Ramachandra Guha in The Hindustan Times

Back in 2005, a knowledgeable Gujarati journalist wrote of how ‘Narendra Modi thinks a detergent named development will wash away the memory of 2002’. While focusing on new infrastructure and industrial projects in his state, the then chief minister of Gujarat launched what the journalist called ‘a massive self-publicity drive’, publishing calendars, booklets and posters where his own photograph appeared prominently alongside words and statistics speaking of Gujarat’s achievements under his leadership. ‘Modi has made sure that in Gujarat no one can escape noticing him,’ remarked the journalist.

Since May 2014, this self-publicity drive has been extended to the nation as a whole. In fact, the process began before the general elections, when, through social media and his speeches, Narendra Modi successfully projected himself as the sole and singular alternative to a (visibly) corrupt UPA regime. The BJP, a party previously opposed to ‘vyakti puja’, succumbed to the power of Modi’s personality. Since his swearing-in as Prime Minister, the government has done what the party did before it: totally subordinated itself to the will, and occasionally the whim, of a single individual.

Hero-worship is not uncommon in India. Indeed, we tend to excessively venerate high achievers in many fields. Consider the extraordinarily large and devoted fan following of Sachin Tendulkar and Lata Mangeshkar. These fans see their icons as flawless in a way fans in other countries do not. In America, Bob Dylan has many admirers but also more than a few critics. The same is true of the British tennis player Andy Murray. But in public discourse in India, criticism of Sachin and Lata is extremely rare. When offered, it tends to be met with vituperative abuse, not by rational or reasoned rebuttal.

The hero-worship of sportspeople is merely silly. But the hero-worship of politicians is inimical to democracy. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu were epicentres of progressive social reform, whose activists promoted caste and gender equality, rational thinking, and individual rights. Yet in more recent years, Maharashra has seen the cult of Bal Thackeray, Tamil Nadu the cult of J Jayalalithaa. In each case, the power of the State was (in Jayalalithaa’s case still is) put in service of this personality cult, with harassment and intimidation of critics being common.

However, at a nation-wide level the cult of Narendra Modi has had only one predecessor — that of Indira Gandhi. Thus now, as then, ruling party politicians demand that citizens see the Prime Minister as embodying not just the party or the government, but the nation itself. Millions of devotees on social media (as well as quite a few journalists) have succumbed to the most extreme form of hero-worship. More worryingly, one senior cabinet minister has called Narendra Modi a Messiah. A chief minister has insinuated that anyone who criticises the Prime Minister’s policies is anti-national. Meanwhile, as in Indira Gandhi’s time, the government’s publicity wing, as well as AIR and Doordarshan, works overtime to broadcast the Prime Minister’s image and achievements.

While viewing the promotion of this cult of Narendra Modi, I have been reminded of two texts by long-dead thinker-politicians, both (sadly) still relevant. The first is an essay published by Jawaharlal Nehru in 1937 under the pen-name of ‘Chanakya’. Here Nehru, referring to himself in the third person (as Modi often does now), remarked: ‘Jawaharlal cannot become a fascist. Yet he has all the makings of a dictator in him — a vast popularity, a strong will directed to a well-defined purpose, energy, pride, organisational capacity, ability, hardness, and, with all his love of the crowd, an intolerance of others and a certain contempt for the weak and the inefficient.’

Nehru was here issuing a warning to himself. Twelve years later, in his remarkable last speech to the Constituent Assembly, BR Ambedkar issued a warning to all Indians, when, invoking John Stuart Mill, he asked them not ‘to lay their liberties at the feet of even a great man, or to trust him with powers which enable him to subvert their institutions’. There was ‘nothing wrong’, said Ambedkar, ‘in being grateful to great men who have rendered life-long services to the country. But there are limits to gratefulness.’ He worried that in India, ‘Bhakti or what may be called the path of devotion or hero-worship, plays a part in its politics unequalled in magnitude by the part it plays in the politics of any other country in the world. Bhakti in religion may be a road to the salvation of the soul. But in politics, Bhakti or hero-worship is a sure road to degradation and to eventual dictatorship.’

These remarks uncannily anticipated the cult of Indira Gandhi and the Emergency. As I have written in these columns before, Indian democracy is now too robust to be destroyed by a single individual. But it can still be severely damaged. That is why this personality cult of Narendra Modi must be challenged (and checked) before it goes much further.

Later this week we shall observe the 60th anniversary of BR Ambedkar’s death. Some well-meaning (and brave) member of the Prime Minister’s inner circle should bring Ambedkar’s speech of 1949 to his attention. And perhaps Nehru’s pseudonymous article of 1937 too.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 4 December 2016

It's too late for globalisation – Kakistocracy is in fashion

Bob Swarup in The Guardian

The world is getting smaller. That is the unbidden meme of our generation, thanks to the juggernaut of growth unleashed by an outpouring of global bodies, free trade agreements, technology and international capital. Every business and person now has a global reach and audience.

Today’s paradigm is globalisation and free trade is its evangelical mantra.

But this narrative has become worn and no longer fits the facts. In recent months, there has been a backlash, accompanied by emotive talk about the reversal of globalisation and the battle for society’s future. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development used its latest health check on the global economy to warn of the costs of protectionism.

The hand-wringing is half a decade too late, because globalisation is already dead and we are already some miles into the journey back.

Donald Trump and Theresa May are not flagbearers in the distance, they are catapults battering at the walls. Trump’s stated intent to pull the US out of the TPP on his first day in office underlines the new reality we inhabit, as does the European Union’s recent troubles closing a trade agreement with Canada thanks to Wallonia’s obstinence.

Today, we have a new meme – deglobalisation – as people turn their backs on an interconnected world economy and societies turn iconoclastic.

It is not for the first time.

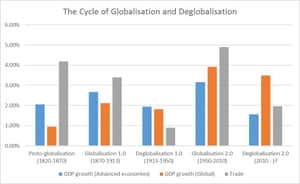

Globalisation may be defined as when trade across nations is growing faster than GDP. People interact more, transact more and create more wealth. Deglobalisation is the alternate state where trade grows less than GDP. Countries focus inwards, trade declines as a proportion of GDP and growth shrinks. A clear cycle of the two emerges over history.

