Samira Shackle in The Guardian

January 2004. The mobile phone footage is grainy, the sounds of a riot audible in the background. A group of British soldiers grab four Iraqi boys on the street and drag them into their barracks. The camera zooms in and out as the soldiers beat them. A soldier walks up to one boy and kicks him between the legs. Another punches a boy in the head and stomach. The soldier filming keeps up a steady patter. “Oh yes! You’re going to get it,” he says. He imitates their screams for mercy. “Oh please! Please no!” Other soldiers pass in and out of shot, apparently indifferent.

This footage, from southern Iraq, would be passed to the News of the World and published two years later. It was one of the first cases of British soldiers abusing Iraqi civilians to become public, and provoked fury both in Iraq and Britain. “Jail them,” demanded a Daily Star article. Across the Middle East, the footage looped on news channels. In the southern Iraqi city of Basra, where British troops were stationed, 1,000 people took to the streets in protest, chanting “No, no, Tony Blair” and burning British flags outside the consulate.

The nine soldiers involved – eight carrying out the beating, one filming the attack – were questioned. But almost a year later, the Service Prosecuting Authority (SPA), the military equivalent of the Crown Prosecution Service, decided not to bring charges. Although there was sufficient evidence to prosecute two of the soldiers, the statute of limitations had expired and it was deemed not in the public interest to pursue them.

This was not the only case of alleged abuse by British soldiers in Iraq. Over time, a steady drip of shocking allegations about British troops emerged in the press. One of the most notorious was at Camp Breadbasket, an aid distribution centre in Basra, where a group of soldiers beat and humiliated Iraqi prisoners, taking photographs of the abuse. As stories of torture and unlawful killings in British custody came out, they fed into the wider sense of outrage about the war. The public wanted answers about how politicians had sold the war to them in the first place, how the media had failed to scrutinise politicians’ claims in the run-up to the war, how the military had failed to prepare and equip its troops. The shocking stories of abuse and torture by British troops added to the fury.

But over the past three years, the question of whether British soldiers committed crimes in Iraq, and the scale on which it happened, has been largely displaced by outrage over attempts to investigate them. In the media, rhetoric has shifted radically – from horror at the alleged crimes of British soldiers, to outrage against human rights lawyers pursuing such allegations. “Mr Cameron MUST stop these vile witch-hunts against our brave troops,” read a 2016 column in the Daily Mail. Conservative politicians have echoed this line. David Cameron, then prime minister, promised to stop “spurious” claims. Defence secretary Michael Fallon criticised “unscrupulous” lawyers; armed forces minister Penny Mordaunt described these lawyers’ actions as the “enemy of justice”. When Cameron left office, his successor, Theresa May, lambasted “activist, leftwing human rights lawyers”.

The target of most of these complaints from cabinet ministers has been an investigation launched by the UK government itself. The Iraq Historic Allegations Team (Ihat) was set up by the Labour government in 2010, to draw a line under lingering allegations from an unpopular war and dispatch the idea that military misconduct was widespread. It aimed to investigate credible claims of abuses in Iraq and secure criminal prosecutions where appropriate. But if Ihat was supposed to be a way to decisively establish guilt or innocence, it failed spectacularly.

By February 2017, the investigation had become the centre of a national scandal over its methods and scope, and the government announced it would shut Ihat down. “What was meant to be an administrative exercise, tidying up a few loose ends, had taken off into the stratosphere,” Nick Harvey, minister for the armed forces from 2010-12, told me. A parliamentary inquiry concluded Ihat had “directly harmed the defence of our nation” by making soldiers on the battlefield anxious about later legal repercussions. When Ihat closed, outstanding cases were reduced, overnight, from 3,400 to just 20. It had cost the taxpayer £34m and failed to secure a single prosecution.

