'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Saturday, 31 March 2018

Friday, 30 March 2018

What's with the sanctimony, Mr Waugh?

Osman Samiuddin in Cricinfo

Bless our stars, Steve Waugh has weighed in. From his pedestal, perched atop a great moral altitude, he spoke down to us.

"Like many, I'm deeply troubled by the events in Cape Town this last week, and acknowledge the thousands of messages I have received, mostly from heartbroken cricket followers worldwide.

"The Australian Cricket team has always believed it could win in any situation against any opposition, by playing combative, skillful and fair cricket, driven by our pride in the fabled Baggy Green.

"I have no doubt the current Australian team continues to believe in this mantra, however some have now failed our culture, making a serious error of judgement in the Cape Town Test match."

You'll have picked up by now that this was not going to be what it should have been: a mea culpa. "Sorry folks, Cape Town - my bad." One can hope for the tone, but one can't ever imagine such economy with the words.

Waugh's statement was a bid to recalibrate the Australian cricket's team moral compass, and you know, it would have been nice if he acknowledged his role in setting it awry in the first place. Because there can't be any doubt that a clean, straight line runs from the explosion-implosion of Cape Town back to that "culture" that Waugh created for his team, the one cricket gets so reverential about.

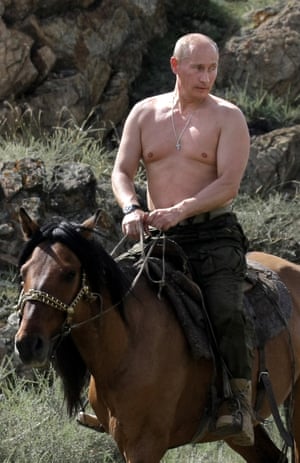

First, though, a little pre-reading prep, or YouTube wormholing, just to establish the moral frame within which we are operating. Start with this early in Waugh's international career - claiming a catch at point he clearly dropped off Kris Srikkanth. This was the 1985-86 season and he was young and the umpire spotted it and refused to give it out. So go here. This was ten years later, also at point, and he dropped Brian Lara, though he made as if he juggled and caught it. The umpire duped, Lara gone.![]() Steve Waugh: sanctimonious or statesman-like? Depends on which side of the "line" you stand on Getty Images

Steve Waugh: sanctimonious or statesman-like? Depends on which side of the "line" you stand on Getty Images

A man is not merely the sum of his incidents, and neither does he go through life unchanged. Waugh must have gone on to evolve, right? He became captain of Australia and soon it became clear that he had - all together now, in Morgan Freeman's voice - A Vision. There was a way he wanted his team to play the game.

He spelt it out in 2003, though all it was was a modification of the MCC's existing Spirit of Cricket doctrine. There were commitments to upholding player behaviour, and to how they treated the opposition and umpires, whose decisions they vowed to accept "as a mark of respect for our opponents, the umpires, ourselves and the game".

They would "value honesty and accept that every member of the team has a role to play in shaping and abiding by our shared standards and expectations".

Sledging or abuse would not be condoned. It wasn't enough that Australia played this way - Waugh expected others to do so as well. Here's Nasser Hussain, straight-talking in his memoir on the 2002-03 Ashes in Australia:

"I just think that about this time, he [Waugh] had lost touch with reality a bit he gave me the impression that he had forgotten what playing cricket was like for everyone other than Australia. He became a bit of a preacher. A bit righteous. It was like he expected everyone to do it the Aussie way because their way was the only way."

It was also duplicitous because the Aussie way Waugh was preaching was rarely practised on field by him or his team. So if Hussain refused to walk in the Boxing Day Test in 2002 after Jason Gillespie claimed a catch - with unanimous support from his team - well, you could hardly blame him, right, given Waugh was captain? YouTube wasn't around then, but not much got past Hussain on the field and the chances of those two "catches" having done so are low.

"Waugh created a case for Australian exceptionalism that has become every bit as distasteful, nauseating and divisive as that of American foreign policy"

As for the sledging that Waugh and his men agreed to not condone, revisit Graeme Smith's comments from the first time he played Australia, in 2001-02, with Waugh as captain. There's no need to republish it here but you can read about it (and keep kids away from the screen). It's not clever.

No, Waugh's sides didn't really show that much respect to opponents, unless their version of respect was Glenn McGrath asking Ramnaresh Sarwan - who was getting on top of Australia - what a specific part of Brian Lara's anatomy (no prizes for guessing which one) tasted like.

That incident, in Antigua, is especially instructive today because David Warner v Quinton de Kock is an exact replica. Sarwan's response, referencing McGrath's wife, was reprehensible, just as de Kock's was. But there was zilch recognition from either Warner or McGrath that they had initiated, or gotten involved in, something that could lead to such a comeback, or that their definition of "personal" was, frankly, too fluid and ill-defined for anyone's else's liking.

Waugh wasn't the ODI captain at the time of Darren Lehmann's racist outburstagainst Sri Lanka. Lehmann's captain, however, was Ricky Ponting, Waugh protege and torchbearer of values (and co-creator of the modified Spirit document), and so, historically, this was very much the Waugh era. As an aside, Lehmann's punishment was a five-ODI ban, imposed on him eventually by the ICC; no further sanctions from CA.

It's clear now that this modified code was the Australians drawing their "line", except the contents of the paper were - and continued to be - rendered irrelevant by their actions. The mere existence of it, in Australia's heads, has been enough.

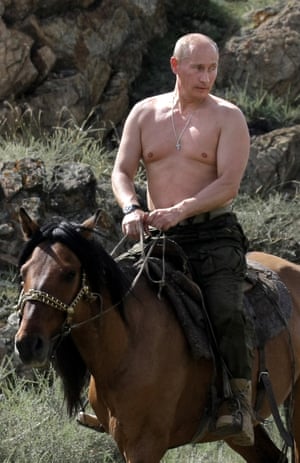

You've got to marvel at the conceit of them taking a universal code and unilaterally modifying it primarily for themselves, not in discussion with, you know, the many other non-Australian stakeholders in cricket - who might view the spirit of the game differently, if at all they give any importance to it - and expecting them to adhere to it.![]() They won trophies, but not hearts Getty Images

They won trophies, but not hearts Getty Images

It's why Warner and McGrath not only could not take it being dished back, but that they saw something intrinsically wrong in receiving it and not dishing it out. It's why it was fine to sledge Sourav Ganguly on rumours about his private life, but Ganguly turning up to the toss late was, in Waugh's words, "disrespectful" - to the game, of course, not him.

Waugh created a case for Australian exceptionalism, which has become every bit as distasteful, nauseating and divisive as that of American foreign policy. Look at the varnish of formality in dousing the true implication of "mental disintegration"; does "illegal combatants" ring a bell?

What took hold after Waugh was not what he preached but what he practised. One of my favourite examples is this lesser-remembered moment involving Justin Langer, a Waugh acolyte through and through, and his surreptitious knocking-off of a bail in Sri Lanka. Whatever he was trying to do, it wasn't valuing honesty as Waugh's code wanted.

Naturally the mind is drawn to the bigger, more infamous occasions, such as the behaviour of Ponting and his side that prompted a brave and stirring calling outby Peter Roebuck. That was two years before Ponting's virtual bullying of Aleem Dar after a decision went against Australia in the Ashes. It sure was a funny way to accept the umpire's decision. Ponting loved pushing another virtuous ploy that could so easily have been a Waugh tenet: of entering into gentlemen's agreements with opposing captains and taking the fielder's word for a disputed catch. Not many opposition captains did, which was telling of the virtuousness sides ascribed to Australia.

That this happened a decade or so ago should, if nothing else, confirm that Cape Town isn't just about the culture within this side - this is a legacy, passed on from the High Priest of Righteousness, Steve Waugh, to Ponting to Michael Clarke to Steve Smith, leaders of a long list of Australian sides that may have been good, bad and great but have been consistently unloved.

It's fair to be sceptical of real change. The severity of CA's sanctions - in response to public outrage and not the misdemeanour itself - amount to another bit of righteous oneupmanship. We remove captains for ball-tampering, what do you do? We, the rest of the world, let the ICC deal with them as per the global code for such things, and in that time the sky didn't fall. Now, on the back of CA's actions, David Richardson wants tougher punishments, thus continuing the ICC's strategy of policy-making based solely on incidents from series involving the Big Three.

