'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Kodungallur. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Kodungallur. Show all posts

Wednesday, 10 March 2021

Saturday, 14 December 2019

Ahoy, Muziris: Revisiting Kerala port’s illustrious past

Written by Vishnu Varma in The Indian Express

On a recent morning, I stood at the boat jetty at Kottapuram on the outskirts of Kodungallur town in central Kerala gazing at the dark green waters of the Periyar that flowed listlessly before me. A couple of air-conditioned water taxis, painted in bright colours, glistened in the sun as they stood docked to the jetty, ready to spring to life any second. In the far distance, a concrete bridge, on which cars, buses and trucks could be seen scurrying like ants, connected two islands.

The serene setting that day, however, betrayed a topography that was wildly different more than three centuries ago. At and around the spot where I stood, it’s believed that a vibrant urban port by the name of Muziris, or Muciri, used to exist, frequented by merchants who sailed from far-off lands such as Greece, Rome, Persia, Arabia and China in search for spices and semi-precious stones.

A view of the boat jetty at Chendamangalam near Paravur. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

A view of the boat jetty at Chendamangalam near Paravur. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

Historical accounts of those including Pliny and early Sangam literature have indicated that Muziris was a thriving trading centre — an important halt on the Spice Route and a gateway for those fleeing persecuted lands. It is said that the port remained one of the busiest on the Malabar coast for a long time until a cataclysmic event, perhaps a cyclone, in 1341 sunk the port bringing irreversible changes to the geography of the region, particularly the Periyar river. The kings and queens that ruled over Kerala in subsequent years have been unsuccessful in building ports and harbours that matched the elegance and grandeur of Muziris.

Now, centuries later, an ambitious tourism-conservation project under the aegis of the Kerala government is attempting to revisit Muziris’ illustrious past and the cultural and religious amity it was once home to. The Muziris Heritage Project is the brainchild of finance minister TM Thomas Isaac, who grew up in the region around Kodungallur (erstwhile Cranganore), and aims to safeguard the cultural assets of a bygone era of the region including temples, synagogues, churches, mosques, museums, palaces and fort ruins. In the last decade, several of such sites have been brought back to life and assembled as part of curated tours for visitors.

Accompanied by a guide, I set off on a journey that transcends across different periods of time and revisits important junctures in the history of Kerala. While there are different travel options for visitors vis-a-vis land and water, I took the latter, settling myself into a water-taxi.

The water-taxi started off by gently gliding through the waters, picking up speed in the middle as it cruised past Chinese fishing nets and men in wooden canoes. The journey offers visitors a beautiful sketch of the quintessential Kerala countryside centered around fishing. On one side, caged fish farming is being practiced with local varieties such as pearl spot, bluefin trevally and red snapper. Houses, on either banks, are painted in bright colours. A little ahead, fishing boats of varying sizes are docked. These are the ones that go to sea and their livery give a sense of which state they belong to.

“Blue is for the ones registered in Kerala, green for Tamil Nadu and red for Karnataka,” our boat captain informs us. The bigger boats go out to sea for two weeks at a time while the smaller ones come back after an overnight journey. There’s also a smattering of ice processing plants and boat-building and repairing units on both sides of the river: an entire industry built upon fishing. A little ahead, the boat captain slows down, pointing to the Chinese fishing nets which are now scattered across the expanse river. The channels around the nets are narrow and he has to be extremely careful to guide the boat through them without crashing against the nets. Soon we leave the main waterway to turn into a much smaller canal that brings us to our first stop: the Paravur jetty and the adjoining Paravur synagogue.

An ode to Kerala’s Jewish history

The tolerant and benevolent nature of the Chera kings of erstwhile Cranganore is reflected heavily in the multi-ethnic society consisting of Jews, Christians and Muslims alongside Hindus in those times. The early Jewish settlers, whose roots purportedly date back to the time of King Solomon, were rewarded with land by the Chera kings to establish synagogues and the one at Paravur is Kerala’s oldest one.

