Nadeem F Paracha in The Dawn

Abul Ala Maududi (d.1979), is considered to be one of the most influential Islamic scholars of the 20th century. He is praised for being a highly prolific and insightful intellectual and author who creatively contextualised the political role of Islam in the last century, and consequently gave birth to what became known as ‘Political Islam.’

Simultaneously, his large body of work was also severely critiqued as being contradictory and for being an inspiration to those bent on committing violence in the name of faith.

Interestingly, Maududi’s theories and commentaries received negative criticism not only from those on the left and liberal sides of the divide, but from some of his immediate religious contemporaries as well.

Nevertheless, his thesis on the state, politics and Islam, managed to influence a number of movements within and outside of Pakistan.

For example, the original ideologues of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood organisation (that eventually spread across the Arab world), were directly influenced by Maududi’s writings.

Maududi’s writings also influenced the rise of ‘Islamic’ regimes in Sudan in the 1980s, and more importantly, the same writings were recycled by the Ziaul Haq dictatorship (1977-88), to indoctrinate the initial batches of Afghan insurgents (the ‘mujahideen’), fighting against Soviet troops stationed in Afghanistan.

In the last century, the modern Islamic Utopia that Maududi was conceptualising had become the main motivation behind several political and ideological experiments in various Muslim countries.

However, 21st century politics (in the Muslim world) is not according to the kind enthusiastic reception that Maududi’s ideas received in the second half of the 20th century.

By the early 2000s, almost all experiments based on Maududi’s ideas seemed to have collapsed under their own weight. The imagined Utopia turned into a living dystopia, torn apart by mass level violence (perpetrated in the name of faith) and the gradual retardation of social and economic evolution in a number of Muslim countries, including Pakistan.

This is ironic. Because when compared to the ultimate mindset that his ideas seemed to have ended up planting within various mainstream regimes and clandestine groups, Maududi himself sounds rather broad-minded.

Born in 1903 in Aurangabad, India, Maududi’s intellectual evolution is a fascinating story of a man who, after facing bouts of existential crises, chose to interpret Islam as a political theory to address his own spiritual and ideological impasses.

He did not come raging out of a madressah, swinging a fist at the vulgarities of the modern world. On the contrary, he was born into a family that had relations with the enlightened 19th century Muslim reformist and scholar, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan.

Maududi received his early education at home through private tutors who taught him the Quran, Hadith, Arabic and Persian. At age 12, Maududi was sent to the Oriental High School whose curriculum had been arranged by famous Islamic scholar, Shibli Nomani.

Maududi was studying at a college-level Islamic institution, the Darul Aloom, when he had to rush to Bhopal to look after his ailing father. In Bhopal, he befriended the rebellious Urdu poet and writer, Niaz Fatehpuri.

Fatehpuri’s writings and poetry were highly critical of the orthodox Muslim clergy. This had left him fighting polemical battles with the ulema.

Inspired by Fatehpuri, Maududi too decided to become a writer. In 1919, the then 17-year-old Maududi moved to Delhi, where for the first time he began to study the works of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan in full. This, in turn, led Maududi to study the major works of philosophy, sociology, history and politics authored by leading European thinkers and writers.

In 1929, after resurfacing from his vigorous study of Western philosophical and political thought, Maududi published his first major book, Al-Jihad Fil-Islam. The book is largely a lament on the state of Muslim society in India and in it he attacked the British, modernist Muslims and the orthodox clergy for combining to keep Indian Muslims subdued and weak.

Writing in flowing, rhetorical Urdu, Maududi criticised the Muslim clergy for keeping Muslims away from the study of Western philosophy and science. Maududi suggested that it were these that were at the heart of Western political and economic supremacy and needed to be studied so they could then be effectively dismantled and replaced by an ‘Islamic society’.

In 1941 Maududi formed the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI). The outfit was shaped on the Leninist model of forming a ‘party of a select group of committed and knowledgeable vanguards’ who would attempt to grab state power through revolution.

In an essay that was later republished (in 1980) in a compilation of his writings, Come let us Change This World, Maududi castigated the ulema for ‘being stuck in the past’ and thus halting the emergence of new research and thinking in the field of Islamic scholarship.