Waugh was a great batsman. He was the captain of a great side. The only fact to add to this is that he played the game with great sanctimony. That helps explains why Australia now are where they are.

Bless our stars, Steve Waugh has weighed in. From his pedestal, perched atop a great moral altitude, he spoke down to us.

"Like many, I'm deeply troubled by the events in Cape Town this last week, and acknowledge the thousands of messages I have received, mostly from heartbroken cricket followers worldwide.

"The Australian Cricket team has always believed it could win in any situation against any opposition, by playing combative, skillful and fair cricket, driven by our pride in the fabled Baggy Green.

"I have no doubt the current Australian team continues to believe in this mantra, however some have now failed our culture, making a serious error of judgement in the Cape Town Test match."

You'll have picked up by now that this was not going to be what it should have been: a mea culpa. "Sorry folks, Cape Town - my bad." One can hope for the tone, but one can't ever imagine such economy with the words.

Waugh's statement was a bid to recalibrate the Australian cricket's team moral compass, and you know, it would have been nice if he acknowledged his role in setting it awry in the first place. Because there can't be any doubt that a clean, straight line runs from the explosion-implosion of Cape Town back to that "culture" that Waugh created for his team, the one cricket gets so reverential about.

First, though, a little pre-reading prep, or YouTube wormholing, just to establish the moral frame within which we are operating. Start with this early in Waugh's international career - claiming a catch at point he clearly dropped off Kris Srikkanth. This was the 1985-86 season and he was young and the umpire spotted it and refused to give it out. So go here. This was ten years later, also at point, and he dropped Brian Lara, though he made as if he juggled and caught it. The umpire duped, Lara gone.

A man is not merely the sum of his incidents, and neither does he go through life unchanged. Waugh must have gone on to evolve, right? He became captain of Australia and soon it became clear that he had - all together now, in Morgan Freeman's voice - A Vision. There was a way he wanted his team to play the game.

He spelt it out in 2003, though all it was was a modification of the MCC's existing Spirit of Cricket doctrine. There were commitments to upholding player behaviour, and to how they treated the opposition and umpires, whose decisions they vowed to accept "as a mark of respect for our opponents, the umpires, ourselves and the game".

They would "value honesty and accept that every member of the team has a role to play in shaping and abiding by our shared standards and expectations".

Sledging or abuse would not be condoned. It wasn't enough that Australia played this way - Waugh expected others to do so as well. Here's Nasser Hussain, straight-talking in his memoir on the 2002-03 Ashes in Australia:

"I just think that about this time, he [Waugh] had lost touch with reality a bit he gave me the impression that he had forgotten what playing cricket was like for everyone other than Australia. He became a bit of a preacher. A bit righteous. It was like he expected everyone to do it the Aussie way because their way was the only way."

It was also duplicitous because the Aussie way Waugh was preaching was rarely practised on field by him or his team. So if Hussain refused to walk in the Boxing Day Test in 2002 after Jason Gillespie claimed a catch - with unanimous support from his team - well, you could hardly blame him, right, given Waugh was captain? YouTube wasn't around then, but not much got past Hussain on the field and the chances of those two "catches" having done so are low.

"Waugh created a case for Australian exceptionalism that has become every bit as distasteful, nauseating and divisive as that of American foreign policy"

As for the sledging that Waugh and his men agreed to not condone, revisit Graeme Smith's comments from the first time he played Australia, in 2001-02, with Waugh as captain. There's no need to republish it here but you can read about it (and keep kids away from the screen). It's not clever.

No, Waugh's sides didn't really show that much respect to opponents, unless their version of respect was Glenn McGrath asking Ramnaresh Sarwan - who was getting on top of Australia - what a specific part of Brian Lara's anatomy (no prizes for guessing which one) tasted like.

That incident, in Antigua, is especially instructive today because David Warner v Quinton de Kock is an exact replica. Sarwan's response, referencing McGrath's wife, was reprehensible, just as de Kock's was. But there was zilch recognition from either Warner or McGrath that they had initiated, or gotten involved in, something that could lead to such a comeback, or that their definition of "personal" was, frankly, too fluid and ill-defined for anyone's else's liking.

Waugh wasn't the ODI captain at the time of Darren Lehmann's racist outburstagainst Sri Lanka. Lehmann's captain, however, was Ricky Ponting, Waugh protege and torchbearer of values (and co-creator of the modified Spirit document), and so, historically, this was very much the Waugh era. As an aside, Lehmann's punishment was a five-ODI ban, imposed on him eventually by the ICC; no further sanctions from CA.

It's clear now that this modified code was the Australians drawing their "line", except the contents of the paper were - and continued to be - rendered irrelevant by their actions. The mere existence of it, in Australia's heads, has been enough.

You've got to marvel at the conceit of them taking a universal code and unilaterally modifying it primarily for themselves, not in discussion with, you know, the many other non-Australian stakeholders in cricket - who might view the spirit of the game differently, if at all they give any importance to it - and expecting them to adhere to it.

It's why Warner and McGrath not only could not take it being dished back, but that they saw something intrinsically wrong in receiving it and not dishing it out. It's why it was fine to sledge Sourav Ganguly on rumours about his private life, but Ganguly turning up to the toss late was, in Waugh's words, "disrespectful" - to the game, of course, not him.

Waugh created a case for Australian exceptionalism, which has become every bit as distasteful, nauseating and divisive as that of American foreign policy. Look at the varnish of formality in dousing the true implication of "mental disintegration"; does "illegal combatants" ring a bell?

What took hold after Waugh was not what he preached but what he practised. One of my favourite examples is this lesser-remembered moment involving Justin Langer, a Waugh acolyte through and through, and his surreptitious knocking-off of a bail in Sri Lanka. Whatever he was trying to do, it wasn't valuing honesty as Waugh's code wanted.

Naturally the mind is drawn to the bigger, more infamous occasions, such as the behaviour of Ponting and his side that prompted a brave and stirring calling outby Peter Roebuck. That was two years before Ponting's virtual bullying of Aleem Dar after a decision went against Australia in the Ashes. It sure was a funny way to accept the umpire's decision. Ponting loved pushing another virtuous ploy that could so easily have been a Waugh tenet: of entering into gentlemen's agreements with opposing captains and taking the fielder's word for a disputed catch. Not many opposition captains did, which was telling of the virtuousness sides ascribed to Australia.

That this happened a decade or so ago should, if nothing else, confirm that Cape Town isn't just about the culture within this side - this is a legacy, passed on from the High Priest of Righteousness, Steve Waugh, to Ponting to Michael Clarke to Steve Smith, leaders of a long list of Australian sides that may have been good, bad and great but have been consistently unloved.

It's fair to be sceptical of real change. The severity of CA's sanctions - in response to public outrage and not the misdemeanour itself - amount to another bit of righteous oneupmanship. We remove captains for ball-tampering, what do you do? We, the rest of the world, let the ICC deal with them as per the global code for such things, and in that time the sky didn't fall. Now, on the back of CA's actions, David Richardson wants tougher punishments, thus continuing the ICC's strategy of policy-making based solely on incidents from series involving the Big Three.

Waugh was a great batsman. He was the captain of a great side. The only fact to add to this is that he played the game with great sanctimony. That helps explains why Australia now are where they are.

Saturday, 24 March 2018

The Indian Muslim is dealing with a silent, undeclared psychological war that the State has unleashed on it.

Irena Akbar in The Indian Express

This year, I did not want to serve ‘them’ biryani on Eid. But that is not our ‘tehzeeb’, our culture, my father insisted. So, on June 26, one guest after another – some among them likely BJP voters – visited us and relished the biryani, the qorma, and the kebabs. This, as the image of Junaid haunted me – his body soaked with blood, after he was lynched in front of a silent, complicit crowd of 200 in a train in Delhi.