The collapse of Ihat seems likely to mark the end of serious attempts to investigate alleged crimes by British soldiers in Iraq, leaving questions about the scale of abuses and accountability unanswered. After such a public failure, what politician would want to reopen the issue? Yet, behind the headlines of corrupt lawyers and incompetent investigators, the true story of Ihat is more complicated. Both military advocates and human rights defenders agree that the scandal around Ihat was at the very least, politically convenient for the Ministry of Defence. With human rights lawyers cast as the villains, the MoD could avoid uncomfortable questions about its own role in training soldiers in procedures that breached the Geneva conventions. “At times, the MoD has been tempted to throw the uniform under the bus,” says Johnny Mercer, a Conservative MP who was instrumental in Ihat’s closure.

Fifteen years after it began, we are no closer to holding any politicians or high-ranking soldiers accountable for the disaster of the Iraq war. The further we get from the events, the more elusive proper examination has become. Rather than time giving a measure of distance, the tenor of the debate has degenerated to a point where the very words “human rights lawyer” are used as an insult by top politicians. Meanwhile, anger at the government’s own investigation into alleged abuses by British soldiers in Iraq has fuelled scepticism about civilians’ right to even question the actions of the armed forces overseas.

When British combat operations in Iraq ended in 2009, Saddam Hussein had been ousted, but terrorism and sectarian war were surging. More than 100,000 Iraqis had been killed, as well as 4,371 Americans and 179 British soldiers. “Daily life was a mess,” says Safaa Khalaf, a journalist from Basra who covered the British occupation. “The British were saying the city was safe, but armed groups controlled residential areas. Services had been completely destroyed and there were no efforts to rebuild.”

British involvement had cost £9.6bn and the war was grossly unpopular at home. A ComRes poll at the time found that 37% of the British public believed that Blair should be tried as a war criminal. Gordon Brown, keen to differentiate his premiership, established the Chilcot inquiry to help the UK to “learn the lessons” of the Iraq war. In the same month that combat operations ended, a public inquiry was also launched into the killing of Baha Mousa, a 26-year-old hotel receptionist beaten to death in Basra by British soldiers in 2003. (The inquiry would later conclude that these soldiers subjected Iraqi detainees, including Mousa, to “serious, gratuitous violence”.) Another public inquiry into claims that British soldiers murdered and mutilated nine Iraqi detainees, known as the al-Sweady inquiry, launched the same year.

A crowd burn a British flag to protest the 2003 killing of 26-year-old Baha Mousa. Photograph: AP

The families of Iraqi victims in both inquiries were represented by the same lawyer: Phil Shiner, founder of Public Interest Lawyers, a small Birmingham-based practice. Within government, Shiner was hated – “We had the strong feeling that he was a bad apple,” one former Labour minister told me – but many of his fellow lawyers admired his determination to hold power to account. In 2004, Shiner had been named human rights lawyer of the year by the campaign group Liberty, and in 2007, the Law Society named him solicitor of the year.

In February 2010, Shiner began court proceedings to seek investigation into further claims of ill-treatment of Iraqis. “We were at risk of having a public inquiry for every allegation [of abuse in Iraq],” says Bill Rammell, who was minister for the armed forces during that period. “That would take years – and in the intervening period, the whole reputation of the armed forces would be besmirched.”

To draw a line under the continued legal challenges, MoD officials proposed the creation of Ihat, a legal body that would investigate allegations of crimes, and where appropriate, pursue prosecutions of individual soldiers. Having been signed off by Brown, it was announced publicly in March 2010. “Ihat was a concerted attempt to pull all the allegations together, throw resources at them and process them as quickly as possible,” said Rammell.

One of the central questions raised by Ihat is who, ultimately, is responsible for crimes committed by British personnel in war? Individual service personnel bear criminal responsibility for crimes they commit in war, such as murdering civilians or torturing prisoners. Under international criminal law, senior officers can also be held accountable for the actions of their subordinates if they did not take “necessary and reasonable” action to prevent it. Under the act that Britain signed when it joined the international criminal court (ICC) in 2001, generals and even politicians are potentially liable for systematic abuses by British soldiers. This has proved largely theoretical, however: the last person in Britain to be prosecuted for crimes committed by forces under their command was in 1651 during the civil war.

