Ranjana Srivastava in The Guardian

Our consultation is nearly finished when my patient leans forward, and says, “So, doctor, in all this time, no one has explained this. Exactly how will I die?” He is in his 80s, with a head of snowy hair and a face lined with experience. He has declined a second round of chemotherapy and elected to have palliative care. Still, an academic at heart, he is curious about the human body and likes good explanations.

“What have you heard?” I ask. “Oh, the usual scary stories,” he responds lightly; but the anxiety on his face is unmistakable and I feel suddenly protective of him.

“Would you like to discuss this today?” I ask gently, wondering if he might want his wife there.

“As you can see I’m dying to know,” he says, pleased at his own joke.

If you are a cancer patient, or care for someone with the illness, this is something you might have thought about. “How do people die from cancer?” is one of the most common questions asked of Google. Yet, it’s surprisingly rare for patients to ask it of their oncologist. As someone who has lost many patients and taken part in numerous conversations about death and dying, I will do my best to explain this, but first a little context might help.

Some people are clearly afraid of what might be revealed if they ask the question. Others want to know but are dissuaded by their loved ones. “When you mention dying, you stop fighting,” one woman admonished her husband. The case of a young patient is seared in my mind. Days before her death, she pleaded with me to tell the truth because she was slowly becoming confused and her religious family had kept her in the dark. “I’m afraid you’re dying,” I began, as I held her hand. But just then, her husband marched in and having heard the exchange, was furious that I’d extinguish her hope at a critical time. As she apologised with her eyes, he shouted at me and sent me out of the room, then forcibly took her home.

It’s no wonder that there is reluctance on the part of patients and doctors to discuss prognosis but there is evidence that truthful, sensitive communication and where needed, a discussion about mortality, enables patients to take charge of their healthcare decisions, plan their affairs and steer away from unnecessarily aggressive therapies. Contrary to popular fears, patients attest that awareness of dying does not lead to greater sadness, anxiety or depression. It also does not hasten death. There is evidence that in the aftermath of death, bereaved family members report less anxiety and depression if they were included in conversations about dying. By and large, honesty does seem the best policy.

Studies worryingly show that a majority of patients are unaware of a terminal prognosis, either because they have not been told or because they have misunderstood the information. Somewhat disappointingly, oncologists who communicate honestly about a poor prognosis may be less well liked by their patient. But when we gloss over prognosis, it’s understandably even more difficult to tread close to the issue of just how one might die.

Thanks to advances in medicine, many cancer patients don’t die and the figures keep improving. Two thirds of patients diagnosed with cancer in the rich world today will survive five years and those who reach the five-year mark will improve their odds for the next five, and so on. But cancer is really many different diseases that behave in very different ways. Some cancers, such as colon cancer, when detected early, are curable. Early breast cancer is highly curable but can recur decades later. Metastatic prostate cancer, kidney cancer and melanoma, which until recently had dismal treatment options, are now being tackled with increasingly promising therapies that are yielding unprecedented survival times.

But the sobering truth is that advanced cancer is incurable and although modern treatments can control symptoms and prolong survival, they cannot prolong life indefinitely. This is why I think it’s important for anyone who wants to know, how cancer patients actually die.

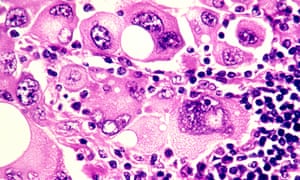

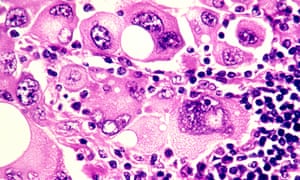

‘Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food’ Photograph: Phanie / Alamy/Alamy

“Failure to thrive” is a broad term for a number of developments in end-stage cancer that basically lead to someone slowing down in a stepwise deterioration until death. Cancer is caused by an uninhibited growth of previously normal cells that expertly evade the body’s usual defences to spread, or metastasise, to other parts. When cancer affects a vital organ, its function is impaired and the impairment can result in death. The liver and kidneys eliminate toxins and maintain normal physiology – they’re normally organs of great reserve so when they fail, death is imminent.