He was equally critical of modernist Muslims (including Mohammad Ali Jinnah). In the same essay he lambasted them for understanding Islam through concepts constructed by the West and for believing that religion was a private matter.

Though an opponent of Jinnah and the creation of Pakistan (because he theorised that an ‘Islamic State’ could not be enacted by ‘Westernised Muslims’), Maududi did migrate to the new Muslim-majority country once it came into being in 1947.

In a string of books, mainly Khilafat-o-Malukiyat, Deen-i-Haq, Islamic Law and Constitution and Economic System of Islam, Maududi laid out his precepts of the modern-day ‘Islamic State’.

He was adamant about the need to gain state power to impose his principles of an Islamic State, but cautioned that the society first needed to be Islamised from below (through evangelical action), for such a state to begin imposing Islamic Laws.

In these books he was the first Islamic scholar to use the term ‘Islamic ideology’ (in a political context). The term was later rephrased as ‘Political Islam’ by the western scholarship on the subject.

In 1977 when Maududi agreed to support the Ziaul Haq dictatorship, he was criticised for attempting to grab state power through a Machiavellian military dictator.

Maududi’s decision sparked an intense critique of his ideas by the modernist Islamic scholar, Dr Fazal Rehman Malik. In his book, Islam and Modernity, Dr Malik described Maududi as a populist journalist, rather than a scholar. Malik suggested that Maududi’s writings were ‘shallow’ and crafted only to bag the attention of muddled young men craving for an imagined faith-driven Utopia.

Maududi’s body of work is remarkable in its proficiency and creativity. And indeed, it is also contradictory. He used Western political concepts of the state to explain the modern idea of the Islamic State; and yet he accused modernist Muslims of understanding Islam through Western constructs. He saw no space for monarchies in Islam, yet was entirely uncritical of conservative Arab monarchies. He would often prefix the word Islam in front of various Western economic and political ideas — (Islamic-Economics, Islamic-Banking and Islamic-Constitution) — and yet he reacted aggressively towards the idea of ‘Islamic-Socialism’ that came from his leftist opponents in the 1960s.

Writing in the Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought, Political Anthropologist, Professor Irfan Ahmed, suggested that there was not one Maududi, but many.

He wrote that elements of Leninism, Hegel’s dualism, Jalaluddin Afghani’s Pan-Islamism and various other modern political theories can be found in Maududi’s thesis.

Perhaps this is why Maududi’s ideas managed to appeal to various sections of the urban Muslim middle-classes; modern conservative Muslim movements; and all the way to the more anarchic and reactionary forces.

But the question is, had Maududi been alive today, which one of the many Maududis would he have been most comfortable with in a Muslim world now crammed with raging dystopias?

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 3 January 2016

Thursday, 31 December 2015

UK Floods: What have we done to make the flooding worse?

By Camila Ruz and Jon Kelly in BBC News Magazine

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesFloods have caused havoc across much of the UK. Have decisions made by the public and politicians alike made things worse?

Thousands of homes are without power after Storm Frank as people brace themselves for more flooding.

Dozens of flood warnings remain in place with north-east Scotland at risk of heavy rainfall on Sunday and Monday.

Here are some of the things that it has been suggested have contributed to the problem.

Building on flood plains

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesSome four million residential properties in England currently sit on places with a one in 1,000 risk of flooding each year.

After floods in 2007 that affected 55,000 homes, the government commissioned a review chaired by Sir Michael Pitt to ensure it didn't happen again. The review said it wasn't possible to prevent all building on floodplains but recommended that there should be a strong presumption against it. It also said buildings should avoid creating flood problems for themselves or their neighbours.

But large-scale building on floodplains has continued. In fact, according to the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), housing in areas where flooding is likely has grown at a rate of 1.2% per year since 2011, while the building of residential properties in areas of low risk has risen by just 0.7% over the same period.

Policy-makers are often keen to see brownfield land used for residential development, but these areas are often most vulnerable to flooding. Demand from buyers has fuelled this growth, too.

You might assume that there would be huge drops in property prices after highly publicised floods. But in places like Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, and Cockermouth, Cumbria, which experienced heavy flooding in 2007 and 2009 respectively, prices have remained largely unaffected in the long run.

