Bhutanatha Lake, Badami, India. Photograph: Chris Lisle/Corbis

Years ago, I scored a ticket to the first cricket Test match to be played in the city of Ahmedabad, Gujarat: India versus a West Indian 11 that included the peerless Viv Richards. I had expectations of an epic match as I joined other fans pushing into the brand new ground. But by the end, it was the performance of the spectators, not the players, that had staggered me. As the West Indians took the field, loud monkey-whoops filled the air, and banana skins rained down from the stands. The pelted players – probably the greatest West Indian team in history – stood there in their flannels, stunned.

Indians are rightly sensitive about racism directed at them; an Indian student beaten up in Australia, say, will swiftly become national news. Yet some Indians can be unthinkingly at ease with their own contempt for people of darker skin – a contradiction that warps both our present and our sense of the Indian past. As I travelled across India exploring the contemporary afterlives of 50 important historical figures spanning 2,500 years for Incarnations, my new book and 50-part BBC radio series, I heard dozens of young Indians extoll the bravery of Shivaji, the 17th-century Maratha warrior who defied the Mughals and serves today as a symbol of Hindu pride and resistance to Muslim rule. But when I mentioned a fierce resistor of Mughal expansion who came before Shivaji, young eyes went blank. For that forgotten leader doesn’t fall into any of the standard narrative silos of Indian history – Hindu, Muslim or European. Rather, he was an uncommonly clever and adaptive Ethiopian who had been shipped to India as a teenaged slave.

Years ago, I scored a ticket to the first cricket Test match to be played in the city of Ahmedabad, Gujarat: India versus a West Indian 11 that included the peerless Viv Richards. I had expectations of an epic match as I joined other fans pushing into the brand new ground. But by the end, it was the performance of the spectators, not the players, that had staggered me. As the West Indians took the field, loud monkey-whoops filled the air, and banana skins rained down from the stands. The pelted players – probably the greatest West Indian team in history – stood there in their flannels, stunned.

Indians are rightly sensitive about racism directed at them; an Indian student beaten up in Australia, say, will swiftly become national news. Yet some Indians can be unthinkingly at ease with their own contempt for people of darker skin – a contradiction that warps both our present and our sense of the Indian past. As I travelled across India exploring the contemporary afterlives of 50 important historical figures spanning 2,500 years for Incarnations, my new book and 50-part BBC radio series, I heard dozens of young Indians extoll the bravery of Shivaji, the 17th-century Maratha warrior who defied the Mughals and serves today as a symbol of Hindu pride and resistance to Muslim rule. But when I mentioned a fierce resistor of Mughal expansion who came before Shivaji, young eyes went blank. For that forgotten leader doesn’t fall into any of the standard narrative silos of Indian history – Hindu, Muslim or European. Rather, he was an uncommonly clever and adaptive Ethiopian who had been shipped to India as a teenaged slave.

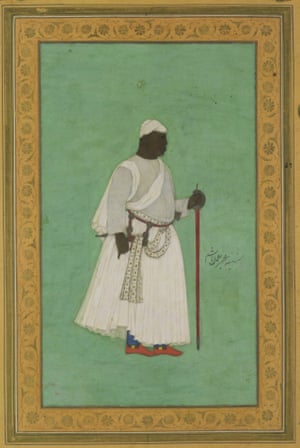

The rise and historical eclipse of the most powerful African in Indian history, Malik Ambar (1548-1626), is just one of the effacements and distortions I explored in Incarnations. I intended my book to complicate reigning western stereotypes – of India as a land of mystical but not intellectual traditions; of the Indian agrarian poor as meek and passive; of a culture and an economy only recently woken up to globalisation. But I wanted to wrestle as well with how Indians’ own prejudices and stereotypes – regarding race, faith, gender, caste and respect for individuality itself – contribute to the murky way Indian history gets told. Clarifying the story of Malik Ambar might be a good place to start.