Cancer cells release a plethora of chemicals that inhibit appetite and affect the digestion and absorption of food, leading to progressive weight loss and hence, profound weakness. Dehydration is not uncommon, due to distaste for fluids or an inability to swallow. The lack of nutrition, hydration and activity causes rapid loss of muscle mass and weakness. Metastases to the lung are common and can cause distressing shortness of breath – it’s important to understand that the lungs (or other organs) don’t stop working altogether, but performing under great stress exhausts them. It’s like constantly pushing uphill against a heavy weight.

Cancer patients can also die from uncontrolled infection that overwhelms the body’s usual resources. Having cancer impairs immunity and recent chemotherapy compounds the problem by suppressing the bone marrow. The bone marrow can be considered the factory where blood cells are produced – its function may be impaired by chemotherapy or infiltration by cancer cells.Death can occur due to a severe infection. Pre-existing liver impairment or kidney failure due to dehydration can make antibiotic choice difficult, too.

You may notice that patients with cancer involving their brain look particularly unwell. Most cancers in the brain come from elsewhere, such as the breast, lung and kidney. Brain metastases exert their influence in a few ways – by causing seizures, paralysis, bleeding or behavioural disturbance. Patients affected by brain metastases can become fatigued and uninterested and rapidly grow frail. Swelling in the brain can lead to progressive loss of consciousness and death.

In some cancers, such as that of the prostate, breast and lung, bone metastases or biochemical changes can give rise to dangerously high levels of calcium, which causes reduced consciousness and renal failure, leading to death.

Uncontrolled bleeding, cardiac arrest or respiratory failure due to a large blood clot happen – but contrary to popular belief, sudden and catastrophic death in cancer is rare. And of course, even patients with advanced cancer can succumb to a heart attack or stroke, common non-cancer causes of mortality in the general community.

You may have heard of the so-called “double effect” of giving strong medications such as morphine for cancer pain, fearing that the escalation of the drug levels hastens death. But experts say that opioids are vital to relieving suffering and that they typically don’t shorten an already limited life.

It’s important to appreciate that death can happen in a few ways, so I wanted to touch on the important topic of what healthcare professionals can do to ease the process of dying.

In places where good palliative care is embedded, its value cannot be overestimated. Palliative care teams provide expert assistance with the management of physical symptoms and psychological distress. They can address thorny questions, counsel anxious family members, and help patients record a legacy, in written or digital form. They normalise grief and help bring perspective at a challenging time.

People who are new to palliative care are commonly apprehensive that they will miss out on effective cancer management but there is very good evidence that palliative care improves psychological wellbeing, quality of life, and in some cases, life expectancy. Palliative care is a relative newcomer to medicine, so you may find yourself living in an area where a formal service doesn’t exist, but there may be local doctors and allied health workers trained in aspects of providing it, so do be sure to ask around.

Finally, a word about how to ask your oncologist about prognosis and in turn, how you will die. What you should know is that in many places, training in this delicate area of communication is woefully inadequate and your doctor may feel uncomfortable discussing the subject. But this should not prevent any doctor from trying – or at least referring you to someone who can help.

Accurate prognostication is difficult, but you should expect an estimation in terms of weeks, months, or years. When it comes to asking the most difficult questions, don’t expect the oncologist to read between the lines. It’s your life and your death: you are entitled to an honest opinion, ongoing conversation and compassionate care which, by the way, can come from any number of people including nurses, social workers, family doctors, chaplains and, of course, those who are close to you.

Over 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Epicurus observed that the art of living well and the art of dying well were one. More recently, Oliver Sacks reminded us of this tenet as he was dying from metastatic melanoma. If die we must, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the part we can play in ensuring a death that is peaceful.

Polly Toynbee in The Guardian

A fish rots from the head, but the NHS may be rotting from the feet. Podiatry is not up there in the headlines, yet what’s going on in that unglamorous zone is an alarming microcosm of the downward path of the health service. This is a story of the NHS in England in retreat and the private sector filling the vacuum.

