Seismic risks for the global system are growing, not least worsening US geopolitical rivalries, climate change and now the coronavirus outbreak writes Nouriel Roubini in The Guardian

A swan fighting with crows on a beach. Photograph: Kamila Koziol/Alamy Stock Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

In my 2010 book, Crisis Economics, I defined financial crises not as the “black swan” events that Nassim Nicholas Taleb described in his eponymous bestseller but as “white swans”. According to Taleb, black swans are events that emerge unpredictably, like a tornado, from a fat-tailed statistical distribution. But I argued that financial crises, at least, are more like hurricanes: they are the predictable result of builtup economic and financial vulnerabilities and policy mistakes.

There are times when we should expect the system to reach a tipping point – the “Minsky Moment” – when a boom and a bubble turn into a crash and a bust. Such events are not about the “unknown unknowns” but rather the “known unknowns”.

Beyond the usual economic and policy risks that most financial analysts worry about, a number of potentially seismic white swans are visible on the horizon this year. Any of them could trigger severe economic, financial, political and geopolitical disturbances unlike anything since the 2008 crisis.

For starters, the US is locked in an escalating strategic rivalry with at least four implicitly aligned revisionist powers: China, Russia, Iran and North Korea. These countries all have an interest in challenging the US-led global order and 2020 could be a critical year for them, owing to the US presidential election and the potential change in US global policies that could follow.

Under Donald Trump, the US is trying to contain or even trigger regime change in these four countries through economic sanctions and other means. Similarly, the four revisionists want to undercut American hard and soft power abroad by destabilising the US from within through asymmetric warfare. If the US election descends into partisan rancour, chaos, disputed vote tallies and accusations of “rigged” elections, so much the better for rivals of the US. A breakdown of the US political system would weaken American power abroad.

Moreover, some countries have a particular interest in removing Trump. The acute threat that he poses to the Iranian regime gives it every reason to escalate the conflict with the US in the coming months – even if it means risking a full-scale war – on the chance that the ensuing spike in oil prices would crash the US stock market, trigger a recession, and sink Trump’s re-election prospects. Yes, the consensus view is that the targeted killing of Qassem Suleimani has deterred Iran but that argument misunderstands the regime’s perverse incentives. War between US and Iran is likely this year; the current calm is the one before the proverbial storm.

As for US-China relations, the recent phase one deal is a temporary Band-Aid. The bilateral cold war over technology, data, investment, currency and finance is already escalating sharply. The Covid-19 outbreak has reinforced the position of those in the US arguing for containment and lent further momentum to the broader trend of Sino-American “decoupling”. More immediately, the epidemic is likely to be more severe than currently expected and the disruption to the Chinese economy will have spillover effects on global supply chains – including pharma inputs, of which China is a critical supplier – and business confidence, all of which will likely be more severe than financial markets’ current complacency suggests.

Although the Sino-American cold war is by definition a low-intensity conflict, a sharp escalation is likely this year. To some Chinese leaders, it cannot be a coincidence that their country is simultaneously experiencing a massive swine flu outbreak, severe bird flu, a coronavirus outbreak, political unrest in Hong Kong, the re-election of Taiwan’s pro-independence president, and stepped-up US naval operations in the East and South China Seas. Regardless of whether China has only itself to blame for some of these crises, the view in Beijing is veering toward the conspiratorial.

But open aggression is not really an option at this point, given the asymmetry of conventional power. China’s immediate response to US containment efforts will likely take the form of cyberwarfare. There are several obvious targets. Chinese hackers (and their Russian, North Korean, and Iranian counterparts) could interfere in the US election by flooding Americans with misinformation and deep fakes. With the US electorate already so polarised, it is not difficult to imagine armed partisans taking to the streets to challenge the results, leading to serious violence and chaos.

Revisionist powers could also attack the US and western financial systems – including the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (Swift) platform. Already, the European Central Bank president, Christine Lagarde, has warned that a cyber-attack on European financial markets could cost $645bn (£496.2bn). And security officials have expressed similar concerns about the US, where an even wider range of telecommunication infrastructure is potentially vulnerable.

By next year, the US-China conflict could have escalated from a cold war to a near hot one. A Chinese regime and economy severely damaged by the Covid-19 crisis and facing restless masses will need an external scapegoat, and will likely set its sights on Taiwan, Hong Kong, Vietnam and US naval positions in the East and South China Seas; confrontation could creep into escalating military accidents. It could also pursue the financial “nuclear option” of dumping its holdings of US Treasury bonds if escalation does take place. Because US assets comprise such a large share of China’s (and, to a lesser extent, Russia’s) foreign reserves, the Chinese are increasingly worried that such assets could be frozen through US sanctions (like those already used against Iran and North Korea).

Of course, dumping US Treasuries would impede China’s economic growth if dollar assets were sold and converted back into renminbi (which would appreciate). But China could diversify its reserves by converting them into another liquid asset that is less vulnerable to US primary or secondary sanctions, namely gold. Indeed, China and Russia have been stockpiling gold reserves (overtly and covertly), which explains the 30% spike in gold prices since early 2019.

In a sell-off scenario, the capital gains on gold would compensate for any loss incurred from dumping US Treasuries, whose yields would spike as their market price and value fell. So far, China and Russia’s shift into gold has occurred slowly, leaving Treasury yields unaffected. But if this diversification strategy accelerates, as is likely, it could trigger a shock in the US Treasuries market, possibly leading to a sharp economic slowdown in the US.

The US, of course, will not sit idly by while coming under asymmetric attack. It has already been increasing the pressure on these countries with sanctions and other forms of trade and financial warfare, not to mention its own world-beating cyberwarfare capabilities. US cyber-attacks against the four rivals will continue to intensify this year, raising the risk of the first-ever cyber world war and massive economic, financial and political disorder.

Looking beyond the risk of severe geopolitical escalations in 2020, there are additional medium-term risks associated with climate change, which could trigger costly environmental disasters. Climate change is not just a lumbering giant that will cause economic and financial havoc decades from now. It is a threat in the here and now, as demonstrated by the growing frequency and severity of extreme weather events.

In addition to climate change, there is evidence that separate, deeper seismic events are under way, leading to rapid global movements in magnetic polarity and accelerating ocean currents. Any one of these developments could augur an environmental white swan event, as could climatic “tipping points” such as the collapse of major ice sheets in Antarctica or Greenland in the next few years. We already know that underwater volcanic activity is increasing; what if that trend translates into rapid marine acidification and the depletion of global fish stocks upon which billions of people rely?

As of early 2020, this is where we stand: the US and Iran have already had a military confrontation that will likely soon escalate; China is in the grip of a viral outbreak that could become a global pandemic; cyberwarfare is ongoing; major holders of US Treasuries are pursuing diversification strategies; the Democratic presidential primary is exposing rifts in the opposition to Trump and already casting doubt on vote-counting processes; rivalries between the US and four revisionist powers are escalating; and the real-world costs of climate change and other environmental trends are mounting.

This list is hardly exhaustive but it points to what one can reasonably expect for 2020. Financial markets, meanwhile, remain blissfully in denial of the risks, convinced that a calm if not happy year awaits major economies and global markets.

Wolfgang Munchau in The FT

When I think about the crisis of our liberal system, I am reminded of an encounter almost 20 years ago in Berlin with Wolfgang Kartte, a former president of the German cartel office. I asked why he and his successors often took such a conservative view on competition cases and in particular why they were so dismissive of economic arguments.

Like the majority of economic policymakers in Germany, Kartte, who died in 2003, was a lawyer. He said he considered his job as helping the little guy to defend himself against the big guy. This was the job of a lawyer, not of an economist. Moreover, he said he was not interested in levelling the playing field, as the metaphor goes, but in tilting it in favour of the little guy.