Inside the courtyard of the synagogue at Paravur, the oldest in Kerala. It fell into disrepair in the early 50s after the last of the Jews left Indian shores for Israel. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

Inside the courtyard of the synagogue at Paravur, the oldest in Kerala. It fell into disrepair in the early 50s after the last of the Jews left Indian shores for Israel. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

A two-minute walk from the Paravur jetty, the synagogue here is Kerala’s oldest and one of the few surviving structures. Built in 1615, the building is a fascinating confluence of Jewish traditions and Kerala style of architecture. The presence of a ‘padippura’ (gateway) and a large courtyard are testament to that. “A small door has been carved out of a bigger gate so that those entering would have to bow their heads down signifying respect to God and the place of worship,” our guide Vipin explains.

Its roof crafted out of teak wood and the structure resting on giant pillars, the Jewish temple is unique for its separate stairway for women that leads them directly to the upper gallery. The chandeliers and other decorative pieces have long been stolen, but extensive restorative works have been carried out inside. The temple had fallen into disrepair in the early 50s when the last of the Jews left the region for Israel as part of Aliyah.

A stone that was used to mark the border of the Kochi-Travancore kingdoms before independence in Kerala. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

A stone that was used to mark the border of the Kochi-Travancore kingdoms before independence in Kerala. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

Osnat Kalati, who had flown down from Israel to visit the synagogue that was once a place of worship for her parents, said it was a surreal feeling to come back to her roots. “My parents were born here and lived here until 1954. Three of my siblings were born here as well, but I was conceived in Israel,” she said.

The birthplace of Sahodaran Ayyappan

We get back to the boat to sail to our next stop, the birthplace of social reformer and thinker Sahodaran Ayyappan. This is an important halt in examining the state’s 19th century renaissance movements that brought in progressive social reforms and, in particular, paying obeisance to a man who ripped apart caste inequalities with his actions.

Ayyappan was born in August 1989 into an Ezhava (OBC) family of Ayurvedic physicians in Cherai near Kochi. Spurred by his association with eminent thinkers like Sree Narayana Guru and Kumaran Asan, Ayyappan was a vocal opponent of the caste system and laid the foundation for the ‘Sahodara Sangham’ (Brotherhood Association). In 1917, he proposed the idea of ‘misrabhojanam’ (a feast where people of all castes dine together), a revolutionary idea at that time, and conducted it at the home of his nephew. While the upper castes and even his own community of Ezhavas vociferously attacked him for dining with the ‘untouchables’, it earned him the moniker of Sahodaran Ayyappan (Brother Ayyappan) and fired of social equality into the minds of the masses.

The thatched hut where Kerala’s leading social reformer and anti-caste hero Sahodaran Ayyappan was born. A museum and library in his memory stands adjoining the hut. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

The thatched hut where Kerala’s leading social reformer and anti-caste hero Sahodaran Ayyappan was born. A museum and library in his memory stands adjoining the hut. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

A small thatched hut, renovated and rebuilt over time, where Ayyappan was born, stands as a testimony to his position in the pantheon of Kerala’s social reformers. The hut is a ‘moonu-kettu’ (three-faced) as Ezhavas in those times were not allowed to build houses bigger than that. A sculpture stands on one side of the hut, similar to The Last Supper, showing a bunch of people belonging to different castes taking part in the ‘misrabhojanam’. There’s also a digital library and facilities for a writers’ residency for those aspiring to study and research the life of Ayyappan.

Cranganore’s military prowess

By the time we leave Ayyappan’s museum, the sun is directly over us, forcing us to break for lunch. The boat glides towards Munambam, one of Kochi’s major harbours, and the mouth of the Arabian Sea where the waves are rough before taking a turn back toward the Kottappuram jetty where we started off. If one is lucky, dolphins can be seen leaping through the waters, our guide informs us.

One of the restaurants at the Kottapuram jetty where tourists can gorge on sumptuous Kerala cuisine. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

One of the restaurants at the Kottapuram jetty where tourists can gorge on sumptuous Kerala cuisine. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

The restaurants, particularly The Portuguese, beside the Kottappuram jetty, offer authentic local Kerala cuisine for tourists. After a sumptuous meal of roti with tawa-fried pearl spot fish and bird’s eye chilli chicken washed down with some pomegranate juice, we set off for the third stop of the tour — the remains of what was once a sturdy and magnificent military fortress.