You know the big picture from the ever-worsening monthly figures: deteriorating A&E, ambulance and operation waiting times, and a steep rise in bed-blocking. As debts pass £2.5bn, the NHS feels the tightening financial tourniquet.

Now look at it through the prism of just one small corner, as seen from the feet up. Every week 135 people have amputations because diabetes has caused their feet to rot: their circulation goes and then the sensation in their feet, so they don’t notice damage done by rubbing shoes, stubbed toes or stepping on nails. Minor injuries turn into ulcers that if left untreated turn gangrenous, and so the toes, then the foot, then the leg are lost – horrific life-changing damage. Numbers are rising fast, with nearly three million diabetics. The scandal is that 80% of these amputations are preventable – if there were the podiatrists to treat the first signs of foot ulcers. But the numbers employed and in training are falling.

In his surgery, the head of podiatry for Solent NHS Trust, Graham Bowen, is unwrapping the foot of a lifelong diabetic to reveal a large missing chunk of heel, a great red hole nearly through to the bone. This man has already had some toes amputated. He has been having treatment with maggots, bandaged into his wound to eat the dead skin and help healing – and he is slowly improving. Everyone Bowen sees now is at similarly high risk. Small ulcers, incipient ulcers, the ones that need to be caught early (and cheaply) no longer get NHS treatment. “On the NHS we’re essentially firefighting the worst cases now,” says Bowen. “We are going through our lists and discharging all the rest of our patients.”

FacebookTwitterPinterest ‘On a 15-minute visit carers can’t check feet.’ Photograph: Andrew Bret Wallis/Getty Images

But not even all these acute patients get the same optimal treatments, due to the vagaries of the 2012 NHS Act. Solent, a community trust that covers mental health and a host of other services, is used by five different clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), including Southampton, Portsmouth and West Hampshire. Each has its own criteria for what it will pay for, and each is toughening those criteria. Depending on their address, some patients get the very best, others only get what their cash-strapped CCG pays for.

You need to know about diabetic feet to understand the difference in treatments: the conventional and cheapest treatment is a dressing and a removable plastic boot, and telling patients to keep their foot up for months. But patients who can’t feel their feet tend to take off the boot and hobble to make a quick cup of tea. “Ten minutes of putting pressure on the ulcer undoes 23 hours of resting it,” Bowen says, so it takes 52 weeks on average to heal ulcers that way. For £500 extra, a new instant fibreglass cast saves any pressure on ulcers and cures them within eight weeks.

Although the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence says this total-contact cast is the gold standard, most of Bowen’s CCGs won’t pay for it. I watched him putting one on a patient in under half an hour: after nine weekly replacements, that ulcer would be completely healed. For every 10 of the new casts, one amputation is prevented – and each amputation costs the NHS £65,000. Such is the madness of NHS fragmentation, divided between multiple commissioners and providers, all in serious financial trouble, that no one spends a bit more now for others to save later, even when the payback is so quick.

This clinic lost four podiatry posts to save money: though diabetic numbers soar, its budget has been static for five years. “Doing more for less,” he says with the same weary sigh you hear echoing through the NHS. As Bowen goes through the clinic’s books removing all but the most acute cases, he turns away diabetics whose problems should be caught early. He turns away others he used to treat: the old and frail who have become immobile due to foot problems; the partially sighted or people with dementia who have poor home care. On a 15-minute visit carers can’t check feet and find out if they are the reason someone doesn’t get out of bed, toes buckled in, leaving them needlessly incapacitated and heading for residential care sooner than necessary.

What happens to those he takes off his books? “They have to go private, if they can afford it. If not, then nothing.” He used to send them to Age UK, but lack of funds shut that service. Only 5% of podiatry is now done by the NHS so Bowen has set up TipToe, a private practice attached to his NHS clinic. It’s not what he wants, but it keeps prices low and all proceeds go to the NHS.

Alarm bells should ring here: how silently the NHS slides into the private sector. Labour leadership contender Owen Smith has flagged up his team’s research showing private practice has doubled since 2010. Now that many CCGs only pay for one cataract, how many go private for the second eye? As the Guardian’s health policy editor, Denis Campbell, has asked, how many more vital treatments will go this way?

