President Trump was an accident waiting to happen. The US had entered a zone of fragility: there were too many inequalities, grievances and accompanying disillusion in a system felt not to work .

A chief reason for that economic and social fragility was the behaviour of the American financial system. It is still astounding how close to disaster high finance brought the US and global economy in 2008. It provoked a vast bailout, and the recovery that followed has been one of the most anaemic sort, during which the wages of average Americans have scarcely grown.

The hangover of debt and legacy of banks trying to rebuild their shattered balance sheets has held the economy back. Meanwhile, some of the weak links in the system, like the sheer scale and opacity of the derivative markets, plus business models riddled with conflicts of interest, have remained unaddressed. Fortunes are still being made and very few have paid the price for cataclysmic mistakes.

On the campaign trail, Trump unfailingly tarred Clinton as compromised by, and enmeshed with, Wall Street and its mega banks. Goldman Sachs had “total control” of her; she was in thrall to a “global power structure that is responsible for the economic decisions that have robbed our working class, stripped our country of its wealth and put that money into the pockets of a handful of large corporations and political entities”.

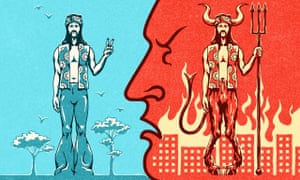

Trump would drain the swamp, he claimed, and reinstate a “21st-century” version of the law separating main street banking from Wall Street – Roosevelt’s Glass-Steagall Act – which was scrapped by President Bill Clinton, in one of his worst decisions. Trump would throw the money men out of the temple, he said. He would reshape finance for the “little guy”. His audiences roared him on.

But, in office, Trump has proved to be a great deal friendlier to the titans of Wall Street and their interests than he suggested he would be as a candidate, although a close reading of his speeches foretells some of what is now happening. Far from draining the swamp, he is opening the sluicegates; the money men are not so much being hurled out as in full occupation of the economic citadel.

Goldman Sachs’ number two, Gary Cohn, is to be Trump’s chief economic adviser; his Treasury secretary, Steve Mnuchin, was 20 years at Goldman Sachs before running OneWest Bank, which made a fortune by improperly foreclosing on mortgages in ethnic minority communities after the financial crisis. These are not men on the side of the little guy: Cohn has promised to attack “all aspects of Dodd-Frank”, the partially effective regulatory framework that Obama laboriously passed into law in 2010, in the teeth of Republican and Wall Street opposition.

What we know from the financial crisis is that the banking system has become a highly interdependent network in which contagion spreads in hours – it is only as strong as its weakest link. Yet Trump, in thrall to some of the most demonic figures in American finance, last week demanded a 120-day review of all the US’s financial regulations to tame their alleged excesses.

His intent is clear. He has Dodd-Frank in his sights, a “disaster” on which he aims to do “a big number”. There is only one end: to regulate the links in the financial network so they have even less oversight than they do now. And, if things go wrong, Trump will have no hesitation in writing whatever cheques that have to be written to bail out the banks again, just as he backed the bailouts in 2008/9. It is careless, don’t-give-a-damn insouciance on an epic scale.

It seems that a 21st-century version of Glass-Steagall, the core building block in the wholesale reconstruction of the US financial system in the wake of the Depression, was code for doing the exact opposite. Dodd-Frank certainly has weaknesses – in many respects, it does not go far enough and many of its recommendations are yet to be enacted – but it has made US banking immeasurably safer.

Former Goldman Sachs banker Gary Cohn, left, now Trump’s senior economic adviser, flanks the president during a meeting with business leaders in the White House. Photograph: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

The banks now hold a third more capital than they did 10 years ago. They are forbidden from trading in securities on their own account. Thirty-four of them, described as “systemically important financial institutions”, are kept under especially close watch, as key elements in the network. The newly established Consumer Financial Protection Bureau tries to ensure customers are dealt with honestly.

You might think after the extraordinary fraud at Wells Fargo last autumn – bank employees opening millions of phantom accounts and credit cards in customers’ names – that a president on the side of the little guy would at the very least not want to weaken American financial regulation. Rather, Trump is in sympathy with the bankers, horrified at the scale of fines they are now paying – Wells Fargo paid a cool $185m. He is also scandalised that holding so much buffer capital and not being able to trade in securities is damaging the bankers’ personal remuneration.

Dodd-Frank has been under fire since its inception, but then Republicans hated the New Deal too. Roosevelt, like Obama, was a hate figure whose every work had to be undone. Both men represented challenges to an idea of America as offering limitless freedom, not least to billionaires. The accompanying social distress is a price worth paying for such freedom – or so the thinking goes.

Billionaire Trump was right in one respect: Hillary Clinton was profoundly compromised by her relationship with Goldman Sachs, pocketing $675,000 for a mere three private speeches, in which she did voice sympathetic concerns about Dodd-Frank for allegedly making banks more cautious in their lending. She was, and is, indisputably a member of a global elite that cannot escape responsibility for the emergence of so many blighted lives.

But, beyond that, Trump is a phony. His economic programme is no more than Reaganomics on speed run by a group of opportunists and self-interested chancers. In the short run, there will be a Trump upswing triggered by the prospect of careless deregulation, unaffordable cuts in corporate tax and lots of infrastructure spending.

How long it will last, and whether it will be a trade war or a financial crisis that will bring it to an end, is anybody’s guess. But we have now had a glimpse of a darker Trump, the hypocrite for whom the little guy is but a pawn to serve his own delusional ambitions. Pity the US. And pity Brexit Britain, forced to bend the knee to such a man and such a president.

You might think after the extraordinary fraud at Wells Fargo last autumn – bank employees opening millions of phantom accounts and credit cards in customers’ names – that a president on the side of the little guy would at the very least not want to weaken American financial regulation. Rather, Trump is in sympathy with the bankers, horrified at the scale of fines they are now paying – Wells Fargo paid a cool $185m. He is also scandalised that holding so much buffer capital and not being able to trade in securities is damaging the bankers’ personal remuneration.

Dodd-Frank has been under fire since its inception, but then Republicans hated the New Deal too. Roosevelt, like Obama, was a hate figure whose every work had to be undone. Both men represented challenges to an idea of America as offering limitless freedom, not least to billionaires. The accompanying social distress is a price worth paying for such freedom – or so the thinking goes.

Billionaire Trump was right in one respect: Hillary Clinton was profoundly compromised by her relationship with Goldman Sachs, pocketing $675,000 for a mere three private speeches, in which she did voice sympathetic concerns about Dodd-Frank for allegedly making banks more cautious in their lending. She was, and is, indisputably a member of a global elite that cannot escape responsibility for the emergence of so many blighted lives.

But, beyond that, Trump is a phony. His economic programme is no more than Reaganomics on speed run by a group of opportunists and self-interested chancers. In the short run, there will be a Trump upswing triggered by the prospect of careless deregulation, unaffordable cuts in corporate tax and lots of infrastructure spending.

How long it will last, and whether it will be a trade war or a financial crisis that will bring it to an end, is anybody’s guess. But we have now had a glimpse of a darker Trump, the hypocrite for whom the little guy is but a pawn to serve his own delusional ambitions. Pity the US. And pity Brexit Britain, forced to bend the knee to such a man and such a president.