***

We usually think of the African slave trade as running from east to west, but there was a thriving, little-remembered traffic that sailed eastwards to India, too. Indian rulers, particularly on Western India’s vast Deccan plain, acquired their human chattel from Arab traders in exchange for luxurious cloth. Kings and sultans, perpetually battling each other for territory and treasure, prized the African slaves as warriors. Thus in the mid-16th century, Malik Ambar was among the adolescent cargo offloaded on the Konkan coast.

Sold into slavery as a child by his impoverished parents, and converted by Muslim masters, the teenager arrived on the subcontinent having acquired an arsenal of non-martial skills – multiple languages, irrigation engineering, administration and accounting among them. As he passed through the hands of Deccan potentates, he became recognised not just as a soldier, but as a military and political strategist. Finally freed upon the death of a master whose power he had helped secure, he quickly amassed power of his own. Leading a mercenary army of crack horsemen that ultimately grew to a force of 50,000, he became a lethal accessory to Deccan rulers hoping to resist the expansionist aims of Mughal emperor Akbar and his son Jahangir. Through guerrilla tactics and night-time raids in the craggy, ravined landscape of the Deccan, Malik Ambar severed Mughal supply lines, stopped their southward thrust and gained control over large swaths of the region.

Malik Ambar

Emperor Jahangir, frustrated by his inability to defeat the powerful Ethiopian, actually took to commissioning gruesome miniature paintings in which he slayed his nemesis on paper. Jahangir might have been chuffed had he foreseen the future, which secured the elimination of Malik Ambar he so furiously sought. Malik Ambar wasn’t a Hindu native defending some ancient motherland. He was a dark-skinned, Muslim outsider, and thereby destined to be diminished. Descendents of African slaves now live poor and ghettoised, many of them in Gujarat, where I saw the legendary West Indian cricketers mocked as monkeys. And children growing up in those shunned communities will find no mention in their schoolbooks of a self-made power entrepreneur whose skin colour and lineage they share.

***

Both Indian and western approaches to the subcontinent’s past tend to ignore the experiences of individuals who don’t fit into grand narratives: stories (in India) of national uplift, religious unity or cultural cohesion, and (in the west) of a herd-like, prayerful and sometimes petulant nation just shaking off the hangover of colonisation. The misconstruals leave many people, inside and outside the country, with what is, at best gloss, a young-adult version of Indian history. To my mind, India’s real history is something like the Malik Ambar story writ large: unpredictable, eccentric, internationally connected and compelling fresh attention – not least for what it tells us about India now.

We have seen what happens when cultural biases run against a historical figure. So what if the biases run in the figure’s favour? That individual often gets turned into a demi-god, while the experiences of the actual, inconsistent human being fall away. As I chased down historical lives in far-flung communities, at archaeological sites, and in archives and texts, I sometimes noticed an almost comical gap between the superhero guises some figures are forced to wear today and their own self-critical sensibilities. One such was India’s first global guru, who brought yoga to the west: the baby-faced, proselytising monk known as Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902). Nowadays in India he is portrayed as the heroic personification of modern muscular Hinduism, a man insistent about the superiority of his religion over all others. (He is also a personal hero of Indian prime minister Narendra Modi.) Less well remembered is the Vivekananda who could be a perceptive critic of Hindu society.

FacebookTwitterPinterest Swami Vivekananda

Vivekananda’s fame derived from lectures on Hinduism that he delivered in flamboyant, saffron-robed style across America and Europe in the 1890s. But even as he took those audiences by storm (“I give them spirituality, and they give me money,” he wrote with a wink to one of his Indian patrons), he was deeply shaken by his first encounters with an egalitarianism and social progressiveness that his fellow Hindus lacked. Visiting a Massachusetts women’s penitentiary, he was astonished by the dignity even criminals were afforded. “Oh, how my heart ached to think of what we think of the poor, the low in India,” he wrote to a friend back home. “They have no chance, no escape, no way to climb up … They have forgotten that they too are men. And the result is slavery.”