The excavated remains of the once-military fortress of Kottapuram which was used by the Portuguese and the Dutch before it was transferred into the Travancore Royal Family. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

The excavated remains of the once-military fortress of Kottapuram which was used by the Portuguese and the Dutch before it was transferred into the Travancore Royal Family. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

The Kottappuram fort, standing at the mouth of the Periyar, was built by the Portuguese in 1523 before it was captured by the Dutch, dismantled and rebuilt in 1663. The fort, that offered breathtaking views of the river and the sea beyond, was a precious asset for colonial powers and regional kingdoms to monitor enemy ships.

“The fort once comprised of six small churches, a cathedral, military camps, granaries and workshops over a 10.5 acre land. According to records, the fort was purchased by the Travancore kings in 1789 from the Dutch at an estimated sum of Rs three lakhs. But later, during Tipu Sultan’s conquest, the fort, under the leadership of an English officer, was said to have been emptied and demolished completely to prevent the former’s advance,” said Lalji, a staff of the state archeological department which maintains the site.

Wide windows with glass shutters at the Paliam palace, a marker of Dutch architecture. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

Wide windows with glass shutters at the Paliam palace, a marker of Dutch architecture. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

Parts of the fort have been dug out in recent excavations of the archeological department, offering fascinating glimpses into the life of the people of the bygone era. Pearls, coins, plates, canon parts, iron and glass objects were also dug out. In a rare and significant finding in 2010, remains of a skeleton dating back to 1540-1550 were also uncovered and was subsequently stored in a box at the site. “It was found to be that of a man below the age of 20. His left hand was missing,” Lalji added.

The feudal chieftains of Paliam

The final destination of our journey ends at the imposing household-turned-museum of the Paliath family, who ruled as the hereditary prime ministers of the kingdom of Cochin between the 17th and 19th centuries and second only to the Maharaja. A five-minute walk from the jetty at Chendamangalam, located on a rivulet of the Periyar, the Paliam ‘nalukettu’ (four-faced household) and the Paliam Kovilakam have been transformed into museums under the heritage project and offer a snapshot of the once-grand lives of the members of the feudal family.

The centuries-old household of the Paliam family, the male members of which were designated as the prime ministers of the Cochin kingdom. Only female members of the family and children were allowed inside this house. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

The centuries-old household of the Paliam family, the male members of which were designated as the prime ministers of the Cochin kingdom. Only female members of the family and children were allowed inside this house. (Express Photo: Vishnu Varma)

Chendamangalam was said to be a wasteland before the Paliath family arrived from the Malabar. With their arrival, development began trickling in. The origins of the stone-work, gold-work and handloom industries in Chendamangalam today are all rooted to the family.

It has also played a pivotal role in the battles that the Cochin kingdom fought with colonial powers and with other local rival armies. During the conquest of Hyder Ali in 1776, the then chief of the family was able to eke out a treaty between him and the Cochin king that kept truce between the two powers.

The meteoric rise of the family, after being endowed with land grants and the title of prime-ministership by the king of Cochin, led to the popular adage ‘kochiyil pathi paliyam’ (Paliyam owns half of Kochi). While the male members of the family, including the head, resided in a two-storey official residence which was gifted by the Dutch, the female members stayed in a separate adjoining household. Both of these structures are fascinating architectural wonders, crafted out of the finest teak wood and replete with luxurious facilities.

“The household, restricted to women and children of the family, is about 234 years old. Each wing of the house has specific uses. For example, the east wing is primarily used for functions such as births, marriages and even deaths. In the west wing, we can see a locker which contained all the valuables. Underneath the locker, it’s said that a tunnel begins, leading up to Kottayil Kovilakom, a nearby household,” Rakhi, a guide, explains.

Today, the museums at Paliam reflect and celebrate local history, folklore and architecture of the region. Officials of the heritage project say there’s enough historical material in the Chendamangalam area alone to set up at least 29 museums dealing with religious, cultural and social aspects of the people and the feudal leaders that lived through the ages.

As the evening sun cast its glow on the village and the surrounding islets of the Periyar, I wrapped up my tour, with the sensation of having travelled through different time periods in a matter of hours. A journey through time indeed.