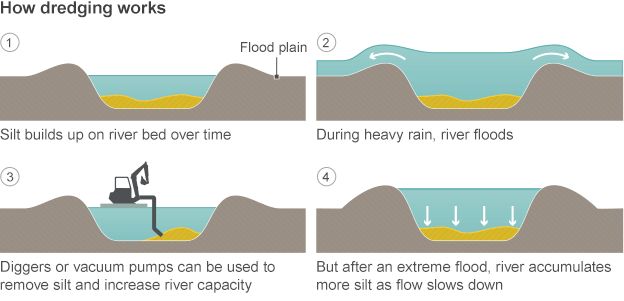

Dredging

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesThe argument over dredging has been going strong since floods in Somerset in 2013-14. At the time, farmers claimed that lack of river dredging had been making the problem worse. "Somerset is suffering from the impacts of two decades of underinvestment with the cessation of dredging along the lowland rivers Parrett and Tone," said the National Farmers Union in their Flooding Manifesto.

Dredging removes the silt that builds up at the bottom of rivers and deepens the channel. Some people say that it helps prevent flooding by making the water flow faster and more efficiently. Supporters of dredging have complained that the European Water Framework Directive prevents it being carried out.

But others have argued that it's not a good idea because the river can still be overwhelmed. When this happens it can cause faster and more dangerous floods downstream. "We've tended to straighten rivers, to canalise them, to embank them and all that rushes the water down to the nearby urban pinch point," explains environmentalist and writer George Monbiot, adding that the flow of water should be slowed down and the rivers lengthened instead.

River straightening

Image copyrightiStock

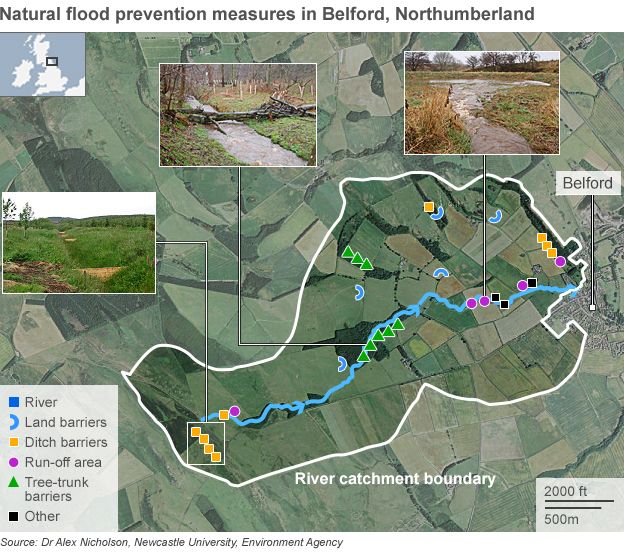

Image copyrightiStockOne way of encouraging a river to take its time in getting to its destination - and therefore reduce the risk of flooding - is to allow it to make large bends called meanders or to braid itself into a network of smaller channels. These twists and turns can help prevent flash floods from racing their way down at full force.

"There still has to be somewhere for that rain to go, you are not going to be able to hold it all back in the hills," explains Monbiot.

Reconnecting a river with its flood plain can also help prevent extreme events downstream. This allows the river to flood in certain areas, storing water in fields until it can be released slowly once the danger has passed. But this has to be controlled.

"If it's not managed carefully, obviously that flooding can have a serious impact on the farming business," says Rob Howells, the NFU's Water Quality Adviser. "The protection of the urban area has to be planned in conjunction with the protection of rural areas to make sure that everything is joined up and to make sure that you are not having unintended consequences elsewhere," he adds.

Destruction of upland habitats

Image copyrightScience Photo Library

Image copyrightScience Photo LibraryTrees can act as a natural flood defence. They have roots that reach deep into the soil, loosening it and allowing water to drain down more easily. A hillside covered in thick vegetation tends to release water more slowly than a bare hill. The compacted soil of farmland can also make the problem worse by reducing the ground's ability to hold water.

This is especially important upstream. Planting woodlands at a stream's upper reaches could help delay the water from reaching the main river. Trees can also end up providing small dams, although this needs to be managed with care.