Phases of globalisation and deglobalisation over the last two centuries. Illustration: Maddison, World Bank, Max Roser, CPB Netherlands, Camdor Global

Proto-globalisation (1820-1870): Rapid global trade growth, thanks to the Industrial Revolution and the spread of European colonial rule

Globalisation 1.0 (1870-1913): Empire building became the norm. Rapid advancements in transport and communications grew trade. But rapid change also meant volatile bouts of economic obsolescence and crisis

Deglobalisation 1.0 (1913-1950): Limited growth, unequal outcomes and a huge debt overhang from previous decades stoked economic nationalism and protectionism. Trade fell and a collective failure to tackle deeper structural issues led to the 1930s

Globalisation 2.0 (1950-2010): Since then, we have been on a tearaway expansion with unparalleled growth of both global trade and GDP

Deglobalisation 2.0 (2010-?): The last financial crisis focused policymaker attention inwards and crystallised the growing sense of social disenfranchisement. A toxic mix of suppressed wages, rocketing debt and political myopia have largely destroyed the allure of globalisation.

This is more than a sense of ennui. Global trade today is not slowing down but has plateaued – hardly a barometer of rude global health. After their peak in January 2015, global exports fell -1.6% by the end of August 2016. The blame lies not with commodity price falls, but shifts in trade policy. Protectionism is en vogue. Restrictive trade measures have outstripped liberalising measures three to one this year and increased by almost five times since 2009, as policymakers try to circumvent the WTO. Meanwhile, the deleveraging of banking balance sheets over recent years has hit global lending, as banks retreat from peripheral to core domestic activities, cutting vital credit flows through key arteries.

All of this preceded the populist deluge of 2016 and, indeed, contributed as policymakers myopically prioritised stability over social cohesion, ignoring the lessons of the past.

But globally, politicians are now fast realigning to shifting public moods. A year ago, to imagine a world where the major western leaders included Trump, the Brexit brigade and Marine Le Pen was the province of satire. Today, we are two-thirds there. Their ascendancy has shifted the political debate towards nativism in a hauntingly familiar nationalist narrative, as others follow suit.

Our new politics are not leftwing or rightwing, merely whether you are in this world or out of it. Even defenders of globalisation are falling into the same trap. By demonising those that voted against and not providing alternative options, they cling tighter to those that confirm and affirm their beliefs. That is still nativism of a different sort and still the politics of division, not unity.

This is Deglobalisation 2.0.

Monetary policies such as quantitative easing and its newborn sibling, fiscal easing, cannot change this dynamic. Absent structural change, their cumulative corrosive impact on savings and fillip to global debt ensure a limited runway and only inflame the rhetoric of disenfranchisement. Meanwhile, divorces are turning ugly as emotions override reason, viz the talk of Brexit fees and anti-dumping levies, the metaphorical Kristallnacht of populist victors like May and Trump as they struggle for coherence, and emerging divisions between central banks and politicians, to name but a few.

Democracy is fast turning to kakistocracy – government by the least qualified leaders. Globalisation is transmuting to nationalism. The effects are well documented in history – autarky, economic naivety, protectionism and a rush to grab what remains of the pie, only to trample it underfoot.

Me first always ends in me last. The world is still getting smaller, but just in our minds and horizons now, and thoughtless we risk becoming all the poorer for it.

The world is getting smaller. That is the unbidden meme of our generation, thanks to the juggernaut of growth unleashed by an outpouring of global bodies, free trade agreements, technology and international capital. Every business and person now has a global reach and audience.

Today’s paradigm is globalisation and free trade is its evangelical mantra.

But this narrative has become worn and no longer fits the facts. In recent months, there has been a backlash, accompanied by emotive talk about the reversal of globalisation and the battle for society’s future. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development used its latest health check on the global economy to warn of the costs of protectionism.

The hand-wringing is half a decade too late, because globalisation is already dead and we are already some miles into the journey back.

Donald Trump and Theresa May are not flagbearers in the distance, they are catapults battering at the walls. Trump’s stated intent to pull the US out of the TPP on his first day in office underlines the new reality we inhabit, as does the European Union’s recent troubles closing a trade agreement with Canada thanks to Wallonia’s obstinence.

Today, we have a new meme – deglobalisation – as people turn their backs on an interconnected world economy and societies turn iconoclastic.

It is not for the first time.

Globalisation may be defined as when trade across nations is growing faster than GDP. People interact more, transact more and create more wealth. Deglobalisation is the alternate state where trade grows less than GDP. Countries focus inwards, trade declines as a proportion of GDP and growth shrinks. A clear cycle of the two emerges over history.

Phases of globalisation and deglobalisation over the last two centuries. Illustration: Maddison, World Bank, Max Roser, CPB Netherlands, Camdor Global

Proto-globalisation (1820-1870): Rapid global trade growth, thanks to the Industrial Revolution and the spread of European colonial rule

Globalisation 1.0 (1870-1913): Empire building became the norm. Rapid advancements in transport and communications grew trade. But rapid change also meant volatile bouts of economic obsolescence and crisis

Deglobalisation 1.0 (1913-1950): Limited growth, unequal outcomes and a huge debt overhang from previous decades stoked economic nationalism and protectionism. Trade fell and a collective failure to tackle deeper structural issues led to the 1930s

Globalisation 2.0 (1950-2010): Since then, we have been on a tearaway expansion with unparalleled growth of both global trade and GDP

Deglobalisation 2.0 (2010-?): The last financial crisis focused policymaker attention inwards and crystallised the growing sense of social disenfranchisement. A toxic mix of suppressed wages, rocketing debt and political myopia have largely destroyed the allure of globalisation.

This is more than a sense of ennui. Global trade today is not slowing down but has plateaued – hardly a barometer of rude global health. After their peak in January 2015, global exports fell -1.6% by the end of August 2016. The blame lies not with commodity price falls, but shifts in trade policy. Protectionism is en vogue. Restrictive trade measures have outstripped liberalising measures three to one this year and increased by almost five times since 2009, as policymakers try to circumvent the WTO. Meanwhile, the deleveraging of banking balance sheets over recent years has hit global lending, as banks retreat from peripheral to core domestic activities, cutting vital credit flows through key arteries.

All of this preceded the populist deluge of 2016 and, indeed, contributed as policymakers myopically prioritised stability over social cohesion, ignoring the lessons of the past.

But globally, politicians are now fast realigning to shifting public moods. A year ago, to imagine a world where the major western leaders included Trump, the Brexit brigade and Marine Le Pen was the province of satire. Today, we are two-thirds there. Their ascendancy has shifted the political debate towards nativism in a hauntingly familiar nationalist narrative, as others follow suit.

