Uri Avnery in Outlook India

I MUST start with a shocking confession: I am not afraid of the Iranian nuclear bomb.

I know that this makes me an abnormal person, almost a freak.

But what can I do? I am unable to work up fear, like a real Israeli. Try as I may, the Iranian bomb does not make me hysterical.

MY FATHER once taught me how to withstand blackmail: imagine that the awful threat of the blackmailer has already come about. Then you can tell him: Go to hell.

I have tried many times to follow this advice and found it sound. So now I apply it to the Iranian bomb: I imagine that the worst has already happened: the awful ayatollahs have got the bombs that can eradicate little Israel in a minute.

So what?

According to foreign experts, Israel has several hundred nuclear bombs (assessments vary between 80-400). If Iran sends its bombs and obliterates most of Israel (myself included), Israeli submarines will obliterate Iran. Whatever I might think about Binyamin Netanyahu, I rely on him and our security chiefs to keep our "second strike" capability intact. Just last week we were informed that Germany had delivered another state-of-the-art submarine to our navy for this purpose.

Israeli idiots — and there are some around — respond: "Yes, but the Iranian leaders are not normal people. They are madmen. Religious fanatics. They will risk the total destruction of Iran just to destroy the Zionist state. Like exchanging queens in chess."

Such convictions are the outcome of decades of demonizing. Iranians — or at least their leaders — are seen as subhuman miscreants.

Reality shows us that the leaders of Iran are very sober, very calculating politicians. Cautious merchants in the Iranian bazaar style. They don't take unnecessary risks. The revolutionary fervor of the early Khomeini days is long past, and even Khomeini would not have dreamt of doing anything so close to national suicide.

ACCORDING TO the Bible, the great Persian king Cyrus allowed the captive Jews of Babylon to return to Jerusalem and rebuild their temple. At that time, Persia was already an ancient civilization — both cultural and political.

After the "return from Babylon", the Jewish commonwealth around Jerusalem lived for 200 years under Persian suzerainty. I was taught in school that these were happy years for the Jews.

Since then, Persian culture and history has lived through another two and a half millennia. Persian civilization is one of the oldest in the world. It has created a great religion and influenced many others, including Judaism. Iranians are fiercely proud of that civilization.

To imagine that the present leaders of Iran would even contemplate risking the very existence of Persia out of hatred of Israel is both ridiculous and megalomaniac.

Moreover, throughout history, relations between Jews and Persians have almost always been excellent. When Israel was founded, Iran was considered a natural ally, part of David Ben-Gurion's "strategy of the periphery" — an alliance with all the countries surrounding the Arab world.

The Shah, who was re-installed by the American and British secret services, was a very close ally. Teheran was full of Israeli businessmen and military advisers. It served as a base for the Israeli agents working with the rebellious Kurds in northern Iraq who were fighting against the regime of Saddam Hussein.

After the Islamic revolution, Israel still supported Iran against Iraq in their cruel 8-year war. The notorious Irangate affair, in which my friend Amiram Nir and Oliver North played such an important role, would not have been possible without the old Iranian-Israeli ties.

Even now, Iran and Israel are conducting amiable arbitration proceedings about an old venture: the Eilat-Ashkelon oil pipeline built jointly by the two countries.

If the worst comes to the worst, nuclear Israel and nuclear Iran will live in a Balance of Terror.

Highly unpleasant, indeed. But not an existential menace.

HOWEVER, FOR those who live in terror of the Iranian nuclear capabilities, I have a piece of advice: use the time we still have.

Under the American-Iranian deal, we have at least 10 years before Iran could start the final phase of producing the bomb.

Please use this time for making peace.

The Iranian hatred of the "Zionist Regime" — the State of Israel — derives from the fate of the Palestinian people. The feeling of solidarity for the helpless Palestinians is deeply ingrained in all Islamic peoples. It is part of the popular culture in all of them. It is quite real, even if the political regimes misuse, manipulate or ignore it.

Since there is no ground for a specific Iranian hatred of Israel, it is solely based on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. No conflict, no enmity.

Logic tells us: if we have several years before we have to live in the shadow of an Iranian nuclear bomb, let's use this time to eliminate the conflict. Once the Palestinians themselves declare that they consider the historic conflict with Israel settled, no Iranian leadership will be able to rouse its people against us.