Beavers would do this work for free, adds Monbiot. "They could be a very useful tool in preventing floods."

The Environment Agency has said that large areas of trees would need to be replanted for them to really make a difference. Flood defences on farmlands upstream might also not have had much effect in preventing the current flooding. "The levels of rainfall in the North West on already saturated ground were unprecedented," says a spokesman from the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). "It is unlikely flood protection on farmland would have made a material difference in such an exceptional flood."

Blanket bogs also play a key role in soaking up rainfall upstream. The peaty soil of a bog can be up to 90% water. Sphagnum mosses growing there can also hold water like a sponge. But many blanket bogs have been drained and their peat cut out which can increase the risk of flooding downstream.

Some people argue that there is not much incentive for farmers to keep land covered in thick vegetation because of EU rules. Land covered with "permanent ineligible features" such as ponds, dense scrub and some woodland can be disqualified from farm subsidies.

Woodland cover has increased in the UK since its lowest point during World War One but the UK is still one of the least wooded countries in Europe. "Planting trees can help to slow the flow of rivers and has an important role to play in reducing flood risk but they need to be located carefully to make sure that they are actually being beneficial," adds Howells.

Flood defences

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesCritics have focused on the effectiveness of existing barriers. Carlisle's £38m flood-defence scheme was breached despite having been constructed only five years before, with an additional half-metre (1ft 8in) added on top to allow for the effects of climate change. There was anger at the decision to lift York's Foss Barrier, a key part of the city's flood defence system, because its pumps were at risk of electrical failure.

During its first year in office, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition announced it was cutting spending on flood defences by 8% compared with previous yearly spend - though the Environment Agency said at the time that the budget had actually been reduced by 27% in cash terms.

Critics have said reductions in maintenance budgets have worsened the problem. Judith Blake, the leader of Leeds City Council said there was a "north-south divide" in efforts to prevent flooding. She said the north of England had not seen "anywhere near the support that we saw going into Somerset", which flooded in 2014, and pointed out that the government had cut funding for a flood defence project in Leeds in 2011. She said there was now a "real anger growing across the North".

However, the prime minister said the government had spent more per head of the population on flood defences in the north than in the south and that £2.3bn would be spent on flood defences by 2020. The government has ordered a major review of flood prevention strategy.

A Defra spokeswoman said £1.7bn of investment into new or expanded flood defences in the previous parliament was an increase on spending from the previous administration. The spokeswoman added that a new six-year spending programme - replacing an annual bidding process for flood defence schemes - has allowed the government to make a long term commitment to protect the £171m spent each year on maintaining defences in real terms.

The concentration of Britons in urban areas - 82% live in towns and cities - has made them especially vulnerable to flooding because concrete surfaces, unlike soil, are almost completely impenetrable to water.

And even when new flood defences are built to protect homes in one area, there are complaints that they often simply cause flooding elsewhere. When the Berkshire town of Wraysbury flooded in 2014, residents said they were being used as "sacrificial lambs" to prevent Maidenhead from being flooded.

Climate change

Cameron has made a link between the floods and climate change. The government anticipates trends which have seen drier summers and wetter winters in the UK to continue. The UK Climate Projections of 2009 estimated a sea-level rise of between 13cm and 76cm for the UK by 2095.

The prime minister has said climate change is one of the biggest challenges the country faces and the government has announced plans for the UK's coal plants to be phased out within 10 years. The Environment Secretary recently announced a National Flood Resilience Review that would look again at flood risk, including the future impact of climate change.

Labour have said climate change should be treated as a national security issue and urged the government to do more. Environmental campaigners have criticisedministers for cutting support for green energy sources.

The climate change summit in Paris agreed a deal to attempt to limit the rise in global temperatures to less than 2C. However, Monbiot says "we have to take urgent action on climate change and go a lot further than the Paris agreement proposed".

The collapse in the price of oil is a challenge to the old world order

Allister Heath in The Telegraph

It is one of life’s mysteries that being wrong about everything has never been much of a barrier to success. Take Thomas Malthus, the British theologian: his big idea was that the number of human beings would necessarily grow faster than the supply of food, leading to calamity. There was little difference, in his mind, between people and rabbits: both were doomed to over-breed, over-consume and starve.

