Thomas Frank in The Guardian

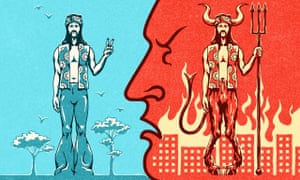

Illustration by Matt Kenyon

So our billionaire president hangs a portrait of Andrew Jackson on his wall, spits on his hands, and takes a sledgehammer to the Dodd–Frank Act. The portrait is of the banks’ all-time arch-enemy; the reality is that the banks are going to be deregulated yet again. And in that insane juxtaposition we can grasp rightwing populism almost in its entirety: fiery verbal hostility to elites, combined with generous government favours for those same elites.

Donald Trump’s adviser Stephen Bannon presents an even more striking combination. A former executive at Goldman Sachs, Bannon is also the product of what the Hollywood Reporter calls a “blue-collar, union and Democratic family” who feels “an unreconstructed sense of class awareness, or bitterness – or betrayal”. Bannon is a founding member of the objectionable far-right website Breitbart and an architect of Trump’s unlikely victory, the man at the right hand of power. And yet almost no one in Washington seems to understand how he pulled this off.

Let me propose a partial explanation: that one of the reasons Bannon succeeded is because he has been able to unite the two unconnected halves of American populist outrage – the cultural and the economic.

Start with the latter. In a 2014 interview on the recent financial crisis, Bannon proclaimed: “The way that the people who ran the banks and ran the hedge funds have never really been held accountable for what they did has fuelled much of the anger in the Tea Party movement in the United States.”

Fair enough. I myself am outraged that financiers were not held responsible for the many obvious mistakes and even acts of fraud they appeared to commit.

But when we turn to the specifics of Bannon’s indictment, accountability gets a little blurry. In 2010 Bannon wrote, directed and produced a documentary film about the 2008 financial crisis called Generation Zero – a documentary that explicitly tries to get laissez-faire capitalism off the hook for this colossal capitalist disaster. Remember the roll-back of banking rules under Bill Clinton and George W Bush, or the hapless regulatory agencies filled with former bank officers and lobbyists? Evidently none of that really mattered. As one of the movie’s many experts intones, “Deregulation is not the problem.” The first sentence in the promotional copy on the back of the DVD case is just as blunt: “The current economic crisis is not a failure of capitalism, but a failure of culture.”

So our billionaire president hangs a portrait of Andrew Jackson on his wall, spits on his hands, and takes a sledgehammer to the Dodd–Frank Act. The portrait is of the banks’ all-time arch-enemy; the reality is that the banks are going to be deregulated yet again. And in that insane juxtaposition we can grasp rightwing populism almost in its entirety: fiery verbal hostility to elites, combined with generous government favours for those same elites.

Donald Trump’s adviser Stephen Bannon presents an even more striking combination. A former executive at Goldman Sachs, Bannon is also the product of what the Hollywood Reporter calls a “blue-collar, union and Democratic family” who feels “an unreconstructed sense of class awareness, or bitterness – or betrayal”. Bannon is a founding member of the objectionable far-right website Breitbart and an architect of Trump’s unlikely victory, the man at the right hand of power. And yet almost no one in Washington seems to understand how he pulled this off.

Let me propose a partial explanation: that one of the reasons Bannon succeeded is because he has been able to unite the two unconnected halves of American populist outrage – the cultural and the economic.

Start with the latter. In a 2014 interview on the recent financial crisis, Bannon proclaimed: “The way that the people who ran the banks and ran the hedge funds have never really been held accountable for what they did has fuelled much of the anger in the Tea Party movement in the United States.”

Fair enough. I myself am outraged that financiers were not held responsible for the many obvious mistakes and even acts of fraud they appeared to commit.

But when we turn to the specifics of Bannon’s indictment, accountability gets a little blurry. In 2010 Bannon wrote, directed and produced a documentary film about the 2008 financial crisis called Generation Zero – a documentary that explicitly tries to get laissez-faire capitalism off the hook for this colossal capitalist disaster. Remember the roll-back of banking rules under Bill Clinton and George W Bush, or the hapless regulatory agencies filled with former bank officers and lobbyists? Evidently none of that really mattered. As one of the movie’s many experts intones, “Deregulation is not the problem.” The first sentence in the promotional copy on the back of the DVD case is just as blunt: “The current economic crisis is not a failure of capitalism, but a failure of culture.”