FOR SEVERAL weeks now, Netanyahu has been priding himself publicly on a huge, indeed historic, achievement.

For the first time ever, Israel is practically part of an Arab alliance.

Throughout the region, the conflict between Muslim Sunnis and Muslim Shiites is raging. The Shiite camp, headed by Iran, includes the Shiites in Iraq, Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen. (Netanyahu falsely — or out of ignorance — includes the Sunni Hamas in this camp.)

The opposite Sunni camp includes Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the Gulf states. Netanyahu hints that Israel is now secretly accepted by them as a member.

It is a very untidy picture. Iran is fighting against the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, which is a mortal enemy of Israel. Iran is supporting the Assad regime in Damascus, which is also supported by Hezbollah, which fights against the lslamic State, while the Saudis support other extreme Sunni Syrians who fight against Assad and the Islamic State. Turkey supports Iran and the Saudis while fighting against Assad. And so on.

I am not enamored with Arab military dictatorships and corrupt monarchies. Frankly, I detest them. But if Israel succeeds in becoming an official member of any Arab coalition, it would be a historic breakthrough, the first in 130 years of Zionist-Arab conflict.

However, all Israeli relations with Arab countries are secret, except those with Egypt and Jordan, and even with these two the contacts are cold and distant, relations between the regimes rather than between the peoples.

Let's face facts: no Arab state will engage in open and close cooperation with Israel before the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is ended. Even kings and dictators cannot afford to do so. The solidarity of their peoples with the oppressed Palestinians is far too profound.

Real peace with the Arab countries is impossible without peace with the Palestinian people, as peace with the Palestinian people is impossible without peace with the Arab countries.

So if there is now a chance to establish official peace with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States, and to turn the cold peace with Egypt into a real one, Netanyahu should jump at it. The terms of an agreement are already lying on the table: the Saudi peace plan, also called the Arab Initiative, which was adopted many years ago by the entire Arab League. It is based on the two-state solution of the Israeli-Arab conflict.

Netanyahu could amaze the whole world by "doing a de Gaulle" — making peace with the Sunni Arab world (as de Gaulle did with Algeria) which would compel the Shiites to follow suit.

Do I believe in this? I do not. But if God wills it, even a broomstick can shoot.

And on the day of the Jewish Pesach feast, commemorating the (imaginary) exodus from Egypt, we are reminding ourselves that miracles do happen.

'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Sunday, 12 April 2015

Saturday, 11 April 2015

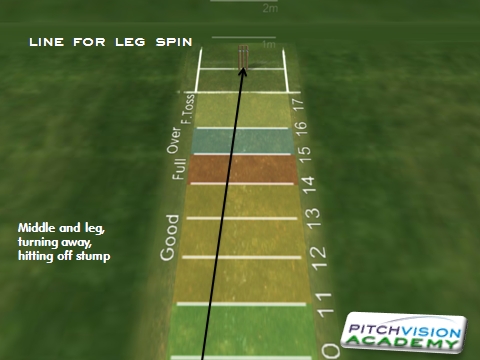

Where Do High Class Spinners Pitch the Ball?

In another guest article, club left arm spinner AB talks us through exactly where to land the ball to cause maximum damage to batsmen’s averages. Courtesy Pitchvision Academy

We all know the key to top quality spin bowling is to bowl a consistent line and length. But what does that actually mean?

First we need to figure out where is the best length to bowl.

We want a length that is full enough that the batsman is forced to come forward, but not so full that he is able to reach the ball on the half volley without mis-hitting it.

Consider that the average spin bowler delivers the ball at approximately 50mph, and that after bouncing the speed of the ball is reduced by about 50%. This translates to a speed of about 10 metres a second. The average reaction time of a human is 0.2s. If we pitch the ball within 2 metres of the batsman, then he will be unable to play back as he would simply not have time to react to any movement off the pitch.

Therefore the maximum distance away from the batsman's stumps that we should land the ball, given that he will move back one foot when playing back, is approximately 11 foot. Anything shorter than 11 foot and the batsman will be able to play comfortably off the back foot.

How about minimum distance?