Yet this theory, expounded in 1798 in An Essay on the Principle of Population, one of the most influential books ever written, and now also routinely applied to oil and other resources, is bogus. Unlike rabbits, who are powerless to control their environment, the more we need, the more we eventually find a way of producing: the availability of food and oil are determined by technology and economics, not by some law of nature. Modern techniques (such as fertilisers, genetic selection or fracking) mean that agriculture and the extraction of commodities have become hugely more efficient.

The average British field yielded just over three tons of cereal per hectare per year in 1961; today, it is twice that. Thanks to the spread of free markets and knowledge, the world has never produced so much food, and the number of hungry people worldwide has dropped by 216m since the early Nineties, according to the United Nations.

Ditto oil production: in 2000, the Energy Information Administration estimated that the world contained just over one trillion barrels of untapped oil; since then, proved reserves have shot up by 60pc, increasing every single year despite booming consumption from energy-thirsty emerging markets.

Malthus wasn’t just far too pessimistic about supply: he was also wrong about demand. Rabbits can’t control their birthrates; we can. As more countries embrace markets and globalisation, thus ensuring that their economies develop, global birth rates keep on falling. As to energy consumption, it is just a matter of time before improved battery technology and ever-cheaper solar power finally lessen our dependence on the internal combustion engine and oil. We will eventually be able to feed and fuel the world’s population using significantly less land and fewer hydrocarbons than we do today.

Jesse H Ausubel, an academic at the Rockefeller University in New York, has calculated that an area the size of the Amazonian forest could be returned to wildlife when the average farmer around the world becomes as productive as their US counterparts. Ausubel calls this the Great Reversal: nature’s chance to restore land and sea to their original use. It is an intriguing and exhilarating prospect, made possible by the wonders of capitalism, innovation and human ingenuity.

The abject failure of Malthusianism was, in fact, one of the defining trends of 2015, especially in the oil market; it will continue to be one of the central forces of 2016, impacting everything from how quickly the Bank of England puts up interest rates, to the stability of the Middle East. The price of Brent crude oil, which briefly reached $147 a barrel in 2008, is now down to around $37. Some analysts even believe it could fall briefly to $20, especially if more Iranian supplies than expected hit the global markets.

There are many reasons for this historic collapse. Thanks to shale, America is poised to become a net oil exporter. Opec, the old cartel that wreaked so much havoc in the Seventies, is now all but defunct; its members no longer have the ability to push up oil prices. At the same time, the slowdown in China has reduced demand for energy.

The cost to oil-exporting countries from the lower prices is nearing $2 trillion a year. Drivers, by contrast, have saved a fortune, allowing them to spend the cash on other things and contributing to a strengthening in consumer spending across the Western economies.

Drivers have saved a fortune thanks to low petrol prices

Drivers have saved a fortune thanks to low petrol prices

Manufacturers’ costs have also slumped, facilitating investment and creating jobs. Europe, China and India have been the great winners. In Britain, lower petrol prices have helped eliminate consumer price inflation. Take-home pay has thus shot up after years of austerity. Cheap oil has also delayed – and delayed again – the prospect of a rate hike from the Bank of England, helping borrowers but hurting savers, some of whom had already lost out from their holdings in commodity and oil firms.

Perhaps the biggest impact will be geopolitical. In oil-exporting Venezuela, the public has booted out the Corbynite government whose demented Left-wing policies had led to a shortage of toilet paper. In Russia, the budget deficit is likely to reach alarming levels this year, forcing the country to dip into its reserves and putting pressure on President Putin, especially given his military commitments in Syria.

The Gulf states face the greatest challenge to their viability. Some, such as the UAE, a close ally of the West’s fight against terror, have such large cash reserves that they ought to be able to cope with low oil prices for decades. Others, including Iraq and Bahrain, will find it much tougher; Saudi Arabia has just been forced to pass an emergency budget. All will slash their purchases of Western assets and luxury goods, hitting the London economy.