In Iraq, this question of command responsibility was particularly important. Numerous public inquiries have concluded that five banned interrogation techniques were widely used by British soldiers. These techniques – hooding, white noise, sleep deprivation, food deprivation and stress positions – were outlawed by the UK in 1972 and breach the Geneva conventions. But by the time of the Iraq war, training manuals did not mention that these techniques were forbidden. Nor did the manuals formally advocate using these techniques – they simply were not mentioned at all. Institutional knowledge of the ban seemingly having been lost, in the chaos of the war – where thousands of Iraqi men and boys were arrested without adequate holding facilities – soldiers may have been told by commanding officers to, for instance, hood detainees. This meant that, under Ihat, soldiers could theoretically face criminal prosecution for things they were told by their commanders to do.

Crucially, Ihat was set up in such a way that it could not address wider questions of accountability. Rather than considering systemic problems, it was limited to prosecuting individual soldiers. Overseen by civil servants employed by the MoD, Ihat had a main staff consisting of around 150 investigators who would look into allegations in the same way that civilian police might. If an investigation gathered sufficient evidence, the case would be passed on to the SPA, which would then decide whether to proceed. The odd structure of the organisation – not quite a public inquiry, not quite a police investigation – is a sign of how unusual it was; there are no comparable examples of a country domestically investigating allegations of crimes committed in an overseas war.

By the time Ihat got going in November 2010, the Labour government had been replaced by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition. Government insiders told me that David Cameron was reluctant to proceed, and would have preferred to shut down the whole process. But he had little choice. In 2011, the European court of human rights ruled that the UK had a duty to investigate allegations of deaths and ill treatment involving its service personnel in Iraq. If it didn’t, Britain and the politicians and generals in power at the time of the Iraq war might have a case to answer in the ICC.

The view within government under Labour, when Ihat was set up, was that it would show Britain was taking responsibility by punishing the worst cases of abuse, while simultaneously proving that there were relatively few serious incidents. Despite Cameron’s reluctance, the coalition had a broadly similar attitude. “What was not anticipated at the outset was the sheer scale of what Ihat was going to end up looking at,” said Nick Harvey, the Liberal Democrat who replaced Rammell as minister for the armed forces.

On launching Ihat in 2010, Harvey predicted that it would conclude its work within two years. In fact, it barely even started until 2012, as Shiner repeatedly took the government to court to dispute its structure and independence. (“He could start an argument in a phone box by himself,” said one acquaintance.) Initially, Ihat’s investigative team were mostly drawn from a branch of the British military police that had been active in Iraq during the occupation. Shiner successfully argued in court that they had a conflict of interest, and in 2012, Ihat was restructured and restaffed with civilians – mostly retired police detectives. The new aim was completion in 2019, with a budget forecast of £57m.

For the first few years of its operation, few people paid much attention to the work Ihat was doing. In 2013, Shiner’s daughter Bethany, a recent law school graduate, started working at Public Interest Lawyers’ Birmingham office. It was a small firm, employing around seven solicitors, and Shiner was the only partner. Public Interest Lawyers took the lead in gathering cases from Iraqis, ultimately bringing 65% of Ihat’s cases, although another firm, Leigh Day, was also involved. Public Interest Lawyers was paid a set fee for gathering statements on a case-by-case basis by the Legal Aid Agency.

Bethany Shiner, who is now 30, was immediately thrust into the Iraq litigation. She and other junior lawyers took statements from Iraqis over the phone, with the help of an interpreter. Many of them were based in Basra, although calls came from around the country. “The allegations ranged from beatings, hoodings, poor detention conditions, all the way to sexual assault,” Bethany said. “You’d hear the same details again and again.” Some of the firm’s lawyers were traumatised by repeatedly hearing stories of sexual assault and torture.

A youth hurls a rock at British soldiers during a violent protest in Basra in 2004. Photograph: Reuters

Most of the cases came to Public Interest Lawyers via a UK-based translation and logistics company run by a British Iraqi, which employed a fixer in Basra, Abu Jamal, to liaise with Iraqi claimants and witnesses. Abu Jamal was a prominent local figure who was well trusted in Basra, and connected Iraqis to the lawyers. In addition to working for Public Interest Lawyers, for three years Abu Jamal was hired directly by Ihat for a salary of £40,000 per year, to find witnesses, help them get visas, and sometimes accompany them overseas for interviews with Ihat staff. “Without him nothing would have happened,” one former investigator told me.