Our guests on the day of Eid had absolutely nothing to do with what Junaid suffered, and I hate and condemn myself for resenting them. This wasn’t me. This isn’t me. And I wonder at the distance my heart has travelled from exactly a year ago, when I would be filled with excitement at our whole family preparing dishes for our Hindu guests (we have no Muslim guests for Eid as they are busy in their homes). Not too long ago, when I used to work in Delhi, I would sometimes carry a pot of biryani from Lucknow after Eid for my non-Muslim colleagues and friends. The sight of Hindus enjoying Mughlai/Awadhi cuisine at Karim’s in Delhi or Tunday Kababi in Lucknow swelled me with pride at our Ganga-Jamuni culture.

So, why did I now begin to resent a woman with a bindi on her forehead or a man with a kalava tied to his wrist enjoying a kebab at Tunday Kababi? Because I suspect he/she hates me. Hates my people. Hates the Muslim owners and cooks of Tunday even though he/she loves their food. Loves it that they had to shut shop during the crackdown on meat suppliers in UP. Loves it when the business of Muslim butchers is stifled even though he/she buys meat from them. Hates my co-religionists who wear topis and grow beards. Loves it when they are lynched in trains, in the fields, on the highway, inside their homes. Hates women who wear burkhas but pretends to support them on triple talaq. Shares fake videos about ‘evil’ Muslims on WhatsApp. Rejoices at the arrest of 15 Muslims after India’s loss to Pakistan in a cricket match on the basis of a false complaint.

No, I don’t hate them. They hate me. I am only angry they hate me. And I resent them for their hatred towards me. They pretend to fear me and my people, but in reality, it is I, and my people, who fear them. We are 14 per cent, they are close to 80, so we are the ones surrounded by the mob. And I fear that in their hatred, they will support the mob if it lynches yet another Muslim. Or, they will vote for a party that felicitates the killers or those who incite them to such murders by giving them Z-Security or a ticket to contest elections. I dread the plans that such parties may have already drafted for late 2018 or early 2019, a few months before the next general elections.

These fears are not exaggerated or unfounded. Between Akhlaque in 2015 and Junaid in 2017, each time a Muslim has been lynched in this country, every other Indian Muslim has died a slow death. The death of her confidence in the State which is supposed to protect her but doesn’t, the death of her trust in fellow countrymen who keep voting for the unabashedly anti-Muslim BJP, the death of her will to dispel the fears of the majority, and assure them that she is not the ‘other’, the ‘enemy’, but as Indian or even as human as they are.

I am acutely aware that not every Hindu is a supporter of Hindutva. His vote for the BJP could be based on promises of vikas, or the incompetence of other parties. As a Muslim, I am painfully aware of the pressure of stereotyping. I have lost count of the number of times I have asked non-Muslims to look at me, at their Muslim neighbours, friends and co-workers, at their Muslim tailors, at Muslim actors and filmmakers to clear their misconceptions about us being terror sympathisers.

So, when my mind slips into the realm of stereotyping, I pull it back and look at my Hindu neighbour whose NGO employs underprivileged Muslim women, at my Hindu cook who did not take a single day off during Ramzan and would prepare iftaar for us, at the Hindus who helped me put together an art exhibition I recently curated, at my former Hindu colleagues who supported me when I was going through a rough patch, at my Facebook newsfeed filled with posts by liberal Hindus denouncing cow terrorism, at the writers who returned their awards to protest against Akhlaque’s killing in 2015, at the recent Not In My Name protests triggered by Junaid’s murder.

This year, I did not want to serve ‘them’ biryani on Eid. But that is not our ‘tehzeeb’, our culture, my father insisted. So, on June 26, one guest after another – some among them likely BJP voters – visited us and relished the biryani, the qorma, and the kebabs. This, as the image of Junaid haunted me – his body soaked with blood, after he was lynched in front of a silent, complicit crowd of 200 in a train in Delhi.

Our guests on the day of Eid had absolutely nothing to do with what Junaid suffered, and I hate and condemn myself for resenting them. This wasn’t me. This isn’t me. And I wonder at the distance my heart has travelled from exactly a year ago, when I would be filled with excitement at our whole family preparing dishes for our Hindu guests (we have no Muslim guests for Eid as they are busy in their homes). Not too long ago, when I used to work in Delhi, I would sometimes carry a pot of biryani from Lucknow after Eid for my non-Muslim colleagues and friends. The sight of Hindus enjoying Mughlai/Awadhi cuisine at Karim’s in Delhi or Tunday Kababi in Lucknow swelled me with pride at our Ganga-Jamuni culture.

So, why did I now begin to resent a woman with a bindi on her forehead or a man with a kalava tied to his wrist enjoying a kebab at Tunday Kababi? Because I suspect he/she hates me. Hates my people. Hates the Muslim owners and cooks of Tunday even though he/she loves their food. Loves it that they had to shut shop during the crackdown on meat suppliers in UP. Loves it when the business of Muslim butchers is stifled even though he/she buys meat from them. Hates my co-religionists who wear topis and grow beards. Loves it when they are lynched in trains, in the fields, on the highway, inside their homes. Hates women who wear burkhas but pretends to support them on triple talaq. Shares fake videos about ‘evil’ Muslims on WhatsApp. Rejoices at the arrest of 15 Muslims after India’s loss to Pakistan in a cricket match on the basis of a false complaint.

No, I don’t hate them. They hate me. I am only angry they hate me. And I resent them for their hatred towards me. They pretend to fear me and my people, but in reality, it is I, and my people, who fear them. We are 14 per cent, they are close to 80, so we are the ones surrounded by the mob. And I fear that in their hatred, they will support the mob if it lynches yet another Muslim. Or, they will vote for a party that felicitates the killers or those who incite them to such murders by giving them Z-Security or a ticket to contest elections. I dread the plans that such parties may have already drafted for late 2018 or early 2019, a few months before the next general elections.

These fears are not exaggerated or unfounded. Between Akhlaque in 2015 and Junaid in 2017, each time a Muslim has been lynched in this country, every other Indian Muslim has died a slow death. The death of her confidence in the State which is supposed to protect her but doesn’t, the death of her trust in fellow countrymen who keep voting for the unabashedly anti-Muslim BJP, the death of her will to dispel the fears of the majority, and assure them that she is not the ‘other’, the ‘enemy’, but as Indian or even as human as they are.

I am acutely aware that not every Hindu is a supporter of Hindutva. His vote for the BJP could be based on promises of vikas, or the incompetence of other parties. As a Muslim, I am painfully aware of the pressure of stereotyping. I have lost count of the number of times I have asked non-Muslims to look at me, at their Muslim neighbours, friends and co-workers, at their Muslim tailors, at Muslim actors and filmmakers to clear their misconceptions about us being terror sympathisers.

So, when my mind slips into the realm of stereotyping, I pull it back and look at my Hindu neighbour whose NGO employs underprivileged Muslim women, at my Hindu cook who did not take a single day off during Ramzan and would prepare iftaar for us, at the Hindus who helped me put together an art exhibition I recently curated, at my former Hindu colleagues who supported me when I was going through a rough patch, at my Facebook newsfeed filled with posts by liberal Hindus denouncing cow terrorism, at the writers who returned their awards to protest against Akhlaque’s killing in 2015, at the recent Not In My Name protests triggered by Junaid’s murder.

Citizens hold placards during a silent protest ” Not in My Name ” against the targeted lynching, at Jantar Mantar in New Delhi. (Source: PTI Photo)

The mind of an ordinary Indian Muslim like me is caught in a constant tug-of-war – pulled by fear on one end, and by hope on the other. When my heart sank at the killing of Junaid, a faint glimmer of hope also emerged. The outraged liberal, secular Hindu got out of his social media mode and onto the streets to protest the lynching of Muslims being carried out in his name, under the banner ‘Not In My Name’. It was a reassuring moment for the besieged Indian Muslim, and she wholeheartedly supported it, joining in the protests, much like American Muslims who joined the Whites in the ‘IamMuslim’ protests in the US following Trump’s ‘Muslim ban’.

The next day, the Prime Minister disapproved of killing in the name of the cow. But a few hours later, another Muslim, Alimuddin Ansari, was lynched in the name of the cow in Jharkhand. He was violently thrashed and his face held up in front of the camera — as if it were a trophy — before his killers dealt him the final deathblows. The incident has strengthened the pull of fear against the pull of hope in the mental tug of war for the Muslim.