The West will be hoping that the existing Gulf regimes aren’t replaced by something worse, while also hoping that the collapse in the price of oil will reduce flows of cash to extremist Wahhabi and Salafist groups around the world. If radical Islamist terror groups end up being the biggest losers, the collapse in the oil price could yet end up achieving more than sanctions or Western military intervention ever could; but a successful uprising in somewhere like Saudi could also risk turning a bad situation into a catastrophe.

As for Scotland, the nationalist electorate will eventually have to wake up to the new reality of a world awash with oil. The SNP’s plans for independence didn’t even come close to adding up even when the price of Brent crude was over $100 last year.

At current prices and with output sliding, an independent Scotland that sought to retain the NHS and the welfare state would face immediate bankruptcy.

Forget about politics and slick campaigns: if anything keeps the UK together over the next few years, it will be cheap oil and the latest, abject failure of Malthusianism, one of the most wrong-headed ideologies of the past 200 years.

It is one of life’s mysteries that being wrong about everything has never been much of a barrier to success. Take Thomas Malthus, the British theologian: his big idea was that the number of human beings would necessarily grow faster than the supply of food, leading to calamity. There was little difference, in his mind, between people and rabbits: both were doomed to over-breed, over-consume and starve.

Yet this theory, expounded in 1798 in An Essay on the Principle of Population, one of the most influential books ever written, and now also routinely applied to oil and other resources, is bogus. Unlike rabbits, who are powerless to control their environment, the more we need, the more we eventually find a way of producing: the availability of food and oil are determined by technology and economics, not by some law of nature. Modern techniques (such as fertilisers, genetic selection or fracking) mean that agriculture and the extraction of commodities have become hugely more efficient.

The average British field yielded just over three tons of cereal per hectare per year in 1961; today, it is twice that. Thanks to the spread of free markets and knowledge, the world has never produced so much food, and the number of hungry people worldwide has dropped by 216m since the early Nineties, according to the United Nations.

Ditto oil production: in 2000, the Energy Information Administration estimated that the world contained just over one trillion barrels of untapped oil; since then, proved reserves have shot up by 60pc, increasing every single year despite booming consumption from energy-thirsty emerging markets.

Malthus wasn’t just far too pessimistic about supply: he was also wrong about demand. Rabbits can’t control their birthrates; we can. As more countries embrace markets and globalisation, thus ensuring that their economies develop, global birth rates keep on falling. As to energy consumption, it is just a matter of time before improved battery technology and ever-cheaper solar power finally lessen our dependence on the internal combustion engine and oil. We will eventually be able to feed and fuel the world’s population using significantly less land and fewer hydrocarbons than we do today.

Jesse H Ausubel, an academic at the Rockefeller University in New York, has calculated that an area the size of the Amazonian forest could be returned to wildlife when the average farmer around the world becomes as productive as their US counterparts. Ausubel calls this the Great Reversal: nature’s chance to restore land and sea to their original use. It is an intriguing and exhilarating prospect, made possible by the wonders of capitalism, innovation and human ingenuity.

The abject failure of Malthusianism was, in fact, one of the defining trends of 2015, especially in the oil market; it will continue to be one of the central forces of 2016, impacting everything from how quickly the Bank of England puts up interest rates, to the stability of the Middle East. The price of Brent crude oil, which briefly reached $147 a barrel in 2008, is now down to around $37. Some analysts even believe it could fall briefly to $20, especially if more Iranian supplies than expected hit the global markets.

There are many reasons for this historic collapse. Thanks to shale, America is poised to become a net oil exporter. Opec, the old cartel that wreaked so much havoc in the Seventies, is now all but defunct; its members no longer have the ability to push up oil prices. At the same time, the slowdown in China has reduced demand for energy.

The cost to oil-exporting countries from the lower prices is nearing $2 trillion a year. Drivers, by contrast, have saved a fortune, allowing them to spend the cash on other things and contributing to a strengthening in consumer spending across the Western economies.

Drivers have saved a fortune thanks to low petrol prices

Drivers have saved a fortune thanks to low petrol pricesManufacturers’ costs have also slumped, facilitating investment and creating jobs. Europe, China and India have been the great winners. In Britain, lower petrol prices have helped eliminate consumer price inflation. Take-home pay has thus shot up after years of austerity. Cheap oil has also delayed – and delayed again – the prospect of a rate hike from the Bank of England, helping borrowers but hurting savers, some of whom had already lost out from their holdings in commodity and oil firms.

