Yesterday at an outdoor coffee shop, I met my old friend James in person for the first time since the pandemic began. Over the past year on Zoom, he looked just fine, but in 3D there was no hiding how much weight he’d gained. As we sat down with our cappuccinos, I didn’t say a thing, but the first words out of his mouth were: “Yes, yes, I’m now 20lb too heavy and in pathetic shape. I need to diet and exercise, but I don’t want to talk about it!”

If you feel like James, you are in good company. With the end of the Covid-19 pandemic now plausibly in sight, 70% of Britons say they hope to eat a healthier diet, lose weight and exercise more. But how? Every year, millions of people vow to be more physically active, but the vast majority of these resolutions fail. We all know what happens. After a week or two of sticking to a new exercise regime we gradually slip back into old habits and then feel bad about ourselves.

Clearly, we need a new approach because the most common ways we promote exercise – medicalising and commercialising it – aren’t widely effective. The proof is in the pudding: most adults in high-income countries, such as the UK and US, don’t get the minimum of 150 minutes per week of physical activity recommended by most health professionals. Everyone knows exercise is healthy, but prescribing and selling it rarely works.

I think we can do better by looking beyond the weird world in which we live to consider how our ancestors as well as people in other cultures manage to be physically active. This kind of evolutionary anthropological perspective reveals 10 unhelpful myths about exercise. Rejecting them won’t transform you suddenly into an Olympic athlete, but they might help you turn over a new leaf without feeling bad about yourself.

Myth 1: It’s normal to exercise

Whenever you move to do anything, you’re engaging in physical activity. In contrast, exercise is voluntary physical activity undertaken for the sake of fitness. You may think exercise is normal, but it’s a very modern behaviour. Instead, for millions of years, humans were physically active for only two reasons: when it was necessary or rewarding. Necessary physical activities included getting food and doing other things to survive. Rewarding activities included playing, dancing or training to have fun or to develop skills. But no one in the stone age ever went for a five-mile jog to stave off decrepitude, or lifted weights whose sole purpose was to be lifted.

Myth 2: Avoiding exertion means you are lazy

Whenever I see an escalator next to a stairway, a little voice in my brain says, “Take the escalator.” Am I lazy? Although escalators didn’t exist in bygone days, that instinct is totally normal because physical activity costs calories that until recently were always in short supply (and still are for many people). When food is limited, every calorie spent on physical activity is a calorie not spent on other critical functions, such as maintaining our bodies, storing energy and reproducing. Because natural selection ultimately cares only about how many offspring we have, our hunter-gatherer ancestors evolved to avoid needless exertion – exercise – unless it was rewarding. So don’t feel bad about the natural instincts that are still with us. Instead, accept that they are normal and hard to overcome.

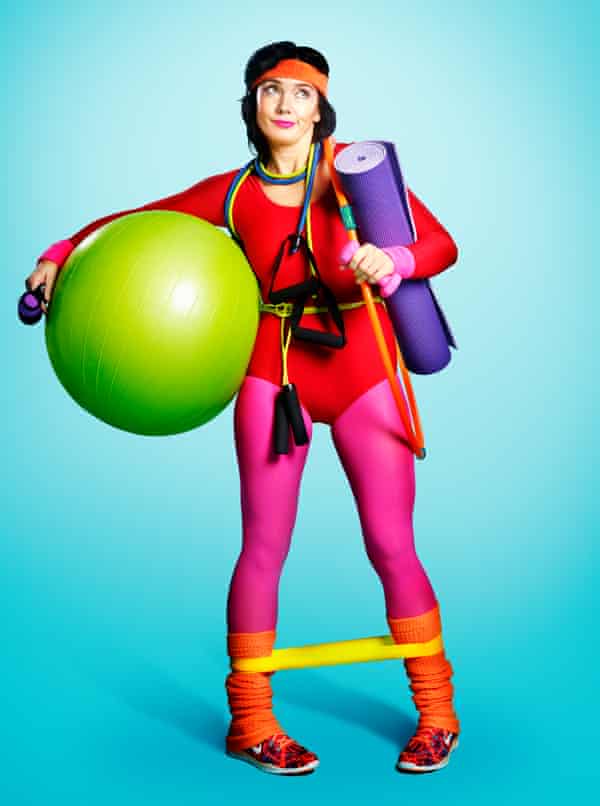

‘For most of us, telling us to “Just do it” doesn’t work’: exercise needs to feel rewarding as well as necessary. Photograph: Dan Saelinger/trunkarchive.com

Myth 3: Sitting is the new smoking

You’ve probably heard scary statistics that we sit too much and it’s killing us. Yes, too much physical inactivity is unhealthy, but let’s not demonise a behaviour as normal as sitting. People in every culture sit a lot. Even hunter-gatherers who lack furniture sit about 10 hours a day, as much as most westerners. But there are more and less healthy ways to sit. Studies show that people who sit actively by getting up every 10 or 15 minutes wake up their metabolisms and enjoy better long-term health than those who sit inertly for hours on end. In addition, leisure-time sitting is more strongly associated with negative health outcomes than work-time sitting. So if you work all day in a chair, get up regularly, fidget and try not to spend the rest of the day in a chair, too.