Our new politics are not leftwing or rightwing, merely whether you are in this world or out of it. Even defenders of globalisation are falling into the same trap. By demonising those that voted against and not providing alternative options, they cling tighter to those that confirm and affirm their beliefs. That is still nativism of a different sort and still the politics of division, not unity.

This is Deglobalisation 2.0.

Monetary policies such as quantitative easing and its newborn sibling, fiscal easing, cannot change this dynamic. Absent structural change, their cumulative corrosive impact on savings and fillip to global debt ensure a limited runway and only inflame the rhetoric of disenfranchisement. Meanwhile, divorces are turning ugly as emotions override reason, viz the talk of Brexit fees and anti-dumping levies, the metaphorical Kristallnacht of populist victors like May and Trump as they struggle for coherence, and emerging divisions between central banks and politicians, to name but a few.

Democracy is fast turning to kakistocracy – government by the least qualified leaders. Globalisation is transmuting to nationalism. The effects are well documented in history – autarky, economic naivety, protectionism and a rush to grab what remains of the pie, only to trample it underfoot.

Me first always ends in me last. The world is still getting smaller, but just in our minds and horizons now, and thoughtless we risk becoming all the poorer for it.

Thursday, 1 December 2016

There is a plan: Brexit means good riddance to austerity

John Redwood in The Guardian

As we leave the EU, the UK can turn its back on the austerity policies that have been the hallmark of the euro area. My main argument against staying in the EU has been the poor economic record of the EU as a whole, and the eurozone in particular. The performance has got worse the more the EU has developed joint policies and central controls.

Housing gets £4bn boost to increase number of new homes

The UK public warmed to the idea of spending our own money on our own priorities in the referendum campaign. The main issue between leave and remain was the money. Remain tried to dismiss its importance by claiming there was in practice little money at stake, and disagreed strongly with any reference to the gross figure for UK contributions.

The public did not take away one particular figure from the debate, but did believe that we contributed substantial money that it would be useful to spend at home. Cancelling the contributions would also make an important reduction in our large balance of payments deficit, as every penny we send and do not get back swells the deficit, just as surely as if we bought another import.

During the campaign I released a draft post-Brexit budget, showing how we could scrap VAT on domestic fuel, tampons and green products, and boost spending substantially on the NHS.

The government will be able to choose what to do once we have stopped the payments. The autumn statement showed a saving of a net contribution of £11.6bn in 2019-20 once we are out of the EU, as well as additional domestic spending in place of spending in the UK by the EU currently.

I am glad the chancellor has also adopted more flexible rules for the budget deficit. There is no need to genuflect to the Maastricht debt and deficit criteria once we leave, nor to pretend that we are about to get our overall debt down to 60% of GDP, as is required by those rules. The UK economy needs further stimulus, as the autumn statement acknowledged. There are roads and railway lines to be built, new power stations to be added, more water storage, schools and hospitals to cater for the rising population.

The government is right to say the UK needs to invest more. We need to make new provision for all the additional people who have joined the country in recent years, and to improve the efficiency of our infrastructure. The country is well behind in meeting demand for train and road capacity, and in energy provision.

The UK also needs to make, grow and provide more for its own needs. Leaving the EU will enable the UK to undertake a major campaign for import substitution. When we have our own fishing policy we could move back to being net exporters, instead of being importers. The common fisheries policy means too much of our fish is taken by other member states, leaving us short for our own needs. Designing our own agriculture policy will mean we can put behind us the quotas and regulations that have held back UK output during our years in the EU. We can change our procurement rules, so that the government when spending taxpayers’ money can ensure more is bought from home suppliers.

Why do we have a balance of payments surplus with the rest of the world but a deficit with our EU neighbours?

The UK is embarking on a substantial expansion of housebuilding. Too many materials and components for our new homes are imported. The lower level of sterling provides an opportunity for the UK to put in more brick, block and tile capacity, to prefabricate and manufacture more of the components and systems a new home needs. If more of the home is fabricated off-site – as happens in Germany and Scandinavia – we reduce the impact of bad weather, of labour shortages and other inefficiencies on the building site. Industry by industry there are opportunities for suitable investment and entrepreneurial activity, to meet more of the UK’s own demands. This will be good for jobs, and better for the environment, when more is produced close to the place of consumption.

As we leave the EU, the UK can turn its back on the austerity policies that have been the hallmark of the euro area. My main argument against staying in the EU has been the poor economic record of the EU as a whole, and the eurozone in particular. The performance has got worse the more the EU has developed joint policies and central controls.

Housing gets £4bn boost to increase number of new homes

The UK public warmed to the idea of spending our own money on our own priorities in the referendum campaign. The main issue between leave and remain was the money. Remain tried to dismiss its importance by claiming there was in practice little money at stake, and disagreed strongly with any reference to the gross figure for UK contributions.

The public did not take away one particular figure from the debate, but did believe that we contributed substantial money that it would be useful to spend at home. Cancelling the contributions would also make an important reduction in our large balance of payments deficit, as every penny we send and do not get back swells the deficit, just as surely as if we bought another import.

During the campaign I released a draft post-Brexit budget, showing how we could scrap VAT on domestic fuel, tampons and green products, and boost spending substantially on the NHS.

The government will be able to choose what to do once we have stopped the payments. The autumn statement showed a saving of a net contribution of £11.6bn in 2019-20 once we are out of the EU, as well as additional domestic spending in place of spending in the UK by the EU currently.

I am glad the chancellor has also adopted more flexible rules for the budget deficit. There is no need to genuflect to the Maastricht debt and deficit criteria once we leave, nor to pretend that we are about to get our overall debt down to 60% of GDP, as is required by those rules. The UK economy needs further stimulus, as the autumn statement acknowledged. There are roads and railway lines to be built, new power stations to be added, more water storage, schools and hospitals to cater for the rising population.

The government is right to say the UK needs to invest more. We need to make new provision for all the additional people who have joined the country in recent years, and to improve the efficiency of our infrastructure. The country is well behind in meeting demand for train and road capacity, and in energy provision.

The UK also needs to make, grow and provide more for its own needs. Leaving the EU will enable the UK to undertake a major campaign for import substitution. When we have our own fishing policy we could move back to being net exporters, instead of being importers. The common fisheries policy means too much of our fish is taken by other member states, leaving us short for our own needs. Designing our own agriculture policy will mean we can put behind us the quotas and regulations that have held back UK output during our years in the EU. We can change our procurement rules, so that the government when spending taxpayers’ money can ensure more is bought from home suppliers.