Perhaps the biggest impact will be geopolitical. In oil-exporting Venezuela, the public has booted out the Corbynite government whose demented Left-wing policies had led to a shortage of toilet paper. In Russia, the budget deficit is likely to reach alarming levels this year, forcing the country to dip into its reserves and putting pressure on President Putin, especially given his military commitments in Syria.

The Gulf states face the greatest challenge to their viability. Some, such as the UAE, a close ally of the West’s fight against terror, have such large cash reserves that they ought to be able to cope with low oil prices for decades. Others, including Iraq and Bahrain, will find it much tougher; Saudi Arabia has just been forced to pass an emergency budget. All will slash their purchases of Western assets and luxury goods, hitting the London economy.

The West will be hoping that the existing Gulf regimes aren’t replaced by something worse, while also hoping that the collapse in the price of oil will reduce flows of cash to extremist Wahhabi and Salafist groups around the world. If radical Islamist terror groups end up being the biggest losers, the collapse in the oil price could yet end up achieving more than sanctions or Western military intervention ever could; but a successful uprising in somewhere like Saudi could also risk turning a bad situation into a catastrophe.

As for Scotland, the nationalist electorate will eventually have to wake up to the new reality of a world awash with oil. The SNP’s plans for independence didn’t even come close to adding up even when the price of Brent crude was over $100 last year.

At current prices and with output sliding, an independent Scotland that sought to retain the NHS and the welfare state would face immediate bankruptcy.

Forget about politics and slick campaigns: if anything keeps the UK together over the next few years, it will be cheap oil and the latest, abject failure of Malthusianism, one of the most wrong-headed ideologies of the past 200 years.

What's the next generation of batsmen learning?

Ian Chappell in Cricinfo

It's now eight years since Misbah-ul-Haq's ill-conceived attempted scoop shot ballooned to short fine leg at the Wanderers Stadium and India were crowned inaugural World T20 champions.

Much has happened in cricket since that exciting five-run victory and the bulk of it revolves around the evolution of T20. Leagues have sprung up like daisies in summer, with the IPL being the most affluent and gaudy, whilst the other two versions of the game - Test and 50-over cricket - have receded into the shadows.

Now that kids from all over the world who watched that Wanderers final are at an age where they could make their own name in the game, it's time to look at how young players are being developed.

The dilemma involving the development of young cricketers is simple. For batsmen, it's: do you concentrate on a method that provides hitting power and the capability of scoring at ten runs per over, or do you develop a solid foundation that allows for adjustment to any form of the game?

For a bowler it's even more straightforward: do you implant in his mind a metronomic desire to produce a string of dot balls, or a mentality that stresses the priority of wickets?

Having just witnessed a 40-year-old Michael Hussey shred a Big Bash League attack with a mixture of scorching off-drives, gentle taps to initiate a scampered single and four power-laden shots that cleared the boundary, I'd opt for the solid foundation method.

Hussey, along with a number of other fine batsmen from an era when players were brought up with success in the longer forms of the game as a measuring stick, is proof a solid all-round technique is easily adaptable to T20 cricket. The best T20 teams have a combination of batsmen who can survive and prosper against good bowling and those who regularly clear the boundary rope.

The ideal fast bowling blueprint is Dale Steyn, a bowler who combines an excellent strike rate with a relatively low economy rate. For spinners, R Ashwin is a good role model; he takes wickets at both ends of the batting order and keeps the long balls to a minimum.

The secret to good bowling is to keep believing you can dismiss a batsman. Once that thought turns to purely containment, the batsman is winning the battle.

Given reasonable pitches, the bowlers adapt well, but many batsmen struggle in anything other than serene conditions. On the evidence of the eye test and the average length of a Test, it's obvious that solid foundations are crumbling and most batsmen are ill-equipped to survive a searching test by a good bowler. This has been a recent trend but I don't see any attempt to alter the way batsmen are being developed.