It is testament to the internal chaos of Ihat that no one appears to have stopped to question whether it was appropriate for someone to be employed by both lawyers bringing the claims and the investigators scrutinising them. Although Public Interest Lawyers maintain that Abu Jamal was simply liaising, some journalists later alleged that he had directly approached clients to solicit for business. This practice – often dismissed as “ambulance-chasing” – is permitted in some countries, but is strictly forbidden in the UK. If claimants were coming to Abu Jamal – as he and Public Interest Lawyers have maintained – then that was permissible. If he was cold-calling them, as alleged, it would not. It has never been proven that Abu Jamal was paid to directly solicit clients for Ihat.

Whatever was happening behind the scenes, hundreds of Iraqis were coming forward with stories of abuse at the hands of British soldiers. As the number of claims grew, a sense of purpose united staff at Public Interest Lawyers. “We were trying to find out what happened,” said Bethany. “It was about finding the truth and holding those responsible accountable.” This was no easy task. Because it was pursuing criminal prosecutions, Ihat’s cases had to meet the standard of criminal proof: it had to be beyond reasonable doubt that the alleged incidents took place. Yet most of the alleged crimes had taken place a decade earlier, in an active war zone, so crime scenes were never secured and vital evidence had not been gathered. Alleged victims and witnesses were thousands of miles away, in a still war-torn country. Ihat judged it unsafe for investigators to go to Iraq, so arrangements were made for Iraqi victims and witnesses to be interviewed in Turkey. From 2013, when investigations got underway in earnest, until 2016, these trips happened almost monthly.

As Public Interest Lawyers gathered cases, they passed them on to Ihat for consideration. Usually, this would consist of a written statement, accompanied by supporting documents, such as evidence of detention, medical records or photographs of injuries. The lawyers would ensure the basic facts checked out and that claims were credible, and pass the cases on to a team of civil servants, who decided which claims merited further investigation. As the number of allegations mushroomed, there appears to have been little direction from above about which cases were worth pursuing. “There wasn’t much of a triage system to focus attention on the most serious allegations or those most likely to result in prosecution,” one insider told me.

Of the hundreds of cases Ihat investigated, not one ended in prosecution. While this has been held up in the rightwing press and in government as evidence that the claims were “spurious” and the investigation incompetent, those involved feel that the structure of Ihat was the stumbling block. “My overall feeling is that there was a lot of evidence of criminal wrongdoing, and that nobody has been held to account,” said Jonathan (not his real name), who was part of an Ihat team that went on numerous trips to Turkey. Usually, these trips would last about a week, with five or six Iraqi witnesses interviewed by Ihat investigators. Legal representatives from Public Interest Lawyers would also be there. “Of course there were some false claims, but most of the people I saw I believed to be genuine,” said Jonathan. He emphasised that many interviews were with witnesses who had no financial motive as they were not eligible for compensation.

Many working at the ground level – from the lawyers representing Iraqis to the Ihat investigators – felt that they were being asked to pursue the wrong target, investigating individuals rather than looking at systemic problems in the military. But they were trapped within the process. “Of course, individual soldiers had personal responsibility – but allegations often related to the way in which personnel had been trained, what they were told to do, how they were told to treat people,” said Bethany. “It was about the government and the MoD in particular.”

Paul (not his real name), a retired police detective who worked as an investigator, felt frustrated that his inquiries were limited to low-ranking individuals. Some of the British soldiers he interviewed were functionally illiterate, he said: “They’d signed statements taken immediately after the event [for which they were being investigated]. But I found they could barely read or write, and they’d just signed anything so they could go home,” said Paul. Wanting to investigate the chain of command, in one case, he requested permission from Ihat’s leadership to interview a senior army officer in relation to an alleged unlawful killing. This was refused. Every time he tried to pursue this line of inquiry, he claims that it was shut down by Ihat’s leadership or MoD lawyers.