The crisis of modern liberalism has similar elements. We have our own version of the little guy versus the big guy problem today — except that there is no one to tilt the field in the other direction. Smaller companies pay more taxes relative to their income than large multinational corporations. The economic policies that followed the financial crisis ended up widening income and wealth differences. Large immigration flows created insecurity, as did the arrival of new technologies. When you call voters deplorable — or patronise them, as happened in the UK after the Brexit vote — you add insult to injury.

Kartte was an old-fashioned German ordoliberal, a school of thought that originated after the breakdown of German democracy in the early 1930s. The macroeconomics of German ordoliberalism is somewhat dodgy. But they excelled at one particular thing. Their intellectual leaders explained better than anyone else how the German liberal order of the 1920s collapsed and how it drove a majority of the population away from supporting it.

The short, flippant answer is that the Weimar Republic favoured the big guy. The macroeconomic shocks of the period — hyperinflation and depression — are well understood. They contributed to a large extent to the political alienation of the middle classes. But they were not the only causes. The period also saw an increase in industrial cartels that threatened the livelihoods of small merchants and entrepreneurs.

When the ordoliberals finally came to power in postwar Germany, they began by tilting the playing field in the other direction by creating a corporate and financial infrastructure to support small and medium-sized companies. Germany’s Mittelstand is both a reason for German robustness, but also for stagnation. And one of the main lessons of modern economic history is we cannot be oblivious to the distribution of income and wealth.

This is not an argument about redistribution. This is about actively managing capitalism’s playing field to ensure that the majority of the population stays on it. Recall Margaret Thatcher’s successful brand of entrepreneurial capitalism in the UK in the 1980s. Through privatisation, she turned ordinary savers into shareholders. Through the sale of council houses, she turned tenants into property owners.

We cannot replicate this example: there are no council houses to be sold, nor companies to be privatised. But to save modern capitalism we will need to find ways to keep the median voter committed to the system, just as Thatcher did in the 1980s. I would argue that voters are still broadly content in places such as Germany, the Benelux countries and in Ireland. I am less sure about the UK, France or Italy.

What often leads the supporters and defenders of modern liberal democracy astray in their analysis is their addiction to macroeconomic aggregate variables such as gross domestic product and the officially recorded rate of unemployment. The decade before the Brexit referendum was a decade of reasonable GDP growth. There was nothing in the data that would suggest the UK would vote to leave the EU. But granular information paints a different picture. Data based on the official family resources survey and from the Resolution Foundation, a think-tank, showed household income after housing costs stagnated for the 60 per cent of households towards the bottom of the income distribution between 2002 and 2015.

The current wave of discontent in France also contrasts with relatively solid GDP growth since the financial crisis. But a study by the McKinsey Global Institute showed that income growth came to an abrupt halt for almost all households in the advanced economies.

The main constituency backing the Thatcher revolution in the 1980s was the C2s — the demographic classification for skilled working class people. Thatcher looked after the median household. Her successors first lost the middle classes, and then pretended to be shocked by events such as Brexit.

Any system that leaves behind 60 per cent of households will eventually fail. It is the ultimate irony: liberalism is failing because of market forces.

Seven decades of prosperity have lulled the UK into thinking we’re special – that disasters only happen to other people writes David Bennun in The Guardian

Keeping calm in Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire: ‘The idea that we’re protected, we’re exceptional, is not articulated … but it’s there.’ Photograph: JOHN ROBERTSON

Most British people don’t have the first inkling of what a crisis is. They think it’s a political thing. “Government in crisis”, and so on. Whatever happens at the top, life will go on as ever. There will be food in the shops, medical supplies in the hospitals, water in the taps and order on the streets (as much as there usually is). Anyone who warns you otherwise is a catastrophist, a drama queen, a scaremonger, a Cassandra.

That’s what a seven-decade period of general peace and collective prosperity does for you. It makes you think it’s normal, rather than a hard-won, fragile rarity in history. It makes most people complacent, and turns a small but unfortunately influential number into the kind of adolescent romantics who think you can smash up everything in the house and stick two fingers up to Mummy and Daddy because, no matter what you do, they will always be there to make it right in the end. Mummy and Daddy won’t let anything too bad happen to us.

The idea that we’re protected, we’re exceptional, is not articulated or usually even conscious. But it’s there. That this is who we are. Disaster – mass, national disaster – happens to other people, in other places.

But there is no such rule. No such guarantee. Mummy and Daddy won’t always come to bail us out. And if you’ve ever lived in one of those other places, chances are you will have seen how quickly what you thought was an orderly society can disintegrate under pressure. If you’ve never known gunfire and mobs on the streets, or empty taps and empty shelves, or power that’s off more than it’s on, or morgues full of the victims of racial, political or tribal violence, you don’t have a clue how easily that can happen.

I experienced all these things when I was growing up in Kenya. Some were routine; the more severe, mercifully less so. Branded on my memory from an attempted coup d’état in 1982 is the sound of automatic rifle fire along the road; the crowds surging like waves; confusion and misinformation crackling from the radio; most of all, hearing the account of my late father, a doctor, of the aftermath of what I can best describe as a pogrom, unleashed by the breakdown of order, against the Asian people of Nairobi, his hospital full of the dead and grievously wounded people, many of them children no older than I was.

All the talk of “Blitz spirit” comes from people who have never known what it is to truly fear everything crashing down

Britain is not Kenya. It is, in the ordinary run of things, much better protected against such convulsions than a country such as Kenya. But do away with the ordinary run of things, and any place in the world can suffer as Kenya did then. You don’t have to look too far back at European history to see it, nor do you have to look away from home. The British people I know who most swiftly grasped and vividly understood the implications of present events as they began to unfold are Northern Irish. There’s a reason for that.

Democratic institutions, the rule of law, civic infrastructure, a culture of local and national governance in which corruption, while ever present, is exceptional rather than institutional: these things, flawed as they may be and ever improvable as they are, take generations, even centuries to build. But once they topple, they can topple at terrifying speed and with terrifying effect. Britain has forgotten what that’s like.

All the talk about the “Blitz spirit” comes from people who have never known what it is to truly fear everything crashing down around you. In liberal democracies enthusiasm for a revolution usually comes from people who have known nothing but the safety and freedom of the “system” – which is to say the imperfect protective structure – that they abhor. Talk to anyone who has experienced the glories of such upheaval and they are generally not quite so keen on it.

To be, politically speaking, a grownup is something to be sneered at these days. It means you’re lacking in imagination, in boldness of vision, in belief in a better country or a better world. That’s a view held invariably by people who would, without grownups running things, have been lucky to survive long enough to articulate it. Similarly, a contempt for expertise is inevitably expressed by those who, without experts contributing to society as they do, would be lucky to have a voice to speak with, let alone a platform on which to use it. Expertise, like democracy, is far from infallible; each, however, is always preferable to the alternative.

When the grownups fail, as they periodically do, and badly, what you need is better grownups. Awful things have happened, and do happen, in this country, chiefly as a result of bad policy and worse enactment. We don’t need to have homelessness, dependency on food banks or deprived areas ruled by criminals and bullies. We can afford to act against these evils, but we let them happen all the same. That shames us. Hand the keys and the controls over to eternal teenagers – populists of either stripe – and what you’ll get is a situation where that choice is gone.

We’re not special. If, in a deluded fit of national self-harm that ever more resembles the drift into war in 1914, we allow ourselves to wreck the complicated machinery that underpins our everyday lives without us ever having to think much about it, nobody will be coming to rescue us. Cassandra, as Cassandras are always ready to remind you, was right.