Why do we have a balance of payments surplus with the rest of the world but a deficit with our EU neighbours?

The UK is embarking on a substantial expansion of housebuilding. Too many materials and components for our new homes are imported. The lower level of sterling provides an opportunity for the UK to put in more brick, block and tile capacity, to prefabricate and manufacture more of the components and systems a new home needs. If more of the home is fabricated off-site – as happens in Germany and Scandinavia – we reduce the impact of bad weather, of labour shortages and other inefficiencies on the building site. Industry by industry there are opportunities for suitable investment and entrepreneurial activity, to meet more of the UK’s own demands. This will be good for jobs, and better for the environment, when more is produced close to the place of consumption.

One of the great unanswered questions of our time in the EU is: why do we run a balance of payments surplus with the rest of the world but a deficit with our EU neighbours? Why has it been so large and so persistent? Part of the reason rests in the way the EU rules were organised.

Early liberalisation was designed to help the sectors the continent was best at, rather than the sectors where the UK had a relative advantage. The continental competitors soon outpaced us in their better areas, leading to UK factory closures and job losses in areas like shipbuilding steel production and cars in the early years of membership. The special designs of the common agricultural and fishing policies also led to larger import bills for us.

Leaving the EU has coincided, so far, with a fall in the value of the pound. The UK should now be very competitive. It is time for business to respond to the favourable levels of domestic demand, and to work with government to put in the extra capacity we need to meet more of our own requirements. Prosperity, not austerity, should be the watchword.

Early liberalisation was designed to help the sectors the continent was best at, rather than the sectors where the UK had a relative advantage. The continental competitors soon outpaced us in their better areas, leading to UK factory closures and job losses in areas like shipbuilding steel production and cars in the early years of membership. The special designs of the common agricultural and fishing policies also led to larger import bills for us.

Leaving the EU has coincided, so far, with a fall in the value of the pound. The UK should now be very competitive. It is time for business to respond to the favourable levels of domestic demand, and to work with government to put in the extra capacity we need to meet more of our own requirements. Prosperity, not austerity, should be the watchword.

Cricket: Why you need to master defence to score runs

Jon Hotten in Cricinfo

Technique is a servant, not a master. Take the example of Jonny Bairstow, and his successful comeback to the England Test side

Dropped from the Test side after a run of low scores, Jonny Bairstow worked out his technical flaws and became a prolific run scorer © Getty Images

Dropped from the Test side after a run of low scores, Jonny Bairstow worked out his technical flaws and became a prolific run scorer © Getty Images

Graham Gooch once said, "I don't coach batting, I coach run-scoring." In a sentence he defined the requirements of the game's highest levels: those who arrived there already knew how to bat; what they needed to know was how to prosper on the mean streets, where the pressure was greatest and where any and every weakness would be found and exploited.

It suggested, too, that technique is a servant rather than a master, a means to an end rather than the end itself. Ugly runs count the same as pretty ones; David Gower's and Shivnarine Chanderpaul's look just the same in the scorebook, if not the history book. And as Alastair Cook, Gooch's most famous pupil, has moved inexorably onto the list of the all-time top ten Test match run scorers, and Goochie himself got more than anyone else across all forms of cricket, he's probably on to something.

Like all good buzzwords, technique has been thrumming through Test series between England and India, and Australia and South Africa. There's nothing like a batting collapse to begin the self-evisceration. Speaking to the Guardian for a thoughtful examination of Australian concepts of batting written by Sam Perry, Ed Cowan said: "One of [our] biggest issues is the attitude of 'attack at all costs', which I think is defunct in Test cricket. The message feeds through that we've got to pick attacking cricketers and that you need to be an attacking cricketer to be picked."

In India, Haseeb Hameed is the new poster boy for doing it right, the "baby Boycott", a kid with arms like sticks who hits through the covers with all of the easy power of a natural ball-player. Ben Duckett and Gary Ballance, having got it wrong, well, how must it feel to be them, to keep touring knowing that your tour is over and that stretching ahead is exile, and in that exile there are hard truths to be faced, hard labour to be undertaken.

They will join a list of recent discards, from Alex Hales to Sam Robson, Nick Compton to Adam Lyth, James Vince to Ian Bell, who have various hopes of a recall somehow, someday.

In that, they can look to Jonny Bairstow, who knows the feeling. When he was dropped from the side he averaged 27. He was out for 18 months and went through what he called some "dark spots". In the summer of 2014 he missed six weeks of domestic cricket with a broken finger and afterwards his renaissance began.

Bairstow addressed a point of technique. He felt that he was crouching too low in his stance, which led to a rigid right elbow and back and made him lunge at the ball, a fault compounded by a low backlift that often had him playing shots well in front of his body. He began standing up straighter and holding his hands higher, the bat hovering almost baseball-style as he waited. He still waggled the bat, but it came at the ball from a steeper angle and because of that it arrived later, which meant the interception point was under his eyes, where he was perfectly balanced. He laid waste to county attacks and was recalled for the 2015 Ashes. In 2016 he has made 1355 runs, more than any wicketkeeper in a calendar year, at an average of 64.52.

"You got two options," he says of being dropped. "You either run and hide or you front up."

It wouldn't have happened without a technical change, but then the technical change would not have happened without the desire to improve, to escape that darkness. He had what seems like the right attitude to technique, that it existed to serve him, to help him score runs. If he wasn't scoring runs, then he needed to find out why.

Dean Jones, the former Australia batsman, has published a book called Dean Jones' Cricket Tips (The Things They Don't Teach You At The Academy), about the kind of small improvements players need to make to evolve from being good professional sportsmen to international stars. He analysed a typical Sachin Tendulkar century, which took 180 deliveries, and found that Tendulkar left or defended around 70% of them - about 126 deliveries.

It suggested that the ability to stay in remains a great batsman's primary quality. His array of of scoring strokes, however wide and thrilling, are restricted to one ball in three. What all players looking to score runs must be able to do is defend forward and back and leave the ball well. To score runs, you begin by knowing how to not score them too.

It's interesting that the most discussed technical flaws always apply to defensive technique. England's most improved players, Bairstow and Ben Stokes, have improved most in that area. The problems of Duckett and Ballance lie there. For all of modern batting's pyrotechnics, finding a way to stay in remains the key to it all, as Cook and Gooch continue to show.