The contradictions lacing Vivekananda’s speeches and letters – on whether caste was integral to Hinduism, on the validity of certain Hindu rituals and customs – intimate the depth of his intellectual struggle, and one of his greatest internal conflicts was with the effect of his faith on the powerless. “No religion on earth preaches the dignity of humanity in such a lofty strain as Hinduism,” he would write, “and no religion treads upon the necks of the poor and low in such a fashion as Hinduism.” But such contours in Vivekananda’s personality and intellectual life got flattened during his conversion into a laminated image: that of righteous Hindu nationalist avenger of the Muslim and colonial conquests of India, ambivalent about nothing at all.

***

In modern India, writers and historians have been intimidated – and libraries and bookshops ransacked – when they have dared to treat vaunted figures as historical beings. By insisting that favourites from India’s past be preserved in memory as godlike, full of certitude and above human consideration, we don’t just deny them their real natures, we sabotage their exemplary force.

Indian sexism being even more deeply rooted than racism, I can’t claim I was surprised to find that there were far fewer historical records for significant female lives than there were for their male counterparts. But what I saw more clearly is how an absence of documentary sources plays into our ridiculous cultural tendency to turn real women of intellect, judgment, fallibility and bravery into goddess-types

.

The Accession of the Queen of India, 1858. Illustration: Print Collector/Getty Images

Consider Lakshmi Bai (1828-1858), the Rani or Queen of Jhansi, who gained mythic status in the colonial and nationalist Indian imagination because of her resistance to British rule during the uprising of 1857. Today, Indian schoolchildren know her for a single iconic image: astride a leaping horse, sword raised high, with her adopted son clinging to her back. The British military are about to conquer her fort, and instead of surrendering, she is making a dramatic midnight escape from the ramparts.

When I looked down from the fort walls she supposedly leapt from, only one word came to mind: “Splat.” An itinerant priest hiding in her fort at the time described a more plausible exit scenario: down a back staircase and into the night-black hills. For their part, the British preserved the queen in memory as a tempestuous 19th-century villainess. “This Jezebel Ranee”, as a British officer termed her, has since animated a host of adventure and romance novels.

Neither western nor Indian tales leave much room for the actual, practical, Earth-bound person who ruled over a mid-sized kingdom around 400km south of Delhi. So it is a relief to gain, from the priest’s observations, a glimpse of the sort of woman rarely seen in royal Indian annals. This strong-willed queen is athletic (weightlifting, wrestling and steeplechase were just her pre-breakfast routine); indifferent to regal trappings (in contrast to her crossdressing husband); and hands-on as a ruler (so much so that she punished criminals herself, with the whack of a stick).

Following the death of her husband, the land-hungry British annexed Jhansi under a doctrine that enabled them to snaffle up princely states. Lakshmi Bai tried to get her dominion back through a series of frustrating negotiations, but when diplomacy faltered, she decided that rebelling sepoys marching from the north in 1857 might help strengthen her claims. After she harboured them in her fort, though, they massacred British officers and their families, upon which the British bombed her fort, then breached the walls. Two months after her escape, they killed her.

To ascribe to Lakshmi Bai motivations more complex than protonational ones, or escapes that chime with the laws of physics, isn’t to cut her down to size; it is to acknowledge a woman whose independence and unconventionality are qualities more relevant to contemporary women then supposed supernatural powers.

Given how little documentation we have of powerful women in the pre-independence pantheon, what is lost when we turn away from real historical evidence is painful. Take a 20th-century icon from a different realm: the magnificent south Indian classical singer MS Subbulakshmi. Born in 1916 into the Devadasi tradition – a lineage of temple courtesans, whose job was to entertain and serve rich and upper-caste men – she built a career that took her from Madurai temple custom to film stardom to the embodiment of independent India’s national culture

The Accession of the Queen of India, 1858. Illustration: Print Collector/Getty Images

Consider Lakshmi Bai (1828-1858), the Rani or Queen of Jhansi, who gained mythic status in the colonial and nationalist Indian imagination because of her resistance to British rule during the uprising of 1857. Today, Indian schoolchildren know her for a single iconic image: astride a leaping horse, sword raised high, with her adopted son clinging to her back. The British military are about to conquer her fort, and instead of surrendering, she is making a dramatic midnight escape from the ramparts.

