'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label airport. Show all posts

Showing posts with label airport. Show all posts

Thursday, 2 March 2023

Thursday, 20 February 2014

Why Mumbai's new air terminal has gone off the rails

Sharing the name Chhatrapati Shivaji, the airport and train terminus have much in common: both were once the future

- Naresh Fernandes in Mumbai

- theguardian.com,

The new terminal 2 at Chhatrapati Shivaji international airport, in Mumbai. Photograph: Punit Paranjpe/AFP/Getty Images

The long-awaited airport terminal at Mumbai's Chhatrapati Shivaji airport finally opened its aerobridges and check-in counters to passengers this month. In the buildup, any number of journalists had been led on tours through the new facility, and I'd absorbed their reports with a mixture of awe and amusement. The new terminal – the T2 – has 5,000 square metres of landscaping, I learned, and 21,000 square metres of retail space for luxury shops. Some reports also noted that the terminal, which will serve about 40 million passengers each year, will have access to 101 toilet blocks.

In Mumbai, nativists have ensured that almost every new building is named after the 17th-century warrior-king Shivaji, and as I read about the splendours of the new terminal at Chhatrapati Shivaji, I couldn't help thinking about another Chhatrapati Shivaji terminus across town – a hyperkinetic railway station that used to be known as the Victoria terminus.

That terminus is used by 3.75 million people every day, which means it gets as many visitors in 11 days as the terminal at the airport terminal has in a year. But the rail travellers only have access to 83 toilets and urinals – not toilet complexes like the air passengers have, but 83 individual toilets.

When it was opened more than a century ago, however, the Chhatrapati Shivaji railway terminus, which bears an uncanny resemblance to London's St Pancras, was the T2 of its time. It featured state-of-the-art everything, even state-of-the-art art. Its impressive stone façade is alive with sculptures of gargoyles and squirrels and flying birds that were executed under the guidance of Lockwood Kipling, the principal of the JJ School of Art down the road (his son, Rudyard, would grow up to become poet laureate of the empire).

People on a platform inside Chhatrapati Shivaji terminus, previously known as Victoria terminus, railway station in Mumbai. Photograph: David Pearson/Rex

People on a platform inside Chhatrapati Shivaji terminus, previously known as Victoria terminus, railway station in Mumbai. Photograph: David Pearson/Rex

The new terminal at Mumbai's airport also features a profusion of artworks. Press reports say that more than 7,000 exhibits have been assembled, some by contemporary artists and others from across the ages, reaching back to the 6th century. In fact, the airport website describes the T2 display as "India's largest public art programme". The curator of the collection, Rajeev Sethi, told The New York Times: "The concept of art in public space is a very serious issue because art cannot shrivel up and shrink into investment portfolios or disappear into godowns [warehouses] or galleries. It has to be in the public domain."

The difference between the two terminuses demonstrates just what's going wrong with Mumbai. After two decades of economic liberalisation, its middle class has been so brainwashed into believing privatisation is the solution for all their problems that the city seems to have forgotten what public actually means. As art historian Rahul D'Souza points out: "Richer residents are quite willing to accept the idea that an art exhibition can be public, even if it can accessed only by people who have bought an international air ticket." This attitude will surely have a profound effect on Mumbai's politics in the near future.

The middle-class aspiration for exclusivity is a jarring disjuncture with the mythology and history of a city that lives the best part of its life in full view of its neighbours, with one of the highest population densities in the world (it packs 22,937 people into each square kilometre, compared to 5,285 people in London). The size of the average Mumbai family is 4.5 people, and the average home size is 10 square metres, so some of their most private moments transpire in the midst of a crowd.

Much of Mumbai's easy urbanity has been forged in the sweaty confines of its public transport system, by far the most extensive in India. In its compartments, people of different castes and communities are forced to share benches and be wedged together in positions of daring intimacy. This is only to be expected when 5,000 commuters are stuffed into trains built to carry 1,800 – a density that the authorities describe as the "super-dense crushload". The commonplace negotiations of the commute – such as the convention of allowing a fourth traveller to sit on a bench built for three, but only on one buttock – force an acknowledgement of other people's needs that characterises Mumbai life.