A batsman playing on the front foot normally plays the ball about 3 feet in front of his crease. The ideal location to pitch the ball is the one at which the ball has just turned enough to hit or just miss the edge of the bat. On a normal pitch, we will find the ball turning something in the order of 5 degrees, which translates to about 1 inch sideways for each foot after bouncing.

Therefore we need to pitch the ball between 2 and 4 foot in front of the bat (8 to 10 foot from the stumps) in order to take the edge.

On a turning track, a ball pitching only a foot in front of the bat would be sufficient to threaten the edge.

The best length on this pitch would therefore be between 7 and 9 foot from the batsman's stumps. So the spin bowler has an area of about 4 feet, or just over a metre, in which to aim: anything inside this will pose the batsman problems.

------Also read

Good Length and Right Speed

-------

Spinner’s line

No matter the pitch, the ball will not always turn a consistent amount. This variability of turn is major positive factor for the spinner. If he can't predict what will happen, how can the batsman be expected to?

A competent batsman will most likely play the percentages and play for a small amount of turn when defending off the front foot, reducing the likelihood of a ball that turns just 1 or 2 inches catching the edge. However, the inadvertent result of this is that now both the big turning delivery and the straight ball are the potential wicket taking deliveries. The spinner must always take advantage of this by ensuring that every time the ball beats the bat, whether the inside edge or outside edge, then there is a decent probability that the batsman will be dismissed.

Batsmen are able to play more assertively when they feel comfortable that they are able to use their pad as a second line of defence without the risk of being dismissed lbw. This is why it’s important for a spin bowler to constantly attack the stumps with either the big spinning delivery, the straight ball, or both.

We therefore want to keep as many deliveries as possible ending up in the danger zone: either on the stumps for a chance of bowled or lbw or within 6 inches of off stump for a likely caught behind chance.

On a spinning pitch, then 10 degrees of turn will translate to a difference of about 15 inches between the straight ball and the big turning delivery. So we need to take this into consideration when planning our line of attack.

If the ball is turning away from the batsman, the ideal stock line is to pitch the ball on middle and leg, with the straight delivery angled in towards leg stump. Spin the ball hard enough for the spinning delivery to hit or go past the top of off stump.

The batsman will then be forced to play down a middle stump line to defend against the spin, and this will mean that both the straight delivery and the big spinner will have a good chance of dismissing him.

The off spinner should ensure that his big spinning delivery is not wasted by constantly turning down the leg side. This means that he needs to pitch the ball just outside off stump. A sensible batsman will then play down the line of off stump to defend against the spin, leaving both the big spinner and the straight ball as wicket-taking options.

Benaud - the wise old king

Gideon Haigh in Cricinfo

If we don't remember him as an elite legspinner, a thinking captain or one of cricket's true professionals, it's because of the phenomenal work he has done as a commentator, writer and observer

If Arlott was the voice of cricket, Benaud was the face © Getty Images

"Did you ever play cricket for Australia, Mr Benaud?" In his On Reflection, Richie Benaud recalls being asked this humbling question by a "fair-haired, angelic little lad of about 12", one of a group of six autograph seekers who accosted him at the SCG "one December evening in 1982".

"Now what do you do?" Benaud writes. "Cry or laugh? I did neither but merely said yes, I had played up to 1963, which was going to be well before he was born. 'Oh,' he said. 'That's great. I thought you were just a television commentator on cricket.'" Autograph in hand, the boy "scampered away with a 'thank you' thrown over his shoulder".

It is a familiar anecdotal scenario: past player confronted by dwindling renown. But the Benaud version is very Benaudesque. There is the amused self-mockery, the precise observation, the authenticating detail: he offers a date, the number of boys and a description of the appearance of his interlocutor, whose age is cautiously approximated.

In his story Benaud indulges the boy's solecism, realising that it arises not merely from youthful innocence but from the fact that "he had never seen me in cricket gear, and knew me only as the man who did the cricket on Channel 9". Then he segues into several pages of discussion of the changed nature of the cricket audience, ending with a self-disclosing identification. "Some would say such a question of that kind showed lack of respect or knowledge. Not a bit of it… what it did was show an inquiring mind and I'm all in favour of inquiring minds among our young sportsmen. Perhaps that is because I had an inquiring mind when I came into first-class cricket but was not necessarily allowed to exercise it in the same way as young players are now."