When a community is alienated and demonised consistently, its members often just retract to their shells. Most Muslims fear expressing themselves freely on social media, and avoid political discussions in offices, RWA meetings and kitty parties, and some are even wary of carrying non-vegetarian food on trains. When we drive past cows roaming the streets of Lucknow, we are careful not to get too close. No, we are not a paranoid family. Other Muslims have expressed similar caution. A Hindu can afford to slouch in his seat if the National Anthem is being played in a cinema hall, but remember how a Muslim family was forced out of a theatre in Mumbai for allegedly doing the same?

The Indian Muslim is dealing with a silent, undeclared psychological war that the State has unleashed on it. This war’s strategy is clear: Demonise the Muslim in the mind of the Hindu in some form or the other – the cow-eater, the ‘love jihadi’ on the prowl for Hindu girls, the anti-national who won’t chant ‘Bharat Mata ki jai’, the monstrous husband who divorces his wife via instant triple talaq, the descendant of the ‘rabid anti-Hindu’ ruler Aurangzeb, etc. Use chest-thumping TV anchors and fake videos on WhatsApp to set the discussions for the living rooms of the urban Hindu, or the chaupals of the rural Hindu. The overwhelming majority of Hindus is peace-loving, so it will react by keeping distance from the “horrible Muslims” and vote against “pseudo-secular” parties. But the violent, jobless youth may catch hold of a Muslim farmer, or a young boy wearing a topi, and beat him to death. That these youths are glorified as ‘gau rakshaks’ and not penalised emboldens them.

But cleverly, such murders are not done together at one time and at one place. As Pratap Bhanu Mehta wrote in The Indian Express, ‘A big riot would concentrate the mind, make a damning headline. A protracted riot in slow motion, individual victims across different states, simply makes this appear another daily routine.’ Once the Muslim has been demonised, corner him further. Don’t wish him for Eid. Boycott the iftaar held by the President. Shame him for not saying ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ (sorry, the Urdu ‘Hindustan Zindabad’ doesn’t work), and do politics over yoga-namaaz, Ramzan-Diwali, shamshaanghaat-qabristaan. Send the message loud and clear to the Muslim: ‘You, your vote don’t matter.’ And send the message to the Hindu: ‘Muslims have been finally shown their place after 1,000 years of subjugation of Hindus by Muslim rulers. You have won. You are safe.’

Thus, the mind of the majority, the Hindus, is quietly and successfully diverted from the real issues that matter to them as Indian citizens — development, jobs, investments, ‘achche din’. No chest-thumping TV anchor shouts down panellists over the lack of jobs. Everyone is only talking cows, beef, and triple talaq. The diversionary tactics of the State have also taken away the mind of the Muslim from what matters to him as an Indian citizen – development and jobs. All that matters to the Muslim now is his right to a life of dignity and safety, one that is led without fear. Something the ‘New India’ is snatching away from him.

The mind of an ordinary Indian Muslim like me is caught in a constant tug-of-war – pulled by fear on one end, and by hope on the other. When my heart sank at the killing of Junaid, a faint glimmer of hope also emerged. The outraged liberal, secular Hindu got out of his social media mode and onto the streets to protest the lynching of Muslims being carried out in his name, under the banner ‘Not In My Name’. It was a reassuring moment for the besieged Indian Muslim, and she wholeheartedly supported it, joining in the protests, much like American Muslims who joined the Whites in the ‘IamMuslim’ protests in the US following Trump’s ‘Muslim ban’.

The next day, the Prime Minister disapproved of killing in the name of the cow. But a few hours later, another Muslim, Alimuddin Ansari, was lynched in the name of the cow in Jharkhand. He was violently thrashed and his face held up in front of the camera — as if it were a trophy — before his killers dealt him the final deathblows. The incident has strengthened the pull of fear against the pull of hope in the mental tug of war for the Muslim.

When a community is alienated and demonised consistently, its members often just retract to their shells. Most Muslims fear expressing themselves freely on social media, and avoid political discussions in offices, RWA meetings and kitty parties, and some are even wary of carrying non-vegetarian food on trains. When we drive past cows roaming the streets of Lucknow, we are careful not to get too close. No, we are not a paranoid family. Other Muslims have expressed similar caution. A Hindu can afford to slouch in his seat if the National Anthem is being played in a cinema hall, but remember how a Muslim family was forced out of a theatre in Mumbai for allegedly doing the same?

The Indian Muslim is dealing with a silent, undeclared psychological war that the State has unleashed on it. This war’s strategy is clear: Demonise the Muslim in the mind of the Hindu in some form or the other – the cow-eater, the ‘love jihadi’ on the prowl for Hindu girls, the anti-national who won’t chant ‘Bharat Mata ki jai’, the monstrous husband who divorces his wife via instant triple talaq, the descendant of the ‘rabid anti-Hindu’ ruler Aurangzeb, etc. Use chest-thumping TV anchors and fake videos on WhatsApp to set the discussions for the living rooms of the urban Hindu, or the chaupals of the rural Hindu. The overwhelming majority of Hindus is peace-loving, so it will react by keeping distance from the “horrible Muslims” and vote against “pseudo-secular” parties. But the violent, jobless youth may catch hold of a Muslim farmer, or a young boy wearing a topi, and beat him to death. That these youths are glorified as ‘gau rakshaks’ and not penalised emboldens them.

But cleverly, such murders are not done together at one time and at one place. As Pratap Bhanu Mehta wrote in The Indian Express, ‘A big riot would concentrate the mind, make a damning headline. A protracted riot in slow motion, individual victims across different states, simply makes this appear another daily routine.’ Once the Muslim has been demonised, corner him further. Don’t wish him for Eid. Boycott the iftaar held by the President. Shame him for not saying ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ (sorry, the Urdu ‘Hindustan Zindabad’ doesn’t work), and do politics over yoga-namaaz, Ramzan-Diwali, shamshaanghaat-qabristaan. Send the message loud and clear to the Muslim: ‘You, your vote don’t matter.’ And send the message to the Hindu: ‘Muslims have been finally shown their place after 1,000 years of subjugation of Hindus by Muslim rulers. You have won. You are safe.’

Thus, the mind of the majority, the Hindus, is quietly and successfully diverted from the real issues that matter to them as Indian citizens — development, jobs, investments, ‘achche din’. No chest-thumping TV anchor shouts down panellists over the lack of jobs. Everyone is only talking cows, beef, and triple talaq. The diversionary tactics of the State have also taken away the mind of the Muslim from what matters to him as an Indian citizen – development and jobs. All that matters to the Muslim now is his right to a life of dignity and safety, one that is led without fear. Something the ‘New India’ is snatching away from him.

Wednesday, 21 March 2018

Should the Big Four accountancy firms be split up?

Natasha Landell-Mills and Jim Peterson in The Financial Times

Yes - Separating audit from consulting would prevent conflicts of interest.

Auditors are failing investors. The situation has become so dire that last week the head of the UK’s accounting watchdog said it was time to consider forcing audit firms to divest their substantial and lucrative consulting work, writes Natasha Landell-Mills.

This shift from the Financial Reporting Council, which opposed the idea six years ago, is welcome. But breaking up the Big Four accountancy firms — PwC, KPMG, EY and Deloitte — can only be a first step. Lasting reform depends on auditors working for shareholders, not management.

Auditors are supposed to underpin trust in financial markets. Major stock markets require listed companies to hire auditors to verify their accounts, providing reassurance to shareholders that material matters have been inspected and their capital is protected. In the UK, auditors must certify that the published numbers give a “true and fair view” of circumstances and income; that they have been prepared in accordance with accounting standards; and that they comply with company law.

But audit is failing to meet investors’ expectations. The failure of Carillion, linked to aggressive accounting, is just the latest high profile example. And this is not just a UK phenomenon. The International Forum of Independent Audit Regulators found that 40 per cent of the audits it inspected were sub-standard.

Multiple market failures need to be addressed. The most obvious problem is that audit quality is invisible to those whom it is intended to benefit: the shareholders. It is difficult to differentiate good and bad audits. Even with the introduction of extended auditor reports in the UK (and starting in 2019 in the US), formulaic notes about audit risks often hide more than they convey.