A woman looks at artwork on display at terminal 2 at Chhatrapati Shivaji airport. The new terminal holds around 7,000 works of art. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

A woman looks at artwork on display at terminal 2 at Chhatrapati Shivaji airport. The new terminal holds around 7,000 works of art. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

The Mumbai commute, in addition to being compacted, is very long – for some, it could involve a journey of two hours each way. This has given rise to the institution of "train friends", people who travel in a group in the same section of the same compartment every morning, sharing stories of their triumphs and disappointments and even celebrating their birthdays by bringing in sweets for their companions.

Despite the enormous effort they sometimes entail, the accommodations of the commute are barely perceptible to the outsider. Because of the unavoidable press of bodies at peak hours, women travel in separate carriages – but every so often, couples who cannot bear to be parted or a clueless out-of-town pair will blunder into the "general compartment". When this happens, the other men will strain to provide the woman a millimetre or two of space around her, creating a cocoon in which she is magically insulated from the accidental nudge of limbs and torsos.

This isn't to suggest that life on the rails is all smiles and sunshine. As is to be expected on a long, sweaty journey, arguments do break out, mostly over trivial matters involving the placement of a limb or a bag in awkward proximity to a fellow passenger's face. But these exchanges rarely culminate in fisticuffs. The crowd around the belligerents can be counted on to defuse the tension quickly, usually with the remark, "These things happen. You have to adjust".

Sadly, though, the spirit of compromise so evident on the trains is evaporating on the streets outside. To watch Mumbai traffic in motion is to see the ferocious sense of entitlement in which India's moneyed classes have wrapped themselves. Mumbai's vehicles refuse to give way to ambulances, and honk furiously at old people and schoolchildren trying to cross the street. They never stop at zebra crossings, frequently jump red lights, and routinely come down the wrong way on no-entry streets. Because an estimated 60% of cars are driven by chauffers, more than in most other parts of the world, car owners have the fig-leaf of pretending that they aren't responsible for transgressions they actually encourage. And this sense of self-importance is pandered to by the government's budgetary allocations. Though the vast majority of Mumbai residents use the overburdened public transport system to get around, a disproportionate amount of development money has been poured into road projects.

Female commuters wait to cram into a ladies only carriage on a rush hour train from Chhatrapati Shivaji rail terminus. The trains were designed to carry around 1,800 passengers, and currently hold around 5,000 per journey. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

Female commuters wait to cram into a ladies only carriage on a rush hour train from Chhatrapati Shivaji rail terminus. The trains were designed to carry around 1,800 passengers, and currently hold around 5,000 per journey. Photograph: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters

The city has built approximately 60 flyovers and elevated roadways in recent years – facilities that have paradoxically made the congestion on the roads far worse. As incomes expand, traffic is growing at a rate of 9% a year, with an estimated 450 new vehicles being added to Mumbai's narrow streets every day. As a result, peak-hour traffic crawls ahead at an average of 10kmh – less than half the speed clocked by winners of the city's annual marathon. It merely proves the adage so beloved of planners around the world: "Building more roads to prevent traffic congestion is like a fat man loosening his belt to prevent obesity."

The imbalance so apparent between Mumbai's transport system and its airport seem sure to polarise political attitudes in the city even more sharply. The city's middle classes have become so enamoured of their privatised comforts, they are forgetting that great cities get their reputation not from the access-restricted pleasures they afford the few, but the public amenities that are available to all. The chasm between the elite and the working classes has long been the playground for populist politicians, here and elsewhere. But over the last few years, such divisions in Mumbai have literally been reinforced by concrete. Unless this changes, my city will lose the common ground on which to make common cause.