Thursday, 11 August 2016

Muziris or Kodungallur: Did black pepper cause the demise of India's ancient port?

In the first century BC it was one of India’s most important trading ports, whose exports – especially black pepper – kept even mighty Rome in debt. But have archaeologists really found the site of Muziris, and why did it drop off the map?

By Srinath Perur in The Guardian

Excavations in the village of Pattanam, Kerala, have raised questions about whether the site is ‘urban’ enough to be Muziris. Photograph: KCHR

“This was a centre of paramount importance for Roman trade,” says Federico De Romanis, associate professor of Roman history at the University of Rome Tor Vergata. “What made it absolutely unique was the considerable amounts of black pepper exported from Muziris. We are talking about thousands of tons.”

In addition to pepper, De Romanis says, exports included both local products – ivory, pearls, spices such as malabathron – and those from other parts of India, including semi-precious stones, silks and the aromatic root nard. “These attest to commercial relationships nurtured with the Gangetic valley and east Himalayan regions.”

In the other direction, ships arrived with gold, coral, fine glassware, amphorae of wine, olive oil and the fermented fish sauce called garum. But the value of this trade was lopsided: De Romanis says Pliny the Elder estimated Rome’s annual deficit caused by imbalanced trade with India at 50m sesterces (500,000 gold coins of a little less than eight grammes), with “Muziris representing the lion’s share of it”.

Maritime trade between Muziris and Rome started in the first century BC, when it became known that sailing through the Red Sea to the horn of Africa, then due east along the 12th latitude, led to the Kerala coast. “Muziris was entirely dependent on foreign, especially Roman, demand for pepper,” De Romanis says. So when the Roman empire’s economy began to struggle in the third century AD, he believes the trade in pepper reconfigured itself, and Muziris lost its importance.

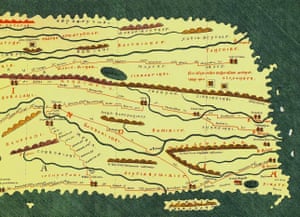

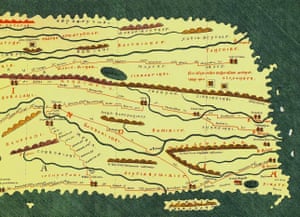

Muziris pictured (bottom right) in the Tabula Peutingeriana, a fifth-century map of the world as seen from Rome

Dr PJ Cherian, director of the Kerala Council for Historical Research, confirms there are few references to Muziris after the fifth century AD. It had been generally assumed that Muziris referred to the port of Kodungallur, which had been put out of commission by devastating floods in 1341 – but excavations there did not turn up anything older than the 13th century.

Travel 11 kilometres by road from Kodungallur, however, and you reach the village of Pattanam. For years, children there had been collecting beads that would rise to the surface during the monsoon season. After an initial dig in 2004,systematic excavations by Cherian and his colleagues began in 2007. Soon, he says, it was clear they had discovered a major archaeological site.

Over nine seasons of excavations, they have found Roman amphorae (for the first time on the Keralan coast), a wharf-like structure, a dug-out canoe that is approximately 2,000 years old – plus foundations, bricks and tiles, tools and artefacts made of iron, lead and copper, glass beads, gold ornaments and semi-precious stones clearly meant for export.

So, is Pattanam the site of fabled Muziris? There isn’t clinching evidence yet, but Cherian thinks it’s likely. He is also tired of questions about the Roman connection, asking: “When they excavate a Roman site in Europe, do they obsess similarly about whether it traded with India?” To him, an integral part of the excavation is what it reveals about the people who actually lived there.

Tathagata Neogi, of the Indian Institute of Archaeology, explains the stages of occupation in Pattanam using a large photograph of an excavated trench’s cross-section. Human habitation began there around 1000BC, marked by characteristic Iron Age black and redware pottery, while the period between 500 and 300BC marks a mixed phase.

“We think this is when Pattanam began making the transition from a village to a trade hub,” Neogi says. The period from 300BC to AD500 is densely packed with evidence for trade both within and outside India. Burnt bricks and tiles, terracotta ring wells and coins suggest a thriving settlement. Small amounts of west Asian pottery in the earlier portions of this segment provide evidence for pre-Roman maritime trade. After AD500 the record thins out – until AD1500, when Chinese and European ceramics are found.