Technique is a servant, not a master. Take the example of Jonny Bairstow, and his successful comeback to the England Test side

Dropped from the Test side after a run of low scores, Jonny Bairstow worked out his technical flaws and became a prolific run scorer © Getty Images

Dropped from the Test side after a run of low scores, Jonny Bairstow worked out his technical flaws and became a prolific run scorer © Getty ImagesGraham Gooch once said, "I don't coach batting, I coach run-scoring." In a sentence he defined the requirements of the game's highest levels: those who arrived there already knew how to bat; what they needed to know was how to prosper on the mean streets, where the pressure was greatest and where any and every weakness would be found and exploited.

It suggested, too, that technique is a servant rather than a master, a means to an end rather than the end itself. Ugly runs count the same as pretty ones; David Gower's and Shivnarine Chanderpaul's look just the same in the scorebook, if not the history book. And as Alastair Cook, Gooch's most famous pupil, has moved inexorably onto the list of the all-time top ten Test match run scorers, and Goochie himself got more than anyone else across all forms of cricket, he's probably on to something.

Like all good buzzwords, technique has been thrumming through Test series between England and India, and Australia and South Africa. There's nothing like a batting collapse to begin the self-evisceration. Speaking to the Guardian for a thoughtful examination of Australian concepts of batting written by Sam Perry, Ed Cowan said: "One of [our] biggest issues is the attitude of 'attack at all costs', which I think is defunct in Test cricket. The message feeds through that we've got to pick attacking cricketers and that you need to be an attacking cricketer to be picked."

In India, Haseeb Hameed is the new poster boy for doing it right, the "baby Boycott", a kid with arms like sticks who hits through the covers with all of the easy power of a natural ball-player. Ben Duckett and Gary Ballance, having got it wrong, well, how must it feel to be them, to keep touring knowing that your tour is over and that stretching ahead is exile, and in that exile there are hard truths to be faced, hard labour to be undertaken.

They will join a list of recent discards, from Alex Hales to Sam Robson, Nick Compton to Adam Lyth, James Vince to Ian Bell, who have various hopes of a recall somehow, someday.

In that, they can look to Jonny Bairstow, who knows the feeling. When he was dropped from the side he averaged 27. He was out for 18 months and went through what he called some "dark spots". In the summer of 2014 he missed six weeks of domestic cricket with a broken finger and afterwards his renaissance began.

Bairstow addressed a point of technique. He felt that he was crouching too low in his stance, which led to a rigid right elbow and back and made him lunge at the ball, a fault compounded by a low backlift that often had him playing shots well in front of his body. He began standing up straighter and holding his hands higher, the bat hovering almost baseball-style as he waited. He still waggled the bat, but it came at the ball from a steeper angle and because of that it arrived later, which meant the interception point was under his eyes, where he was perfectly balanced. He laid waste to county attacks and was recalled for the 2015 Ashes. In 2016 he has made 1355 runs, more than any wicketkeeper in a calendar year, at an average of 64.52.

"You got two options," he says of being dropped. "You either run and hide or you front up."

It wouldn't have happened without a technical change, but then the technical change would not have happened without the desire to improve, to escape that darkness. He had what seems like the right attitude to technique, that it existed to serve him, to help him score runs. If he wasn't scoring runs, then he needed to find out why.

Dean Jones, the former Australia batsman, has published a book called Dean Jones' Cricket Tips (The Things They Don't Teach You At The Academy), about the kind of small improvements players need to make to evolve from being good professional sportsmen to international stars. He analysed a typical Sachin Tendulkar century, which took 180 deliveries, and found that Tendulkar left or defended around 70% of them - about 126 deliveries.

It suggested that the ability to stay in remains a great batsman's primary quality. His array of of scoring strokes, however wide and thrilling, are restricted to one ball in three. What all players looking to score runs must be able to do is defend forward and back and leave the ball well. To score runs, you begin by knowing how to not score them too.

It's interesting that the most discussed technical flaws always apply to defensive technique. England's most improved players, Bairstow and Ben Stokes, have improved most in that area. The problems of Duckett and Ballance lie there. For all of modern batting's pyrotechnics, finding a way to stay in remains the key to it all, as Cook and Gooch continue to show.

Wednesday, 30 November 2016

Frightened by Donald Trump? You don’t know the half of it

George Monbiot in The Guardian

Yes, Donald Trump’s politics are incoherent. But those who surround him know just what they want, and his lack of clarity enhances their power. To understand what is coming, we need to understand who they are. I know all too well, because I have spent the past 15 years fighting them.

Over this time, I have watched as tobacco, coal, oil, chemicals and biotech companies have poured billions of dollars into an international misinformation machine composed of thinktanks, bloggers and fake citizens’ groups. Its purpose is to portray the interests of billionaires as the interests of the common people, to wage war against trade unions and beat down attempts to regulate business and tax the very rich. Now the people who helped run this machine are shaping the government.

I first encountered the machine when writing about climate change. The fury and loathing directed at climate scientists and campaigners seemed incomprehensible until I realised they were fake: the hatred had been paid for. The bloggers and institutes whipping up this anger were funded by oil and coal companies.

Among those I clashed with was Myron Ebell of the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI). The CEI calls itself a thinktank, but looks to me like a corporate lobbying group. It is not transparent about its funding, but we now know it has received $2m from ExxonMobil, more than $4m from a group called the Donors Trust (which represents various corporations and billionaires), $800,000 from groups set up by the tycoons Charles and David Koch, and substantial sums from coal, tobacco and pharmaceutical companies.

For years, Ebell and the CEI have attacked efforts to limit climate change, through lobbying, lawsuits and campaigns. An advertisement released by the institute had the punchline “Carbon dioxide: they call it pollution. We call it life.”

Former campaign manager Corey Lewandowski, like other members of Trump’s team, came from a group called Americans for Prosperity. Photograph: UPI/Barcroft Images

It has sought to eliminate funding for environmental education, lobbied against the Endangered Species Act, harried climate scientists and campaigned in favour of mountaintop removal by coal companies. In 2004, Ebell sent a memo to one of George W Bush’s staffers calling for the head of the Environmental Protection Agency to be sacked. Where is Ebell now? Oh – leading Trump’s transition team for the Environmental Protection Agency.