What culture do you think Bannon means? The buccaneering culture of the Wall Street traders? The corrupt culture of the real estate appraisers or the bond rating agencies? The get-rich-quick culture of the mortgage originators?

No, no and no. He means … the counterculture of the 1960s. Bell bottoms. Drum solos. Dope. That’s the thing to blame for the financial crisis and the bailouts. Not the deregulation of derivatives in 2000. It was those kids having fun at Woodstock in 1969.

I am not joking. This really is Bannon’s argument, illustrated again and again in Generation Zero with 40-year-old footage of hippies dancing and fooling around, which is thrown together with stock footage of dollar bills being counted, or funny old cartoons, or vacant houses, or really mean-looking sharks, and then back to those happy hippies again.

One way of assessing this is that Generation Zero is the transition from the culture wars to Trumpism. What Bannon is doing is bringing the strands of outrage together. He’s saying that the culture wars and the financial crisis both share the same villain: the bad values that supposedly infected our society in the 1960s. The same forces that made the movies and pop music so vulgar also crashed the economy and ruined your livelihood. Here is how Roger Kimball of the New Criterion makes the case in Generation Zero:

“A lot of what we have just seen is a kind of a real-world dramatisation of those ideas that became popular in the 60s and 70s, and that had a dry run then. And that, I think, has been a prescription for disaster in some very concrete ways. Take, for example, the financial crisis. What we have just seen in the irresponsible lending by banks and the irresponsible leveraging by many hedge funds is an abdication of responsibility.”

That gives you a taste of how Bannon’s logic unfolds. The decade of the 60s supposedly introduced Americans to the idea of irresponsibility and self-indulgence, and now that we are suffering from an epidemic of irresponsibility and self-indulgence a mere 50 years later, it’s obviously the fault of people from that decade long ago. Blame is thus offloaded from, say, the captured regulators of the Bush administration to the pot-smoking college students of the Vietnam era. Unfortunately, just because something makes moral sense doesn’t mean it’s true. Take the phenomenon of “stated income” or liar’s loans, the fraud that came to symbolise so much of what went wrong in the last decade. One of the movie’s experts, Peter Schweizer (later the author of Clinton Cash), seems to blame this dirty business on … Saul Alinsky, an author and community organiser who died in 1972. Alinsky, he maintains, “applauded activists who used lying effectively. You end up where applicants lie on their applications, mortgage lenders lie when they pass that to the underwriters, and then these mortgages are sold as mortgage-backed securities on Wall Street ... It’s a chain of lie after lie after lie, which eventually undermines even the most effective system.”

Schweizer is right that loans based on lies undermined the system. By 2005 they had become an enormous part of the mortgage market, and the story of how that happened is a really fascinating one. Many books have been written on the subject. But filmmaker Bannon shows no interest in any of that. He makes little effort to find out who was issuing such loans, what kind of houses they were used to purchase (McMansions?), who packaged them up into securities, or why regulators didn’t do anything to stop it. Instead, the movie just implies that the diabolical Alinsky had some vague something to do with it and then walks away. This is not history, it’s naked blame-shifting.

In fairness, Bannon’s movie also makes plenty of valid points and has some fine moments. The director obviously cares about the working-class people who were ruined by the recession. He correctly portrays the Democratic party’s love affair with Wall Street in the 90s (although he downplays the amorous deeds of Republicans). He understands the cronyism between government and high finance, and one of his sources aptly describes the bailed-out system as “socialism for the wealthy but capitalism for everybody else”. Which kind of sounds like something that old 60s radical Bernie Sanders might say.