Thursday, 16 May 2013

How Nawaz Sharif beat Imran Khan .....

The results of the Pakistan elections are in – but how did a former exile win the vote? By promising airports to people who can't afford bicycles, says novelist Mohammed Hanif

Here's a little fairytale from Pakistan. Fourteen years ago a wise man ruled the country. He enjoyed the support of his people. But some of his treacherous generals thought he wasn't that smart. One night he was held at gunpoint, handcuffed, put in a dark dungeon, sentenced to life imprisonment. But then a little miracle happened; he, along with his family and servants, was put on a royal plane and exiled to Saudi Arabia, that fancy retirement home for the world's unwanted Muslim leaders.

Two days ago that same man stood on a balcony in Lahore, thanked Allah and said: Nawaz Sharif forgives them all.

But wait, if it was a real fairytale, Imran Khan would have won the election instead, right? Can't Pakistani voters tell between a world-famous, world cup-winning, charismatic leaderand a mere politician who refers to himself in the third person?

Why didn't Imran Khan win?

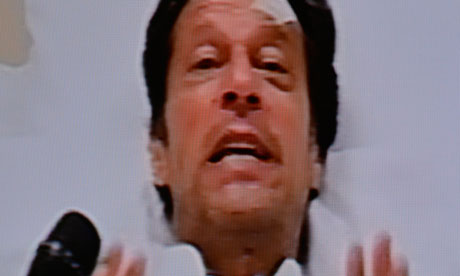

Imran Khan in hospital after a fall at a campaign rally. Photograph: HO/AFP

Imran Khan in hospital after a fall at a campaign rally. Photograph: HO/AFP

Well he has, sort of. But not in the way he would have liked. Visiting foreign journalists have profiled Imran Khan more than they have profiled any living thing in this part of the world. If all the world's magazine editors were allowed to vote for Imran Khan he would be the prime minister of half the English-speaking world. If Imran Khan had contested in west London he would have won hands-down. But since this is Pakistan, he has won in Peshawar and two other cities. His party is set to form a government in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, that north-western frontier province of Pakistan which Khan's profile writers never fail to remind us is the province that borders Afghanistan and the tribal areas that the world is so scared of. Or as some others never fail to remind the world: the land of the fierce pathans.

It's true that Khan ran a fierce, bloody-minded campaign, drawing huge crowds. When his campaign culminated in a televised tumble from a stage, during a public rally, the whole nation held its breath. Khan galvanised not only Pakistan's parasitical upper classes but also found support among the country's young men and women of all ages; basically the kind of people who use the words politics and politician as common insults. He inspired drawing-room revolutionaries to go out and stand in the blistering heat for hours on end to vote for him. For a few months he made politics hip in Pakistan. Partly, he was relying on votes from Pakistan's posh locales. He probably forgot that there was a slight problem there: not enough posh locales in Pakistan. There were kids who flew in from Chicago, from Birmingham to vote for him. Again, there are not enough Pakistani kids living and studying in Chicago and Birmingham. He appealed to the educated middle classes but Pakistan's main problem is that there aren't enough educated urban middle-class citizens in the country.

And the masses, it appears, were not really clamouring for a revolution but for electricity.

From the gossip columns of British tabloids to massive political rallies across Pakistan, Khan has been on a meaningful journey. In his campaign speeches, his blatantly Blairite message of New Pakistan did appeal to people but he really tested his supporters' attention span when he started to lecture them about how the Scandinavian welfare state model is borrowed from the early days of the Islamic empire in Arabia. Amateur historians have never fared well in Pakistani politics. Or anywhere else. Khan promised to turn Pakistan into Sweden, Norway or any one of those countries where everyone is blond and pays tax. His opponents promised Dubai – where everyone is either a bonded labourer or a property speculator and no one pays taxes – and won.