I like this passage; droll, reasoned and thoughtful, it tells us much about cricket's most admired and pervasive post-war personality. It is the voice, as Greg Manning phrased it inWisden Australia, of commentary's "wise old king". It betrays, too, the difficulty in assessing him: in some respects Benaud's abiding ubiquity in England and Australia inhibits appreciation of the totality of his achievements.

In fact, Benaud would rank among Test cricket's elite legspinners and captains if he had never uttered or written a word about the game. His apprenticeship was lengthy - thanks partly to the prolongation of Ian Johnson's career by his tenure as Australian captain - and Benaud's first 27 Tests encompassed only 73 wickets at 28.90 and 868 runs at 28.66.

Then, as Johnnie Moyes put it, came seniority and skipperhood: "Often in life and in cricket we see the man who has true substance in him burst forth into stardom when his walk-on part is changed for one demanding personality and a degree of leadership. I believe that this is what happened to Benaud." In his next 23 Tests, Benaud attained the peak of proficiency - 131 wickets at 22.66 and 830 runs at 28.62, until a shoulder injury in May 1961 impaired his effectiveness.

Australia did not lose a series under Benaud's leadership, although he was defined by his deportment as much as his deeds. Usually bareheaded, and with shirt open as wide as propriety permitted, he was a colourful, communicative antidote to an austere, tight-lipped era. Jack Fingleton likened Benaud to Jean Borotra, the "Bounding Basque of Biarritz" over whom tennis audiences had swooned in the 1920s. Wisden settled for describing him as "the most popular captain of any overseas team to come to Great Britain".

One of Benaud's legacies is the demonstrative celebration of wickets and catches, which was a conspicuous aspect of his teams' communal spirit and is today de rigeur. Another is a string of astute, astringent books, including Way of Cricket (1960) and A Tale of Two Tests (1962), which are among the best books written by a cricketer during his career. "In public relations to benefit the game," Ray Robinson decided, "Benaud was so far ahead of his predecessors that race-glasses would have been needed to see who was at the head of the others."

Benaud's reputation as a gambling captain has probably been overstated. On the contrary he was tirelessly fastidious in his planning, endlessly solicitous of his players and inclusive in his decision-making. Benaud receives less credit than he deserves for intuiting that "11 heads are better than one" where captaincy is concerned; what is commonplace now was not so in his time. In some respects his management model paralleled the "human relations school" in organisational psychology, inspired by Douglas McGregor's The Human Side of Enterprise(1960). Certainly Benaud's theory that "cricketers are intelligent people and must be treated as such", and his belief in "an elastic but realistic sense of self-discipline" could be transliterations of McGregor to a sporting context.

Ian Meckiff defined Benaud as "a professional in an amateur era", a succinct formulation that may partly explain the ease with which he has assimilated the professional present. For if a quality distinguishes his commentary, it is that he calls the game he is watching, not one he once watched or played in. When Simon Katich was awarded his baggy green at Headingley in 2001, it was Benaud whom Steve Waugh invited to undertake the duty.

"Did you ever play cricket for Australia, Mr Benaud?" In his On Reflection, Richie Benaud recalls being asked this humbling question by a "fair-haired, angelic little lad of about 12", one of a group of six autograph seekers who accosted him at the SCG "one December evening in 1982".

"Now what do you do?" Benaud writes. "Cry or laugh? I did neither but merely said yes, I had played up to 1963, which was going to be well before he was born. 'Oh,' he said. 'That's great. I thought you were just a television commentator on cricket.'" Autograph in hand, the boy "scampered away with a 'thank you' thrown over his shoulder".

It is a familiar anecdotal scenario: past player confronted by dwindling renown. But the Benaud version is very Benaudesque. There is the amused self-mockery, the precise observation, the authenticating detail: he offers a date, the number of boys and a description of the appearance of his interlocutor, whose age is cautiously approximated.