Even when questions are raised about the quality of audits, shareholders almost always vote to retain auditors, with most receiving at least 95 per cent support. Last year, 97 per cent of Carillion shareholders voted to re-appoint KPMG. Lack of scrutiny creates space for conflicts of interest. Auditors who feel accountable to company executives rather than shareholders will be less likely to challenge them. These conflicts are exacerbated when audit firms also sell other services to management teams, particularly if that consultancy work is more profitable.

The dominance of the Big Four in large company audits is another concern: when large and powerful firms are able to crowd out high quality competitors, the damage is lasting.

Taken together, these failures have resulted in a dysfunctional audit market that needs a broad revamp. Splitting audit from consulting would prevent the most insidious conflict of interest. When non-audit work makes up around 80 per cent of fee income for the Big Four (and just over half of income from audit clients), the influence of this part of the business is huge.

Current limits on consulting work have not eliminated this problem. They are often set too high or can be gamed, while auditors can still be influenced by the hope of winning non-audit work after they relinquish the audit mandate.

There is quite simply no compelling reason why shareholders should accept these conflicts and the resulting risks to audit quality introduced by non-audit work. But other reforms are necessary.

Auditors should provide meaningful disclosures about the risks they uncover. They need to verify that company accounts do not overstate performance and capital and that unrealised profits are disclosed.

Engagement between shareholders and audit committees and auditors should become the norm, not the exception. Shareholders need to scrutinise accounting and audit performance, and use their votes to remove auditors or audit committee directors where performance is substandard.

Finally, the accounting watchdogs must be far more robust on audit quality and impose meaningful sanctions. Even the best intentioned will struggle against a broken system.

No — Lopping off advisory services would hurt performance

The recent spate of large-scale corporate accounting scandals is deeply worrying and raises a familiar question: “Where were the auditors?” But the correct answer does not involve breaking up the four professional services firms that dominate auditing, writes Jim Peterson.

Forcing Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC to shed their non-audit businesses would neither add competition nor boost smaller competitors. Lopping off the Big Four’s consulting and advisory services would degrade their performance, weaken them financially, and hamper their ability to meet the needs of their clients and the capital markets.

Although the UK regulator is raising competition concerns, the root problem is global. The growth of the Big Four, operating in more than 100 countries, reflects their multinational clients’ needs for breadth of geographic presence and specialised industry expertise.

The yawning gap in size between the Big Four and their smaller peers has long since grown beyond closure: even the smallest, KPMG, took in $26.4bn in 2017, three times as much as BDO, its next nearest competitor. If pressed, risk managers of the smaller firms admit to lacking the skills and the risk tolerance even to consider bidding to audit a far-flung multinational.

The suggestion that competition and choice would be increased by splitting up the Big Four is doubly unrealistic. Forcing them to spin off their non-auditing business would not create any new auditors. We would continue to see dilemmas like the one faced by BT last year when it set out to replace PwC after a £530m discrepancy was uncovered in the accounts of its Italian division. The UK telecoms group ended up picking KPMG for want of alternatives, even though BT’s chairman had previously been global chairman of KPMG.

Similarly, Japan’s Toshiba tossed EY in favour of PwC in 2016, only to suffer disagreements with the second firm — this led to delays in its financial statements and an eventual qualified audit report. Wish as it might, Toshiba has no further choices, because of business-based conflicts on the part of Deloitte and KPMG.

A split by industry sector — say, assigning auditing of banking and technology to Firm A-1, while manufacturing and energy go to new Firm A-2 — would be no better. Each sector would still be served by just four big firms. If each firm were split in half, the two smaller firms would struggle to amass the expertise, personnel and capital necessary to provide the level of service that big companies expect.

Splitting auditing from advisory work is a solution in search of a problem. Many jurisdictions, including the UK, EU and US, restrict the ability of firms to cross-sell other services to their audit clients. Concerns about inherent conflicts of interest are overblown.

The enthusiasm for cutting up the Big Four also fails to recognise how the world is changing. The rise of artificial intelligence, blockchain and robotics is reshaping the way information is gathered and verified. Auditors will need more — rather than less — expertise.

Warehouse inventories, crop yields and wind farms will soon be surveyed rapidly and comprehensively in ways that could easily displace the tedious and partial sampling done for decades by squadrons of young audit staff. But to take advantage of these advances, auditors need to have the scale, the financial strength and the technical skills to develop and offer them.

These tools will also deliver data that management needs for operational and strategic decision making. If auditors are to be barred from providing this kind of advisory work, the legitimacy of methods that have prevailed since the Victorian era is under threat. Investors will require some sort of audit function, but who would provide it? Splitting up the Big Four will achieve nothing if they fail and are replaced by arms of Amazon and Google.

Auditors should be held accountable for their mistakes, but these issues are too complex for simplistic solutions. Rather than a quick amputation, we need a full-scale re-engineering of the current model with all of its parts.

Yes - Separating audit from consulting would prevent conflicts of interest.

Auditors are failing investors. The situation has become so dire that last week the head of the UK’s accounting watchdog said it was time to consider forcing audit firms to divest their substantial and lucrative consulting work, writes Natasha Landell-Mills.

This shift from the Financial Reporting Council, which opposed the idea six years ago, is welcome. But breaking up the Big Four accountancy firms — PwC, KPMG, EY and Deloitte — can only be a first step. Lasting reform depends on auditors working for shareholders, not management.

Auditors are supposed to underpin trust in financial markets. Major stock markets require listed companies to hire auditors to verify their accounts, providing reassurance to shareholders that material matters have been inspected and their capital is protected. In the UK, auditors must certify that the published numbers give a “true and fair view” of circumstances and income; that they have been prepared in accordance with accounting standards; and that they comply with company law.

But audit is failing to meet investors’ expectations. The failure of Carillion, linked to aggressive accounting, is just the latest high profile example. And this is not just a UK phenomenon. The International Forum of Independent Audit Regulators found that 40 per cent of the audits it inspected were sub-standard.

Multiple market failures need to be addressed. The most obvious problem is that audit quality is invisible to those whom it is intended to benefit: the shareholders. It is difficult to differentiate good and bad audits. Even with the introduction of extended auditor reports in the UK (and starting in 2019 in the US), formulaic notes about audit risks often hide more than they convey.

Even when questions are raised about the quality of audits, shareholders almost always vote to retain auditors, with most receiving at least 95 per cent support. Last year, 97 per cent of Carillion shareholders voted to re-appoint KPMG. Lack of scrutiny creates space for conflicts of interest. Auditors who feel accountable to company executives rather than shareholders will be less likely to challenge them. These conflicts are exacerbated when audit firms also sell other services to management teams, particularly if that consultancy work is more profitable.

The dominance of the Big Four in large company audits is another concern: when large and powerful firms are able to crowd out high quality competitors, the damage is lasting.

Taken together, these failures have resulted in a dysfunctional audit market that needs a broad revamp. Splitting audit from consulting would prevent the most insidious conflict of interest. When non-audit work makes up around 80 per cent of fee income for the Big Four (and just over half of income from audit clients), the influence of this part of the business is huge.

Current limits on consulting work have not eliminated this problem. They are often set too high or can be gamed, while auditors can still be influenced by the hope of winning non-audit work after they relinquish the audit mandate.

There is quite simply no compelling reason why shareholders should accept these conflicts and the resulting risks to audit quality introduced by non-audit work. But other reforms are necessary.

Auditors should provide meaningful disclosures about the risks they uncover. They need to verify that company accounts do not overstate performance and capital and that unrealised profits are disclosed.

Engagement between shareholders and audit committees and auditors should become the norm, not the exception. Shareholders need to scrutinise accounting and audit performance, and use their votes to remove auditors or audit committee directors where performance is substandard.

Finally, the accounting watchdogs must be far more robust on audit quality and impose meaningful sanctions. Even the best intentioned will struggle against a broken system.

No — Lopping off advisory services would hurt performance

The recent spate of large-scale corporate accounting scandals is deeply worrying and raises a familiar question: “Where were the auditors?” But the correct answer does not involve breaking up the four professional services firms that dominate auditing, writes Jim Peterson.

Forcing Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC to shed their non-audit businesses would neither add competition nor boost smaller competitors. Lopping off the Big Four’s consulting and advisory services would degrade their performance, weaken them financially, and hamper their ability to meet the needs of their clients and the capital markets.