When I looked down from the fort walls she supposedly leapt from, only one word came to mind: “Splat.” An itinerant priest hiding in her fort at the time described a more plausible exit scenario: down a back staircase and into the night-black hills. For their part, the British preserved the queen in memory as a tempestuous 19th-century villainess. “This Jezebel Ranee”, as a British officer termed her, has since animated a host of adventure and romance novels.

Neither western nor Indian tales leave much room for the actual, practical, Earth-bound person who ruled over a mid-sized kingdom around 400km south of Delhi. So it is a relief to gain, from the priest’s observations, a glimpse of the sort of woman rarely seen in royal Indian annals. This strong-willed queen is athletic (weightlifting, wrestling and steeplechase were just her pre-breakfast routine); indifferent to regal trappings (in contrast to her crossdressing husband); and hands-on as a ruler (so much so that she punished criminals herself, with the whack of a stick).

Following the death of her husband, the land-hungry British annexed Jhansi under a doctrine that enabled them to snaffle up princely states. Lakshmi Bai tried to get her dominion back through a series of frustrating negotiations, but when diplomacy faltered, she decided that rebelling sepoys marching from the north in 1857 might help strengthen her claims. After she harboured them in her fort, though, they massacred British officers and their families, upon which the British bombed her fort, then breached the walls. Two months after her escape, they killed her.

To ascribe to Lakshmi Bai motivations more complex than protonational ones, or escapes that chime with the laws of physics, isn’t to cut her down to size; it is to acknowledge a woman whose independence and unconventionality are qualities more relevant to contemporary women then supposed supernatural powers.

Given how little documentation we have of powerful women in the pre-independence pantheon, what is lost when we turn away from real historical evidence is painful. Take a 20th-century icon from a different realm: the magnificent south Indian classical singer MS Subbulakshmi. Born in 1916 into the Devadasi tradition – a lineage of temple courtesans, whose job was to entertain and serve rich and upper-caste men – she built a career that took her from Madurai temple custom to film stardom to the embodiment of independent India’s national culture

.

MS Subbulakshmi

Standing in her modest childhood home, on an alleyway near a temple, I mentally tallied the series of steely calculations that launched the stigmatised, artistic child of a single mother into the Indian cultural canon. Once her prodigious gift was recognised, she broke with her mother and her home town, took a renowned musician and then a canny manager as lovers, and sought out the musicians she admired most, to help develop her talent. The few letters of hers not destroyed by image keepers are rife with attitude and passion. But her public persona was, and remains – she died aged 88 in 2004 – that of a demure housewife whose accomplishments were simply visited upon her by the gods. As in other stories of exceptional, hard-working Indian women, volition and ambition are denied their rightful roles.

***

A different narrowing of historical understanding happens when an individual is turned into a representative emblem of his group. Take Bhimrao Ambedkar, who was born an untouchable (as Dalits were formerly known) and then made himself one of the most educated men in India. Acquiring PhDs from the LSE and Columbia University, where his professors included the pragmatist philosopher John Dewey, Ambedkar returned home with a vision of India’s future unique among his mostly upper-caste nationalist contemporaries. Invited by them to play an important role in writing the Indian Constitution, he managed to implant within it some of its most radical ideas, including the principle of affirmative action.

In my travels I heard people of higher castes described Ambedkar as “the big boss” of the Dalits– as if Ambedkar was of no particular concern to other Indians. That chiselled-down identity made me wince, because he is also one of the 20th-century’s great, cranky public intellectuals, of any nation– India’s Tocqueville, really, with enduring insights into the structure and psychology of democracy in general. Where India’s nationalist elite put faith in parliaments and political rights, economic development, or social and cultural reform, Ambedkar saw educational equality as the essential bedrock of a truly democratic society. He understood the limitations of constitutions, and, in a prescient analysis, he argued that without the parity and fraternity created by making education equally accessible to Indians of every background and caste, social barriers would prevail and all efforts at reforming society (including radical ones) would founder.