Charles and David Koch – who for years have funded extreme pro-corporate politics – might not have been enthusiasts for Trump’s candidacy, but their people were all over his campaign. Until June, Trump’s campaign manager was Corey Lewandowski, who like other members of Trump’s team came from a group called Americans for Prosperity (AFP).

This purports to be a grassroots campaign, but it was founded and funded by the Koch brothers. It set up the first Tea Party Facebook page and organised the first Tea Party events. With a budget of hundreds of millions of dollars, AFP has campaigned ferociously on issues that coincide with the Koch brothers’ commercial interests in oil, gas, minerals, timber and chemicals.

In Michigan, it helped force through the “right to work bill”, in pursuit of what AFP’s local director called “taking the unions out at the knees”. It has campaigned nationwide against action on climate change. It has poured hundreds of millions of dollars into unseating the politicians who won’t do its bidding and replacing them with those who will.

I could fill this newspaper with the names of Trump staffers who have emerged from such groups: people such as Doug Domenech, from the Texas Public Policy Foundation, funded among others by the Koch brothers, Exxon and the Donors Trust; Barry Bennett, whose Alliance for America’s Future (now called One Nation) refused to disclose its donors when challenged; and Thomas Pyle, president of the American Energy Alliance, funded by Exxon and others. This is to say nothing of Trump’s own crashing conflicts of interest. Trump promised to “drain the swamp” of the lobbyists and corporate stooges working in Washington. But it looks as if the only swamps he’ll drain will be real ones, as his team launches its war on the natural world.

Understandably, there has been plenty of coverage of the racists and white supremacists empowered by Trump’s victory. But, gruesome as they are, they’re peripheral to the policies his team will develop. It’s almost comforting, though, to focus on them, for at least we know who they are and what they stand for. By contrast, to penetrate the corporate misinformation machine is to enter a world of mirrors. Spend too long trying to understand it, and the hyporeality vortex will inflict serious damage on your state of mind.

Don’t imagine that other parts of the world are immune. Corporate-funded thinktanks and fake grassroots groups are now everywhere. The fake news we should be worried about is not stories invented by Macedonian teenagers about Hillary Clinton selling arms to Islamic State, but the constant feed of confected scares about unions, tax and regulation drummed up by groups that won’t reveal their interests.

The less transparent they are, the more airtime they receive. The organisation Transparify runs an annual survey of thinktanks. This year’s survey reveals that in the UK only four thinktanks – the Adam Smith Institute, Centre for Policy Studies, Institute of Economic Affairs and Policy Exchange – “still consider it acceptable to take money from hidden hands behind closed doors”. And these are the ones that are all over the media.

When the Institute of Economic Affairs, as it so often does, appears on the BBC to argue against regulating tobacco, shouldn’t we be told that it has been funded by tobacco companies since 1963? There’s a similar pattern in the US: the most vocal groups tend to be the most opaque.

As usual, the left and centre (myself included) are beating ourselves up about where we went wrong. There are plenty of answers, but one of them is that we have simply been outspent. Not by a little, but by orders of magnitude. A few billion dollars spent on persuasion buys you all the politics you want. Genuine campaigners, working in their free time, simply cannot match a professional network staffed by thousands of well-paid, unscrupulous people.

You cannot confront a power until you know what it is. Our first task in this struggle is to understand what we face. Only then can we work out what to do,

Yes, Donald Trump’s politics are incoherent. But those who surround him know just what they want, and his lack of clarity enhances their power. To understand what is coming, we need to understand who they are. I know all too well, because I have spent the past 15 years fighting them.

Over this time, I have watched as tobacco, coal, oil, chemicals and biotech companies have poured billions of dollars into an international misinformation machine composed of thinktanks, bloggers and fake citizens’ groups. Its purpose is to portray the interests of billionaires as the interests of the common people, to wage war against trade unions and beat down attempts to regulate business and tax the very rich. Now the people who helped run this machine are shaping the government.

I first encountered the machine when writing about climate change. The fury and loathing directed at climate scientists and campaigners seemed incomprehensible until I realised they were fake: the hatred had been paid for. The bloggers and institutes whipping up this anger were funded by oil and coal companies.

Among those I clashed with was Myron Ebell of the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI). The CEI calls itself a thinktank, but looks to me like a corporate lobbying group. It is not transparent about its funding, but we now know it has received $2m from ExxonMobil, more than $4m from a group called the Donors Trust (which represents various corporations and billionaires), $800,000 from groups set up by the tycoons Charles and David Koch, and substantial sums from coal, tobacco and pharmaceutical companies.

For years, Ebell and the CEI have attacked efforts to limit climate change, through lobbying, lawsuits and campaigns. An advertisement released by the institute had the punchline “Carbon dioxide: they call it pollution. We call it life.”

Former campaign manager Corey Lewandowski, like other members of Trump’s team, came from a group called Americans for Prosperity. Photograph: UPI/Barcroft Images

It has sought to eliminate funding for environmental education, lobbied against the Endangered Species Act, harried climate scientists and campaigned in favour of mountaintop removal by coal companies. In 2004, Ebell sent a memo to one of George W Bush’s staffers calling for the head of the Environmental Protection Agency to be sacked. Where is Ebell now? Oh – leading Trump’s transition team for the Environmental Protection Agency.

Charles and David Koch – who for years have funded extreme pro-corporate politics – might not have been enthusiasts for Trump’s candidacy, but their people were all over his campaign. Until June, Trump’s campaign manager was Corey Lewandowski, who like other members of Trump’s team came from a group called Americans for Prosperity (AFP).

This purports to be a grassroots campaign, but it was founded and funded by the Koch brothers. It set up the first Tea Party Facebook page and organised the first Tea Party events. With a budget of hundreds of millions of dollars, AFP has campaigned ferociously on issues that coincide with the Koch brothers’ commercial interests in oil, gas, minerals, timber and chemicals.

In Michigan, it helped force through the “right to work bill”, in pursuit of what AFP’s local director called “taking the unions out at the knees”. It has campaigned nationwide against action on climate change. It has poured hundreds of millions of dollars into unseating the politicians who won’t do its bidding and replacing them with those who will.

I could fill this newspaper with the names of Trump staffers who have emerged from such groups: people such as Doug Domenech, from the Texas Public Policy Foundation, funded among others by the Koch brothers, Exxon and the Donors Trust; Barry Bennett, whose Alliance for America’s Future (now called One Nation) refused to disclose its donors when challenged; and Thomas Pyle, president of the American Energy Alliance, funded by Exxon and others. This is to say nothing of Trump’s own crashing conflicts of interest. Trump promised to “drain the swamp” of the lobbyists and corporate stooges working in Washington. But it looks as if the only swamps he’ll drain will be real ones, as his team launches its war on the natural world.