Podiatry is the ground floor of the NHS hierarchy. The profession reckons the NHS in England needs 12,000 practitioners but only has about 3,000 – and that’s falling, despite so many high-risk diabetics needing weekly appointments. Next year podiatry trainees, like nurses, will no longer receive state bursaries, so fewer will apply. They tend to be older, with families, unable to take on a £45,000 debt for a job paying around £35,000 per year. Already student places have been cut by nearly a quarter in five years. Most of the 7,000 amputations a year are preventable. A shocking statistic: half of those who undergo amputations will die within two years.

Only in the details of what’s happening on the frontline can we understand the daily reality of Britain’s shrinking state. Step back and ask how it can be that a country still growing richer can afford less quality care than when it was poorer? Is that the country’s choice? As the NHS slides into the private sector, here is yet another public service in retreat.

Ben Chu in The Independent

“Neither a borrower nor a lender be”, warned Polonius. But should he have added “saver” to that list?

The Bank of England’s latest cut in its base rate has piled even more downward pressure on returns offered by banks on cash balances. Santander this week halved the interest rate on its “123” account, one of the few remaining products on the market that had offered a decent return on savings. And there is talk of another Bank rate cut later this year, perhaps down to just 0.1 per cent. Will it be long before furious savers march on the Bank’s Threadneedle Street headquarters with pitchforks and burning torches in their hands?

They should put the pitchforks down.

------Also read

Ever-lower interest rates have failed. It’s time to raise them

-----

There are a number of serious misconceptions regarding the plight of savers that have gone uncorrected for too long. The first is that “saving” only takes the form of cash held on deposit in current accounts (or slightly longer-term savings accounts) at the bank or building society. The truth is that far more of the nation’s wealth is held in company shares, bonds, pensions and property, than on cash deposit.

Shares and pension pots have been greatly boosted by the Bank’s low interest rates and monetary stimulus since 2009. House prices have also done well, also helped by low rates. Savers complain about low returns on cash, yet fail to appreciate the benefit to the rest of their savings portfolios from monetary stimulus.

There’s no denying that annuity rates (products offered by insurance companies that turn your pension pot into an annual cash flow) are at historic low thanks to rock bottom interest rates. Yet, since last year, savers also have the freedom not to buy an annuity upon retirement thanks to former Chancellor George Osborne’s regulatory liberalisation. People can now keep their savings invested in the stock market, liquidating shares when necessary to fund their outgoings.

There has been talk of the latest cut in Bank base rate pushing up accounting deficits in defined benefit retirement schemes to record levels, clobbering pensioners. But this is another misunderstanding.

Yes, some of these schemes, run by weak employers, could fail and need to be bailed out by the Pension Protection Fund. And this could entail reductions in pension pay outs. Yet the larger negative impact of rising pension deficits is likely to be felt by young people in work, rather than pensioners or imminent retirees.

Firms facing spiralling scheme deficits and regulatory calls to inject in more spare cash to reduce them, might well respond by keeping downward pressure on wages or by reducing hiring. In other words, the bill is likely to be picked up by those workers who are not benefiting, and were never going to benefit, from these (now closed) generous retirement schemes.

Perhaps the biggest misconception about savings is that low returns on cash deposits are somehow all the fault of the Bank of England. This shows a glaring ignorance of the bigger economic picture.

Excess savings in the global economy – in particular from China, Japan, Germany and the Gulf states – have been exerting massive downward on long-term interest rates in western countries for almost two decades. To put it simply, the world has more savings than it is able to digest. It is this global 'savings glut’ that has driven down long-term interest rates, making baseline returns so low everywhere.

It’s legitimate to wonder whether further cuts in short-term rates by the Bank of England will have much positive affect on the UK economy. But the savings lobby seems to believe that it’s the duty of the Bank to raise short-term rates, regardless of the bigger picture, in order to give people a better return on their cash savings today. This would be madness.

Yes, the Bank of England could jack up short-term rates – but the most likely outcome of this would be to deepen the downturn. And for what? It would mean a higher income for cash savers, but survey research suggests most would simply bank the cash gain rather than spending it, delivering no aggregate stimulus to growth.