According to Jonathan, many of his colleagues felt increasingly frustrated. “Many complained that they had gathered what they thought was enough evidence to prosecute, and then they’d have an MoD lawyer go to the senior leadership of Ihat and tell them to drop the case.” An MoD spokesperson denied these claims, saying that “Officers of very senior ranks were interviewed in many Ihat investigations when the evidence and line of inquiry required it, and no investigation was shut down prematurely.” Paul says: “I don’t think anyone there was bright enough for it to be a conspiracy, but I felt the MoD were putting pressure on the senior leadership to wrap things up.”

Paul describes meeting the family of an Iraqi who had allegedly died in British custody. They asked how they could trust him when he was employed by the British government. “I will never forget that I looked that man in the eye,” said Paul. “I made a promise to do a fair investigation that I wasn’t able to keep.”

At the end of 2014, Maj Robert Campbell was on leave and about to go on holiday when he received a call from an ex-girlfriend, who told him Ihat investigators had been asking about him. It was the first indication Campbell had that he was under investigation for murder. The inquiries related to a 2003 incident where a 19-year-old Iraqi, Said Shabram, had drowned in Basra. At the time, to control crowds and prevent looting, British troops would sometimes force civilians into the Shatt al-Arab river that runs through the city, a practice known as “wetting”. The allegation was that Campbell and two other soldiers had forced Shabram into the water, which they denied. Campbell and two of his soldiers had been investigated and cleared on four separate occasions by the military authorities. Ihat’s involvement marked the fifth investigation, although it was the first by civilians.

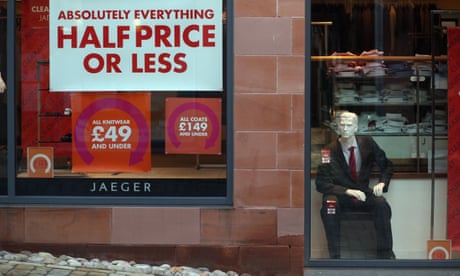

Front cover of the News of the World from Sunday 12 February 2006. Photograph: PA

After Campbell had spoken to his ex-girlfriend, he immediately called his commanding officer. “They said ‘There’s nothing we can do, don’t worry about it’,” Campbell told me. He suffers from PTSD, and his mental health deteriorated as allegations that he had thought were settled suddenly resurfaced. In the months that followed, he received no clear information on how the investigation was progressing – a charge echoed by other soldiers investigated by Ihat, many of whom spent months or years under a cloud of uncertainty. Nor was Campbell offered support by the army or the MoD – there was no clear advice about what to do, and no financial support was provided to cover the cost of hiring a lawyer. He and the other soldiers accused felt ostracised. “We were guilty until proven innocent,” he said.

One of Ihat’s principles, set out by the MoD when it was launched, was that witnesses would always be given advance warning before being approached in person, and that suspects would be informed first by their chain of command. But the MoD later admitted that over 300 potential witnesses, as well as seven suspects, were contacted without prior warning. It would later emerge that some Ihat investigators had used troubling techniques such as telling soldiers not to mention the allegations to anyone, or asking them to meet in car parks. One Ihat investigator was later convicted of impersonating a police officer after using an old warrant card to demand entry to army barracks.

Campbell’s anxiety turned to anger when he found out that the army had disclosed his service records to Ihat without his consent and without informing him. “The army sold us out,” he said. “Forget the MoD. The army handed over my service records and kept me in the dark about what was going on with the investigations. So who is looking out for us?” While unaware of the murder investigation against him, Campbell was deployed to Afghanistan in 2011, where he was severely injured. He is now permanently disabled, with damaged hearing, and walks with a cane. “I would have made different decisions had I known I was under investigation for murder. I might not have continued fighting and fucking dying for these wankers,” he said. “I’m finished now. I’m broken.”

For years, the day-to-day problems with Ihat attracted little media attention. But as the verdict in another inquiry into alleged crimes in Iraq became a national scandal, the controversy engulfed Ihat. On 17 December 2014, the judgment in what was known as the al-Sweady inquiry came out. A group of Iraqi complainants, represented by Public Interest Lawyers and Leigh Day, had alleged that British forces had committed serious battlefield crimes during hand-to-hand combat in a 2004 clash called the Battle of Danny Boy, culminating with the murder and mutilation of nine detainees. The judge found that nine detainees had indeed been mistreated – but that the most serious allegations, of torture and murder, were “wholly without foundation and entirely the product of deliberate lies, reckless speculation and ingrained hostility”.

