saw a series of skirmishes that progressively escalated until reaching crisis point around mid-October. That set of events was supposedly meant to herald the start of a new, so-called get-tough policy by India.

Eventually, better sense prevailed and by September 2015 the DG Rangers and DG Border Security Force met and agreed to renew the LoC ceasefire. The Pathankot attack earlier this year, which involved infiltration across the Working Boundary, did not materially change the situation along the LoC, but unrest in India-held Kashmir and the Uri attack appear to have done so.

At this point, it is imperative to establish the facts quickly. The wild cheering that greeted the government’s accounts of events in India may become a dangerous precedent and create a new set of expectations in a region where war in an overtly nuclear environment would be catastrophic for both countries.

Facts, however, would help nudge the situation towards de-escalation, given signalling from the Pakistani state and Indian government.

Pakistani policymakers, both civilian and military, have reacted sensibly, and appear to be resisting Indian attempts to bait Pakistan. But the media echo chamber — jingoistic, fiercely nationalistic and often removed from reality — can have unpredictable effects, especially when it comes to whipping up warlike sentiment among the populations of the two countries.

Quickly establishing two sets of facts, of events along the LoC on Thursday and the Uri attack, would switch a media narrative from punch and counter-punch and allow the two states to work on how to ratchet down tensions along the LoC.

The Modi government, despite its hawkish instincts and muscle-flexing, has indicated an awareness of the dangers of unrestrained rhetoric. Facts will help clear the miasma and introduce the necessary rationality into a debate that is increasingly unhinged.

Clearly, the problems in the region are not unilateral and one-directional. Pakistan has pursued flawed policies in the past and could do more to help end the menace of terrorism in the region. But this is not an area of straightforward cause and effect, nor are the broader issues of the Pak-India relationship of immediate relevance.

First and foremost, the priority of the leaderships of Pakistan and India should be to ensure that no matter what the circumstances and no matter what the concerns, the path to war is not taken.

India suffered a blow in Uri as it did in Pathankot. It has a right to expect justice and Pakistan has a responsibility to investigate any links to citizens of this country. But what has been unleashed in India since the seemingly exaggerated claims of so-called surgical strikes along the LoC is frightening and wildly destabilising.

If now is not a propitious time for a dialogue of peace, it is the time for some serious introspection.

Only a few days ago, the Indian prime minister talked of a joint war against poverty; he must now also resist the poverty of ideas and the temptation to take the low, dangerous road.

by Oliver Burkeman in The Guardian

Should you choose time over money, or money over time? This is one of those so-called dilemmas of happiness that isn’t really a dilemma at all, because the answer’s so painfully obvious. Circumstances might oblige you to choose money over time. But if you truly, ultimately value a large bank balance over meaningful experiences, you’re what’s known in the psychological literature as a doofus. Money, after all, is just an instrument for obtaining other things, including time – whereas time is all we’ve got. And to make matters worse, you can’t save it up: if money worked like time, every new deposit into your account would be immediately eliminated by a transaction fee of exactly the same size. However much you hate your bank, it’s surely not that bad.

And yet we do choose money over time, again and again, even when basic material wellbeing doesn’t demand it. Partly, no doubt, that’s because even well-off people fear future poverty. But it’s also because the time/money trade-off rarely presents itself in simple ways. Suppose you’re offered a better-paid job that requires a longer commute (more money in return for less time); but then again, that extra cash could lead to more or better time in future, in the form of nicer holidays, or a more secure retirement. Which choice prioritises time, and which money? It’s hard to say.

Thankfully, a new study sheds a little light on the matter. The researchers Hal Hershfield, Cassie Mogilner and Uri Barnea surveyed more than 4,000 Americans to determine whether they valued time or money more, and how happy they were. A clear majority, 64%, preferred money – but those who valued time were happier. Nor was it only those rich enough to not stress about money who preferred time: after they controlled for income, the effect remained. Older people, married people and parents were more likely to value time, which makes sense: older people have less time left, while those with spouses and kids presumably either cherish time with them, or feel they steal all their time. Or both.

The crucial finding here is that it’s not having more time that makes you happier, but valuing it more. Economists continue to argue about whether money buys happiness – but few doubt that being comfortably off is more pleasant than struggling to make ends meet. This study makes a different point: it implies that even if you’re scraping by, and thus forced to focus on money, you’ll be happier if deep down you know it’s time that’s most important.

