By Camila Ruz and Jon Kelly in BBC News Magazine

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesFloods have caused havoc across much of the UK. Have decisions made by the public and politicians alike made things worse?

Thousands of homes are without power after Storm Frank as people brace themselves for more flooding.

Dozens of flood warnings remain in place with north-east Scotland at risk of heavy rainfall on Sunday and Monday.

Here are some of the things that it has been suggested have contributed to the problem.

Building on flood plains

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesSome four million residential properties in England currently sit on places with a one in 1,000 risk of flooding each year.

After floods in 2007 that affected 55,000 homes, the government commissioned a review chaired by Sir Michael Pitt to ensure it didn't happen again. The review said it wasn't possible to prevent all building on floodplains but recommended that there should be a strong presumption against it. It also said buildings should avoid creating flood problems for themselves or their neighbours.

But large-scale building on floodplains has continued. In fact, according to the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), housing in areas where flooding is likely has grown at a rate of 1.2% per year since 2011, while the building of residential properties in areas of low risk has risen by just 0.7% over the same period.

Policy-makers are often keen to see brownfield land used for residential development, but these areas are often most vulnerable to flooding. Demand from buyers has fuelled this growth, too.

You might assume that there would be huge drops in property prices after highly publicised floods. But in places like Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire, and Cockermouth, Cumbria, which experienced heavy flooding in 2007 and 2009 respectively, prices have remained largely unaffected in the long run.

Dredging

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesThe argument over dredging has been going strong since floods in Somerset in 2013-14. At the time, farmers claimed that lack of river dredging had been making the problem worse. "Somerset is suffering from the impacts of two decades of underinvestment with the cessation of dredging along the lowland rivers Parrett and Tone," said the National Farmers Union in their Flooding Manifesto.

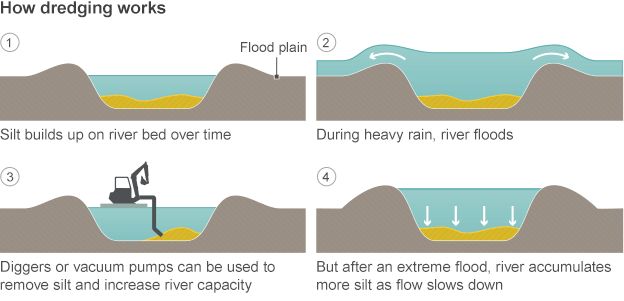

Dredging removes the silt that builds up at the bottom of rivers and deepens the channel. Some people say that it helps prevent flooding by making the water flow faster and more efficiently. Supporters of dredging have complained that the European Water Framework Directive prevents it being carried out.

But others have argued that it's not a good idea because the river can still be overwhelmed. When this happens it can cause faster and more dangerous floods downstream. "We've tended to straighten rivers, to canalise them, to embank them and all that rushes the water down to the nearby urban pinch point," explains environmentalist and writer George Monbiot, adding that the flow of water should be slowed down and the rivers lengthened instead.

River straightening

Image copyrightiStock

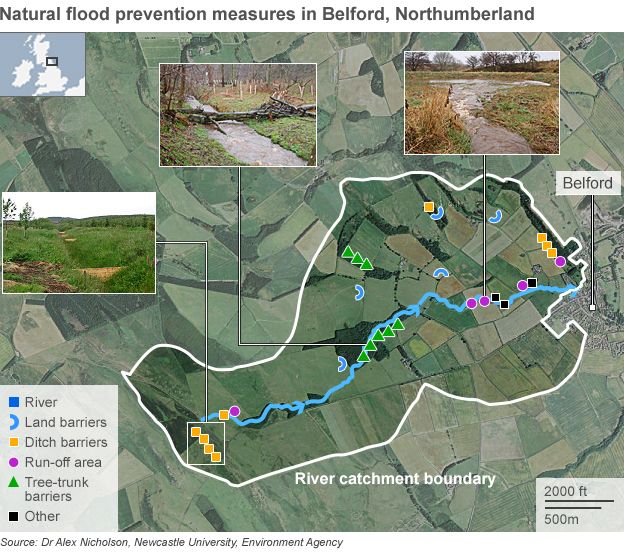

Image copyrightiStockOne way of encouraging a river to take its time in getting to its destination - and therefore reduce the risk of flooding - is to allow it to make large bends called meanders or to braid itself into a network of smaller channels. These twists and turns can help prevent flash floods from racing their way down at full force.

"There still has to be somewhere for that rain to go, you are not going to be able to hold it all back in the hills," explains Monbiot.

Reconnecting a river with its flood plain can also help prevent extreme events downstream. This allows the river to flood in certain areas, storing water in fields until it can be released slowly once the danger has passed. But this has to be controlled.