The al-Sweady inquiry was not part of Ihat, but both Leigh Day and Public Interest Lawyers had worked on the case and both received furious criticism. On the same day the inquiry released its report, Michael Fallon, then defence secretary, gave a statement to the Commons, calling for measures to stop “unscrupulous” lawyers receiving public money for lengthy inquiries. (The inquiry cost around £31m.) Fallon said that the al-Sweady claims were a “shameful attempt to use our legal system to attack and falsely impugn our armed forces”. This was a remarkable attack. Ihat, a state-funded criminal investigation, was ongoing, and the defence minister was criticising the lawyers involved. At Fallon’s request, the two firms were referred to the Solicitors Regulation Authority, a professional body, for misconduct.

Although the al-Sweady case was separate to Ihat, in retrospect it is clear that the judgment marked the beginning of the end for Ihat – and helped transform the public conversation about British military conduct in Iraq. The day after Fallon’s speech, the tabloids went to town (“Shame of the lawyers”, said the Daily Mail’s headline). Staff at Public Interest Lawyers received death threats by email and over the phone. The more serious threats were reported to police. The firm installed a security gate and CCTV. “We felt as if we were under siege,” Bethany Shiner said.

By 2015, Ihat had outlasted yet another government. Among the new MPs elected in May was Johnny Mercer, a former army officer who had served in Afghanistan. Mercer is a young, dynamic man who feels strongly about the poor treatment of veterans. “We treat them like shit,” he told me when we met late last year.

One of Mercer’s highest priorities upon entering parliament as the new MP for Plymouth Moor View was to fight back against Ihat. “It just struck me as a profoundly wrong process,” Mercer said. “I don’t know a single person who served who doesn’t think that those who committed offences should be held to account. But what this struck me as was the denigration of almost the entire British army on baseless evidence.” (Mercer endorses existing measures, such as internal army investigations and courts martial, as a means to hold soldiers to account.)

An image of Iraqi detainees guarded by a British soldier shown at the al-Sweady inquiry. Photograph: PA

When it comes to the scale of British wrongdoing in Iraq, many human rights advocates point to the £21.8m paid out by the MoD to Iraqi claimants in over 300 cases, citing it as a tacit admission of guilt. Mercer disagrees. “To settle without even speaking to the soldiers, you’re assuming their guilt before any sort of due process or investigation has taken place,” he said. “I certainly got the impression in Whitehall that somehow soldiers are ‘bad’. They were looking at two accounts, and always siding with the Iraqi civilian or with Shiner. I just don’t believe that that many of our servicemen and women were liars.”

Mercer began asking questions within parliament about the slow progress of Ihat and the behaviour of investigators. He was shocked to find that “ministers didn’t really know what was going on”, denying that Ihat investigators had knocked on doors of soldiers without writing to them in advance. Mercer felt colleagues didn’t appreciate his probing on this issue, particularly given his low place in the “pecking order” of parliamentary politics. But at least in public, his Conservative colleagues seemed to side with him. Penny Mordaunt, then armed forces minister, accused lawyers of “churning out spurious claims against our armed forces”.

Ever since the al-Sweady judgment there had been an intermittent drip of negative coverage about Ihat, which increased as politicians such as Mordaunt, Fallon, Cameron and May criticised the process. In early 2016, the backlash began in earnest, after an article in the Independent stated that prosecutions of soldiers were on the horizon. Disturbing testimonies from soldiers and veterans hit the press, as they described how old allegations had been revived by Ihat, sometimes triggering relapses of PTSD.

Amid these individual tales of human suffering, a clear narrative coalesced: crooked human rights lawyers were persecuting “our brave boys”. Some newspapers even appeared to suggest that civilians had no right at all to question what the military does in the fog of war. “What other country would pay lawyers to persecute its own war heroes?” asked one Daily Mail headline. “Craven politicians and shyster lawyers are not fit to clean our soldiers’ boots,” proclaimed the Sunday Express.