It also contains ironic good news for those of us who feel basically secure, moneywise, but horribly pushed for time. If you strongly wish you had more time, as I do, who could accuse you of not valuing it? At least my craving for more time shows that my priorities are in order, and maybe that means I’ll savour any spare time I do get. We talk about scarce time like it’s a bad thing. But scarcity’s what makes us treat things as precious, too.

Youssef El Gingihy in The Independent

Jeremy Corbyn's conference speech yesterday underlined exactly why he has been subjected to a ferocious smear campaign. We have heard an endless catalogue of critiques: That Corbyn lacks leadership; that he is not electable; that Labour has become a protest party infiltrated by the far left. Yet the real reason behind these attacks is that Corbyn is a clear and present danger to powerful, vested interests.

For the first time in a generation, a Labour leader is truly challenging the cosy political consensus extending through the Thatcher-Blair-Cameron axis. The policies taking shape represent a clean break from several decades of deregulated free market economics.

Corbyn has positioned Labour as an anti-austerity party. He emphasised that the financial sector caused the 2008 crisis not public spending. This is important as Miliband and Balls mystifyingly failed to make this argument. One can only surmise that they were eager not to offend the City of London.

Corbyn promised to reverse privatisation of public services. This would mean renationalisation of the railways. It would mean restoring a public NHS reversing its privatisation and conversion into a private health insurance system.

It would mean an end to the outsourcing of council services. It would mean returning public services into public hands. And none of this is radical. Polling shows the majority of the public, including Conservative voters, is in favour.

It is no surprise that Richard Branson and Virgin seemingly used Traingate in an attempt to discredit Corbyn. Virgin would stand to lose billions in contracts if such policies went ahead. As would many other corporate interests - the likes of Serco, G4S, Capita and Unitedhealth to name a few.

Corbyn promised Labour will build enough social housing and regulate the housing market. Again, property developers, investors and construction firms would stand to lose from the restoration of housing as a social good rather than a financial instrument.

Corbyn vowed that bankers and financial speculators cannot be allowed to wreak havoc again. Regulation of the financial sector will have the City running scared - the party may well be truly over for them. Deregulated finance has resulted in industrial scale corruption profiting a tiny elite at the expense of ordinary people. This was evident not only during the crash but in the raft of scandals since, including LIBOR and PPI.

Corbyn added that the wealthy must pay their fair share of taxes. Labour would take effective steps to end tax avoidance and evasion. This would need to start with winding down the offshore empire much of which comes under the influence of the UK and the City of London.

Corbyn highlighted the grotesque inequalities driven by neoliberalism. The result has seen millions of ordinary people abandoned by a system that does not work for them. Here, Corbyn again broke with the consensus pointing out that immigration is not to blame. Scapegoating of migrants is convenient for elites keen to distract from the damage that they are causing. Corbyn emphasised that it is exploitative corporations, which are to blame for low wages not migrants. Over-stretched public services are down to Conservative cuts not immigration. However, after years of xenophobic anti-migrant rhetoric, winning this argument will require plenty of hard work.

On the economy, Corbyn promised investment with £500bn of public spending and a national investment bank. He also promised investment in research and development, education and skilling up of the workforce.

Yet none of this is especially controversial. Much of it is increasingly accepted as common sense amongst economists.

It is Corbyn's reset on foreign policy, which is truly intolerable for the establishment.

Corbyn spoke of a peaceful and just foreign policy. There would be no more imperial wars destroying the lives of millions; generating terrorism and migration crises. Arms sales to countries committing war crimes would be banned starting with Saudi Arabia. This will have set alarm bells ringing amongst the nexus of intelligence agencies, defence contractors and corporates. Corbyn is directly challenging the Atlanticist relationship paramount to the US-UK establishment and its global hegemony, particularly in the Middle East.

It is no surprise that the Conservatives and their mainstream media cheerleaders have therefore attacked Corbyn. The most damaging attacks, though, have come from his parliamentary party. The process of disentangling from the New Labour machine captured by corporate interests may still generate more damage.

As Corbyn and McDonnell have both made abundantly clear, socialism is no longer a dirty word. Corbyn's Labour - the largest party in Western Europe - is powering forward with a vision of forward-looking 21st century socialism.