Is Pattanam ‘urban’?

Today, Pattanam is a village situated four kilometres from the sea. The vegetation is typical of the region: tall arcing palms, squat plantains, vines and creepers, near-flourescent monsoon grass. There are sporadic houses, a temple, a village office and sudden channels of water.

The archaeological mound at Pattanam is around 70 hectares; atop it sits a museum displaying finds from the excavations. It is curious, Cherian notes, that a village should be named Pattanam, a word that means market-town or trading port across south India.

Some historians – such as Rajan Gurukkal, author of Rethinking Classical Indo-Roman Trade – have argued that Pattanam (which he believes is the location of Muziris) was likely nothing more elaborate than a colony of Mediterranean merchants, plus the inland traders and artisans who dealt with them. Gurukkal’s theory is based on the apparent absence of permanent structures, and the seeming disconnect of the materials and skills found at Pattanam with those of the wider region. He suggests the colony might even have been seasonal, inhabited only when ships arrived for trade.

Such a debate comes down to what is meant by a city or urban settlement. According to Cherian, “Urban is a complicated word – to me, it means ‘organised’, ‘thought out’, ‘planned’.” And he sees evidence of this in Pattanam: “It was certainly a city, but of its time.”

The excavations have revealed what appear to be toilets, drains and terracotta ring wells, and these – along with raised foundations aligned in one direction – suggest a planned settlement.

A channel of the Periyar river near Pattanam. Photograph: Srinath Perur

Cherian also thinks the level of technological accomplishment – the quality of mortar in a wharf structure; evidence of intricate glass and stone work – and the high density of potsherds (some 4.5 million have been recovered so far) all point to a settlement that was urban in character. The local coins suggest a monetised economy and a degree of political organisation.

“We now recognise that ancient cities could look very different from their modern counterparts, even as they had the same functions of trade and economic integration,” says Monica Smith, professor of anthropology at UCLA, who studies newly emergent urbanism in the Indian subcontinent.

“It used to be felt, by 20th-century archaeologists such as V Gordon Childe, that monumental architecture was required before a site could be defined as a ‘city’. In addition, there was often a sense that a city should have a high density of concentrated populations at their core, in which that density was focused on a particular religious or administrative purpose such as a palace or temple.”

But Smith offers an example for a more spread-out idea of a city: the large Kumbh Mela camps in India, which come up only for the duration of the congregation, are well-planned, possess infrastructure, and have an “urban atmosphere”. She adds: “We can envision that temporary or sequential occupations could have been the case in ancient cities as well.”

Smith suggests such sites can grow in extent very quickly, especially when demand for a new commodity is high (black pepper, in the case of Pattanam). “This is why research of the kind done at Pattanam is particularly important. It can help us understand the dynamic changes over time, and evaluate the extent to which investments in features such as wharves and ring wells signalled a ‘core’ location around which surrounding suburbs grew.”

A more complete understanding of the Pattanam site – and its flavour of urbanism – will take a while yet, however. According to Cherian: “Less than one percent of the site has been excavated. We have only touched the tip of the iceberg.”

The quest for Muziris may or may not be over. But as De Romanis says: “Pattanam is the closest thing to Muziris we have got so far. Whatever it was, it should be treasured and taken care of.”

By Srinath Perur in The Guardian

A painting of Muziris by the artist Ajit Kumar. In 2004, excavations in Kerala sparked new interest in this lost port. Illustration: KCHR

Around 2,000 years ago, Muziris was one of India’s most important trading ports. According to the Akananuru, a collection of Tamil poetry from the period, it was “the city where the beautiful vessels, the masterpieces of the Yavanas [Westerners], stir white foam on the Periyar, river of Kerala, arriving with gold and departing with pepper.”

Another poem speaks of Muziris (also known as Muciripattanam or Muciri) as “the city where liquor abounds”, which “bestows wealth to its visitors indiscriminately” with “gold deliveries, carried by the ocean-going ships and brought to the river bank by local boats”.

