Ramachandra Guha in The Hindustan Times

Back in 2005, a knowledgeable Gujarati journalist wrote of how ‘Narendra Modi thinks a detergent named development will wash away the memory of 2002’. While focusing on new infrastructure and industrial projects in his state, the then chief minister of Gujarat launched what the journalist called ‘a massive self-publicity drive’, publishing calendars, booklets and posters where his own photograph appeared prominently alongside words and statistics speaking of Gujarat’s achievements under his leadership. ‘Modi has made sure that in Gujarat no one can escape noticing him,’ remarked the journalist.

Since May 2014, this self-publicity drive has been extended to the nation as a whole. In fact, the process began before the general elections, when, through social media and his speeches, Narendra Modi successfully projected himself as the sole and singular alternative to a (visibly) corrupt UPA regime. The BJP, a party previously opposed to ‘vyakti puja’, succumbed to the power of Modi’s personality. Since his swearing-in as Prime Minister, the government has done what the party did before it: totally subordinated itself to the will, and occasionally the whim, of a single individual.

Hero-worship is not uncommon in India. Indeed, we tend to excessively venerate high achievers in many fields. Consider the extraordinarily large and devoted fan following of Sachin Tendulkar and Lata Mangeshkar. These fans see their icons as flawless in a way fans in other countries do not. In America, Bob Dylan has many admirers but also more than a few critics. The same is true of the British tennis player Andy Murray. But in public discourse in India, criticism of Sachin and Lata is extremely rare. When offered, it tends to be met with vituperative abuse, not by rational or reasoned rebuttal.

The hero-worship of sportspeople is merely silly. But the hero-worship of politicians is inimical to democracy. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu were epicentres of progressive social reform, whose activists promoted caste and gender equality, rational thinking, and individual rights. Yet in more recent years, Maharashra has seen the cult of Bal Thackeray, Tamil Nadu the cult of J Jayalalithaa. In each case, the power of the State was (in Jayalalithaa’s case still is) put in service of this personality cult, with harassment and intimidation of critics being common.

However, at a nation-wide level the cult of Narendra Modi has had only one predecessor — that of Indira Gandhi. Thus now, as then, ruling party politicians demand that citizens see the Prime Minister as embodying not just the party or the government, but the nation itself. Millions of devotees on social media (as well as quite a few journalists) have succumbed to the most extreme form of hero-worship. More worryingly, one senior cabinet minister has called Narendra Modi a Messiah. A chief minister has insinuated that anyone who criticises the Prime Minister’s policies is anti-national. Meanwhile, as in Indira Gandhi’s time, the government’s publicity wing, as well as AIR and Doordarshan, works overtime to broadcast the Prime Minister’s image and achievements.

While viewing the promotion of this cult of Narendra Modi, I have been reminded of two texts by long-dead thinker-politicians, both (sadly) still relevant. The first is an essay published by Jawaharlal Nehru in 1937 under the pen-name of ‘Chanakya’. Here Nehru, referring to himself in the third person (as Modi often does now), remarked: ‘Jawaharlal cannot become a fascist. Yet he has all the makings of a dictator in him — a vast popularity, a strong will directed to a well-defined purpose, energy, pride, organisational capacity, ability, hardness, and, with all his love of the crowd, an intolerance of others and a certain contempt for the weak and the inefficient.’

Nehru was here issuing a warning to himself. Twelve years later, in his remarkable last speech to the Constituent Assembly, BR Ambedkar issued a warning to all Indians, when, invoking John Stuart Mill, he asked them not ‘to lay their liberties at the feet of even a great man, or to trust him with powers which enable him to subvert their institutions’. There was ‘nothing wrong’, said Ambedkar, ‘in being grateful to great men who have rendered life-long services to the country. But there are limits to gratefulness.’ He worried that in India, ‘Bhakti or what may be called the path of devotion or hero-worship, plays a part in its politics unequalled in magnitude by the part it plays in the politics of any other country in the world. Bhakti in religion may be a road to the salvation of the soul. But in politics, Bhakti or hero-worship is a sure road to degradation and to eventual dictatorship.’

These remarks uncannily anticipated the cult of Indira Gandhi and the Emergency. As I have written in these columns before, Indian democracy is now too robust to be destroyed by a single individual. But it can still be severely damaged. That is why this personality cult of Narendra Modi must be challenged (and checked) before it goes much further.