Understandably, there has been plenty of coverage of the racists and white supremacists empowered by Trump’s victory. But, gruesome as they are, they’re peripheral to the policies his team will develop. It’s almost comforting, though, to focus on them, for at least we know who they are and what they stand for. By contrast, to penetrate the corporate misinformation machine is to enter a world of mirrors. Spend too long trying to understand it, and the hyporeality vortex will inflict serious damage on your state of mind.

Don’t imagine that other parts of the world are immune. Corporate-funded thinktanks and fake grassroots groups are now everywhere. The fake news we should be worried about is not stories invented by Macedonian teenagers about Hillary Clinton selling arms to Islamic State, but the constant feed of confected scares about unions, tax and regulation drummed up by groups that won’t reveal their interests.

The less transparent they are, the more airtime they receive. The organisation Transparify runs an annual survey of thinktanks. This year’s survey reveals that in the UK only four thinktanks – the Adam Smith Institute, Centre for Policy Studies, Institute of Economic Affairs and Policy Exchange – “still consider it acceptable to take money from hidden hands behind closed doors”. And these are the ones that are all over the media.

When the Institute of Economic Affairs, as it so often does, appears on the BBC to argue against regulating tobacco, shouldn’t we be told that it has been funded by tobacco companies since 1963? There’s a similar pattern in the US: the most vocal groups tend to be the most opaque.

As usual, the left and centre (myself included) are beating ourselves up about where we went wrong. There are plenty of answers, but one of them is that we have simply been outspent. Not by a little, but by orders of magnitude. A few billion dollars spent on persuasion buys you all the politics you want. Genuine campaigners, working in their free time, simply cannot match a professional network staffed by thousands of well-paid, unscrupulous people.

You cannot confront a power until you know what it is. Our first task in this struggle is to understand what we face. Only then can we work out what to do,

Tuesday, 29 November 2016

How Isis recruiters found fertile ground in Kerala

Michael Safi in The Guardian

The Keralan backwaters are a pretty network of lakes, rivers and canals stretching almost half the length of the state. Photograph: Oyster Opera Resort

Padanna in Kerala is the home town to at least six young men who are believed to have left to join the Islamic State Photograph: Sasi Kollikal for the Guardian

Residents of Kerala like to call their lush south Indian state, “God’s own country”. Hafizuddin Hakim disagreed.

The 23-year-old left his wife and family in June, telling them he was headed to Sri Lanka to pursue his Islamic studies. Around the same time, 16 others slipped out of his district, Kasargod, and another four from neighbouring Palakkad.

The next anyone heard from the missing 21 was an encrypted audio recording sent from an Afghan number. “We reached our destination,” it said. “There is no point in complaining to police ... We have no plans to return from the abode of Allah.”

The mass disappearance of the group, widely believed – but not confirmed– to have joined Islamic State, is one of a number of incidents this year that have raised fears that India, so far unscathed by the terrorist group, might be seeing increased activity.

India’s Muslim population, the third largest in the world, has so far contributed negligible numbers to Isis – fewer than 90 people, according to most estimates. “More have gone from Britain, even from the Maldives, than India,” says Vikram Sood, a former chief of India’s foreign spy agency.

But growing concern over the group’s influence was made official this month, when the US embassy in Delhi issued its first Isis-related warning, of an “increased threat to places in India frequented by Westerners, such as religious sites, markets and festival venues”.

However, it is not India’s harsh, dry north, nor Kashmir, the site of a burning Islamic insurgency, where Isis has found most appeal. The group’s unlikely recruiting ground is Kerala, one of India’s wealthiest, most diverse and best-educated states.

Minarets and palm trees intersperse the skyline along Kerala’s Malabar coast, a verdant region of paddies and waterways that weave between villages like veins.

Padanna, in the north of the state, is a typical backwater town: orderly, lined with oversized houses, and made rich by remittances from its share of the nearly 2.5m Keralites who work in the Arab gulf.

It is also from where a dozen people, including Hakim, vanished in June. “He was a carefree, easy-going boy,” recalls his uncle, Abdul Rahim. “He used to indulge in all kinds of activities, smoking, drinking. He was not that religious.”

Hakim had worked in the United Arab Emirates in his late teens, returning to Padanna two years ago. A little aimless, he fell in with a new crowd, centred around an employee of the local Peace International School, an education franchise that adheres to a hardline Salafi Muslim ideology (but which has denied any involvement in the group’s disappearance).

Residents of Kerala like to call their lush south Indian state, “God’s own country”. Hafizuddin Hakim disagreed.

The 23-year-old left his wife and family in June, telling them he was headed to Sri Lanka to pursue his Islamic studies. Around the same time, 16 others slipped out of his district, Kasargod, and another four from neighbouring Palakkad.

The next anyone heard from the missing 21 was an encrypted audio recording sent from an Afghan number. “We reached our destination,” it said. “There is no point in complaining to police ... We have no plans to return from the abode of Allah.”

The mass disappearance of the group, widely believed – but not confirmed– to have joined Islamic State, is one of a number of incidents this year that have raised fears that India, so far unscathed by the terrorist group, might be seeing increased activity.

India’s Muslim population, the third largest in the world, has so far contributed negligible numbers to Isis – fewer than 90 people, according to most estimates. “More have gone from Britain, even from the Maldives, than India,” says Vikram Sood, a former chief of India’s foreign spy agency.

But growing concern over the group’s influence was made official this month, when the US embassy in Delhi issued its first Isis-related warning, of an “increased threat to places in India frequented by Westerners, such as religious sites, markets and festival venues”.

However, it is not India’s harsh, dry north, nor Kashmir, the site of a burning Islamic insurgency, where Isis has found most appeal. The group’s unlikely recruiting ground is Kerala, one of India’s wealthiest, most diverse and best-educated states.

Minarets and palm trees intersperse the skyline along Kerala’s Malabar coast, a verdant region of paddies and waterways that weave between villages like veins.

Padanna, in the north of the state, is a typical backwater town: orderly, lined with oversized houses, and made rich by remittances from its share of the nearly 2.5m Keralites who work in the Arab gulf.