It's a bit of a fairytale that Khan, whose message was directed at educated urban voters, has found supporters in the north-western frontier province that profile writers must remind us is largely tribal and the front line of the world's war on terror. Khan has led a popular campaign against drone attacks. He has promised that he will shoot down drones, look Americans in the eye, sit down with the Taliban over a cup of qahwa and sort this mess out.

So we finally have someone who feels at home in Mayfair as well as Peshawar. He finally has the chance to rule Peshawar. Slight problem: as he speaks no Pashto, the language of the Pathans. But his first fight will be against American drones hovering in the sky. And drones speak no Pashto either. If Khan can win this match, he can challenge Nawaz Sharif in the next elections.

Is this Nawaz Sharif man for real?

Nawaz Sharif at a campaign rally in Liaquat Bagh, Pakistan. Photograph: T. MUGHAL/EPA

Nawaz Sharif at a campaign rally in Liaquat Bagh, Pakistan. Photograph: T. MUGHAL/EPAHasn't he been tried before? Twice? It seems voters in the largest province of Pakistani Punjab just can't have enough of this guy. At every campaign stop, Sharif reminded his supporters of two of his biggest achievements: I built the motorway, I built the bomb. He did build Pakistan's first motorway. And despite several phone calls from the then American president Bill Clinton and other world leaders and offers of million of dollars in aid, Sharif did go ahead and order six nuclear explosions in response to India's five. And then he thought that now that both countries have the bomb he could go ahead and be friends with India. While he was making history hosting the Indian prime minister in the historic city of Lahore, his generals were busy elsewhere repeating history on the mountains of Kargil. In a misadventure typical of Pakistani generals, they occupied the abandoned posts and then pretended that these were mujahideen fighting India and not regular Pakistan army soldiers.

When India reacted with overwhelming force and a diplomatic offensive, Sharif pleaded ignorance and rushed off to Washington to bail out the army and his own government. President Clinton praised his diplomatic skills and the crisis was resolved briefly. When, months later he tried to fire his handpicked army chief General Pervez Musharraf, the architect of the Kargil fiasco, a bunch of army officers put their guns to Sharif's head. Handcuffed, jailed, sentenced to life imprisonment, in the end Sharif was saved by his powerful friends in Saudi Arabia. A royal jet flew him, his family and his servants to a palace in Saudi Arabia. An exile in Saudi Arabia for Muslim rulers is generally considered a permanent retirement home where you get closer to Allah and atone for past sins. Sharif must be the only politician in exile in Saudi Arabia who not only managed to survive this holy exile but in the process got a hair transplant and managed to hold on to his political base in Pakistan.

Many of his political opponents say that if Sharif wasn't from the dominant province Punjab, where most of the army elite comes from, if he didn't represent the trading and business classes of Punjab, he would still be begging forgiveness for his sins in Saudi. But he returned just before the last elections and has been behaving like a statesman. A very rich statesman.

It has yet to be proven whether eight years of exile in Saudi Arabia can make anyone wiser but it has never made anybody poorer. Sharif was rich before he got into politics, then he became fabulously rich. Even in exile the Saudis gave him a palace and, on his return, a fleet of bulletproof limousines. His campaign proved that poor people don't really vote for somebody who understands poverty, or wants to do anything about it. People have voted him in because he talks money, talks about spending money, talks about opening a bank on every village street and who doesn't like that? He has promised motorway connections and airports to towns so small that they still don't have a proper bus station. Poor people, who couldn't afford a bicycle at the time of the elections, like to be promised an airport. You never know when you might need it.

In his five years' rule in Punjab, Sharif's party has had one policy about the Pakistani Taliban who have been wreaking havoc in parts of Pakistan: please go and do your business elsewhere. And they have generally obliged. But now that he is set to rule all of Pakistan, what's he going to tell them?

Have we defeated the Taliban or sent them a friend request?