Later this week we shall observe the 60th anniversary of BR Ambedkar’s death. Some well-meaning (and brave) member of the Prime Minister’s inner circle should bring Ambedkar’s speech of 1949 to his attention. And perhaps Nehru’s pseudonymous article of 1937 too.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 4 December 2016

It's too late for globalisation – Kakistocracy is in fashion

Bob Swarup in The Guardian

The world is getting smaller. That is the unbidden meme of our generation, thanks to the juggernaut of growth unleashed by an outpouring of global bodies, free trade agreements, technology and international capital. Every business and person now has a global reach and audience.

Today’s paradigm is globalisation and free trade is its evangelical mantra.

But this narrative has become worn and no longer fits the facts. In recent months, there has been a backlash, accompanied by emotive talk about the reversal of globalisation and the battle for society’s future. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development used its latest health check on the global economy to warn of the costs of protectionism.

The hand-wringing is half a decade too late, because globalisation is already dead and we are already some miles into the journey back.

Donald Trump and Theresa May are not flagbearers in the distance, they are catapults battering at the walls. Trump’s stated intent to pull the US out of the TPP on his first day in office underlines the new reality we inhabit, as does the European Union’s recent troubles closing a trade agreement with Canada thanks to Wallonia’s obstinence.

Today, we have a new meme – deglobalisation – as people turn their backs on an interconnected world economy and societies turn iconoclastic.

It is not for the first time.

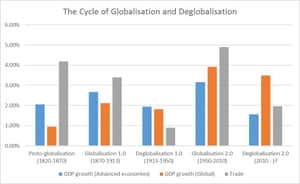

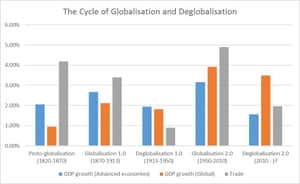

Globalisation may be defined as when trade across nations is growing faster than GDP. People interact more, transact more and create more wealth. Deglobalisation is the alternate state where trade grows less than GDP. Countries focus inwards, trade declines as a proportion of GDP and growth shrinks. A clear cycle of the two emerges over history.

Phases of globalisation and deglobalisation over the last two centuries. Illustration: Maddison, World Bank, Max Roser, CPB Netherlands, Camdor Global

Proto-globalisation (1820-1870): Rapid global trade growth, thanks to the Industrial Revolution and the spread of European colonial rule

Globalisation 1.0 (1870-1913): Empire building became the norm. Rapid advancements in transport and communications grew trade. But rapid change also meant volatile bouts of economic obsolescence and crisis

Deglobalisation 1.0 (1913-1950): Limited growth, unequal outcomes and a huge debt overhang from previous decades stoked economic nationalism and protectionism. Trade fell and a collective failure to tackle deeper structural issues led to the 1930s

Globalisation 2.0 (1950-2010): Since then, we have been on a tearaway expansion with unparalleled growth of both global trade and GDP

Deglobalisation 2.0 (2010-?): The last financial crisis focused policymaker attention inwards and crystallised the growing sense of social disenfranchisement. A toxic mix of suppressed wages, rocketing debt and political myopia have largely destroyed the allure of globalisation.

This is more than a sense of ennui. Global trade today is not slowing down but has plateaued – hardly a barometer of rude global health. After their peak in January 2015, global exports fell -1.6% by the end of August 2016. The blame lies not with commodity price falls, but shifts in trade policy. Protectionism is en vogue. Restrictive trade measures have outstripped liberalising measures three to one this year and increased by almost five times since 2009, as policymakers try to circumvent the WTO. Meanwhile, the deleveraging of banking balance sheets over recent years has hit global lending, as banks retreat from peripheral to core domestic activities, cutting vital credit flows through key arteries.

All of this preceded the populist deluge of 2016 and, indeed, contributed as policymakers myopically prioritised stability over social cohesion, ignoring the lessons of the past.

But globally, politicians are now fast realigning to shifting public moods. A year ago, to imagine a world where the major western leaders included Trump, the Brexit brigade and Marine Le Pen was the province of satire. Today, we are two-thirds there. Their ascendancy has shifted the political debate towards nativism in a hauntingly familiar nationalist narrative, as others follow suit.

Our new politics are not leftwing or rightwing, merely whether you are in this world or out of it. Even defenders of globalisation are falling into the same trap. By demonising those that voted against and not providing alternative options, they cling tighter to those that confirm and affirm their beliefs. That is still nativism of a different sort and still the politics of division, not unity.