It is also from where a dozen people, including Hakim, vanished in June. “He was a carefree, easy-going boy,” recalls his uncle, Abdul Rahim. “He used to indulge in all kinds of activities, smoking, drinking. He was not that religious.”

Hakim had worked in the United Arab Emirates in his late teens, returning to Padanna two years ago. A little aimless, he fell in with a new crowd, centred around an employee of the local Peace International School, an education franchise that adheres to a hardline Salafi Muslim ideology (but which has denied any involvement in the group’s disappearance).

The Keralan backwaters are a pretty network of lakes, rivers and canals stretching almost half the length of the state. Photograph: Oyster Opera Resort

“All of a sudden he became a recluse,” Rahim says. He grew a wispy beard, cut the TV cable to his home and one day, stopped driving his car. “He said it was taken on loan, and a loan was anti-Islam.”

Salafism is not new to southern India, but an influx of Saudi Arabian money in the past decades – partly detailed in Saudi diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks – has produced a harder-edged Islam in the region, says Ashraf Kaddakal, a professor at the University of Kerala.

“It is a very narrow, very rigid, very reactionary kind of ideology,” he says. “And it has attracted many youngsters, especially students.

“These youngsters have detached from their [orthodox Sunni] leaders and started following the online Islam, the preaching and sermons of these Saudi and other Salafi scholars,” he says. “They indoctrinated many through these internet preachings.”

Kadakkal himself has tried to counsel dozens of young people, whose parents fear their children’s increasingly rigid faith. “My counselling has been a total failure”, he admits. “They blindly follow their masters. They get their fatwas from the internet.”

Whatever threat Isis poses to India is fundamentally different, and probably less pressing, than that which most occupies the minds of Indian security officials.

“For us the major fear is from groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba or Jaish-e-Mohammed,” says Sood, the former intelligence chief. “That is where the real, organised, state-sponsored threat lies.”

In contrast, those arrested so far on suspicion of Isis links or sympathies, numbering 68 people, have largely been self-starters, operating in small, unskilled networks.

“And they were almost all well-short of coming close to actually carrying out anything resembling a lethal operation,” says Praveen Swami, an author and journalist who specialises in strategic issues.

Still, the militant group has explicitly tried to ignite fervour among Indians. Its propaganda wing released a video in May featuring interviews with Indian recruits, including members of an existing jihadi group, the Indian Mujahideen, that pledged allegiance to Isis in 2014.

According to a National Intelligence Agency charge-sheet issued against 16 alleged extremists in July, authorities also believe Shafi Armar, a notorious Indian Mujahideen member believed to be in Syria, has been actively trying to groom recruits back home.

As well, Subahani Haja Moideen, one of six members of an alleged extremist cell arrested in northern Kerala in October, is believed to have actually returned from fighting with Isis in Iraq, where he reportedly met with some of the alleged organisers of the Paris terror attacks, according to Indian news agencies.

On the numbers, overall – and like al-Qaida before it – the group has so far failed to make deep roots in India.

Kadakkal suggests India’s idiosyncratic religious culture just doesn’t blend well with Isis’ highly orthodox worldview. “Indian soil is not right for this kind of extremism,” he says.

Sood agrees: “There is a lot of laissez faire in India, much more than in the more ordered societies of the modern world. We let things be, and that’s terrible when it comes to driving, but otherwise ... it has upsides.”

But the fault-line between Hindus and Muslim in India is a deep one, and the symbolic power of a successful attack could far outweigh any toll of casualties.

“I guess that is the real fear,” Swami says. “If even this small Isis thing succeeds in carrying out large acts of violence, the political and knock-on consequences could create serious trouble.”

Salafism is not new to southern India, but an influx of Saudi Arabian money in the past decades – partly detailed in Saudi diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks – has produced a harder-edged Islam in the region, says Ashraf Kaddakal, a professor at the University of Kerala.

“It is a very narrow, very rigid, very reactionary kind of ideology,” he says. “And it has attracted many youngsters, especially students.

“These youngsters have detached from their [orthodox Sunni] leaders and started following the online Islam, the preaching and sermons of these Saudi and other Salafi scholars,” he says. “They indoctrinated many through these internet preachings.”

Kadakkal himself has tried to counsel dozens of young people, whose parents fear their children’s increasingly rigid faith. “My counselling has been a total failure”, he admits. “They blindly follow their masters. They get their fatwas from the internet.”

Whatever threat Isis poses to India is fundamentally different, and probably less pressing, than that which most occupies the minds of Indian security officials.

“For us the major fear is from groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba or Jaish-e-Mohammed,” says Sood, the former intelligence chief. “That is where the real, organised, state-sponsored threat lies.”

In contrast, those arrested so far on suspicion of Isis links or sympathies, numbering 68 people, have largely been self-starters, operating in small, unskilled networks.

“And they were almost all well-short of coming close to actually carrying out anything resembling a lethal operation,” says Praveen Swami, an author and journalist who specialises in strategic issues.

Still, the militant group has explicitly tried to ignite fervour among Indians. Its propaganda wing released a video in May featuring interviews with Indian recruits, including members of an existing jihadi group, the Indian Mujahideen, that pledged allegiance to Isis in 2014.

According to a National Intelligence Agency charge-sheet issued against 16 alleged extremists in July, authorities also believe Shafi Armar, a notorious Indian Mujahideen member believed to be in Syria, has been actively trying to groom recruits back home.

As well, Subahani Haja Moideen, one of six members of an alleged extremist cell arrested in northern Kerala in October, is believed to have actually returned from fighting with Isis in Iraq, where he reportedly met with some of the alleged organisers of the Paris terror attacks, according to Indian news agencies.

On the numbers, overall – and like al-Qaida before it – the group has so far failed to make deep roots in India.

Kadakkal suggests India’s idiosyncratic religious culture just doesn’t blend well with Isis’ highly orthodox worldview. “Indian soil is not right for this kind of extremism,” he says.

Sood agrees: “There is a lot of laissez faire in India, much more than in the more ordered societies of the modern world. We let things be, and that’s terrible when it comes to driving, but otherwise ... it has upsides.”

But the fault-line between Hindus and Muslim in India is a deep one, and the symbolic power of a successful attack could far outweigh any toll of casualties.

“I guess that is the real fear,” Swami says. “If even this small Isis thing succeeds in carrying out large acts of violence, the political and knock-on consequences could create serious trouble.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)