A voter displays her inked thumb after marking her ballot paper at a polling station in Karachi. Photograph: Athar Hussain/REUTERS

A voter displays her inked thumb after marking her ballot paper at a polling station in Karachi. Photograph: Athar Hussain/REUTERS

When Pakistan decided to throw itself an election party, the first ones to arrive were the Taliban. They weren't really interested in the party because they keep reminding us that elections are un-Islamic and a major sin on a par with educating girls. But they were interested in watching what party games were played and who got to play them. They decided that the three political parties that had ruled Pakistan for the past five years and taken a clear stand against the Taliban would be targeted. And the Taliban started their own campaign, targeting candidates and their supporters with bomb attacks and drive-by shootings. In one case, a candidate in Karachi was shot as he came out of a mosque. Along with his six-year-old son. The election campaign across Pakistan looked like this: some parties held huge rallies, in a carnival-type atmosphere with live tigers and massive music systems. Other candidates sneaked from one little corner meeting to another trying to remind people of their heroic stand against the Taliban. Many of the candidates were never seen in public. Many journalists refused to visit them because they were sitting targets. Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, the public face of the ruling People's party, could only deliver a couple of video messages from Dubai.

The other parties, the ones who were allowed to campaign freely, were grateful in their silence. When we look at the election results we must not forget that while the Pakistani Taliban didn't contest the elections as a political party, they did see themselves as kingmakers. In Pakistan's liberal media the Taliban are often described as brutes with an endless bloodlust. But by making allies and choosing partners they have demonstrated that they are at least as canny as the average campaigning politician.

But in the end the Taliban failed to deliver the kind of devastation they had promised. They managed to kill about 130 people in eight weeks. In the past they have achieved that kind of number in a single day. Also, 60% of Pakistanis who came out to vote seem to be politely disagreeing with the Taliban by saying that there is nothing un-Islamic about standing in a queue and stamping a ballot paper.

The Taliban's real success is that they bet on the winners. They promised not to attack Khan and Sharif's parties. And these parties will be in power. But the Taliban have never contested an election before. And they are soon to find out that politicians never keep the promises they make during the heat of the campaign.

Why does this election mean nothing for Farzana Majeed?

Pakistani voters line up at a polling station in Karachi. Photograph: Athar Hussain/Reuters

Pakistani voters line up at a polling station in Karachi. Photograph: Athar Hussain/Reuters

Three weeks before the elections, a 27-year-old biochemistry graduate stood outside Karachi Press club. Farzana Majeed and a couple of dozen young people carried pictures of Zakir Majeed, a literature student who was abducted by Pakistan's military intelligence four years ago and since then has become one of the hundreds of missing Baloch people, mostly young, political activists. Their mutilated, tortured bodies turn up on the roadsidewith sickening regularity. The Pakistani media, otherwise quite noisy about every subject under the sun, stay quiet. None of the political parties campaigning in recent elections uttered a word about Zakir Majeed or hundreds of other people languishing in military-run dungeons. Why? Because it's a security issue. A militant separatist movement in parts of Balochistan means that the rest of Pakistan sees it as an enemy. The protesters distributed pamphlets encouraging the fellow Balochs not to participate in the elections. The voter turn out in Baloch areas in Balochistan has been less than 10%. No political party in the country had the heart to go and ask Farzana Majeed or thousands of other families to vote. Farzana is a polite, articulate person but mention the word elections and she is likely to wave her missing brother's picture in front of you. And just like Pakistan's last political government, the new one also doesn't want to see this picture.

So what happens to the federation?

Watching the election results come in, in a teashop in Lahore. Photograph: Damir Sagolj/REUTERS

Watching the election results come in, in a teashop in Lahore. Photograph: Damir Sagolj/REUTERS

Who needs a federation when you can have so much more fun doing things your own way. So in the post-election Pakistan, Khan will rule the north and shoot down American drones while discussing Scandinavian social welfare models with the Taliban. Sharif will rule in Punjab and the centre, try to do business with India and build more motorways all the while looking over his shoulder for generals looking at him. In the south, Bhutto's decimated People's party will keep ruling and keep saying that folks up north are stealing its water, destroying its social welfare programmes and secular legacy. And, in Balochistan, Farzana Majeed will keep waving her missing brother's picture.