Shahid Mehmood in The Friday Times

When the economic recession of 2008 struck the world economy, not many would have guessed that this event would set off a wave of serious introspection about the nature and morality of present day capitalism. Many, including economists, thought that this is just a continuation of the traditional cycle that an economy goes through, whereby periods of growth are followed by recessions (which in general means lower GDP growth rates). It was expected that things would be back to normal within a few years.

But something different transpired this time around. Millions of people around the globe, especially in the leading centers of global capitalism like London and New York, spilled onto the streets and vented their anger against the present state of capitalism. This movement became the ‘Wall Street vs Main Street’ movement. Many years down the line, the world economy (mainly the industrialised world) is yet to regain its growth trajectory and the waves generated by the movement still reverberate. In effect, what we have is a crisis of the workings of capitalism. It would be interesting to delve into some details in order to understand how this state of affairs came to be?

This discussion takes us back to a Scottish professor of moral philosophy and his writings on market economy and capitalism. Adam Smith, who is now revered as the father of economics, wrote his magnum opus Wealth of Nations (WON) in 1776. Considered the bible of economics, one of the most outstanding insights of the book was that a person’s greed ends up benefitting the community as a whole. Two sentences (abbreviated) lay out this principle; Smith contends that: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest…” and “Every individual… neither intends to promote the public interest nor knows how much he is promoting it… he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention”.

Smith’s workings of an efficient capitalist system is tied to the workings of the ‘invisible hand’, the famous concept which explains how greed that ends up promoting the greater good. But the most noticeable aspect of this concept is that Smith first mentioned it in an equally remarkable (though less discussed) book of his called the Theory of Moral Sentiments. Published before WON, it outlined the moral pre-requisites for an economy to function properly. Smith’s concept of the invisible hand, therefore, was closely tied to morality. It reads as follows: “[The rich] consume little more than the poor and in spite of their natural selfishness and rapacity…they divide with the poor the produce of all their improvements. They are led by an invisible hand to make nearly the same distribution of the necessaries of life …”

What Smith envisioned has, up till the end of 20th century, worked pretty well. What we saw in the industrialised nations was that capitalists and entrepreneurs, in pursuit of profit, implemented ventures and projects that ended up benefiting the society as a whole. Setting up a plant for production, for example, was purely done for personal gain. But the venture needed employees, and thus many aspiring job seekers found their sustenance due to the pursuit of greed by the industrialists/capitalists. Gradually, in the face of rising resistance in the form of Marx and others, the economies of nation states gradually transformed into welfare states, whose main beneficiaries were the larger, lower segments of the population and the middle classes. This setting worked remarkably well, and explains how it managed to weather stiff resistance over centuries, none bigger than Communism which met its demise in 1991 with the dismemberment of the Soviet Union.

But the 21st century has seen the consensus starting to unravel, with the Wall Street vs Main Street only the first sign of widespread consternation. And the simple reason is that the workings of the invisible hand are now skewed starkly in favour of the one percent.

The signs of this dysfunction are all around, in numbers and other instances. All around the world, labour’s share of total national income is on a constant decline. The real income (income adjusted for the cost of living), except for top percentile of earners, has been falling gradually. Income inequality is at a historic high. Credit Suisse, which tracks global wealth, estimated that the richest one percent now own half of total global wealth (estimated at $280 trillion).

The 18th, 19th and 20th century witnessed entrepreneurship and capitalism in a manner that every new venture resulted in creation of newer job opportunities, generation of real wealth and comparatively proportionate distribution of wealth. In contrast, today’s wealth creation is largely centered upon financial engineering and application of technological developments. The former is merely a transfer of wealth from the lower percentiles (poor and middle classes) to the rich, and the latter is leading to lesser need for workers as artificial intelligence (AI) does the work without requiring any benefits (wages, health insurance, etc.) and thus saving the owners/entrepreneurs major costs of operating a venture. The global economic scene was once dominated by companies like GM that employed thousands of people. Now, it’s dominated by organisations like Google and Amazon whose quantum of wealth is much larger, yet they employ not even half of the labour employed by big players of yesteryears. Facebook, for example, has a market cap of $370 billion, yet employs no more than 14,000 people.

What factors drive this concentration of wealth? The main culprit, apart from others like government regulations, is technology, especially software and AI. Today’s technology has this extraordinary feature that only a small initial investment is needed to make the first software copy, but the millions following it can be replicated at zero cost. Thus, the owner can earn billions without the need to invest further. In technical lingo, there is zero marginal cost of replication, which makes all this different from yesteryears. These technologies do produce jobs, but these are ‘gigs’ rather than good, quality jobs with financial security. And they pay little, usually sustenance level wages except for technically exceptional people. This means that majority of workforce is already out of contention for good, high-paying jobs, thus contributing towards the labour’s falling share of national income.

The anger of Main Street is understandable. Today’s capitalism delivers wealth in the hands of a few. Those responsible for all those Ponzi schemes that destroyed the hard-earned savings of the working class have largely gone scot-free (too big to fail phenomena). And today’s global economic scene has a heavy imprint of rent-seekers, tax dodgers and financial wizards who do not contribute much to the well-being of the citizens or the real economy. This situation aptly describes the challenge faced by Capitalism. A system that has been exceptional in delivering prosperity and successfully warding off challenges over time now finds itself under severe scrutiny because its underlying mechanism of shared prosperity has, to a large extent, stopped working. Not surprisingly, as the dreams of shared prosperity recede, so does the moral ground for its continuation.

Yanis Varoufakis in The Guardian

For a manifesto to succeed, it must speak to our hearts like a poem while infecting the mind with images and ideas that are dazzlingly new. It needs to open our eyes to the true causes of the bewildering, disturbing, exciting changes occurring around us, exposing the possibilities with which our current reality is pregnant. It should make us feel hopelessly inadequate for not having recognised these truths ourselves, and it must lift the curtain on the unsettling realisation that we have been acting as petty accomplices, reproducing a dead-end past. Lastly, it needs to have the power of a Beethoven symphony, urging us to become agents of a future that ends unnecessary mass suffering and to inspire humanity to realise its potential for authentic freedom.

No manifesto has better succeeded in doing all this than the one published in February 1848 at 46 Liverpool Street, London. Commissioned by English revolutionaries, The Communist Manifesto (or the Manifesto of the Communist Party, as it was first published) was authored by two young Germans – Karl Marx, a 29-year-old philosopher with a taste for epicurean hedonism and Hegelian rationality, and Friedrich Engels, a 28-year-old heir to a Manchester mill.

As a work of political literature, the manifesto remains unsurpassed. Its most infamous lines, including the opening one (“A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of communism”), have a Shakespearean quality. Like Hamlet confronted by the ghost of his slain father, the reader is compelled to wonder: “Should I conform to the prevailing order, suffering the slings and arrows of the outrageous fortune bestowed upon me by history’s irresistible forces? Or should I join these forces, taking up arms against the status quo and, by opposing it, usher in a brave new world?”

For Marx and Engels’ immediate readership, this was not an academic dilemma, debated in the salons of Europe. Their manifesto was a call to action, and heeding this spectre’s invocation often meant persecution, or, in some cases, lengthy imprisonment. Today, a similar dilemma faces young people: conform to an established order that is crumbling and incapable of reproducing itself, or oppose it, at considerable personal cost, in search of new ways of working, playing and living together? Even though communist parties have disappeared almost entirely from the political scene, the spirit of communism driving the manifesto is proving hard to silence.

To see beyond the horizon is any manifesto’s ambition. But to succeed as Marx and Engels did in accurately describing an era that would arrive a century-and-a-half in the future, as well as to analyse the contradictions and choices we face today, is truly astounding. In the late 1840s, capitalism was foundering, local, fragmented and timid. And yet Marx and Engels took one long look at it and foresaw our globalised, financialised, iron-clad, all-singing-all-dancing capitalism. This was the creature that came into being after 1991, at the very same moment the establishment was proclaiming the death of Marxism and the end of history.