The Roman author Pliny, in his Natural History, called Muziris “the first emporium of India”. The city appears prominently on the Tabula Peutingeriana, a fifth-century map of the world as seen from Rome. But from thereon, the story of this great Indian port becomes hazy. As reports of its location grow more sporadic, it literally drops off the map.

In modern-day India, Muziris was much more of a legend than a real city – until archaeological excavations in the southern state of Kerala, starting in 2004,sparked reports of a mysterious lost port. Though the archaeologists cannot be certain, they – and, with some exceptions, historians too – now believe they have located the site of Muziris.

Around 2,000 years ago, Muziris was one of India’s most important trading ports. According to the Akananuru, a collection of Tamil poetry from the period, it was “the city where the beautiful vessels, the masterpieces of the Yavanas [Westerners], stir white foam on the Periyar, river of Kerala, arriving with gold and departing with pepper.”

Another poem speaks of Muziris (also known as Muciripattanam or Muciri) as “the city where liquor abounds”, which “bestows wealth to its visitors indiscriminately” with “gold deliveries, carried by the ocean-going ships and brought to the river bank by local boats”.

The Roman author Pliny, in his Natural History, called Muziris “the first emporium of India”. The city appears prominently on the Tabula Peutingeriana, a fifth-century map of the world as seen from Rome. But from thereon, the story of this great Indian port becomes hazy. As reports of its location grow more sporadic, it literally drops off the map.

In modern-day India, Muziris was much more of a legend than a real city – until archaeological excavations in the southern state of Kerala, starting in 2004,sparked reports of a mysterious lost port. Though the archaeologists cannot be certain, they – and, with some exceptions, historians too – now believe they have located the site of Muziris.

Excavations in the village of Pattanam, Kerala, have raised questions about whether the site is ‘urban’ enough to be Muziris. Photograph: KCHR

“This was a centre of paramount importance for Roman trade,” says Federico De Romanis, associate professor of Roman history at the University of Rome Tor Vergata. “What made it absolutely unique was the considerable amounts of black pepper exported from Muziris. We are talking about thousands of tons.”

In addition to pepper, De Romanis says, exports included both local products – ivory, pearls, spices such as malabathron – and those from other parts of India, including semi-precious stones, silks and the aromatic root nard. “These attest to commercial relationships nurtured with the Gangetic valley and east Himalayan regions.”

In the other direction, ships arrived with gold, coral, fine glassware, amphorae of wine, olive oil and the fermented fish sauce called garum. But the value of this trade was lopsided: De Romanis says Pliny the Elder estimated Rome’s annual deficit caused by imbalanced trade with India at 50m sesterces (500,000 gold coins of a little less than eight grammes), with “Muziris representing the lion’s share of it”.

Maritime trade between Muziris and Rome started in the first century BC, when it became known that sailing through the Red Sea to the horn of Africa, then due east along the 12th latitude, led to the Kerala coast. “Muziris was entirely dependent on foreign, especially Roman, demand for pepper,” De Romanis says. So when the Roman empire’s economy began to struggle in the third century AD, he believes the trade in pepper reconfigured itself, and Muziris lost its importance.

Muziris pictured (bottom right) in the Tabula Peutingeriana, a fifth-century map of the world as seen from Rome

Dr PJ Cherian, director of the Kerala Council for Historical Research, confirms there are few references to Muziris after the fifth century AD. It had been generally assumed that Muziris referred to the port of Kodungallur, which had been put out of commission by devastating floods in 1341 – but excavations there did not turn up anything older than the 13th century.

Travel 11 kilometres by road from Kodungallur, however, and you reach the village of Pattanam. For years, children there had been collecting beads that would rise to the surface during the monsoon season. After an initial dig in 2004,systematic excavations by Cherian and his colleagues began in 2007. Soon, he says, it was clear they had discovered a major archaeological site.

Over nine seasons of excavations, they have found Roman amphorae (for the first time on the Keralan coast), a wharf-like structure, a dug-out canoe that is approximately 2,000 years old – plus foundations, bricks and tiles, tools and artefacts made of iron, lead and copper, glass beads, gold ornaments and semi-precious stones clearly meant for export.