"If it's not managed carefully, obviously that flooding can have a serious impact on the farming business," says Rob Howells, the NFU's Water Quality Adviser. "The protection of the urban area has to be planned in conjunction with the protection of rural areas to make sure that everything is joined up and to make sure that you are not having unintended consequences elsewhere," he adds.

Destruction of upland habitats

Image copyrightScience Photo Library

Image copyrightScience Photo LibraryTrees can act as a natural flood defence. They have roots that reach deep into the soil, loosening it and allowing water to drain down more easily. A hillside covered in thick vegetation tends to release water more slowly than a bare hill. The compacted soil of farmland can also make the problem worse by reducing the ground's ability to hold water.

This is especially important upstream. Planting woodlands at a stream's upper reaches could help delay the water from reaching the main river. Trees can also end up providing small dams, although this needs to be managed with care.

Beavers would do this work for free, adds Monbiot. "They could be a very useful tool in preventing floods."

The Environment Agency has said that large areas of trees would need to be replanted for them to really make a difference. Flood defences on farmlands upstream might also not have had much effect in preventing the current flooding. "The levels of rainfall in the North West on already saturated ground were unprecedented," says a spokesman from the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). "It is unlikely flood protection on farmland would have made a material difference in such an exceptional flood."

Blanket bogs also play a key role in soaking up rainfall upstream. The peaty soil of a bog can be up to 90% water. Sphagnum mosses growing there can also hold water like a sponge. But many blanket bogs have been drained and their peat cut out which can increase the risk of flooding downstream.

Some people argue that there is not much incentive for farmers to keep land covered in thick vegetation because of EU rules. Land covered with "permanent ineligible features" such as ponds, dense scrub and some woodland can be disqualified from farm subsidies.

Woodland cover has increased in the UK since its lowest point during World War One but the UK is still one of the least wooded countries in Europe. "Planting trees can help to slow the flow of rivers and has an important role to play in reducing flood risk but they need to be located carefully to make sure that they are actually being beneficial," adds Howells.

Flood defences

Image copyrightGetty Images

Image copyrightGetty ImagesCritics have focused on the effectiveness of existing barriers. Carlisle's £38m flood-defence scheme was breached despite having been constructed only five years before, with an additional half-metre (1ft 8in) added on top to allow for the effects of climate change. There was anger at the decision to lift York's Foss Barrier, a key part of the city's flood defence system, because its pumps were at risk of electrical failure.

During its first year in office, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition announced it was cutting spending on flood defences by 8% compared with previous yearly spend - though the Environment Agency said at the time that the budget had actually been reduced by 27% in cash terms.

Critics have said reductions in maintenance budgets have worsened the problem. Judith Blake, the leader of Leeds City Council said there was a "north-south divide" in efforts to prevent flooding. She said the north of England had not seen "anywhere near the support that we saw going into Somerset", which flooded in 2014, and pointed out that the government had cut funding for a flood defence project in Leeds in 2011. She said there was now a "real anger growing across the North".

However, the prime minister said the government had spent more per head of the population on flood defences in the north than in the south and that £2.3bn would be spent on flood defences by 2020. The government has ordered a major review of flood prevention strategy.

A Defra spokeswoman said £1.7bn of investment into new or expanded flood defences in the previous parliament was an increase on spending from the previous administration. The spokeswoman added that a new six-year spending programme - replacing an annual bidding process for flood defence schemes - has allowed the government to make a long term commitment to protect the £171m spent each year on maintaining defences in real terms.

The concentration of Britons in urban areas - 82% live in towns and cities - has made them especially vulnerable to flooding because concrete surfaces, unlike soil, are almost completely impenetrable to water.

And even when new flood defences are built to protect homes in one area, there are complaints that they often simply cause flooding elsewhere. When the Berkshire town of Wraysbury flooded in 2014, residents said they were being used as "sacrificial lambs" to prevent Maidenhead from being flooded.

Climate change

Cameron has made a link between the floods and climate change. The government anticipates trends which have seen drier summers and wetter winters in the UK to continue. The UK Climate Projections of 2009 estimated a sea-level rise of between 13cm and 76cm for the UK by 2095.

The prime minister has said climate change is one of the biggest challenges the country faces and the government has announced plans for the UK's coal plants to be phased out within 10 years. The Environment Secretary recently announced a National Flood Resilience Review that would look again at flood risk, including the future impact of climate change.

Labour have said climate change should be treated as a national security issue and urged the government to do more. Environmental campaigners have criticisedministers for cutting support for green energy sources.

The climate change summit in Paris agreed a deal to attempt to limit the rise in global temperatures to less than 2C. However, Monbiot says "we have to take urgent action on climate change and go a lot further than the Paris agreement proposed".