Myth 4: Our ancestors were hard-working, strong and fast

A common myth is that people uncontaminated by civilisation are incredible natural-born athletes who are super-strong, super-fast and able to run marathons easily. Not true. Most hunter-gatherers are reasonably fit, but they are only moderately strong and not especially fast. Their lives aren’t easy, but on average they spend only about two to three hours a day doing moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. It is neither normal nor necessary to be ultra-fit and ultra-strong.

Myth 5: You can’t lose weight walking

Until recently just about every weight-loss programme involved exercise. Recently, however, we keep hearing that we can’t lose weight from exercise because most workouts don’t burn that many calories and just make us hungry so we eat more. The truth is that you can lose more weight much faster through diet rather than exercise, especially moderate exercise such as 150 minutes a week of brisk walking. However, longer durations and higher intensities of exercise have been shown to promote gradual weight loss. Regular exercise also helps prevent weight gain or regain after diet. Every diet benefits from including exercise.

Myth 6: Running will wear out your knees

Many people are scared of running because they’re afraid it will ruin their knees. These worries aren’t totally unfounded since knees are indeed the most common location of runners’ injuries. But knees and other joints aren’t like a car’s shock absorbers that wear out with overuse. Instead, running, walking and other activities have been shown to keep knees healthy, and numerous high-quality studies show that runners are, if anything, less likely to develop knee osteoarthritis. The strategy to avoiding knee pain is to learn to run properly and train sensibly (which means not increasing your mileage by too much too quickly).

Myth 7: It’s normal to be less active as we age

After many decades of hard work, don’t you deserve to kick up your heels and take it easy in your golden years? Not so. Despite rumours that our ancestors’ life was nasty, brutish and short, hunter-gatherers who survive childhood typically live about seven decades, and they continue to work moderately as they age. The truth is we evolved to be grandparents in order to be active in order to provide food for our children and grandchildren. In turn, staying physically active as we age stimulates myriad repair and maintenance processes that keep our bodies humming. Numerous studies find that exercise is healthier the older we get.

Myth 8: There is an optimal dose/type of exercise

One consequence of medicalising exercise is that we prescribe it. But how much and what type? Many medical professionals follow the World Health Organisation’s recommendation of at least 150 minutes a week of moderate or 75 minutes a week of vigorous exercise for adults. In truth, this is an arbitrary prescription because how much to exercise depends on dozens of factors, such as your fitness, age, injury history and health concerns. Remember this: no matter how unfit you are, even a little exercise is better than none. Just an hour a week (eight minutes a day) can yield substantial dividends. If you can do more, that’s great, but very high doses yield no additional benefits. It’s also healthy to vary the kinds of exercise you do, and do regular strength training as you age.

Myth 9: ‘Just do it’ works

Let’s face it, most people don’t like exercise and have to overcome natural tendencies to avoid it. For most of us, telling us to “just do it” doesn’t work any better than telling a smoker or a substance abuser to “just say no!” To promote exercise, we typically prescribe it and sell it, but let’s remember that we evolved to be physically active for only two reasons: it was necessary or rewarding. So let’s find ways to do both: make it necessary and rewarding. Of the many ways to accomplish this, I think the best is to make exercise social. If you agree to meet friends to exercise regularly you’ll be obliged to show up, you’ll have fun and you’ll keep each other going.

Myth 10: Exercise is a magic bullet

Finally, let’s not oversell exercise as medicine. Although we never evolved to exercise, we did evolve to be physically active just as we evolved to drink water, breathe air and have friends. Thus, it’s the absence of physical activity that makes us more vulnerable to many illnesses, both physical and mental. In the modern, western world we no longer have to be physically active, so we invented exercise, but it is not a magic bullet that guarantees good health. Fortunately, just a little exercise can slow the rate at which you age and substantially reduce your chances of getting a wide range of diseases, especially as you age. It can also be fun – something we’ve all been missing during this dreadful pandemic.