In his story Benaud indulges the boy's solecism, realising that it arises not merely from youthful innocence but from the fact that "he had never seen me in cricket gear, and knew me only as the man who did the cricket on Channel 9". Then he segues into several pages of discussion of the changed nature of the cricket audience, ending with a self-disclosing identification. "Some would say such a question of that kind showed lack of respect or knowledge. Not a bit of it… what it did was show an inquiring mind and I'm all in favour of inquiring minds among our young sportsmen. Perhaps that is because I had an inquiring mind when I came into first-class cricket but was not necessarily allowed to exercise it in the same way as young players are now."

I like this passage; droll, reasoned and thoughtful, it tells us much about cricket's most admired and pervasive post-war personality. It is the voice, as Greg Manning phrased it inWisden Australia, of commentary's "wise old king". It betrays, too, the difficulty in assessing him: in some respects Benaud's abiding ubiquity in England and Australia inhibits appreciation of the totality of his achievements.

In fact, Benaud would rank among Test cricket's elite legspinners and captains if he had never uttered or written a word about the game. His apprenticeship was lengthy - thanks partly to the prolongation of Ian Johnson's career by his tenure as Australian captain - and Benaud's first 27 Tests encompassed only 73 wickets at 28.90 and 868 runs at 28.66.

Then, as Johnnie Moyes put it, came seniority and skipperhood: "Often in life and in cricket we see the man who has true substance in him burst forth into stardom when his walk-on part is changed for one demanding personality and a degree of leadership. I believe that this is what happened to Benaud." In his next 23 Tests, Benaud attained the peak of proficiency - 131 wickets at 22.66 and 830 runs at 28.62, until a shoulder injury in May 1961 impaired his effectiveness.

Australia did not lose a series under Benaud's leadership, although he was defined by his deportment as much as his deeds. Usually bareheaded, and with shirt open as wide as propriety permitted, he was a colourful, communicative antidote to an austere, tight-lipped era. Jack Fingleton likened Benaud to Jean Borotra, the "Bounding Basque of Biarritz" over whom tennis audiences had swooned in the 1920s. Wisden settled for describing him as "the most popular captain of any overseas team to come to Great Britain".

One of Benaud's legacies is the demonstrative celebration of wickets and catches, which was a conspicuous aspect of his teams' communal spirit and is today de rigeur. Another is a string of astute, astringent books, including Way of Cricket (1960) and A Tale of Two Tests (1962), which are among the best books written by a cricketer during his career. "In public relations to benefit the game," Ray Robinson decided, "Benaud was so far ahead of his predecessors that race-glasses would have been needed to see who was at the head of the others."

Benaud's reputation as a gambling captain has probably been overstated. On the contrary he was tirelessly fastidious in his planning, endlessly solicitous of his players and inclusive in his decision-making. Benaud receives less credit than he deserves for intuiting that "11 heads are better than one" where captaincy is concerned; what is commonplace now was not so in his time. In some respects his management model paralleled the "human relations school" in organisational psychology, inspired by Douglas McGregor's The Human Side of Enterprise(1960). Certainly Benaud's theory that "cricketers are intelligent people and must be treated as such", and his belief in "an elastic but realistic sense of self-discipline" could be transliterations of McGregor to a sporting context.

Ian Meckiff defined Benaud as "a professional in an amateur era", a succinct formulation that may partly explain the ease with which he has assimilated the professional present. For if a quality distinguishes his commentary, it is that he calls the game he is watching, not one he once watched or played in. When Simon Katich was awarded his baggy green at Headingley in 2001, it was Benaud whom Steve Waugh invited to undertake the duty.

The forgotten legspinner © PA Photos

Benaud's progressive attitude to the game's commercialisation - sponsorship, TV, the one-day game - may also spring partly from his upbringing. In On Reflection he tells how his father, Lou, a gifted legspinner, had his cricket ambitions curtailed when he was posted to the country as a schoolteacher for 12 years. Benaud describes two vows his father took: "If… there were any sons in his family he would make sure they had a chance [to make a cricket career] and there would be no more schoolteachers in the Benaud family."

At an early stage of his first-class career, too, Benaud lost his job with an accounting firm that "couldn't afford to pay the six pounds a week which would have been my due". He criticised the poor rewards for the cricketers of his time, claiming they were "not substantial enough" and that "some players… made nothing out of tours". He contended as far back as 1960 that "cricket is now a business".