Share and other asset prices would also most likely take a beating, undermining the rest of savers’ wealth portfolios. Do savers really believe a 10 per cent fall in the value of their house is a price worth paying for a couple of extra percentage points of interest on their current accounts?

Moreover, the Bank of England’s responsibility is to set interest rates for the good of the whole economy, not for one interest group within it. As Andy Haldane, the Bank’s chief economist pointed out at the weekend, keeping rates on hold (never mind increasing them) would considerably increase unemployment. And the people who would suffer in those circumstances would probably be those who have not even had a chance to build up any savings.

No sensible policymaker or economist wants low interest rates for their own sake. They are a means to an end: to help the economy return to its potential growth rate. When growth has hit that target it will, in time, necessitate higher short-term rates to keep inflation in check.

So for short-term rates to rise, the economy needs to pick up speed. That’s what the Bank of England has been trying to achieve since 2009. Yes, the process has been frustratingly protracted, like jumpstarting an old banger with a flat battery, but the situation would have been worse without Threadneedle Street’s efforts.

If savers are frustrated with low deposit returns they should focus their anger on the global savings glut and the failure (and refusal) of governments in Asia and Europe to rebalance their domestic economies. Other legitimate targets are excessive domestic austerity here in Britain, from the coalition and current governments since 2010, which have delivered a feeble recovery since the Great Recession, and also the Brexit vote which has forced the Bank of England into hosing the economy down with yet more emergency monetary support this month.

And if they voted for the latter two – austerity and Brexit – then savers might care to look in the mirror if they want to see one of the true causes of their frustration.

Tim Wigmore in Cricinfo

They are still called the golden team. In 1953, Hungary came to Wembley and eviscerated England 6-3 in the "Match of the Century". A year later, in the 1954 World Cup, Hungary defeated West Germany 8-3 and Brazil 4-2. In a run of 50 games, until the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, they won 42 and lost only one - to West Germany in the 1954 World Cup final.

Yet Euro 2016 was Hungary's first appearance in a major tournament for 30 years. While Hungary's decline is sad, it has been no impediment to football's growth. The most successful sport in the world allows teams to rise and, yes, fall based on merit. So do other sports that are expanding, like basketball, rugby and even baseball.

Cricket, though, takes a very different view. This is the context of the opposition to two divisions: the sport has never been run on merit. The very concept of full membership reflects a sport that has prioritised status above on-field results. That can be seen in how each of the ten Test nations retains permanent votes in the ICC board (while the three votes shared by the 95 Associates and Affiliates are effectively worthless), and how even after recent steps to increase funding for top Associates, Zimbabwe still receive about three times as much ICC revenue as Afghanistan and Ireland.

In all previous World Cups, all Full Members have received automatic qualification as a membership privilege. That will change in 2019, but only while the tournament is contracted to ten teams. And even now cricket refuses to embrace the concept of World Cup qualification being based on a fair and equal process, as has long been the norm in other major sports. Afghanistan and Ireland have a chance to qualify automatically through the ODI rankings table, but this is only a theoretical chance: Afghanistan haven't played a single ODI against a top-nine team since the last World Cup.

The idea of Test status has historically been the most egregious illustration of cricket's contempt for meritocracy. The acquisition and retention of status has always been based on politicking as much as cricket: when Pakistan gained independence, the country had to wait five years to gain full membership. Sri Lanka could have been elevated to Test status years before 1982. And when Bangladesh finally gained Test status in 2000 - their own attempts to win Test status upon independence, 29 years earlier, had failed - they had lost five of the six ODIs they had played against Kenya, whose own application was rejected, in the three years leading up to then. When a member of the Kenyan board later made this point to an ICC official, the response was instructive: "You do not have 100 million people."

So when Sri Lanka Cricket's president Thilanga Sumathipala said, "If someone wants to come up - they can come up, that's no problem", he should really know better. Even the much-vaunted Test Challenge demands that a new team win their first ever series, something no country has ever done, and makes no mention of making the 11th Test side a Full Member too. When opponents of two divisions in Tests speak of how "the smaller countries will lose out" if divisions are introduced, it is clear they are thinking only of Full Members, and not the 95 Associates and Affiliates.