Of course, the predictive failure of The Communist Manifesto has long been exaggerated. I remember how even leftwing economists in the early 1970s challenged the pivotal manifesto prediction that capital would “nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere”. Drawing upon the sad reality of what were then called third world countries, they argued that capital had lost its fizz well before expanding beyond its “metropolis” in Europe, America and Japan.

Empirically they were correct: European, US and Japanese multinational corporations operating in the “peripheries” of Africa, Asia and Latin America were confining themselves to the role of colonial resource extractors and failing to spread capitalism there. Instead of imbuing these countries with capitalist development (drawing “all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilisation”), they argued that foreign capital was reproducing the development of underdevelopment in the third world. It was as if the manifesto had placed too much faith in capital’s ability to spread into every nook and cranny. Most economists, including those sympathetic to Marx, doubted the manifesto’s prediction that “exploitation of the world-market” would give “a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country”.

As it turned out, the manifesto was right, albeit belatedly. It would take the collapse of the Soviet Union and the insertion of two billion Chinese and Indian workers into the capitalist labour market for its prediction to be vindicated. Indeed, for capital to globalise fully, the regimes that pledged allegiance to the manifesto had first to be torn asunder. Has history ever procured a more delicious irony?

Anyone reading the manifesto today will be surprised to discover a picture of a world much like our own, teetering fearfully on the edge of technological innovation. In the manifesto’s time, it was the steam engine that posed the greatest challenge to the rhythms and routines of feudal life. The peasantry were swept into the cogs and wheels of this machinery and a new class of masters, the factory owners and the merchants, usurped the landed gentry’s control over society. Now, it is artificial intelligence and automation that loom as disruptive threats, promising to sweep away “all fixed, fast-frozen relations”. “Constantly revolutionising … instruments of production,” the manifesto proclaims, transform “the whole relations of society”, bringing about “constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation”.

Composite: Guardian Design

For Marx and Engels, however, this disruption is to be celebrated. It acts as a catalyst for the final push humanity needs to do away with our remaining prejudices that underpin the great divide between those who own the machines and those who design, operate and work with them. “All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned,” they write in the manifesto of technology’s effect, “and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind”. By ruthlessly vaporising our preconceptions and false certainties, technological change is forcing us, kicking and screaming, to face up to how pathetic our relations with one another are.

Today, we see this reckoning in millions of words, in print and online, used to debate globalisation’s discontents. While celebrating how globalisation has shifted billions from abject poverty to relative poverty, venerable western newspapers, Hollywood personalities, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, bishops and even multibillionaire financiers all lament some of its less desirable ramifications: unbearable inequality, brazen greed, climate change, and the hijacking of our parliamentary democracies by bankers and the ultra-rich.

None of this should surprise a reader of the manifesto. “Society as a whole,” it argues, “is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other.” As production is mechanised, and the profit margin of the machine-owners becomes our civilisation’s driving motive, society splits between non-working shareholders and non-owner wage-workers. As for the middle class, it is the dinosaur in the room, set for extinction.

At the same time, the ultra-rich become guilt-ridden and stressed as they watch everyone else’s lives sink into the precariousness of insecure wage-slavery. Marx and Engels foresaw that this supremely powerful minority would eventually prove “unfit to rule” over such polarised societies, because they would not be in a position to guarantee the wage-slaves a reliable existence. Barricaded in their gated communities, they find themselves consumed by anxiety and incapable of enjoying their riches. Some of them, those smart enough to realise their true long-term self-interest, recognise the welfare state as the best available insurance policy. But alas, explains the manifesto, as a social class, it will be in their nature to skimp on the insurance premium, and they will work tirelessly to avoid paying the requisite taxes.

Is this not what has transpired? The ultra-rich are an insecure, permanently disgruntled clique, constantly in and out of detox clinics, relentlessly seeking solace from psychics, shrinks and entrepreneurial gurus. Meanwhile, everyone else struggles to put food on the table, pay tuition fees, juggle one credit card for another or fight depression. We act as if our lives are carefree, claiming to like what we do and do what we like. Yet in reality, we cry ourselves to sleep.

Do-gooders, establishment politicians and recovering academic economists all respond to this predicament in the same way, issuing fiery condemnations of the symptoms (income inequality) while ignoring the causes (exploitation resulting from the unequal property rights over machines, land, resources). Is it any wonder we are at an impasse, wallowing in hopelessness that only serves the populists seeking to court the worst instincts of the masses?

With the rapid rise of advanced technology, we are brought closer to the moment when we must decide how to relate to each other in a rational, civilised manner. We can no longer hide behind the inevitability of work and the oppressive social norms it necessitates. The manifesto gives its 21st-century reader an opportunity to see through this mess and to recognise what needs to be done so that the majority can escape from discontent into new social arrangements in which “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all”. Even though it contains no roadmap of how to get there, the manifesto remains a source of hope not to be dismissed.

If the manifesto holds the same power to excite, enthuse and shame us that it did in 1848, it is because the struggle between social classes is as old as time itself. Marx and Engels summed this up in 13 audacious words: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

From feudal aristocracies to industrialised empires, the engine of history has always been the conflict between constantly revolutionising technologies and prevailing class conventions. With each disruption of society’s technology, the conflict between us changes form. Old classes die out and eventually only two remain standing: the class that owns everything and the class that owns nothing – the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

This is the predicament in which we find ourselves today. While we owe capitalism for having reduced all class distinctions to the gulf between owners and non-owners, Marx and Engels want us to realise that capitalism is insufficiently evolved to survive the technologies it spawns. It is our duty to tear away at the old notion of privately owned means of production and force a metamorphosis, which must involve the social ownership of machinery, land and resources. Now, when new technologies are unleashed in societies bound by the primitive labour contract, wholesale misery follows. In the manifesto’s unforgettable words: “A society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells.”

The sorcerer will always imagine that their apps, search engines, robots and genetically engineered seeds will bring wealth and happiness to all. But, once released into societies divided between wage labourers and owners, these technological marvels will push wages and prices to levels that create low profits for most businesses. It is only big tech, big pharma and the few corporations that command exceptionally large political and economic power over us that truly benefit. If we continue to subscribe to labour contracts between employer and employee, then private property rights will govern and drive capital to inhuman ends. Only by abolishing private ownership of the instruments of mass production and replacing it with a new type of common ownership that works in sync with new technologies, will we lessen inequality and find collective happiness.

According to Marx and Engels’ 13-word theory of history, the current stand-off between worker and owner has always been guaranteed. “Equally inevitable,” the manifesto states, is the bourgeoisie’s “fall and the victory of the proletariat”. So far, history has not fulfilled this prediction, but critics forget that the manifesto, like any worthy piece of propaganda, presents hope in the form of certainty. Just as Lord Nelson rallied his troops before the Battle of Trafalgar by announcing that England “expected” them to do their duty (even if he had grave doubts that they would), the manifesto bestows upon the proletariat the expectation that they will do their duty to themselves, inspiring them to unite and liberate one another from the bonds of wage-slavery.

Will they? On current form, it seems unlikely. But, then again, we had to wait for globalisation to appear in the 1990s before the manifesto’s estimation of capital’s potential could be fully vindicated. Might it not be that the new global, increasingly precarious proletariat needs more time before it can play the historic role the manifesto anticipated? While the jury is still out, Marx and Engels tell us that, if we fear the rhetoric of revolution, or try to distract ourselves from our duty to one another, we will find ourselves caught in a vertiginous spiral in which capital saturates and bleaches the human spirit. The only thing we can be certain of, according to the manifesto, is that unless capital is socialised we are in for dystopic developments.