In the run-up to the September 2016 Conservative party conference, Fallon vowed to end Ihat, along with other historic allegations inquiries into Northern Ireland and Afghanistan. The perceived failure of the investigation into abuses in Iraq had become a way to discredit the entire idea of looking seriously at historic abuses committed by British troops. In her keynote speech to conference, the new prime minister Theresa May pledged: “We will never again – in any future conflict – let those activist, leftwing human rights lawyers harangue and harass the bravest of the brave.”

In February 2017, after Mercer’s parliamentary inquiry had interviewed Ihat’s top leaders, he published a report. It described Ihat as an “unmitigated failure” that had “negatively affected the way this country conducts military operations and defends itself”. The day the report came out, Fallon announced Ihat’s closure: a direct response to its findings. Mercer describes it as the best day of his career.

Meanwhile, the Solicitors Regulatory Authority was pressing ahead with its investigation of Public Interest Lawyers and Leigh Day over professional misconduct in the al-Sweady inquiry. Legally, a lawyer isn’t culpable if their client has lied – so although the central claims in the al-Sweady case were untrue, that was not the basis of the misconduct allegations. Instead, they mainly related to a complex web of financial arrangements between the two law firms and a network of Iraqi caseworkers. Leigh Day defended itself at a cost of £7.8m. In September 2017, its lawyers were exonerated of all charges of misconduct. (This verdict is being appealed.)

Public Interest Lawyers could not draw upon the same kind of funds to defend itself, and shut down while the tribunal was going on. Ultimately, the Solicitors Regulatory Authority upheld 22 charges of misconduct against Phil Shiner, who did not attend the tribunal or appoint representation. Most of the charges related to improper fee-sharing arrangements but the authority also found that Shiner had “failed to take proper steps to ensure that the relevant al-Sweady clients complied with their duty of candour to the Court.” It announced he was to be struck off and charged the full costs of the prosecution, with an interim payment of £250,000 due. He declared bankruptcy soon after. (Gavin Williamson, Fallon’s replacement as defence secretary, said prison was “too good” for Shiner.)

Yet despite Shiner’s misconduct in the al-Sweady inquiry, this does not mean that every claim submitted to Ihat was erroneous. In many cases, hard evidence exists – videos of interrogations, medical records, or other documents. “What the government has done is taken the findings against Phil and applied it to all the claimants,” said Bethany. In Iraq, when claimants were informed their cases had been closed, they had no opportunity to challenge it. “They’re frustrated and feel completely out on a limb,” said Bethany. “The one rope that was out there to try and deliver something for them has been cut.”

As politicians rode the wave of outrage over Ihat’s treatment of soldiers, bigger questions about culpability were brushed aside. The aspects of the parliamentary report that criticised Ihat and Shiner were widely reported. Less well remarked was a paragraph towards the end: “It is not disputed that there were incidents of abuse by British armed forces service personnel. However, it appears that this may have been at least partly because the training given to military interrogators was inaccurate and may have placed them, unwittingly, at risk of breaking Geneva conventions in their work”.

When Ihat was closed, all but 20 of the 3,400 investigations into cases of alleged abuse were suddenly shelved, with little explanation. “I don’t think the British army has been held accountable for its actions in Basra,” says Khalaf, the Iraqi journalist. “It’s all been vague and incomprehensible. The Iraqi courts have no authority over the British, while reaching British courts presents obstacles like language, visas and people’s ignorance. Ihat followed up some cases but failed to achieve justice.”

The remaining cases were passed to a new body, the Service Police Legacy Investigations. “I feel like I’ve wasted four years of my life,” said Jonathan, the Ihat employee. Paul, the investigator, felt the same. “When I started, I feared the worst and hoped for the best,” he said. “My wife said: ‘They won’t let you succeed.’ And she was right. I think, without a doubt, the MoD are happy.”