***

British imperialists liked to suggest Indians were indifferent to their history, and inept at independent thinking to boot, because of their attachment to doll-like gods and caste rituals. This was a self-justifying analysis, of course, given that the Raj was pillaging the subcontinent’s historical wealth with the same voraciousness as it had plundered the teakwood and tea. Still, it was a longstanding colonial habit to picture the empire’s jewel as a congeries of religions, castes and languages: in effect, a black hole of community belonging and identity, from which few flickers of individuality escaped.

MS Subbulakshmi

Standing in her modest childhood home, on an alleyway near a temple, I mentally tallied the series of steely calculations that launched the stigmatised, artistic child of a single mother into the Indian cultural canon. Once her prodigious gift was recognised, she broke with her mother and her home town, took a renowned musician and then a canny manager as lovers, and sought out the musicians she admired most, to help develop her talent. The few letters of hers not destroyed by image keepers are rife with attitude and passion. But her public persona was, and remains – she died aged 88 in 2004 – that of a demure housewife whose accomplishments were simply visited upon her by the gods. As in other stories of exceptional, hard-working Indian women, volition and ambition are denied their rightful roles.

***

A different narrowing of historical understanding happens when an individual is turned into a representative emblem of his group. Take Bhimrao Ambedkar, who was born an untouchable (as Dalits were formerly known) and then made himself one of the most educated men in India. Acquiring PhDs from the LSE and Columbia University, where his professors included the pragmatist philosopher John Dewey, Ambedkar returned home with a vision of India’s future unique among his mostly upper-caste nationalist contemporaries. Invited by them to play an important role in writing the Indian Constitution, he managed to implant within it some of its most radical ideas, including the principle of affirmative action.

In my travels I heard people of higher castes described Ambedkar as “the big boss” of the Dalits– as if Ambedkar was of no particular concern to other Indians. That chiselled-down identity made me wince, because he is also one of the 20th-century’s great, cranky public intellectuals, of any nation– India’s Tocqueville, really, with enduring insights into the structure and psychology of democracy in general. Where India’s nationalist elite put faith in parliaments and political rights, economic development, or social and cultural reform, Ambedkar saw educational equality as the essential bedrock of a truly democratic society. He understood the limitations of constitutions, and, in a prescient analysis, he argued that without the parity and fraternity created by making education equally accessible to Indians of every background and caste, social barriers would prevail and all efforts at reforming society (including radical ones) would founder.

***

British imperialists liked to suggest Indians were indifferent to their history, and inept at independent thinking to boot, because of their attachment to doll-like gods and caste rituals. This was a self-justifying analysis, of course, given that the Raj was pillaging the subcontinent’s historical wealth with the same voraciousness as it had plundered the teakwood and tea. Still, it was a longstanding colonial habit to picture the empire’s jewel as a congeries of religions, castes and languages: in effect, a black hole of community belonging and identity, from which few flickers of individuality escaped.

A procession held in 2015 to mark the anniversary of the birth of Bhim Rao Ambedkar in Mumbai, India. Photograph: Rafiq Maqbool/AP

And weren’t those minimally individuated Indians gentle and spiritual as they waited for their next karmic promotion? I was therefore delighted, visiting Mysore, to hold a tray bearing a palm leaf manuscript from around the turn of the Christian millennium that, when rediscovered a century ago, summarily exploded such cliches. The Arthashastra, a detailed treatise on statecraft and the art of government, gave counsel to kings that made Machiavelli’s look milquetoast (one gets a hint from the chapter titles, which feel as if they were written this year, perhaps by a parliamentary investigative committee: “Establishment of Clandestine Operatives”, “Pacifying a Territory Gained”, “Surveillance of People with Secret Income” and “Investigation through Interrogation and Torture”). The author was a man known as Kautilya, and, though all we have of him is this text, it gives a tantalising rebuttal to suggestions that ancient Indian interests were primarily spiritual.