Although the UK regulator is raising competition concerns, the root problem is global. The growth of the Big Four, operating in more than 100 countries, reflects their multinational clients’ needs for breadth of geographic presence and specialised industry expertise.

The yawning gap in size between the Big Four and their smaller peers has long since grown beyond closure: even the smallest, KPMG, took in $26.4bn in 2017, three times as much as BDO, its next nearest competitor. If pressed, risk managers of the smaller firms admit to lacking the skills and the risk tolerance even to consider bidding to audit a far-flung multinational.

The suggestion that competition and choice would be increased by splitting up the Big Four is doubly unrealistic. Forcing them to spin off their non-auditing business would not create any new auditors. We would continue to see dilemmas like the one faced by BT last year when it set out to replace PwC after a £530m discrepancy was uncovered in the accounts of its Italian division. The UK telecoms group ended up picking KPMG for want of alternatives, even though BT’s chairman had previously been global chairman of KPMG.

Similarly, Japan’s Toshiba tossed EY in favour of PwC in 2016, only to suffer disagreements with the second firm — this led to delays in its financial statements and an eventual qualified audit report. Wish as it might, Toshiba has no further choices, because of business-based conflicts on the part of Deloitte and KPMG.

A split by industry sector — say, assigning auditing of banking and technology to Firm A-1, while manufacturing and energy go to new Firm A-2 — would be no better. Each sector would still be served by just four big firms. If each firm were split in half, the two smaller firms would struggle to amass the expertise, personnel and capital necessary to provide the level of service that big companies expect.

Splitting auditing from advisory work is a solution in search of a problem. Many jurisdictions, including the UK, EU and US, restrict the ability of firms to cross-sell other services to their audit clients. Concerns about inherent conflicts of interest are overblown.

The enthusiasm for cutting up the Big Four also fails to recognise how the world is changing. The rise of artificial intelligence, blockchain and robotics is reshaping the way information is gathered and verified. Auditors will need more — rather than less — expertise.

Warehouse inventories, crop yields and wind farms will soon be surveyed rapidly and comprehensively in ways that could easily displace the tedious and partial sampling done for decades by squadrons of young audit staff. But to take advantage of these advances, auditors need to have the scale, the financial strength and the technical skills to develop and offer them.

These tools will also deliver data that management needs for operational and strategic decision making. If auditors are to be barred from providing this kind of advisory work, the legitimacy of methods that have prevailed since the Victorian era is under threat. Investors will require some sort of audit function, but who would provide it? Splitting up the Big Four will achieve nothing if they fail and are replaced by arms of Amazon and Google.

Auditors should be held accountable for their mistakes, but these issues are too complex for simplistic solutions. Rather than a quick amputation, we need a full-scale re-engineering of the current model with all of its parts.

Tuesday, 20 March 2018

Kevin Pietersen

Jonathan Liew in The Independent

At 11am on May 12, 2015, Andrew Strauss was unveiled as the new director of England cricket on the Lord’s balcony, in front of a horseshoe of photographers and camera crews.

At exactly the same time, on the other side of London, Kevin Pietersen was walking out to bat for Surrey against Leicestershire at The Oval, 326 not out overnight. By the time Strauss had finished his first interview with Sky Sports News, explaining why he was extinguishing Pietersen’s last realistic hope of playing international cricket, the man himself had moved on to 351.

It was the first and last triple-century of Pietersen’s career. Scarcely, if ever, has an innings been more auspiciously timed. Scarcely has English cricket’s fundamental duality – between inside and outside, genteel and chaotic, starched shirts and grubby whites, polished words and pure filthy deed – been more starkly depicted.

Above all, it underlined the basic and inalienable Pietersen trait, one that will likely follow him to the grave: his immaculate sense of occasion. Scarcely, if ever, has there been a cricketer who timed his interventions to such devastatingly maximal effect.

Pietersen finished his timely knock on 355 not out (Getty)

“You’re not God,” he memorably told Yuvraj Singh during the Mohali Test of 2008. “You’re a cricketer. And I’m a better one.”

Here again, on a glorious spring morning in London, Pietersen was once again proving that whatever you had to say, he could – and would – say it louder.

---

In hindsight, it would have been brilliantly fitting if that scintillating innings of 355 had been Pietersen’s last in first-class cricket: one final, pointless, valedictory V-sign to the English game before he rode into a franchised sunset. But it wasn’t.

Instead, Pietersen’s last ever game in whites came a few weeks later, a rain-ruined draw against Lancashire. He came in at No4, scratched around for a few minutes, and then edged a vicious lifter to slip off Kyle Jarvis for two. The cameras picked him out in the Surrey dressing room, his gaze drawn to the England v New Zealand Test match on television rather than the drab game unfolding in front of him. Right to the very last, Pietersen never bothered to disguise his disdain for the domestic game, its mixed standard, its modest horizons, what he called the “county cricketcomfort zone”.

And so, with England turning its back on Pietersen, Pietersen turned his back on England, spending the last three years of his career travelling the world playing Twenty20. St Lucia Zouks, Dolphins, Melbourne Stars, Quetta Gladiators, Rising Pune Supergiants, Surrey: over time, they all began to blend into each other, the same adoring crowds, the same airport departure lounges, the same arcade game of thrill or bust.

You might almost say Pietersen found his own comfort zone in the end.

By the end of the professional career he finally brought to an end this week, he was a good T20 player, not a great one. The rapidly evolving format was beginning to leave him behind. His low dot-ball percentage, traditionally one of his biggest strengths, was beginning to creep up. Pune, his Indian Premier League franchise, released him at the end of 2016 and with little interest ahead of the 2017 auction, Pietersen decided to pre-emptively withdraw rather than risk the humiliation of going unsold.

Weirdly, T20 always seemed an imperfect fit for Pietersen’s remarkable and cadenced range of talents. Yes: like many others, he could belt it miles, and belt it often. But unlike them, he could also do it for hours, for days, and often after doing very little of note for months. Test cricket, with its epic scope, its wild fluctuations in texture and tempo, was always the most appropriate stage for him. He knew it, too. When he was on song, Pietersen could play as loudly as anyone who has picked up a bat. But somehow, it was the quietness that made it so devastating.

Most remarkably, Pietersen never won any of the franchise competitions he competed in: not the Big Bash or the IPL, not the Caribbean Premier League or the Blast, not the Ram Slam or the PSL. Here, perhaps, lies the greatest irony of all. Pietersen’s only winner’s medal in the format where he eventually focused his energies came in England blue, at the World Twenty20 in 2010. His only triumph was also ours.

For all the bad blood and the rancour, all the fraught meetings and snide briefings, the knives in the back and the knives in the front, the essential truth about Pietersen and England was this: they were stronger together, and weaker apart.

You don’t need me to talk you through Pietersen’s greatest innings for England. You know them already: the 202 and the 186, the 149 and the 227, the 91 off 65, the 158, the 158, the 158. But the innings Pietersen always rated as his greatest was the 151 he made against Sri Lanka in Colombo in 2012, in 45 degree heat and 100 per cent humidity, with a bat that was slipping in his gloves, a haze so intense it was blurring his vision.

As he swept, clubbed and reverse-swept Sri Lanka’s spinners all around the wicket, an intense serenity, an invincible quiet, seemed to settle over him. As he would later write in his book ‘On Cricket’, the Colombo knock stands out because unlike so many other of his great innings there was nothing flamboyant or bellicose about it: just pure, blissful batting. So much of Pietersen’s England career felt like war. This felt like peace.

Pietersen played brilliantly against Sri Lanka in Colombo (Getty)

Great art has dreadful manners, as Simon Schama puts it. Perhaps the same applies to great sport: it slaps you around the face, kicks you in the groin, demands that you acclaim it. That was as true of Pietersen off the field as it was on it. Having left home as a teenage off-spinner and fought his way to the very top of the game, he was ruthlessly intolerant of anybody who didn’t share his fierce work ethic and relentless standards.

He never really understood the point of county cricket. He never really learned to hold his tongue and keep his opinions to himself. This was Pietersen’s way – the natural product of a tough Afrikaner childhood in which even the most minor indiscipline would be punished with a swipe of his farmer’s “army stick” – and you could get in line, or you could go to hell.