On the topic of dystopia, the sceptical reader will perk up: what of the manifesto’s own complicity in legitimising authoritarian regimes and steeling the spirit of gulag guards? Instead of responding defensively, pointing out that no one blames Adam Smith for the excesses of Wall Street, or the New Testament for the Spanish Inquisition, we can speculate how the authors of the manifesto might have answered this charge. I believe that, with the benefit of hindsight, Marx and Engels would confess to an important error in their analysis: insufficient reflexivity. This is to say that they failed to give sufficient thought, and kept a judicious silence, over the impact their own analysis would have on the world they were analysing.

The manifesto told a powerful story in uncompromising language, intended to stir readers from their apathy. What Marx and Engels failed to foresee was that powerful, prescriptive texts have a tendency to procure disciples, believers – a priesthood, even – and that this faithful might use the power bestowed upon them by the manifesto to their own advantage. With it, they might abuse other comrades, build their own power base, gain positions of influence, bed impressionable students, take control of the politburo and imprison anyone who resists them.

Similarly, Marx and Engels failed to estimate the impact of their writing on capitalism itself. To the extent that the manifesto helped fashion the Soviet Union, its eastern European satellites, Castro’s Cuba, Tito’s Yugoslavia and several social democratic governments in the west, would these developments not cause a chain reaction that would frustrate the manifesto’s predictions and analysis? After the Russian revolution and then the second world war, the fear of communism forced capitalist regimes to embrace pension schemes, national health services, even the idea of making the rich pay for poor and petit bourgeois students to attend purpose-built liberal universities. Meanwhile, rabid hostility to the Soviet Union stirred up paranoia and created a climate of fear that proved particularly fertile for figures such as Joseph Stalin and Pol Pot.

I believe that Marx and Engels would have regretted not anticipating the manifesto’s impact on the communist parties it foreshadowed. They would be kicking themselves that they overlooked the kind of dialectic they loved to analyse: how workers’ states would become increasingly totalitarian in their response to capitalist state aggression, and how, in their response to the fear of communism, these capitalist states would grow increasingly civilised.

Blessed, of course, are the authors whose errors result from the power of their words. Even more blessed are those whose errors are self-correcting. In our present day, the workers’ states inspired by the manifesto are almost gone, and the communist parties disbanded or in disarray. Liberated from competition with regimes inspired by the manifesto, globalised capitalism is behaving as if it is determined to create a world best explained by the manifesto.

What makes the manifesto truly inspiring today is its recommendation for us in the here and now, in a world where our lives are being constantly shaped by what Marx described in his earlier Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts as “a universal energy which breaks every limit and every bond and posits itself as the only policy, the only universality, the only limit and the only bond”. From Uber drivers and finance ministers to banking executives and the wretchedly poor, we can all be excused for feeling overwhelmed by this “energy”. Capitalism’s reach is so pervasive it can sometimes seem impossible to imagine a world without it. It is only a small step from feelings of impotence to falling victim to the assertion there is no alternative. But, astonishingly (claims the manifesto), it is precisely when we are about to succumb to this idea that alternatives abound.

What we don’t need at this juncture are sermons on the injustice of it all, denunciations of rising inequality or vigils for our vanishing democratic sovereignty. Nor should we stomach desperate acts of regressive escapism: the cry to return to some pre-modern, pre-technological state where we can cling to the bosom of nationalism. What the manifesto promotes in moments of doubt and submission is a clear-headed, objective assessment of capitalism and its ills, seen through the cold, hard light of rationality.

Composite: Guardian Design

The manifesto argues that the problem with capitalism is not that it produces too much technology, or that it is unfair. Capitalism’s problem is that it is irrational. Capital’s success at spreading its reach via accumulation for accumulation’s sake is causing human workers to work like machines for a pittance, while the robots are programmed to produce stuff that the workers can no longer afford and the robots do not need. Capital fails to make rational use of the brilliant machines it engenders, condemning whole generations to deprivation, a decrepit environment, underemployment and zero real leisure from the pursuit of employment and general survival. Even capitalists are turned into angst-ridden automatons. They live in permanent fear that unless they commodify their fellow humans, they will cease to be capitalists – joining the desolate ranks of the expanding precariat-proletariat.

If capitalism appears unjust it is because it enslaves everyone, rich and poor, wasting human and natural resources. The same “production line” that pumps out untold wealth also produces deep unhappiness and discontent on an industrial scale. So, our first task – according to the manifesto – is to recognise the tendency of this all-conquering “energy” to undermine itself.

When asked by journalists who or what is the greatest threat to capitalism today, I defy their expectations by answering: capital! Of course, this is an idea I have been plagiarising for decades from the manifesto. Given that it is neither possible nor desirable to annul capitalism’s “energy”, the trick is to help speed up capital’s development (so that it burns up like a meteor rushing through the atmosphere) while, on the other hand, resisting (through rational, collective action) its tendency to steamroller our human spirit. In short, the manifesto’s recommendation is that we push capital to its limits while limiting its consequences and preparing for its socialisation.

We need more robots, better solar panels, instant communication and sophisticated green transport networks. But equally, we need to organise politically to defend the weak, empower the many and prepare the ground for reversing the absurdities of capitalism. In practical terms, this means treating the idea that there is no alternative with the contempt it deserves while rejecting all calls for a “return” to a less modernised existence. There was nothing ethical about life under earlier forms of capitalism. TV shows that massively invest in calculated nostalgia, such as Downton Abbey, should make us glad to live when we do. At the same time, they might also encourage us to floor the accelerator of change.

The manifesto is one of those emotive texts that speak to each of us differently at different times, reflecting our own circumstances. Some years ago, I called myself an erratic, libertarian Marxist and I was roundly disparaged by non-Marxists and Marxists alike. Soon after, I found myself thrust into a political position of some prominence, during a period of intense conflict between the then Greek government and some of capitalism’s most powerful agents. Rereading the manifesto for the purposes of writing this introduction has been a little like inviting the ghosts of Marx and Engels to yell a mixture of censure and support in my ear.

Adults in the Room, my memoir of the time I served as Greece’s finance minister in 2015, tells the story of how the Greek spring was crushed via a combination of brute force (on the part of Greece’s creditors) and a divided front within my own government. It is as honest and accurate as I could make it. Seen from the perspective of the manifesto, however, the true historical agents were confined to cameo appearances or to the role of quasi-passive victims. “Where is the proletariat in your story?” I can almost hear Marx and Engels screaming at me now. “Should they not be the ones confronting capitalism’s most powerful, with you supporting from the sidelines?”

Thankfully, rereading the manifesto has offered some solace too, endorsing my view of it as a liberal text – a libertarian one, even. Where the manifesto lambasts bourgeois-liberal virtues, it does so because of its dedication and even love for them. Liberty happiness, autonomy, individuality, spirituality, self-guided development are ideals that Marx and Engels valued above everything else. If they are angry with the bourgeoisie, it is because the bourgeoisie seeks to deny the majority any opportunity to be free. Given Marx and Engels’ adherence to Hegel’s fantastic idea that no one is free as long as one person is in chains, their quarrel with the bourgeoisie is that they sacrifice everybody’s freedom and individuality on capitalism’s altar of accumulation.

Although Marx and Engels were not anarchists, they loathed the state and its potential to be manipulated by one class to suppress another. At best, they saw it as a necessary evil that would live on in the good, post-capitalist future coordinating a classless society. If this reading of the manifesto holds water, the only way of being a communist is to be a libertarian one. Heeding the manifesto’s call to “Unite!” is in fact inconsistent with becoming card-carrying Stalinists or with seeking to remake the world in the image of now-defunct communist regimes.