As I worked, I was moved by how many of the 50 lives I studied posed pointed challenges to the Indian present

As does another work of analytic intellect, by the 5BCE master of the Sanskrit language, Panini. In what amounts to a mere 40 pages, he created the most complete linguistic system in history. This masterwork, known as The Ashtadhyayi, helped make Sanskrit the lingua franca of the Asian world for more than 1,000 years. Today, Panini’s system would be called a generative grammar, something modern linguistic philosophers such as Noam Chomsky and his students have been working for the past half century to develop. It is arguably from the Sanskrit tradition – whose logic Panini helped explain – that India’s present-day century software revolution emerged. And then there’s Ramanujan, the young mathematics prodigy whose century-old notebook scribblings are, as we speak, helping other scientists unravel the nature of the universe. Perhaps there’s something mystical there, in the postulates of quantum physics; though I don’t think it’s what the colonialists had in mind.

***

Other western misperceptions still present themselves on a daily basis – for instance, the notion that social conditions are uniformly dismal across India. Consider the unaddressed crimes and daily oppressions against Indian women, which have rightly provoked international outrage. Draw closer, and you will see that the outrage obscures telling differences between the opportunities for women in northern India and women in the more progressive south, where child marriage and fertility rates are far lower, and female literacy and work participation rates far higher. Some of that divergence has to do not with culture, but with reform-inspired historical crusades – including one led by a Tamil primary-school dropout known as Periyar (1879-1973).

He was an atheist and rationalist (beliefs that can get you killed in India today), and from the 1920s waged an intellectual campaign against the upper-caste northerners dominating the national movement. Setting himself up as the anti-Gandhi (wearing black, to counter Gandhi’s habit of dressing in white), he pressed for equal treatment of the lower castes, greater recognition of southern culture and language and, above all, greater freedoms for women in a country where wagons were still circled around the patriarchal family. For almost half a century, he advocated women’s rights and unhindered access to contraception. The further I delved into his story, and those of other social reformers, the more strongly I was reminded of how, under sustained pressure, even rigid societies can be changed.

***

Occasionally, walking through slum or village lanes to research Incarnations, I overheard teenagers cheerfully explaining to their friends what I was up to – it went along the lines of: “He’s telling the story of how India became number one.” Indeed, it is a habit of national histories to justify the present as the perfect and necessary outcome of what came before. But as I worked, I was moved by how many of the 50 lives I studied posed, like Malik Ambar’s life, pointed challenges to the Indian present.

Mahatma Gandhi with his two granddaughters in 1947. Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

Through religious collisions, and philosophical and ethical explorations, those individuals were part of intense arguments that have kept going for millennia: about what kind of life is worth living, what kind of society is worth having, which hierarchies are morally legitimate, what role religion has in the political and legal order, what kind of love is valid, who owns the water and land, and what kind of place India should be. A civilisation able to produce a Buddha, a Mahavira, a Mirabai, a Birsa Munda, an Amrita Sher-Gil, a Muhammad Iqbal, an Ambedkar and a Gandhi is a place open both to radical experiments with self-definition and productive arguments about what a country and its people should value. That creative energy is worth recalling at a time when some in India seek to transform a ferment of ideas into a singular religious concoction.

Despite the current, cramped political climate, or maybe because of it, it seemed to me an essential moment to push for a deeper discussion of the Indian past – and not for the benefit of Indians alone. We are done now with the age in which what happened in India was considered peripheral to what used to be called the first world. Back then, those who wrote about the country had to make arguments for its relevance to, for instance, the larger story of democracy. Meanwhile, some of the most compelling minds from India’s past were forced to exist in splendid isolation, instead of being recognised for what they really were: figures engaged with other individuals and ideas across time, across borders. Today, India, in both its positive and negative aspects, is becoming central to discussions about the world at large. So it is time to reconsider not just the stories Indians like to tell themselves, but also the stories the world tells about us.

Bowling with a remodelled action during a match against Kenya in December 2014, a few months after he was banned © AFP

Bowling with a remodelled action during a match against Kenya in December 2014, a few months after he was banned © AFP "Working with Saqlain bhai, I changed my action eight times" © ESPNcricinfo Ltd

"Working with Saqlain bhai, I changed my action eight times" © ESPNcricinfo Ltd "I have this belief inside. I believe that everything I can put my head to, I can achieve" © Getty Images

"I have this belief inside. I believe that everything I can put my head to, I can achieve" © Getty Images