I suspect batsmen are being over-coached and bombarded with theories in structured net sessions that often involve the dreaded bowling machine. There's a lot to be said for the old-fashioned method of simply advocating a solid defence and then encouraging a youngster to spend hours playing in match situations - either in the backyard or at the local park - in order to learn how his own game works best.

This method worked extremely well for batsmen as successful and diverse in style as Sir Garfield Sobers, Sachin Tendulkar and Greg Chappell. As Sobers says in his excellent coaching book: "One of the tragedies of cricket coaching is the greatness of the game's best players is revered but never followed."

It would be a good start for a budding young batsman to emulate the style and development process of a Tendulkar, a Hussey or an AB de Villiers. It would also help if the youngster avoided listening to coaches with theories on batting that haven't been proven in the middle. As former great Australian legspinner Bill O'Reilly once stated: "If you see a coach coming, son, run and hide behind a tree."

I'd modify that for a young batsman and say: "Seek good coaching or else avoid it at all costs and learn the game for yourself."

It's now eight years since Misbah-ul-Haq's ill-conceived attempted scoop shot ballooned to short fine leg at the Wanderers Stadium and India were crowned inaugural World T20 champions.

Much has happened in cricket since that exciting five-run victory and the bulk of it revolves around the evolution of T20. Leagues have sprung up like daisies in summer, with the IPL being the most affluent and gaudy, whilst the other two versions of the game - Test and 50-over cricket - have receded into the shadows.

Now that kids from all over the world who watched that Wanderers final are at an age where they could make their own name in the game, it's time to look at how young players are being developed.

The dilemma involving the development of young cricketers is simple. For batsmen, it's: do you concentrate on a method that provides hitting power and the capability of scoring at ten runs per over, or do you develop a solid foundation that allows for adjustment to any form of the game?

For a bowler it's even more straightforward: do you implant in his mind a metronomic desire to produce a string of dot balls, or a mentality that stresses the priority of wickets?

Having just witnessed a 40-year-old Michael Hussey shred a Big Bash League attack with a mixture of scorching off-drives, gentle taps to initiate a scampered single and four power-laden shots that cleared the boundary, I'd opt for the solid foundation method.

Hussey, along with a number of other fine batsmen from an era when players were brought up with success in the longer forms of the game as a measuring stick, is proof a solid all-round technique is easily adaptable to T20 cricket. The best T20 teams have a combination of batsmen who can survive and prosper against good bowling and those who regularly clear the boundary rope.

The ideal fast bowling blueprint is Dale Steyn, a bowler who combines an excellent strike rate with a relatively low economy rate. For spinners, R Ashwin is a good role model; he takes wickets at both ends of the batting order and keeps the long balls to a minimum.

The secret to good bowling is to keep believing you can dismiss a batsman. Once that thought turns to purely containment, the batsman is winning the battle.

Given reasonable pitches, the bowlers adapt well, but many batsmen struggle in anything other than serene conditions. On the evidence of the eye test and the average length of a Test, it's obvious that solid foundations are crumbling and most batsmen are ill-equipped to survive a searching test by a good bowler. This has been a recent trend but I don't see any attempt to alter the way batsmen are being developed.

I suspect batsmen are being over-coached and bombarded with theories in structured net sessions that often involve the dreaded bowling machine. There's a lot to be said for the old-fashioned method of simply advocating a solid defence and then encouraging a youngster to spend hours playing in match situations - either in the backyard or at the local park - in order to learn how his own game works best.

This method worked extremely well for batsmen as successful and diverse in style as Sir Garfield Sobers, Sachin Tendulkar and Greg Chappell. As Sobers says in his excellent coaching book: "One of the tragedies of cricket coaching is the greatness of the game's best players is revered but never followed."

It would be a good start for a budding young batsman to emulate the style and development process of a Tendulkar, a Hussey or an AB de Villiers. It would also help if the youngster avoided listening to coaches with theories on batting that haven't been proven in the middle. As former great Australian legspinner Bill O'Reilly once stated: "If you see a coach coming, son, run and hide behind a tree."

I'd modify that for a young batsman and say: "Seek good coaching or else avoid it at all costs and learn the game for yourself."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)