This is Deglobalisation 2.0.

Monetary policies such as quantitative easing and its newborn sibling, fiscal easing, cannot change this dynamic. Absent structural change, their cumulative corrosive impact on savings and fillip to global debt ensure a limited runway and only inflame the rhetoric of disenfranchisement. Meanwhile, divorces are turning ugly as emotions override reason, viz the talk of Brexit fees and anti-dumping levies, the metaphorical Kristallnacht of populist victors like May and Trump as they struggle for coherence, and emerging divisions between central banks and politicians, to name but a few.

Democracy is fast turning to kakistocracy – government by the least qualified leaders. Globalisation is transmuting to nationalism. The effects are well documented in history – autarky, economic naivety, protectionism and a rush to grab what remains of the pie, only to trample it underfoot.

Me first always ends in me last. The world is still getting smaller, but just in our minds and horizons now, and thoughtless we risk becoming all the poorer for it.

The world is getting smaller. That is the unbidden meme of our generation, thanks to the juggernaut of growth unleashed by an outpouring of global bodies, free trade agreements, technology and international capital. Every business and person now has a global reach and audience.

Today’s paradigm is globalisation and free trade is its evangelical mantra.

But this narrative has become worn and no longer fits the facts. In recent months, there has been a backlash, accompanied by emotive talk about the reversal of globalisation and the battle for society’s future. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development used its latest health check on the global economy to warn of the costs of protectionism.

The hand-wringing is half a decade too late, because globalisation is already dead and we are already some miles into the journey back.

Donald Trump and Theresa May are not flagbearers in the distance, they are catapults battering at the walls. Trump’s stated intent to pull the US out of the TPP on his first day in office underlines the new reality we inhabit, as does the European Union’s recent troubles closing a trade agreement with Canada thanks to Wallonia’s obstinence.

Today, we have a new meme – deglobalisation – as people turn their backs on an interconnected world economy and societies turn iconoclastic.

It is not for the first time.

Globalisation may be defined as when trade across nations is growing faster than GDP. People interact more, transact more and create more wealth. Deglobalisation is the alternate state where trade grows less than GDP. Countries focus inwards, trade declines as a proportion of GDP and growth shrinks. A clear cycle of the two emerges over history.

Phases of globalisation and deglobalisation over the last two centuries. Illustration: Maddison, World Bank, Max Roser, CPB Netherlands, Camdor Global

Proto-globalisation (1820-1870): Rapid global trade growth, thanks to the Industrial Revolution and the spread of European colonial rule

Globalisation 1.0 (1870-1913): Empire building became the norm. Rapid advancements in transport and communications grew trade. But rapid change also meant volatile bouts of economic obsolescence and crisis

Deglobalisation 1.0 (1913-1950): Limited growth, unequal outcomes and a huge debt overhang from previous decades stoked economic nationalism and protectionism. Trade fell and a collective failure to tackle deeper structural issues led to the 1930s

Globalisation 2.0 (1950-2010): Since then, we have been on a tearaway expansion with unparalleled growth of both global trade and GDP

Deglobalisation 2.0 (2010-?): The last financial crisis focused policymaker attention inwards and crystallised the growing sense of social disenfranchisement. A toxic mix of suppressed wages, rocketing debt and political myopia have largely destroyed the allure of globalisation.

This is more than a sense of ennui. Global trade today is not slowing down but has plateaued – hardly a barometer of rude global health. After their peak in January 2015, global exports fell -1.6% by the end of August 2016. The blame lies not with commodity price falls, but shifts in trade policy. Protectionism is en vogue. Restrictive trade measures have outstripped liberalising measures three to one this year and increased by almost five times since 2009, as policymakers try to circumvent the WTO. Meanwhile, the deleveraging of banking balance sheets over recent years has hit global lending, as banks retreat from peripheral to core domestic activities, cutting vital credit flows through key arteries.

All of this preceded the populist deluge of 2016 and, indeed, contributed as policymakers myopically prioritised stability over social cohesion, ignoring the lessons of the past.

But globally, politicians are now fast realigning to shifting public moods. A year ago, to imagine a world where the major western leaders included Trump, the Brexit brigade and Marine Le Pen was the province of satire. Today, we are two-thirds there. Their ascendancy has shifted the political debate towards nativism in a hauntingly familiar nationalist narrative, as others follow suit.