When everything is said and done, then, what is the bottom line of the manifesto? And why should anyone, especially young people today, care about history, politics and the like?

Marx and Engels based their manifesto on a touchingly simple answer: authentic human happiness and the genuine freedom that must accompany it. For them, these are the only things that truly matter. Their manifesto does not rely on strict Germanic invocations of duty, or appeals to historic responsibilities to inspire us to act. It does not moralise, or point its finger. Marx and Engels attempted to overcome the fixations of German moral philosophy and capitalist profit motives, with a rational, yet rousing appeal to the very basics of our shared human nature.

Key to their analysis is the ever-expanding chasm between those who produce and those who own the instruments of production. The problematic nexus of capital and waged labour stops us from enjoying our work and our artefacts, and turns employers and workers, rich and poor, into mindless, quivering pawns who are being quick-marched towards a pointless existence by forces beyond our control.

But why do we need politics to deal with this? Isn’t politics stultifying, especially socialist politics, which Oscar Wilde once claimed “takes up too many evenings”? Marx and Engels’ answer is: because we cannot end this idiocy individually; because no market can ever emerge that will produce an antidote to this stupidity. Collective, democratic political action is our only chance for freedom and enjoyment. And for this, the long nights seem a small price to pay.

Humanity may succeed in securing social arrangements that allow for “the free development of each” as the “condition for the free development of all”. But, then again, we may end up in the “common ruin” of nuclear war, environmental disaster or agonising discontent. In our present moment, there are no guarantees. We can turn to the manifesto for inspiration, wisdom and energy but, in the end, what prevails is up to us.

Pankaj Mishra in The Guardian

On the evening of 30 January 1948, five months after the independence and partition of India, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was walking to a prayer meeting at his temporary home in New Delhi when he was shot three times, at point-blank range. He collapsed and died instantly. His assassin, originally feared to be Muslim, turned out to be Nathuram Godse, a Hindu Brahmin from western India. Godse, who made no attempt to escape, said in court that he felt compelled to kill Gandhi since the leader with his womanly politics was emasculating the Hindu nation – in particular, with his generosity to Muslims. Godse is a hero today in an India utterly transformed by Hindu chauvinists – an India in which Mein Kampf is a bestseller, a political movement inspired by European fascists dominates politics and culture, and Narendra Modi, a Hindu supremacist accused of mass murder, is prime minister. For all his talk of Hindu genius, Godse flagrantly plagiarised the fictions of European ethnic-racial chauvinists and imperialists. For the first years of his life he was raised as a girl, with a nose ring, and later tried to gain a hard-edged masculine identity through Hindu supremacism. Yet for many struggling young Indians today Godse represents, along with Adolf Hitler, a triumphantly realised individual and national manhood.

The moral prestige of Gandhi’s murderer is only one sign among many of what seems to be a global crisis of masculinity. Luridly retro ideas of what it means to be a strong man have gone mainstream even in so-called advanced nations. In January Jordan B Peterson, a Canadian self-help writer who laments that “the west has lost faith in masculinity” and denounces the “murderous equity doctrine” espoused by women, was hailed in the New York Times as “the most influential public intellectual in the western world right now”.

‘The west has lost faith in masculinity’ … self-help writer Jordan Peterson. Photograph: Carlos Osorio/Toronto Star via Getty Images

This is, hopefully, an exaggeration. It is arguable, however, that a frenetic pursuit of masculinity has characterised public life in the west since 9/11; and it presaged the serial-groping president who boasts of his big penis and nuclear button. “From the ashes of September 11,” the Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan exulted a few weeks after the attack, “arise the manly virtues.” Noonan, who today admires Peterson’s “tough” talk, hailed the re-emergence of “masculine men, men who push things and pull things”, such as George W Bush, who she half expected to “tear open his shirt and reveal the big ‘S’ on his chest”. Such gush, commonplace at the time, helped Bush, who had initially gone missing in action on 11 September, reinvent himself as a dashing commander-in-chief (and grow cocky enough to dress up as a fighter pilot and compliment Tony Blair’s “cojones”).

Amid this rush of testosterone in the Anglo-American establishment, many deskbound journalists fancied themselves as unflinching warriors. “We will,” David Brooks, another of Peterson’s fans, vowed, “destroy innocent villages by accident, shrug our shoulders and continue fighting.”

As manly virtues arose, attacks on women, and feminists in particular, in the west became nearly as fierce as the wars waged abroad to rescue Muslim damsels in distress. In Manliness (2006) Harvey Mansfield, a political philosopher at Harvard, denounced working women for undermining the protective role of men. The historian Niall Ferguson, a self-declared neo-imperialist, bemoaned that “girls no longer play with dolls” and that feminists have forced Europe into demographic decline. More revealingly, the few women publicly critical of the bellicosity, such as Katha Pollitt, Susan Sontag and Arundhati Roy, were “mounted on poles for public whipping” and flogged, Barbara Kingsolver wrote, with “words like bitch and airhead and moron and silly”. At the same time, Vanity Fair’s photo essay on the Bush administration at war commended the president for his masculine sangfroid and hailed his deputy, Dick Cheney, as “The Rock”.

Psychotic masculinity can be seen everywhere from ISIS to mass-murderer Anders Breivik, who claimed Viking ancestry

Some of this post-9/11 cocksmanship was no doubt provoked by Osama bin Laden’s slurs about American manhood: that the free and the brave had gone “soft” and “weak”. Humiliation in Vietnam similarly brought forth such cartoon visions of masculinity as Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger. It is also true that historically privileged men tend to be profoundly disturbed by perceived competition from women, gay people and diverse ethnic and religious groups. In Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture at the Fin de Siecle (1990) Elaine Showalter described the great terror induced among many men by the very modest gains of feminists in the late 19th century: “fears of regression and degeneration, the longing for strict border controls around the definition of gender, as well as race, class and nationality”.

In the 1950s, historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr was already warning of the “expanding, aggressive force” of women, “seizing new domains like a conquering army”. Exasperated by the “castrated” American male and his “feminine fascination for the downtrodden”, Schlesinger, the original exponent of muscular liberalism, longed for the “frontiersmen” of American history who “were men, and it did not occur to them to think twice about it”.

These majestically male makers of the modern west are being forced to think twice about a lot today. Gay men and women are freer than before to love whom they love, and to marry them. Women expect greater self-fulfilment in the workplace, at home and in bed. Trump may have the biggest nuclear button, but China leads in artificial intelligence as well as old-style mass manufacturing. And technology and automation threaten to render obsolete the men who push and pull things – most damagingly in the west.

Many straight white men feel besieged by “uppity” Chinese and Indian people, by Muslims and feminists, not to mention gay bodybuilders, butch women and trans people. Not surprisingly they are susceptible to Peterson’s notion that the ostensible destruction of “the traditional household division of labour” has led to “chaos”. This fear and insecurity of a male minority has spiralled into a politics of hysteria in the two dominant imperial powers of the modern era. In Britain, the aloof and stiff upper-lipped English gentleman, that epitome of controlled imperial power, has given way to such verbally incontinent Brexiters as Boris Johnson. The rightwing journalist Douglas Murray, among many elegists of English manhood, deplores “emasculated Italians, Europeans and westerners in general” and esteems Trump for “reminding the west of what is great about ourselves”. And, indeed, whether threatening North Korea with nuclear incineration, belittling people with disabilities or groping women, the American president confirms that some winners of modern history will do anything to shore up their sense of entitlement.