Those views obtained active expression when he aligned with World Series Cricket - it "ran alongside my ideas about Australian cricketers currently being paid far too little and having virtually no input into the game in Australia". Benaud's contribution to Kerry Packer's venture, both as consultant and commentator, was inestimable: to the organisation he brought cricket knowhow, to the product he applied a patina of respectability. Changes were wrought in cricket over two years that would have taken decades under the game's existing institutions, and Benaud was essentially their frontman.

In lending Packer his reputation Benaud ended up serving his own. John Arlott has been garlanded as the voice of cricket; Benaud is indisputably the face of it, in both hemispheres, over generations. If one was to be critical it may be that Benaud has been too much the apologist for modern cricket, too much the Dr Pangloss. It is, after all, difficult to act as an impartial critic of the entertainment package one is involved in selling.

Professionalism, meanwhile, has not been an unmixed blessing: what is match-fixing but professional sport in extremis, the cricketer selling his services to the highest bidder in the sporting free market? Yet Benaud is one of very few certifiably unique individuals in cricket history. From time to time one hears mooted "the next Benaud"; one also knows that this cannot be.

Benaud's progressive attitude to the game's commercialisation - sponsorship, TV, the one-day game - may also spring partly from his upbringing. In On Reflection he tells how his father, Lou, a gifted legspinner, had his cricket ambitions curtailed when he was posted to the country as a schoolteacher for 12 years. Benaud describes two vows his father took: "If… there were any sons in his family he would make sure they had a chance [to make a cricket career] and there would be no more schoolteachers in the Benaud family."

At an early stage of his first-class career, too, Benaud lost his job with an accounting firm that "couldn't afford to pay the six pounds a week which would have been my due". He criticised the poor rewards for the cricketers of his time, claiming they were "not substantial enough" and that "some players… made nothing out of tours". He contended as far back as 1960 that "cricket is now a business".

Those views obtained active expression when he aligned with World Series Cricket - it "ran alongside my ideas about Australian cricketers currently being paid far too little and having virtually no input into the game in Australia". Benaud's contribution to Kerry Packer's venture, both as consultant and commentator, was inestimable: to the organisation he brought cricket knowhow, to the product he applied a patina of respectability. Changes were wrought in cricket over two years that would have taken decades under the game's existing institutions, and Benaud was essentially their frontman.

In lending Packer his reputation Benaud ended up serving his own. John Arlott has been garlanded as the voice of cricket; Benaud is indisputably the face of it, in both hemispheres, over generations. If one was to be critical it may be that Benaud has been too much the apologist for modern cricket, too much the Dr Pangloss. It is, after all, difficult to act as an impartial critic of the entertainment package one is involved in selling.

Professionalism, meanwhile, has not been an unmixed blessing: what is match-fixing but professional sport in extremis, the cricketer selling his services to the highest bidder in the sporting free market? Yet Benaud is one of very few certifiably unique individuals in cricket history. From time to time one hears mooted "the next Benaud"; one also knows that this cannot be.

Benaud, the effort behind the effortless

His charismatic presence on and off the field has been well documented, but few, if any, speak of how hard he worked to achieve that

Daniel Brettig in Cricinfo

Expression serious, gaze intense, and concentration fixed - Richie Benaud is at work © Mark Ray

Expression serious, gaze intense, and concentration fixed - Richie Benaud is at work © Mark RayAmong countless images of Richie Benaud, both fluid and still, a most striking shot captures him away from the microphone, the television camera and the commentary box. It was taken by Mark Ray during a Perth Test match between Australia and England in 1991, and shows Benaud typing away fastidiously at a computer while his friend, pupil and fellow commentator Ian Chappell watches.

There is nothing mannered about the image, nor posed. Benaud's face does not bear the warm, wry expression that greeted television viewers the world over for more than 40 years. Instead, his expression is serious, his gaze intense and his concentration fixed. The beige jacket is hung up, and reading glasses sit on his nose. Maybe he is writing a column, maybe he is sending correspondence. Whatever the task, it is abundantly clear that Benaud is working.

Of the many and varied tributes that are flowing for Benaud, most speak of his charismatic presence both on the field as a captain and in the broadcast booth as a commentator. Most talk of his way with words, his mastery of when to use them, and more pointedly, when not to. Many say we will never see another like him, and that he was a unique gift to the game. Few, if any, speak enough of how hard he worked to be all these things.