Our new politics are not leftwing or rightwing, merely whether you are in this world or out of it. Even defenders of globalisation are falling into the same trap. By demonising those that voted against and not providing alternative options, they cling tighter to those that confirm and affirm their beliefs. That is still nativism of a different sort and still the politics of division, not unity.

This is Deglobalisation 2.0.

Monetary policies such as quantitative easing and its newborn sibling, fiscal easing, cannot change this dynamic. Absent structural change, their cumulative corrosive impact on savings and fillip to global debt ensure a limited runway and only inflame the rhetoric of disenfranchisement. Meanwhile, divorces are turning ugly as emotions override reason, viz the talk of Brexit fees and anti-dumping levies, the metaphorical Kristallnacht of populist victors like May and Trump as they struggle for coherence, and emerging divisions between central banks and politicians, to name but a few.

Democracy is fast turning to kakistocracy – government by the least qualified leaders. Globalisation is transmuting to nationalism. The effects are well documented in history – autarky, economic naivety, protectionism and a rush to grab what remains of the pie, only to trample it underfoot.

Me first always ends in me last. The world is still getting smaller, but just in our minds and horizons now, and thoughtless we risk becoming all the poorer for it.

Thursday, 1 December 2016

There is a plan: Brexit means good riddance to austerity

John Redwood in The Guardian

As we leave the EU, the UK can turn its back on the austerity policies that have been the hallmark of the euro area. My main argument against staying in the EU has been the poor economic record of the EU as a whole, and the eurozone in particular. The performance has got worse the more the EU has developed joint policies and central controls.

Housing gets £4bn boost to increase number of new homes

The UK public warmed to the idea of spending our own money on our own priorities in the referendum campaign. The main issue between leave and remain was the money. Remain tried to dismiss its importance by claiming there was in practice little money at stake, and disagreed strongly with any reference to the gross figure for UK contributions.

The public did not take away one particular figure from the debate, but did believe that we contributed substantial money that it would be useful to spend at home. Cancelling the contributions would also make an important reduction in our large balance of payments deficit, as every penny we send and do not get back swells the deficit, just as surely as if we bought another import.

During the campaign I released a draft post-Brexit budget, showing how we could scrap VAT on domestic fuel, tampons and green products, and boost spending substantially on the NHS.

The government will be able to choose what to do once we have stopped the payments. The autumn statement showed a saving of a net contribution of £11.6bn in 2019-20 once we are out of the EU, as well as additional domestic spending in place of spending in the UK by the EU currently.

I am glad the chancellor has also adopted more flexible rules for the budget deficit. There is no need to genuflect to the Maastricht debt and deficit criteria once we leave, nor to pretend that we are about to get our overall debt down to 60% of GDP, as is required by those rules. The UK economy needs further stimulus, as the autumn statement acknowledged. There are roads and railway lines to be built, new power stations to be added, more water storage, schools and hospitals to cater for the rising population.

The government is right to say the UK needs to invest more. We need to make new provision for all the additional people who have joined the country in recent years, and to improve the efficiency of our infrastructure. The country is well behind in meeting demand for train and road capacity, and in energy provision.

The UK also needs to make, grow and provide more for its own needs. Leaving the EU will enable the UK to undertake a major campaign for import substitution. When we have our own fishing policy we could move back to being net exporters, instead of being importers. The common fisheries policy means too much of our fish is taken by other member states, leaving us short for our own needs. Designing our own agriculture policy will mean we can put behind us the quotas and regulations that have held back UK output during our years in the EU. We can change our procurement rules, so that the government when spending taxpayers’ money can ensure more is bought from home suppliers.

Why do we have a balance of payments surplus with the rest of the world but a deficit with our EU neighbours?

The UK is embarking on a substantial expansion of housebuilding. Too many materials and components for our new homes are imported. The lower level of sterling provides an opportunity for the UK to put in more brick, block and tile capacity, to prefabricate and manufacture more of the components and systems a new home needs. If more of the home is fabricated off-site – as happens in Germany and Scandinavia – we reduce the impact of bad weather, of labour shortages and other inefficiencies on the building site. Industry by industry there are opportunities for suitable investment and entrepreneurial activity, to meet more of the UK’s own demands. This will be good for jobs, and better for the environment, when more is produced close to the place of consumption.

