Antidepressants are sometimes prescribed when they aren't needed, but never to use them is to miss an opportunity

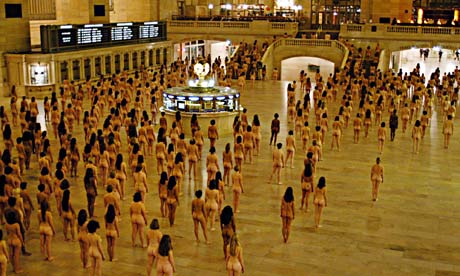

Antidepressants buy you time to sort out the issues that caused the depression in the first place. Photograph: Cultura/Rex Features

I can't stand zealots. Unfortunately, the literature on antidepressants is full of them. I'm not impressed by the protagonists in the polarised argument over the efficacy or otherwise of these drugs, whose positions are firmly held and loudly proclaimed. Many researchers appear to have written the conclusion of their study before the protocol.

At the one pole are the pharmaceutical industry and academic psychopharmacologists. I'll call them the pros. They urge us to practise only evidence-based medicine, by which they mean following rigid protocols based on treatments that have achieved positive results either in double-blind placebo-controlled drug trials, or meta-analyses (a method for grouping together results from several trials). Most of these studies focus on antidepressants because their effects are easy to measure.

The pros despise any practice not based on this narrow definition of evidence. One of them once told me: "Employing clinical experience to decide how to treat patients means continuing to make the same mistakes and never learning from them." So much for the lessons I've learned from treating about 3,000 people with this illness.

At the other pole are a group of naysayers who assert that antidepressants don't work any better than placebo. I'll call them the cons. They use the available statistics in the way best suited to their argument and are equally dismissive of any contrary view.

It's part of our culture to take up polarised positions. Our political and legal systems are based on this premise and our media rely on it. The middle ground isn't interesting and is rarely aired. It is this environment in which the pros and cons dominate the literature on antidepressants. Meanwhile, sufferers from the depressive illness don't know which way to turn.

The root of the problem is that good research is difficult and limited. Research is good at showing big effects in large groups of people. It's not so good at showing more subtle, or difficult to define, effects in subgroups of people. The results of your study will depend on whom you study, what you measure, what you define as an effect and what you do with your data.

The cons say that the pros have suppressed some findings that didn't suit them. If you compare two identical groups 20 times, you will find an apparently significant difference between them once. Test your ineffective antidepressant 20 times and you'll be able to publish a positive result, so long as you suppress the other 19. We clinicians knew this was happening years ago. One particular antidepressant was known by everyone to lack efficacy, yet the studies appeared to show that it worked as well as all the rest. Something was wrong with the published research and it seems we may now know what it was. Recent research seems to under-report some side-effects and withdrawal effects of antidepressants.

The cons are equally selective. They point to meta-analyses showing that antidepressants don't out-perform placebo sufficiently to reach this arbitrary level of significance. They conclude that antidepressants don't work. This is the oldest misuse of statistics in the book. An insignificant difference doesn't mean that you've proven no difference; it just means that you haven't proved that there is one.

Another issue is failing to exclude the outlier. As I've already pointed out, one expects occasional misleading results from research. A meta-analysis should deal with this problem by excluding from the analysis any study with results wildly different from all the others. The pros say that this hasn't always happened in the cons' analyses, potentially producing misleadingly negative results.

So research is failing us in this field. Unfashionable though this is in the environment currently existing in medicine, it means we clinicians need to use our experience, powers of observation and common sense, bearing in mind the experience of other clinicians.

We need to take note of the available research, while also taking a critical view of it. Here is the upshot, accepted by most of us on the ground: antidepressants usually work, but only for real clinical depression, the type involving a chemical disturbance in the brain, with a full range of characteristic physical symptoms. They don't work for unhappiness, grief or chemically induced depression and if you take them irregularly or for too short a period, the depression comes back.

Prescription numbers are rising mainly because doctors are getting better at identifying depression, though antidepressants are sometimes prescribed when they aren't needed and won't work. Except for people suffering from recurrent depression they are only first aid, buying you time to sort out the issues that caused the depression in the first place, but never to use them is to miss an opportunity to provide relief from this horrible illness.

Dr Tim Cantopher, consultant psychiatrist, Priory Hospitals Group, author of Depressive Illness – the Curse of the Strong (Sheldon)

22 Comments

22 Comments