The putative moral of Generation Zero is that we all need to grow up and take responsibility for our actions; and yet as I watched it I was bowled over by how profoundly irresponsible this documentary is. Other than a single quote from Time magazine circa 1969 and the old TV footage of hippies doing their dance, Bannon doesn’t really try to nail down what “the 60s” stood for or meant. None of the leading participants in that decade’s bacchanals are interviewed. Skipping ahead to the financial crisis, we never learn whether it’s the dishonest home-buyers who were hippies, or the fly-by-night mortgage lenders or the Wall Street traders who were hippies. Which set of hippies are we supposed to crack down on? We never find out.

All we know, really, is that there was once a dreadful thing called the 60s, and then there was a terrible financial crisis four decades later, and because the one came before the other, it somehow caused it. The effort to bridge that evidence gap is almost nonexistent. In a typical moment, Bannon shows us Republican treasury secretary Hank Paulson desperately trying to stop the money haemorrhage in September 2008, and then cuts immediately to footage of the Black Panthers, holding a rally many decades ago. Why? What is the connection? Does Paulson, the devout Christian Scientist, the teetotalling college football star, have some secret affiliation with 60s radicalism?

Worst of all is the former presidential adviser Dick Morris (Bill Clinton’s Steve Bannon, come to think of it), who appears throughout Generation Zero blowing hard about this outrage and that. Here is what Morris tells the camera about the threat of hyperinflation, which loomed so large in the rightwing mind back in 2010: “The real catastrophe is going to come in about a year, a year and a half, or two years, when all of this money that the Fed has been printing comes out of hiding all at once and causes explosive inflation.”

The movie’s most far-fetched proposition is also its most revealing. Generation Zero asserts that history unfolds in a cyclical pattern, endlessly repeating itself. Historical crises (such as the Depression and second world war) are said to give rise to triumphant and ambitious generations (think Levittown circa 1952), who make the mistake of spoiling their children, who then tear society apart through their decadence and narcissism, triggering the cycle over again. Or as the movie’s trailer puts it: “In history, there are four turnings. The crisis. The high. The awakening. The unravelling. History repeats itself. The untold story about the financial meltdown.”

In a word, the theory is ridiculous. It is so vague and squishy and easily contradicted that the viewer wonders why Bannon included it at all.

And then it hits you. He included it because this rainy-day Marxism is pretty much the only way you can do what Bannon set out to do in this movie: get deregulated capitalism out of the shadow for the financial crisis and blame instead the same forces that the family-values crowd has been complaining about for years. Blame the hippies for what arch-deregulator Phil Gramm did 40 years later and call it a high-flown theory of history: the “fourth turning”, or some such nonsense. Of course Bannon’s fans believe it. It makes perfect sense to them.

A funny thing about Bannon’s stinky pudding of exaggerations and hallucinations: in the broadest terms, it’s also true. The counterculture really did have something to do with both our accelerated modern capitalism and the Democratic party’s shift to the right – it’s a subject I have written about from The Conquest of Cool to Listen, Liberal.

The Clinton administration really did strike up an alliance with Wall Street, and this really did represent a new and catastrophic direction for the Democratic party. Trade deals really did help to deindustrialise the US, and that deindustrialisation really was a terrible thing. The bankers really did get bailed out by their friends the politicians in 2008 and 2009, and it really was the greatest outrage of our stupid century. And there really is a lot of narcissism mixed up in modern capitalism. Just look at the man for whom Bannon presently works.

Generation Zero acknowledges these visible facts but connects the dots by means of a vast looping diagram of confusion and blame evasion. It is a fantasy of accountability that actually serves to get the guilty off the hook.

Then again, another way to judge this alternative theory, with its alternative facts, is to set it off against what the Democratic establishment was saying at the time. Which was pretty much nothing.

Centrist Democrats simply don’t talk about their alliance with Wall Street – it’s like the party’s guilty secret, never to be discussed in a straightforward way. Try asking former President Obama or former treasury secretary Geithner or former attorney general Holder why they were so generous with the bankers and why they never held them responsible, and see what kind of answer you get.

And that, in short, is the story of how the right captured the spirit of revolt in this most flagrantly populist period in modern times. Want to take it away from them, liberal? Start by understanding your history.