Property developers wining and dining town hall executives - it’s a jaunt so lavish as to be almost comic

Starting this Wednesday, 4,000 men (and, yes, they’ll mainly be men) will gather in a giant hall in London. Among them will be major property developers, billionaire investors and officials of your local council or one nearby. And what they’ll discuss will be the sale of public real estate, prime land already owned by you and me, to the private sector. The marketing people brand this a property trade show, but let’s drop the euphemisms and call it the sales fair to flog off Britain.

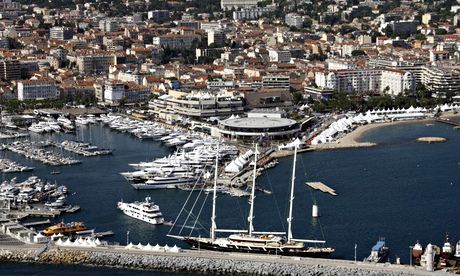

For the past 25 years, this conference – Mipim for short – has been held in Cannes. It’s a jaunt so lavish as to be almost comic – where big money developers invite town hall executives for secret discussions aboard private yachts, and whose regulars boast that they get through more champagne than all the liggers at the film festival.

Suitably oiled-up, local officials open talks with multinational developers to sell council housing estates and other sites. All this networking is so lucrative for the builders that they even fly over council staff. Last year, Australia’s Lend Lease paid for Southwark’s boss, Peter John, to attend Cannes. This is the same Lend Lease to which Southwark sold the giant Heygate estate at a knockdown price: 1,100 council flats in inner London to be demolished and replaced with 2,500 units, of which only 79 will be for “social rent”.

Events such as Mipim raise the flag on the land grab that eventually leads to thousands of people being kicked out of their homes – and in many cases out of London. It is a forum that relies on invitation-only lunches, secret talks and the public being kept well away. In a shamefully undemocratic development system, this is one of the most untransparent forums of the lot.

You might think that seven years after the collapse of an economic system built on property speculation and amid a historic housing crisis, Mipim would have no place in the UK. You’d be wrong. When it opens this week it will be to a welcome address from that loveable friend of big money, Boris Johnson. Even with 344,000 households in London awaiting a council home, the mayor is cheering on their flogging off and replacement with unaffordable luxury flats. Joining him will be Conservative ministers, senior civil servants and council delegations from Glasgow through Leeds and Liverpool and down to Croydon.

Many of these councils are coming because they have no other means of raising serious cash: three decades after Thatcher’s rate caps, and four years into the most painful cuts faced by local government, they are flat broke. Some council leaders will admit as much privately. But in all cases, the strong scent of neediness comes off their planned Mipim session titles (“Croydon: the economic powerhouse of the south-east”) – and forces them into the kind of rotten deals that jeopardise the livelihoods of their residents.

On Sunday afternoon, a group of about 40 Londoners convened in a Pimlico community centre. A greater contrast with the hangars of Mipim can hardly be imagined: no lavish buffet, just a kettle and some instant coffee; no PowerPoint slides but a dungareed bloke scribbling on a flipchart. But the people here knew about the property fest: they live on the council estates about to be demolished to make way for private developers. They reeled off where they were from: Chelsea, Elephant and Castle, Haringey, Barnet. Some had already been handed their court orders and were unsure if they’d even be in London next month. One woman, who had bought her Southwark council flat as Thatcher and Blair encouraged her to, had been offered a risible sum to get out. As the group planned meetings and demonstrations before Christmas, she kept repeating: “I might be homeless by then.” The first couple of times, she even managed to smile.

These people live in public housing built with public money on public land. And soon, their homes will be someone else’s speculative asset. The British Property Federation (BPF) published a report last year which showed that of London’s newly built homes, only 39% were bought to live in. The vast majority – 61% – were taken by investors. After the meeting broke up, a resident of Churchill Gardens in Pimlico walked me around her estate and pointed out the old people’s home and lovely modernist low-rise block that was earmarked for the wrecking ball. It faced out on to the Thames; on the other side was Battersea power station, being turned by Malaysian investors into luxury flats. In this part of London, that same BPF report found, 49% of new-build homes were bought by overseas investors.

Against that backdrop even the smallest victory looks historic. Up on the northwestern perimeter of London, in West Hendon, other council residents are fighting the borough of Barnet over the redevelopment of their estate on terms that suit the developer, Barratt Developments, not locals. Just under 700 homes are to be smashed up to make way for 2,000 new units. Just under 1,500 will be sold privately: the rest will be “affordable”, which in the doublespeak of housing means unaffordable.

The council cannot say how many social-rental homes will be provided, but it is clear that whatever provision there is will be grudging. With a quick Google you’ll find a video of the chair of Barnet’s housing committee, Tom Davey, claiming that his council is providing affordable housing because people are buying them. An objector points out that only the wealthy can afford them and the young Conservative thumps the desk and says: “Those are the people we want.”

Whatever the propaganda, when I turn up at West Hendon, I meet a telecoms worker and a full-time carer. I also meet a woman in her 60s who hasn’t had a good night’s sleep in years, and a man facing homelessness and suffering depression.

About a third of the estate’s residents have already been bounced from regeneration to regeneration. They have no idea where they’ll go when they’re moved out. Others are leaseholders who can’t afford to buy anywhere in London on the £165,000 offered by the council. The majority of the tenants will be moved to what was formerly a car park, surrounded by busy roads.

“A giant traffic island” is how it is described by Jasmin Parsons, who’s lived on the estate for over 30 years. From there, she and her neighbours can look at their old homes, which are now off-limits to them and their children. Their faces won’t fit the area, you see, and their bank balances certainly don’t go far enough. They’ll be barely tolerated trespassers on yet another private development.

Maybe there’s a metaphor in there for all of us.