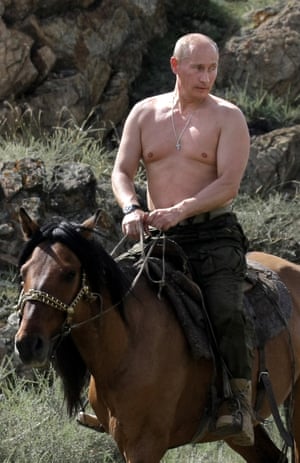

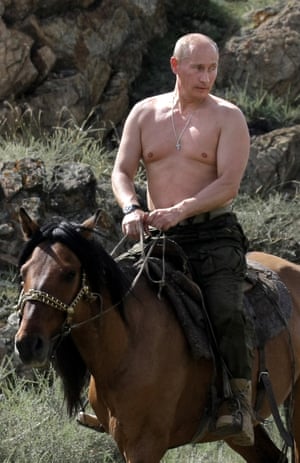

Rear-guard machismo … Vladimir Putin on holiday in southern Siberia in 2009. Photograph: Alexey Druzhinin/AFP/Getty Images

But gaudy displays of brute manliness in the west, and frenzied loathing of what the alt-rightists call “cucks” and “cultural Marxists”, are not merely a reaction to insolent former weaklings. Such manic assertions of hyper-masculinity have recurred in modern history. They have also profoundly shaped politics and culture in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Osama bin Laden believed that Muslims “have been deprived of their manhood” and could recover it by obliterating the phallic symbols of American power. Beheading and raping innocent captives in the name of the caliphate, the black-hooded young volunteers of Islamic State were as obviously a case of psychotic masculinity as the Norwegian mass-murderer Anders Behring Breivik, who claimed Viking warriors as his ancestors. Last month, the Philippines president Rodrigo Duterte told female rebels in his country that “We will not kill you. We will just shoot you in the vagina.” Tormenting hapless minorities, India’s Hindu supremacist chieftains seem obsessed with proving, as one asserted after India’s nuclear tests in 1998, “we are not eunuchs any more”.

Morbid visions of castration and emasculation, civilisational decline and decay, connect Godse and Schlesinger to Bin Laden and Trump, and many other exponents of a rear-guard machismo today. They are susceptible to cliched metaphors of “soft” and “passive” femininity, “hard” and “active” masculinity; they are nostalgic for a time when men did not have to think twice about being men. And whether Hindu chauvinist, radical Islamist or white nationalist, their self-image depends on despising and excluding women. It is as though the fantasy of male strength measures itself most gratifyingly against the fantasy of female weakness. Equating women with impotence and seized by panic about becoming cucks, these rancorously angry men are symptoms of an endemic and seemingly unresolvable crisis of masculinity.

When did this crisis begin? And why does it seem so inescapably global? Writing Age of Anger: A History of the Present, I began to think that a perpetual crisis stalks the modern world. It began in the 19th century, with the most radical shift in human history: the replacement of agrarian and rural societies by a volatile socio-economic order, which, defined by industrial capitalism, came to be rigidly organised through new sexual and racial divisions of labour. And the crisis seems universal today because a web of restrictive gender norms, spun in modernising western Europe and America, has come to cover the remotest corners of the earth as they undergo their own socio-economic revolutions.

There were always many ways of being a man or a woman. Anthropologists and historians of the world’s astonishingly diverse pre-industrial societies have consistently revealed that there is no clear link between biological makeup and behaviour, no connection between masculinity and vigorous men, or femininity and passive women. Indians, British colonialists were disgusted to find, revered belligerent and sexually voracious goddesses, such as Kali; their heroes were flute-playing idlers such as Krishna. A vast Indian literature attests to mutably gendered men and women, elite as well as folk traditions of androgyny and same-sex eroticism.

These unselfconscious traditions began to come under unprecedented assault in the 19th century, when societies constituted by exploitation and exclusion, and stratified along gender and racial lines, emerged as the world’s most powerful; and when such profound shocks of modernity as nation-building, rural-urban migration, imperial expansion and industrialisation drastically changed all modes of human perception. A hierarchy of manly and unmanly human beings had long existed in many societies without being central in them. During the 19th century, it came to be universally imposed, with men and women straitjacketed into specific roles.

‘In the 19th century, the ideal of a strong, fearless manhood came to be embodied in muscular selves, nations, empires and races’

The modern west appears, in the western supremacist version of history, as the guarantor of equality and liberty to all. In actuality, a notion of gender (and racial) inequality, grounded in biological difference, was, as Joan Wallach Scott demonstrates in her recent book Sex and Secularism, nothing less than “the social foundation of modern western nation-states”. Immanuel Kant dismissed women as incapable of practical reason, individual autonomy, objectivity, courage and strength. Napoleon, the child of the French Revolution and the Enlightenment, believed women ought to stay at home and procreate; his Napoleonic Code, which inspired state laws across the world, notoriously subordinated women to their fathers and husbands. Thomas Jefferson, America’s founding father, commended women, “who have the good sense to value domestic happiness above all other” and who are “too wise to wrinkle their foreheads with politics”. Such prejudices helped replace traditional patriarchy with the exclusionary ideals of masculinity as the modern world came into being.

On such grounds, women were denied political participation and forced into subordinate roles in the family and the labour market. Pop psychologists periodically insist that men are from Mars and women from Venus, lamenting the loss of what Peterson calls “traditional” divisions of labour, without acknowledging that capitalist, industrial and expansionist societies required a fresh division of labour, or that the straight white men who supervised them deemed women unfit, due to their physical or intellectual inferiority, to undertake territorial aggrandisement, nation-building, industrial production, international trade, and scientific innovation. Women’s bodies were meant to reproduce and safeguard the future of the family, race and nation; men’s were supposed to labour and fight. To be a “mature” man was to adjust oneself to society and fulfil one’s responsibility as breadwinner, father and soldier. “When men fear work or fear righteous war,” as Theodore Roosevelt put it, “when women fear motherhood, they tremble on the brink of doom.” As the 19th century progressed, many such cultural assumptions about male and female identity morphed into timeless truths. They are, as Peterson’s rowdy fan club reveals, more vigorously upheld today than the “truths” of racial inequality, which were also simultaneously grounded in “nature”, or pseudo-biology.

Scott points out that the modes of sexual difference defined in the modernising west actually helped secure, “the racial superiority of western nations to their ‘others’ – in Africa, Asia, and Latin America”. “White skin was associated with ‘normal’ gender systems, dark skin with immaturity and perversity.” Thus, the British judged their Kali-worshipping Indian subjects to be an unmanly and childish people who ought not to wrinkle their foreheads with ideas of self-rule. The Chinese were widely seen, including in western Chinatowns, as pigtailed cowards. Even Muslims, Christendom’s formidable old rivals, came to be derided as pitiably “feminine” during the high noon of imperialism.

Gandhi explicitly subverted these gendered prejudices of European imperialists (and their Hindu imitators): that femininity was the absence of masculinity. Rejecting the western identification of rulers with male supremacy and subjecthood with feminine submissiveness, he offered an activist politics based on rigorous self-examination and maternal tenderness. This rejection eventually cost him his life. But he could see how much the male will to power was fed by a fantasy of the female other as a regressive being – someone to be subdued and dominated – and how much this pathology had infected modern politics and culture.

As Hindu nationalisation got into gear, formerly chubby Bollywood stars began to flaunt bulging biceps

Its most insidious expression was the conquest and exploitation of people deemed feminine, and, therefore, less than human – a violence that became normalised in the 19th century. For many Europeans and Americans, to be a true man was to be an ardent imperialist and nationalist. Even so clear-sighted a figure as Alexis de Tocqueville longed for his French male compatriots to realise their “warlike” and “virile” nature in crushing Arabs in north Africa, leaving women to deal with the petty concerns of domestic life.