Do these bits add up to a country? They do, if you are sitting in Islamabad and showing off your nuclear weapons to the world or planning a motorway to central Asia. But if you are an old woman waiting for her 2,000-rupee welfare cheque or a student activist in a military dungeon waiting for your next interrogation session, you are not likely to dream of motorways and new airports.

Pakistan as a federation has gone through its first rite of passage: handover of power from one elected civilian setup to another. It took Pakistan 67 years to get here. Let us not forget that the reasons that caused this delay haven't disappeared.

Mohammed Hanif is BBC Urdu's special correspondent based in Karachi. He is the author of A Case of Exploding Mangoes and Our Lady of Alice Bhatti

Monday, 16 April 2012

Civil Aviation in India

India mulls over 49% overseas share in airlinesBy Raja Murthy

MUMBAI - The Indian government on April 12 postponed to this week an eagerly awaited decision to allow foreign airlines own up to 49% stake in Indian carriers. But overseas funding alone is unlikely to rescue India’s struggling US$12 billion civil aviation industry.

It's more a case of mismanaged potential that has caused five out of the six Indian carriers, except Indigo, to have accumulated losses of nearly $2 billion in the past two years. India, the world's ninth largest civil aviation market, had passenger traffic doubling

India aims to be among the world's top three aviation markets within a decade. In between are mountains to climb and some strange oddities to correct - such as building multi-billion dollar luxury airports in an industry dominated by low-cost airlines.

The foreign direct investment (FDI) move, if it materializes as part of the mountain climbing process, could give desperately needed survival cash and breathing time to nearly dead flying companies like Kingfisher Airlines. The Vijay Mallya-promoted carrier is drowning in a debt of $1.3 billion, with no new loans forthcoming, with over 60% of its aircraft fleet grounded and its employees receiving salaries for December 2011 only on April 9.

The state-owned carrier Air India has similar mismanagement woes, but continues to receive public money to bankroll it. On April 12, the government approved 300 billion rupees (US$5.7 billion) as bailout and part of a revival plan for Air India across the next eight years. This after Civil Aviation minister Ajit Singh informed parliament that Air India incurs losses of $1.9 million every day, or over $700 million annually.

Whether Air India would fare better without government ownership is as moot a question as whether more funding, including FDI, could only be more investment down the drain. Waiting to be surgically treated are roots of the problem such as unviable operating costs for airlines.

Unfairly high taxes on aviation fuel have long been a major complaint for India's airline industry. Aviation Turbine Fuel (ATF) continues to be over 50% costlier in India than in Singapore and Malaysia. Fuel costs contribute about 45% of the operational costs of India's airlines.

Yet India's state-owned oil companies sell jet fuel cheaper to international airlines than for domestic flights in Indian airports. Indian Oil, for instance, sells jet fuel at $1,010 per kilo liter for international airlines in Mumbai (March 1, 2012 prices), while domestic airlines pay a pre-tax cost of $1,316.77. International airlines are free from sales tax on aviation fuel, while domestic airlines pay an additional 26% sales tax that local state governments levy.

Instead of the obvious step of reducing aviation fuel taxes to reasonable levels - or to only at least 25% above international levels - the Indian government earlier this year allowed domestic airlines to directly import aviation fuel. That seems as bizarre as asking an impoverished dying patient to go overseas to buy medicine available down the street.

Even more peculiar is that India exports nearly half its production of aviation fuel. According to Ministry of Petroleum data, India exported 4.478 million tonnes of aviation fuel in 2010-2011, out of total aviation fuel production of 9.570 million tonnes,

Fuel costs are only part of the problem. Aviation infrastructure growth appears heading in a direction different from requirements for industry growth. Privatization of metropolitan airports, for instance, resulted in multi-billion dollar upgrades for the Mumbai and Delhi airports, and new airports for Bangalore and Hyderabad. The impressive new airports though are driving up operational costs for a budget airline industry that critically needs low-cost infrastructure.