Benaud was 26, and a four-year fringe dweller in the Australian Test side, when the 1956 Ashes tour concluded, England having kept the urn for a third consecutive series. Most of Ian Johnson's unhappy team-mates could not wait to get home, but Benaud stayed on after asking the BBC if he could take part in a course of television production and presenting. By that stage, he was already working as a police roundsman for The Sun in Sydney, chasing ambulances when he was not honing his slowly developing leg-breaks.

----------

Benaud's tips for aspiring commentators

Everyone should develop a distinctive style, but a few pieces of advice might be:

Put your brain into gear before opening your mouth.

Never say "we" if referring to a team.

Discipline is essential; fierce concentration is needed at all times.

Then try to avoid allowing past your lips: 'Of course'... 'As you can see on the screen'... 'You know...' or 'I tell you what'... 'That's a tragedy..." or "a disaster...". (The Titanic was a tragedy, the Ethiopian drought a disaster, but neither bears any relation to a dropped catch.)

Above all: when commentating, don't take yourself too seriously, and have fun.

--------

The broadcasting and journalism apprenticeship Benaud put himself through was exhaustive and exacting. He grew gradually in grasping the finer points of each trade, and would combine both when he stepped away from playing eight years later, having matured brilliantly as a cricketer and a captain. Cricket and leg-spin had taught Benaud about the level of commitment and perseverance required to succeed - as Bill Lawry has recalled, other players admired how Benaud emerged, not as a natural but a self-made man.

"I think the key to that for all of us was that he wasn't an immediate success," Lawry told The Age. "He worked very hard for four or five seasons, trying to establish himself in the Australian side. He went on one or two tours and hardly played a Test match. The fact he was so dedicated, he won through in the end."

When Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket emerged from its clandestine origins in 1977, Benaud's broadcasting apprenticeship paid off in much the same way as his cricketing one had done. More than 20 years of experience in broadcasting with the BBC and the ABC, among others, meant that he was not only Nine's host and lead commentator but also a sort of consulting producer, someone able to give direction to a crew ostensibly at the ground to direct him.

The polish of Nine's broadcast was there largely because Benaud had applied it himself, with the help of a gifted pair of brains behind the camera in David Hill and Brian Morelli. Having lived through the hectic earlier overnight shifts at The Sun and austere days learning the ropes at the BBC, broadcasting the cricket on Nine was a challenge well within Benaud's range - his unscripted introductions and summaries were as assured and comprehensive as those of the very best broadcasters.

If anything, he was too careful about expressing his opinions, a trait his more outspoken brother and fellow journalist John was never shy in offering a good-natured ribbing about. Nevertheless, Benaud's care with words reflected that he had learned much by spending time writing and speaking on the game. He knew the power of word and image, and made doubly sure he would be prepared enough to make the most of both.

Such dedication is commonplace among professional cricketers, and has become ever more so with each generation following on from the World Series Cricket revolution. But the path Benaud followed from playing into broadcasting has become the road less traveled, if at all. While so many within and without the game will say how much they loved and admired Benaud's work, precious few can be said to have made a genuine fist of following his example.

Chappell is one such figure, having worked assiduously at his writing down the years though never being trained formally as a journalist. Another, Mark Nicholas, traveled the world as a cricket correspondent for various publications including the Telegraph while still playing for Hampshire, and has clearly tried to take after Benaud as much as possible.

But it is a sad truth of 21st century cricket and its broadcasts that no one has truly held themselves to the standards that Benaud set for himself. Too few cricketers see themselves taking up a job in journalism or broadcasting until they can see the end of their playing career looming. Even if they do, it is generally understood that getting an "in" to the commentary box is more a matter of looking the part and having the right relationships than it is about training or aptitude. For that, the broadcasters themselves are as much to blame as the players.

So it is only to be hoped that the lessons of Benaud's life are made ever more indelible by the pain of his death. There will never be another Richie Benaud, but that does not mean that the game's players, writers and broadcasters cannot aspire to emulate him. It is not a matter of pulling on the beige jacket Benaud so often wore on the air, but of working as hard as he was in Ray's photo.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)