As the century progressed, the quest for virility distilled a widespread response among men psychically battered by such uncontrollable and emasculating phenomena as industrialisation, urbanisation and mechanisation. The ideal of a strong, fearless manhood came to be embodied in muscular selves, nations, empires and races. Living up to this daunting ideal required eradicating all traces of feminine timidity and childishness. Failure incited self-loathing – and a craving for regenerative violence. Mocked with such unmanly epithets as “weakling” and “Oscar Wilde”, Roosevelt tried to overcome, Gore Vidal once pointed out, “his physical fragility through ‘manly’ activities of which the most exciting and ennobling was war”. It is no coincidence that the loathing of homosexuals, and the hunt for sacrificial victims such as Wilde, was never more vicious and organized than during this most intense phase of European imperialism.

One image came to be central to all attempts to recuperate the lost manhood of self and nation: the invincible body, represented in our own age of extremes by steroid-juiced, knobbly musculature. Actually, size matters today much less than it ever did; not many muscles are required for increasingly sedentary work habits and lifestyles. Nevertheless, an obsession with raw brawn and sheer mass still shapes political cultures. Trump’s boasts about the size of his body parts were preceded by Vladimir Putin’s displays of his pectorals – advertisements for a Russia re-masculinised after its emasculation by Boris Yeltsin, a flabby drunk. But shirtless hunks are also a striking recent phenomenon in Godse’s “rising” India. In the 90s, just as India’s Hindu nationalisation got into gear, formerly scrawny or chubby Bollywood stars began to flaunt glisteningly hard abs and bulging biceps; Rama, the lean-limbed hero of the Ramayana, started to resemble Rambo in calendar art and political posters. These buffed-up bodies of popular culture foreshadowed Modi, who rose to power boasting of his 56-inch chest, and promising true national potency to young unemployed stragglers.

This vengeful masculinist nationalism was the original creation of Germans in the early 19th century, who first outlined a vision of creating a superbly fit people or master race and fervently embraced such typically modern forms of physical exercise as gymnastics, callisthenics and yoga and fads like nudism. But pumped-up anatomy emerged as a “natural” embodiment of the evidently exclusive male virtue of strength only as the century ended. As societies across the west became more industrial, urban and bureaucratic, property-owning farmers and self-employed artisans rapidly turned into faceless office workers and professionals. With “rational calculation” installed as the new deity, “each man”, Max Weber warned in 1909, “becomes a little cog in the machine”, pathetically obsessed with becoming “a bigger cog”. Increasingly deprived of their old skills and autonomy in the iron cage of modernity, working class men tried to secure their dignity by embodying it in bulky brawn.

India’s prime minister Narendra Modi rose to power boasting of his 56-inch chest, and promising true national potency. Photograph: Danish Ismail/Reuters

Historians have emphasised how male workers, humiliated by such repressive industrial practices as automation and time management, also began to assert their manhood by swearing, drinking and sexually harassing the few women in the workforce – the beginning of an aggressive hardhat culture that has reached deep into blue-collar workplaces during the decades-long reign of neoliberalism. Towards the end of the 19th century large numbers of men embraced sports and physical fitness, and launched fan clubs of pugnacious footballers and boxers.

It wasn’t just working men. Upper-class parents in America and Britain had begun to send their sons to boarding schools in the hope that their bodies and moral characters would be suitably toughened up in the absence of corrupting feminine influences. Competitive sports, which were first organised in the second half of the 19th century, became a much-favoured means of pre-empting sissiness – and of mass-producing virile imperialists. It was widely believed that putative empire-builders would be too exhausted by their exertions on the playing fields of Eton and Harrow to masturbate.

But masculinity, a dream of power, tends to get more elusive the more intensely it is pursued; and the dread of emasculation by opaque economic, political and social forces continued to deepen. It drove many fin de siècle writers as well as politicians in Europe and the US into hyper-masculine trances of racial nationalism – and, eventually, the calamity of the first world war. Nations and races as well as individuals were conceptualised as biological entities, which could be honed into unassailable organisms. Fear of “race suicide”, cults of physical education and daydreams of a “New Man” went global, along with strictures against masturbation, as the inflexible modern ideology of gender difference reached non-western societies.

European colonialists went on to impose laws that enshrined their virulent homophobia and promoted heterosexual conjugality and patrilineal orders. Their prejudices were also entrenched outside the west by the victims of what the Indian critic Ashis Nandy calls “internal colonialism”: those subjects of European empires who pleaded guilty to the accusation that they were effeminate, and who decided to man up in order to catch up with their white overlords.

This accounts for a startling and still little explored phenomenon: how men within all major religious communities – Buddhist, Hindu and Jewish as well as Christian and Islamic – started in the late 19th century to simultaneously bemoan their lost virility and urge the creation of hard, inviolable bodies, whether of individual men, the nation or the umma. These included early Zionists (Max Nordau, who dreamed of Muskeljudentum, “Jewry of Muscle”), Asian anti-imperialists (Swami Vivekananda, Modi’s hero, who exhorted Hindus to build “biceps”, and Anagarika Dharmapala, who helped develop the muscular Buddhism being horribly flexed by Myanmar’s ethnic-cleansers these days) as well as fanatical imperialists such as Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Scout movement.

The most lethal consequences of this mimic machismo unfolded in the first decades of the 20th century. “Never before and never afterwards”, as historian George Mosse, the pioneering historian of masculinity, wrote, “has masculinity been elevated to such heights as during fascism”. Mussolini, like Roosevelt, transformed himself from a sissy into a fire-breathing imperialist. “The weak must be hammered away,” declared Hitler, another physically ill-favoured fascist. Such wannabe members of the Aryan master race accordingly defined themselves against the cowardly Jew and discovered themselves as men of steel in acts of mass murder.

This hunt for manliness continues to contaminate politics and culture across the world in the 21st century. Rapid economic, social and technological change in our own time has plunged an exponentially larger number of uprooted and bewildered men into a doomed quest for masculine certainties. The scope for old-style imperialist aggrandisement and forging a master race may have diminished. But there are, in the age of neoliberal individualism, infinitely more unrealised claims to masculine identity in grotesquely unequal societies around the world. Myths of the self-made man have forced men everywhere into a relentless and often futile hunt for individual power and wealth, in which they imagine women and members of minorities as competitors. Many more men try to degrade and exclude women in their attempt to show some mastery that is supposed to inhere in their biological nature.

Fear of feminizsation has driven demagogic movements like that unleashed by the locker room bully in the White House

Frustration and fear of feminisation have helped boost demagogic movements similar to the one unleashed by the locker room bully in the White House. Godse’s hyper-masculine cliches have vanquished the traditions of androgyny that Gandhi upheld – and not just in India. Young Pakistani men revere the playboy-turned-politician Imran Khan as their alpha male redeemer; they turn viciously on critics of his indiscretions. Similarly embodying a triumphant masculinity in the eyes of his followers, the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan can do no wrong. Rodrigo Duterte jokes, with brazen frequency, about rape.

Misogyny now flourishes in the public sphere because, as in modernising Europe and America, many toilers daydream of a primordial past when real men were on top, and women knew their place. Loathing of “liberated” women who seem to be usurping male domains is evident not only on social media but also in brutal physical assaults. These are sanctioned by pseudo-traditional ideologies such as Hindu supremacism and Islamic fundamentalism that offer to many thwarted men in Asia and Africa a redeeming machismo: the gratifying replacement of neoliberalism’s bogus promise of equal opportunity with old-style patriarchy.

Susan Faludi argues that many Americans used the 9/11 attacks to shrink the gains of feminism and push women back into passive roles. Peterson’s traditionalism is the latest of many attempts in the west in recent years to restore the authority of men, or to remasculinise society. These include the deployment of “shock-and-awe” violence, loathing of cucks, cultural Marxists and feminists, re-imagining a silver-spooned posturer like Bush as superman, and, finally, the political apotheosis of a serial groper.