English cricket – and England in general – is not quite as tolerant and broad-minded as it likes to think it is. The frequent refrain you will hear about Pietersen is that he falls out with people everywhere he goes. The implication, that Pietersen is an inveterate troublemaker who could start a fight in an empty room, is only really part of the story. Pietersen’s unapologetic ‘otherness’ made him as much a target as a protagonist.

Strauss remembers his first encounter with Pietersen, a county game between Middlesex and Nottinghamshire in 2000. As soon as he arrived at the crease, the Middlesex wicket-keeper David Nash began to single out the young newcomer for abuse. Instead of simply ignoring it, Pietersen marched to the square-leg umpire and demanded he put a stop to it. The insult Nash kept using to Pietersen was “doos”.

And ultimately, Pietersen was English cricket’s ultimate outsider: by turns painfully awkward, wracked by self-doubt, beguiled by attention and yet capable of great generosity. As his final first-class game petered out at The Oval, Pietersen ventured unbidden out of the dressing room to sign hundreds of autographs for young fans on the boundary edge: not a TV camera or a PR enabler in sight, just a star and his adoring public, each getting exactly what they wanted.

Pietersen’s relationship with the England team was similarly transactional. It is fashionable to lament those lost years after the 2013-14 Ashes, decry the bitter rift that his sacking opened up within the game, chastise the ECB for their lack of indulgence. But ultimately, they got almost a decade of service out of a brilliant player who helped them win four Ashes series, an India tour and a global tournament. When they had had enough, they simply discarded him. The regime survived. The edifice remained intact.

They won.

Strauss called an end to Pietersen’s England career (Getty)

What of Pietersen? He got to play a game he loved for two decades. He got to travel the world. He won caps, broke records. He got to captain his country and thrill millions. His determination to grasp the opportunities offered by franchise T20 and unwillingness to compromise on his attacking, confrontational approach cost him his career, but virtually everything the ECB has done since is a tacit admission that he was right all along.

Pietersen won, too.

“It’s your nation, not mine,” Pietersen once quipped to a British interview in a magazine interview. And it is no surprise, really, that as his relationship with the English game began to unravel, he began to seek refuge in the supranational: his wildlife projects, his family, his social media sycophants, the golden fist bump of the global T20 community. Ultimately, Pietersen and English cricket were too different in temperament and culture ever to be more than a fleeting entanglement.

The miracle, really, is that they managed to keep the show on the road for so long. And as the dust finally settles, as time breathes its heavy sigh on one of the great England careers, perhaps that will ultimately be Pietersen’s epitaph. When it all came together, nothing on earth could compare. Remember him that way, not the way it ended.

At 11am on May 12, 2015, Andrew Strauss was unveiled as the new director of England cricket on the Lord’s balcony, in front of a horseshoe of photographers and camera crews.

At exactly the same time, on the other side of London, Kevin Pietersen was walking out to bat for Surrey against Leicestershire at The Oval, 326 not out overnight. By the time Strauss had finished his first interview with Sky Sports News, explaining why he was extinguishing Pietersen’s last realistic hope of playing international cricket, the man himself had moved on to 351.

It was the first and last triple-century of Pietersen’s career. Scarcely, if ever, has an innings been more auspiciously timed. Scarcely has English cricket’s fundamental duality – between inside and outside, genteel and chaotic, starched shirts and grubby whites, polished words and pure filthy deed – been more starkly depicted.

Above all, it underlined the basic and inalienable Pietersen trait, one that will likely follow him to the grave: his immaculate sense of occasion. Scarcely, if ever, has there been a cricketer who timed his interventions to such devastatingly maximal effect.

Pietersen finished his timely knock on 355 not out (Getty)

“You’re not God,” he memorably told Yuvraj Singh during the Mohali Test of 2008. “You’re a cricketer. And I’m a better one.”

Here again, on a glorious spring morning in London, Pietersen was once again proving that whatever you had to say, he could – and would – say it louder.

---

In hindsight, it would have been brilliantly fitting if that scintillating innings of 355 had been Pietersen’s last in first-class cricket: one final, pointless, valedictory V-sign to the English game before he rode into a franchised sunset. But it wasn’t.

Instead, Pietersen’s last ever game in whites came a few weeks later, a rain-ruined draw against Lancashire. He came in at No4, scratched around for a few minutes, and then edged a vicious lifter to slip off Kyle Jarvis for two. The cameras picked him out in the Surrey dressing room, his gaze drawn to the England v New Zealand Test match on television rather than the drab game unfolding in front of him. Right to the very last, Pietersen never bothered to disguise his disdain for the domestic game, its mixed standard, its modest horizons, what he called the “county cricketcomfort zone”.

And so, with England turning its back on Pietersen, Pietersen turned his back on England, spending the last three years of his career travelling the world playing Twenty20. St Lucia Zouks, Dolphins, Melbourne Stars, Quetta Gladiators, Rising Pune Supergiants, Surrey: over time, they all began to blend into each other, the same adoring crowds, the same airport departure lounges, the same arcade game of thrill or bust.

You might almost say Pietersen found his own comfort zone in the end.

By the end of the professional career he finally brought to an end this week, he was a good T20 player, not a great one. The rapidly evolving format was beginning to leave him behind. His low dot-ball percentage, traditionally one of his biggest strengths, was beginning to creep up. Pune, his Indian Premier League franchise, released him at the end of 2016 and with little interest ahead of the 2017 auction, Pietersen decided to pre-emptively withdraw rather than risk the humiliation of going unsold.

Weirdly, T20 always seemed an imperfect fit for Pietersen’s remarkable and cadenced range of talents. Yes: like many others, he could belt it miles, and belt it often. But unlike them, he could also do it for hours, for days, and often after doing very little of note for months. Test cricket, with its epic scope, its wild fluctuations in texture and tempo, was always the most appropriate stage for him. He knew it, too. When he was on song, Pietersen could play as loudly as anyone who has picked up a bat. But somehow, it was the quietness that made it so devastating.

Most remarkably, Pietersen never won any of the franchise competitions he competed in: not the Big Bash or the IPL, not the Caribbean Premier League or the Blast, not the Ram Slam or the PSL. Here, perhaps, lies the greatest irony of all. Pietersen’s only winner’s medal in the format where he eventually focused his energies came in England blue, at the World Twenty20 in 2010. His only triumph was also ours.

For all the bad blood and the rancour, all the fraught meetings and snide briefings, the knives in the back and the knives in the front, the essential truth about Pietersen and England was this: they were stronger together, and weaker apart.

You don’t need me to talk you through Pietersen’s greatest innings for England. You know them already: the 202 and the 186, the 149 and the 227, the 91 off 65, the 158, the 158, the 158. But the innings Pietersen always rated as his greatest was the 151 he made against Sri Lanka in Colombo in 2012, in 45 degree heat and 100 per cent humidity, with a bat that was slipping in his gloves, a haze so intense it was blurring his vision.

As he swept, clubbed and reverse-swept Sri Lanka’s spinners all around the wicket, an intense serenity, an invincible quiet, seemed to settle over him. As he would later write in his book ‘On Cricket’, the Colombo knock stands out because unlike so many other of his great innings there was nothing flamboyant or bellicose about it: just pure, blissful batting. So much of Pietersen’s England career felt like war. This felt like peace.

Pietersen played brilliantly against Sri Lanka in Colombo (Getty)

Great art has dreadful manners, as Simon Schama puts it. Perhaps the same applies to great sport: it slaps you around the face, kicks you in the groin, demands that you acclaim it. That was as true of Pietersen off the field as it was on it. Having left home as a teenage off-spinner and fought his way to the very top of the game, he was ruthlessly intolerant of anybody who didn’t share his fierce work ethic and relentless standards.

He never really understood the point of county cricket. He never really learned to hold his tongue and keep his opinions to himself. This was Pietersen’s way – the natural product of a tough Afrikaner childhood in which even the most minor indiscipline would be punished with a swipe of his farmer’s “army stick” – and you could get in line, or you could go to hell.

English cricket – and England in general – is not quite as tolerant and broad-minded as it likes to think it is. The frequent refrain you will hear about Pietersen is that he falls out with people everywhere he goes. The implication, that Pietersen is an inveterate troublemaker who could start a fight in an empty room, is only really part of the story. Pietersen’s unapologetic ‘otherness’ made him as much a target as a protagonist.