The very administrators charged with maintaining fair play on the pitch - by being vigilant against match-fixing and ball-tampering - often seem determined to avoid it off the field, by preventing emerging countries getting a fair opportunity to rise.

This aversion to merit belittles cricket. It has acted as a roadblock to new teams emerging: Ben Amafrio, executive general manager at Cricket Australia, said recently that cricket has only gained one competitive new team - Sri Lanka - in the last 40 years. In growing the sport, cricket has been dwarfed not merely by football but baseball, basketball and rugby too. This means that many wondrous talents, from Steve Tikolo to Mohammad Shahzad and Hamid Hassan, have rarely had the chance to show the best of themselves. Worse, it has meant that countless other talents have been lost to mainstream international cricket before they have ever had the chance. Names like Muralitharan, Jayasuriya, Aravinda de Silva and Sangakkara would not resonate in the same way had they been unfortunate enough to play in the pre-1982 generation of Sri Lankan cricket, when they could do nothing to gain Test status.

Rejecting meritocracy also damages the standard of cricket - not just because of the talent that does not get to play with the elite but because it allows existing Full Members to get away with an underperforming team without real consequence. This was the point made by New Zealand Cricket chief executive David White recently, when he said that two divisions would "make people look at their high-performance programmes and their systems, so the product of Test cricket will improve as well". It is a lesson that other sports long ago learned.

Meritocracy does not tolerate the stasis and misgovernance that has characterised boards in Sri Lanka, West Indies, Zimbabwe and beyond for far too long. Former Zimbabwe coach Dav Whatmore recently pointed out that ZC are "getting US$ 8-9 million a year and they've got a debt of almost $20m".

Such ICC funding would have gone much further had it been allocated to countries on the basis of merit, not status. And not only have Full Members received far more ICC money, they have also been free of scrutiny in how they spend it. The ICC has long mandated that all Associates and Affiliates submit their financial statements every year, to show where every cent of their ICC funding is going, yet only this year ensured that Full Members do the same.

Where competition has been genuinely embraced, it has led to huge improvements in the quality of the game. That much was recognised by Tim Anderson, the ICC's former head of global development, who said that at Associate and women's level, "the long-standing, merit-based event structures… have all provided building blocks for these improved performances, as has a funding model designed to incentivise and reward performance, not status", in an email to ICC members earlier this year. The contrast with the Full Members' attitude to meritocracy at the top of the men's game did not need to be spelled out.

Like the Hungarian football team and the West Indies cricket team, international teams decline. But while football and other sports allow other rising teams to take their place - and fallen giants to rise again - cricket does not. As sad as the decline of West Indies is, is it any sadder than the best players from Afghanistan, say, being denied the opportunity to play Test cricket because of the misfortune of their nationality?

Across all sports, fans and broadcasters value meritocracy, which gives games context and consequences for victory and defeat. It is this knowledge - and the reality of stagnating TV rights for all bilateral cricket, while those for domestic T20 leagues are soaring - that is now driving the ICC's attempts to introduce two divisions, and a 13-team ODI league. Without embracing the principles of merit, "cricket will lose fans and revenues, threatening its position in the marketplace," warns Simon Chadwick, a sports business expert.

So ingrained is cricket's conservatism that the notion of meritocracy in international cricket is now seen as something radical. In essence, though, it is an insurance policy to safeguard international cricket's future: both its number of competitive teams and its financial viability. Japan's victories over New Zealand and France in the Olympic rugby sevens were the latest reminder of how other sports are aggressively expanding, and in the process weaning themselves off a dangerous over-dependence upon a few countries. Yet cricket essentially retains its traditional colonial footprint, and its economics are still unhealthily reliant upon a coterie of nations - and above all India.

This means that if international cricket becomes even a little less lucrative in Australia, England and India - even if only through the rising appeal of domestic T20 leagues - the entire economy of the international game will suffer. Never mind the cricketing arguments for meritocracy; on a business level, that is poor risk management. The risk to international cricket's future lies not in meritocracy but in rejecting it.