Lawyer Phil Shiner. Photograph: Reuters

Ministers in successive governments had hoped Ihat would finally put to bed the idea that British troops committed widespread abuses against civilians in Iraq. When it closed, it had certainly ended the discussion – but not with a definitive answer on the scale of abuses. Rather, the tone of public discourse had become so partisan that any who questioned the actions of British troops were cast as unpatriotic traitors, while the armed forces were valorised by the very same institution that had, in the words of Johnny Mercer, been tempted to throw them “under a bus”. Everyone involved – whether as an advocate for service personnel or for Iraqi civilians – agrees that the MoD takes great care to protect its own interests, sometimes to the detriment of those serving on the ground. “We’re just political fodder,” Maj Campbell told me. “I think Ihat was possibly set up to cover up the MoD’s lack of training and infrastructure – to cover up their mistakes,” said his lawyer Hilary Meredith. (An MoD spokesperson said: “Ihat investigations were subject to the highest level of scrutiny, including regular and detailed progress hearings in the high court and an independent review. Sir David Calvert-Smith, former director of public prosecutions, found no major flaws with the investigating process.”)

In January 2014, long before his public downfall, Shiner referred Britain to the international criminal court, submitting a dossier of evidence of alleged atrocities in Iraq. This suggests that he, too, was doubtful about the Ihat process. The court only investigates when the state in question is unable or unwilling to examine war crimes domestically. When Shiner filed the motion, he said that it was about “individual culpability” for top leadership. In 2014, the court opened a preliminary investigation, and published initial findings in 2017. All the evidence presented to the ICC had been gathered by Shiner and Public Interest Lawyers, and much of this initial inquiry involved assessing whether the evidence was reliable despite Shiner being discredited. The ICC judged that it was, stating there was evidence of sufficiently widespread wrongdoing – mostly relating to treatment in detention – to merit investigation. The report noted fears of “political interference” in the closure of Ihat.

The ICC looks at the decision-makers: the generals and senior politicians and officials, not at low-ranking soldiers. When Campbell complained about the Ihat investigation to his commanding officers, he was told the process was vital to avoid scrutiny by the ICC. “Why would I care about that?” Campbell asked me. “If Britain goes to the ICC, it’ll be Tony Blair in the dock, not Tommy Atkins from wherever.” He says he would welcome an ICC investigation. He was recently told that he had been referred to Iraq Fatality Investigations, a body with no powers of criminal prosecution, for yet another investigation of his case.

The ICC is now progressing to the next stage, when the court will consider the state’s ability to investigate war crimes fairly itself. Experts suggest that the furore over Ihat might harm Britain’s case. “Clearly, it’s going to be an issue for the ICC,” says Thomas Hansen, a lecturer in law at Ulster University who is researching British accountability for Iraq.

On a cold day in December, I met Bethany Shiner at Middlesex University, where she now lectures in law. That morning, the high court had returned a judgment on two civil cases involving four Iraqis alleging mistreatment in British detention. The judge found them to be “credible” and ruled that soldiers had breached the Geneva conventions. The Iraqis were awarded tens of thousands of pounds in damages. “These trials took place against an onslaught of political, military and media slurs of Iraqis bringing spurious claims, and strident criticism of us, as lawyers, representing them. Yet we have just witnessed the rule of law in action,” said Sapna Malik, a partner at Leigh Day who represented two of the claimants.

Bethany, tentatively, shared this sense of vindication: “They were testing the facts – evidence of inhumane and degrading treatment. The court found that it was true and it amounted to a human rights violation. They found the witnesses credible. That’s really important.” Taken alongside the ICC’s preliminary assessment, this judgment demonstrated that not all the evidence submitted by Shiner and Public Interest Lawyers comprised of bogus claims from fakers, as had been suggested.

Meanwhile, in Basra, hopes for a genuine reckoning are receding. The city is the largest in southern Iraq, rich in natural resources such as oil, but today it is still run by mafias, a legacy of British occupation when armed militias and religious groups flourished. “People in Basra are always angry at the British army, for the simple reason that it did not fulfil its promises of bringing us stability, prosperity, construction, and turning Basra into a wonderful city,” says Khalaf. “The British have tried to buy people by providing some compensation to those whose property was destroyed. But none of us ever really believed Britain would try its army and soldiers.”