Strauss remembers his first encounter with Pietersen, a county game between Middlesex and Nottinghamshire in 2000. As soon as he arrived at the crease, the Middlesex wicket-keeper David Nash began to single out the young newcomer for abuse. Instead of simply ignoring it, Pietersen marched to the square-leg umpire and demanded he put a stop to it. The insult Nash kept using to Pietersen was “doos”.

And ultimately, Pietersen was English cricket’s ultimate outsider: by turns painfully awkward, wracked by self-doubt, beguiled by attention and yet capable of great generosity. As his final first-class game petered out at The Oval, Pietersen ventured unbidden out of the dressing room to sign hundreds of autographs for young fans on the boundary edge: not a TV camera or a PR enabler in sight, just a star and his adoring public, each getting exactly what they wanted.

Pietersen’s relationship with the England team was similarly transactional. It is fashionable to lament those lost years after the 2013-14 Ashes, decry the bitter rift that his sacking opened up within the game, chastise the ECB for their lack of indulgence. But ultimately, they got almost a decade of service out of a brilliant player who helped them win four Ashes series, an India tour and a global tournament. When they had had enough, they simply discarded him. The regime survived. The edifice remained intact.

They won.

Strauss called an end to Pietersen’s England career (Getty)

What of Pietersen? He got to play a game he loved for two decades. He got to travel the world. He won caps, broke records. He got to captain his country and thrill millions. His determination to grasp the opportunities offered by franchise T20 and unwillingness to compromise on his attacking, confrontational approach cost him his career, but virtually everything the ECB has done since is a tacit admission that he was right all along.

Pietersen won, too.

“It’s your nation, not mine,” Pietersen once quipped to a British interview in a magazine interview. And it is no surprise, really, that as his relationship with the English game began to unravel, he began to seek refuge in the supranational: his wildlife projects, his family, his social media sycophants, the golden fist bump of the global T20 community. Ultimately, Pietersen and English cricket were too different in temperament and culture ever to be more than a fleeting entanglement.

The miracle, really, is that they managed to keep the show on the road for so long. And as the dust finally settles, as time breathes its heavy sigh on one of the great England careers, perhaps that will ultimately be Pietersen’s epitaph. When it all came together, nothing on earth could compare. Remember him that way, not the way it ended.

EU tickled pink as Brexit red lines turn green

John Crace in The Guardian

“Je suis très heureux,” Michel Barnier began. It soon became clear why he was so heureux as the text of the draft transitional agreement appeared on a screen behind him during his Brussels press conference with David Davis. Large chunks of it were highlighted in green. These were Theresa May’s red lines. Green was now the new red.

The British prime minister had been right in insisting that large sections of the Brexit deal would be non-negotiable. She just hadn’t made it clear that it would be the EU that was refusing to negotiate. So on almost every point that Britain had said it wouldn’t be giving in, it had given in.

Barnier made a token effort to sound as if he wasn’t crowing that British objections to money, trade negotiations, the European court of justice, fishing rights and the length of the transitional deal had all been casually brushed aside. But when you are as heureux as he is then it’s hard to keep a straight visage.

Not that everything was done and dusted, the EU chief negotiator continued. Mais non! There was still 25% of the draft agreement that wasn’t green. These were the bits that were in yellow and white. The yellow areas were the red lines that the British government couldn’t quite yet bring itself to turn green but would probably do so in the next couple of weeks.

The white areas were slightly more problematic. These were the red lines – principally over Northern Ireland – the British government knew it would eventually have to turn green, but as yet had no clear idea of how to do so without every Brexiter in the Tory party having a complete meltdown about being sold out.

But this wasn’t his problem, because in the absence of the white lines turning green then the backstop was to keep Northern Ireland in the customs union and the single market. In other words, business comme d’habitude.

Or no business comme d’habitude as there was next to no chance of Britain reaching any of the 750 new trade deals it needed to get done in a couple of months. Not least when the EU was committed to a go-slow on its own negotiations. Bonne chance avec that. If Britain wanted to turn itself from a rule giver to a rule taker then it was no peau off his nez. No wonder Barnier was heureux as Larry.

Davis wasn’t nearly so heureux, though he tried to look as if he was. His fixed grin looked suspiciously like rigor mortis. He too declared himself to be thrilled so many of the red lines had turned green and looked forward to making all the necessary concessions to turn the yellow and white ones green. People just had to understand that Brexit was a simple dialectic. To take back control you had to give back control. To get a transition period you needed a standstill.

The longer the Brexit secretary spoke, the more miserable he appeared. There are limits even to his self-delusion. Britain had got nearly everything it had asked for, he said unconvincingly. Take the transition period. The UK had asked for two years ending in March 2021 and the EU had argued for December 2020. So they had compromised at December 2020. As for Northern Ireland, he really didn’t have a clue. Only that in some lights at certain times of day, red could sometimes look a bit green.

Why had the EU and the UK chosen to highlight the agreed sections in green and not some other colour, a reporter asked. By now Davis was catatonically unheureux, so it was Barnier who replied. He would have been happy with bleu, blanc or rouge but every time he tried writing something in rouge the British kept turning it vert. And anyway he quite liked vert. Besides, green was the perfect description of the British negotiating team.

“Je suis très heureux,” Michel Barnier began. It soon became clear why he was so heureux as the text of the draft transitional agreement appeared on a screen behind him during his Brussels press conference with David Davis. Large chunks of it were highlighted in green. These were Theresa May’s red lines. Green was now the new red.

The British prime minister had been right in insisting that large sections of the Brexit deal would be non-negotiable. She just hadn’t made it clear that it would be the EU that was refusing to negotiate. So on almost every point that Britain had said it wouldn’t be giving in, it had given in.

Barnier made a token effort to sound as if he wasn’t crowing that British objections to money, trade negotiations, the European court of justice, fishing rights and the length of the transitional deal had all been casually brushed aside. But when you are as heureux as he is then it’s hard to keep a straight visage.

Not that everything was done and dusted, the EU chief negotiator continued. Mais non! There was still 25% of the draft agreement that wasn’t green. These were the bits that were in yellow and white. The yellow areas were the red lines that the British government couldn’t quite yet bring itself to turn green but would probably do so in the next couple of weeks.

The white areas were slightly more problematic. These were the red lines – principally over Northern Ireland – the British government knew it would eventually have to turn green, but as yet had no clear idea of how to do so without every Brexiter in the Tory party having a complete meltdown about being sold out.

But this wasn’t his problem, because in the absence of the white lines turning green then the backstop was to keep Northern Ireland in the customs union and the single market. In other words, business comme d’habitude.

Or no business comme d’habitude as there was next to no chance of Britain reaching any of the 750 new trade deals it needed to get done in a couple of months. Not least when the EU was committed to a go-slow on its own negotiations. Bonne chance avec that. If Britain wanted to turn itself from a rule giver to a rule taker then it was no peau off his nez. No wonder Barnier was heureux as Larry.

Davis wasn’t nearly so heureux, though he tried to look as if he was. His fixed grin looked suspiciously like rigor mortis. He too declared himself to be thrilled so many of the red lines had turned green and looked forward to making all the necessary concessions to turn the yellow and white ones green. People just had to understand that Brexit was a simple dialectic. To take back control you had to give back control. To get a transition period you needed a standstill.

The longer the Brexit secretary spoke, the more miserable he appeared. There are limits even to his self-delusion. Britain had got nearly everything it had asked for, he said unconvincingly. Take the transition period. The UK had asked for two years ending in March 2021 and the EU had argued for December 2020. So they had compromised at December 2020. As for Northern Ireland, he really didn’t have a clue. Only that in some lights at certain times of day, red could sometimes look a bit green.

Why had the EU and the UK chosen to highlight the agreed sections in green and not some other colour, a reporter asked. By now Davis was catatonically unheureux, so it was Barnier who replied. He would have been happy with bleu, blanc or rouge but every time he tried writing something in rouge the British kept turning it vert. And anyway he quite liked vert. Besides, green was the perfect description of the British negotiating team.

Sunday, 18 March 2018

The runaway locomotive of Electronic Voting Machines

Tabish Khair in The Hindu