As we leave the EU, the UK can turn its back on the austerity policies that have been the hallmark of the euro area. My main argument against staying in the EU has been the poor economic record of the EU as a whole, and the eurozone in particular. The performance has got worse the more the EU has developed joint policies and central controls.

Housing gets £4bn boost to increase number of new homes

The UK public warmed to the idea of spending our own money on our own priorities in the referendum campaign. The main issue between leave and remain was the money. Remain tried to dismiss its importance by claiming there was in practice little money at stake, and disagreed strongly with any reference to the gross figure for UK contributions.

The public did not take away one particular figure from the debate, but did believe that we contributed substantial money that it would be useful to spend at home. Cancelling the contributions would also make an important reduction in our large balance of payments deficit, as every penny we send and do not get back swells the deficit, just as surely as if we bought another import.

During the campaign I released a draft post-Brexit budget, showing how we could scrap VAT on domestic fuel, tampons and green products, and boost spending substantially on the NHS.

The government will be able to choose what to do once we have stopped the payments. The autumn statement showed a saving of a net contribution of £11.6bn in 2019-20 once we are out of the EU, as well as additional domestic spending in place of spending in the UK by the EU currently.

I am glad the chancellor has also adopted more flexible rules for the budget deficit. There is no need to genuflect to the Maastricht debt and deficit criteria once we leave, nor to pretend that we are about to get our overall debt down to 60% of GDP, as is required by those rules. The UK economy needs further stimulus, as the autumn statement acknowledged. There are roads and railway lines to be built, new power stations to be added, more water storage, schools and hospitals to cater for the rising population.

The government is right to say the UK needs to invest more. We need to make new provision for all the additional people who have joined the country in recent years, and to improve the efficiency of our infrastructure. The country is well behind in meeting demand for train and road capacity, and in energy provision.

The UK also needs to make, grow and provide more for its own needs. Leaving the EU will enable the UK to undertake a major campaign for import substitution. When we have our own fishing policy we could move back to being net exporters, instead of being importers. The common fisheries policy means too much of our fish is taken by other member states, leaving us short for our own needs. Designing our own agriculture policy will mean we can put behind us the quotas and regulations that have held back UK output during our years in the EU. We can change our procurement rules, so that the government when spending taxpayers’ money can ensure more is bought from home suppliers.

Why do we have a balance of payments surplus with the rest of the world but a deficit with our EU neighbours?

The UK is embarking on a substantial expansion of housebuilding. Too many materials and components for our new homes are imported. The lower level of sterling provides an opportunity for the UK to put in more brick, block and tile capacity, to prefabricate and manufacture more of the components and systems a new home needs. If more of the home is fabricated off-site – as happens in Germany and Scandinavia – we reduce the impact of bad weather, of labour shortages and other inefficiencies on the building site. Industry by industry there are opportunities for suitable investment and entrepreneurial activity, to meet more of the UK’s own demands. This will be good for jobs, and better for the environment, when more is produced close to the place of consumption.

One of the great unanswered questions of our time in the EU is: why do we run a balance of payments surplus with the rest of the world but a deficit with our EU neighbours? Why has it been so large and so persistent? Part of the reason rests in the way the EU rules were organised.

Early liberalisation was designed to help the sectors the continent was best at, rather than the sectors where the UK had a relative advantage. The continental competitors soon outpaced us in their better areas, leading to UK factory closures and job losses in areas like shipbuilding steel production and cars in the early years of membership. The special designs of the common agricultural and fishing policies also led to larger import bills for us.

Leaving the EU has coincided, so far, with a fall in the value of the pound. The UK should now be very competitive. It is time for business to respond to the favourable levels of domestic demand, and to work with government to put in the extra capacity we need to meet more of our own requirements. Prosperity, not austerity, should be the watchword.

Early liberalisation was designed to help the sectors the continent was best at, rather than the sectors where the UK had a relative advantage. The continental competitors soon outpaced us in their better areas, leading to UK factory closures and job losses in areas like shipbuilding steel production and cars in the early years of membership. The special designs of the common agricultural and fishing policies also led to larger import bills for us.

Leaving the EU has coincided, so far, with a fall in the value of the pound. The UK should now be very competitive. It is time for business to respond to the favourable levels of domestic demand, and to work with government to put in the extra capacity we need to meet more of our own requirements. Prosperity, not austerity, should be the watchword.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)