So, is Pattanam the site of fabled Muziris? There isn’t clinching evidence yet, but Cherian thinks it’s likely. He is also tired of questions about the Roman connection, asking: “When they excavate a Roman site in Europe, do they obsess similarly about whether it traded with India?” To him, an integral part of the excavation is what it reveals about the people who actually lived there.

Tathagata Neogi, of the Indian Institute of Archaeology, explains the stages of occupation in Pattanam using a large photograph of an excavated trench’s cross-section. Human habitation began there around 1000BC, marked by characteristic Iron Age black and redware pottery, while the period between 500 and 300BC marks a mixed phase.

“We think this is when Pattanam began making the transition from a village to a trade hub,” Neogi says. The period from 300BC to AD500 is densely packed with evidence for trade both within and outside India. Burnt bricks and tiles, terracotta ring wells and coins suggest a thriving settlement. Small amounts of west Asian pottery in the earlier portions of this segment provide evidence for pre-Roman maritime trade. After AD500 the record thins out – until AD1500, when Chinese and European ceramics are found.

Is Pattanam ‘urban’?

Today, Pattanam is a village situated four kilometres from the sea. The vegetation is typical of the region: tall arcing palms, squat plantains, vines and creepers, near-flourescent monsoon grass. There are sporadic houses, a temple, a village office and sudden channels of water.

The archaeological mound at Pattanam is around 70 hectares; atop it sits a museum displaying finds from the excavations. It is curious, Cherian notes, that a village should be named Pattanam, a word that means market-town or trading port across south India.

Some historians – such as Rajan Gurukkal, author of Rethinking Classical Indo-Roman Trade – have argued that Pattanam (which he believes is the location of Muziris) was likely nothing more elaborate than a colony of Mediterranean merchants, plus the inland traders and artisans who dealt with them. Gurukkal’s theory is based on the apparent absence of permanent structures, and the seeming disconnect of the materials and skills found at Pattanam with those of the wider region. He suggests the colony might even have been seasonal, inhabited only when ships arrived for trade.

Such a debate comes down to what is meant by a city or urban settlement. According to Cherian, “Urban is a complicated word – to me, it means ‘organised’, ‘thought out’, ‘planned’.” And he sees evidence of this in Pattanam: “It was certainly a city, but of its time.”

The excavations have revealed what appear to be toilets, drains and terracotta ring wells, and these – along with raised foundations aligned in one direction – suggest a planned settlement.

A channel of the Periyar river near Pattanam. Photograph: Srinath Perur

Cherian also thinks the level of technological accomplishment – the quality of mortar in a wharf structure; evidence of intricate glass and stone work – and the high density of potsherds (some 4.5 million have been recovered so far) all point to a settlement that was urban in character. The local coins suggest a monetised economy and a degree of political organisation.

“We now recognise that ancient cities could look very different from their modern counterparts, even as they had the same functions of trade and economic integration,” says Monica Smith, professor of anthropology at UCLA, who studies newly emergent urbanism in the Indian subcontinent.

“It used to be felt, by 20th-century archaeologists such as V Gordon Childe, that monumental architecture was required before a site could be defined as a ‘city’. In addition, there was often a sense that a city should have a high density of concentrated populations at their core, in which that density was focused on a particular religious or administrative purpose such as a palace or temple.”

But Smith offers an example for a more spread-out idea of a city: the large Kumbh Mela camps in India, which come up only for the duration of the congregation, are well-planned, possess infrastructure, and have an “urban atmosphere”. She adds: “We can envision that temporary or sequential occupations could have been the case in ancient cities as well.”

Smith suggests such sites can grow in extent very quickly, especially when demand for a new commodity is high (black pepper, in the case of Pattanam). “This is why research of the kind done at Pattanam is particularly important. It can help us understand the dynamic changes over time, and evaluate the extent to which investments in features such as wharves and ring wells signalled a ‘core’ location around which surrounding suburbs grew.”

A more complete understanding of the Pattanam site – and its flavour of urbanism – will take a while yet, however. According to Cherian: “Less than one percent of the site has been excavated. We have only touched the tip of the iceberg.”

The quest for Muziris may or may not be over. But as De Romanis says: “Pattanam is the closest thing to Muziris we have got so far. Whatever it was, it should be treasured and taken care of.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)