The spectacular new Terminal 3 of New Delhi's is itself both solution and problem. Built and operated by the Delhi International Airport (P) Ltd (DIAL) - a joint venture consortium of global infrastructure company GMR Group, Airports Authority of India, Fraport and Malaysia Airports Holdings Berhad - Terminal 3 makes Indira Gandhi International Airport (IGI) one of Asia's largest public buildings and the world's second-largest integrated airport, after Beijing Capital International Airport.

The $6 billion Terminal 3, spread along 4 kilometers and with a roof area of 45 acres (18.2 hectares), serves as future investment for Delhi having the world's fastest growing airport passenger traffic. According to the Montreal-based Airport Councils International, Delhi registered passenger traffic growth of 21.77%, faster than Jakarta's 19.2% and Bangkok's 12% growth. This compares impressively to the 1.8% air passenger traffic growth in North America.

But India's airlines and passengers are being asked to pay more airport fees and taxes to recover the multi-billion dollar costs for the new airports. Both Air India and Kingfisher Airlines alone owe the Delhi airport $100.4 million in airport fees. So airport employees are also suffering salary delays.

International carriers are too feeling the pinch. Malaysia's Air Asia, the continent's leading budget airline, announced termination of its flights out of the Delhi and Mumbai airports from March 24 this year, citing excessively high airport and handling fees and aviation fuel costs at these airports. Air Asia continues to fly from five other cities in South India.

The Airports Economic Regulatory Authority has proposed a 280% increase in landing and parking charges at Delhi airport, while the airport operator DIAL wants a 700% increase. Not just low-cost airlines, but Lufthansa, Air France, KLM and British Airways have announced putting on hold expansion plans in India due to the huge hike in operational fees at IGI Terminal 3.

Such headaches were not quite anticipated when an Air Deccan 48-seater ATR turbo-prop aircraft took off from Hyderabad to Vijayawada on September 26, 2003, to unofficially launch low-cost airlines in India. Since then, a heavily loss-making Air Deccan was bought by Kingfisher in 2007, and now a heavily loss-making Kingfisher is looking to sell itself to a foreign carrier.

The pending 49% FDI decision on the governmental anvil is actually a throwback to over six decades ago. In 1951, the government bought a 49% stake in Air India, founded and owned by the Tata Group. The government retained an option to buy another 2% stake and became owner. It did so under the Air Corporations Act of 25 August 1953 that nationalized all private airlines.

Air travel was booming in India in the 1950s, with cheaply available World War II surplus aircraft and India having bountiful skilled air pilots and maintenance crews after the war. The 26-page "Official Airline Guide" of July 1952, published by the Air Transport Association of India, lists schedules for about nine domestic airlines: Air India Ltd (also called The Tata Airline), the Air Services of India (also called the Scindia Airline), Airways (India) Ltd, Bharat Airways (also called the Birla Airline), Deccan Airways, Himalayan Aviation, the Indian National Airways, Kalinga Airlines and Air India International.

In 1953, India had over 20 private airlines, with unstructured growth without proper infrastructure creating market problems similar to the current woes of some domestic airlines. JRD Tata (1904-1993), called the father of civil aviation in the subcontinent, predicated an industry disaster. One of the reasons why the government nationalized the entire airline industry in 1953 was apparently to ward off many private airlines going bankrupt.

Now with Air India saved from bankruptcy with a $5.7 billion gift of public money, the government may as well consider re-privatizing Air India, and selling 49% of the stock back to its original owners the Tata Group.

The $5.7 billion bailout and the 49% FDI decision for overseas investors have better chances of working only if the government ensures there being low-cost operational costs to support low-cost air travel.

(Copyright 2012 Asia Times Online (Holdings) Ltd. All rights reserved. Please contact us about sales, syndication and republishing.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)