'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Monday, 31 May 2021

Saturday, 29 May 2021

Thursday, 27 May 2021

Monday, 24 May 2021

Modi II: Kerala’s Communist CM borrows from PM Modi’s playbook in his second innings

Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan at a press conference after the Left Democratic Front won the assembly election, at Kannoor in Dharmadom Sunday | Photo: ANI

Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan at a press conference after the Left Democratic Front won the assembly election, at Kannoor in Dharmadom Sunday | Photo: ANIOf all the wannabe Modis in Indian politics, this one must make the Prime Minister’s 56-inch chest swell with pride and satisfaction — a dyed-in-the-wool comrade from Kerala, Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan.

Though often dubbed as “dhoti-clad Modi” for what his critics believed was his autocratic style of functioning and intolerance to dissent, Vijayan has started copying Narendra Modi’s governance model in earnest only in his second innings as CM.

His first act after winning another term in Kerala last week — picking up his ministers and allocation of portfolios — had Modi’s imprint all over. The CM has entrusted himself with the charge of “all important policy matters”, apart from 27 departments.

This means that no minister in the Kerala government would be able to take any policy decision without the approval of the CM. All ministers in Kerala will effectively be puppets, with Vijayan pulling the strings. It’s straight out of PM Modi’s playbook.

The ‘Modi model’

After assuming office in 2014, Modi had done the same thing, taking charge of “all important policy issues”, apart from other portfolios. It dawned on his ministers soon that they were mere puppets with a symbolic role in policymaking, if at all.

In another move, the Vijayan-controlled Communist Party of India (Marxist) secretariat has decided that private secretaries of the ministers would be nominated by the party. It was similar to what had happened after the Modi government took over in 2014. It issued guidelines that any officer, official or private person, who had worked as personal staff (PS) of a minister in the previous United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government wouldn’t be appointed for the same role in the NDA government. The reason cited was: “Due to administrative requirements.”

It was so strict that even Rajnath Singh, then home minister, couldn’t have a PS of his own choice — an IPS officer from the Uttar Pradesh cadre who had served as PS to a UPA minister — despite personally taking it up with the PMO. As it is, while bureaucrats who have to serve as PS of Modi’s ministers are closely vetted, most others, including officers on special duty (OSDs), are drawn from Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) or affiliated organisations, especially its students’ wing — the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP).

Pinarayi Vijayan has now got the CPI(M) to adopt this model in his government. The idea is simple: to watch over the ministers through their personal staff. In fact, a couple of years after this model had come into place in New Delhi, Vijayan seemed to have gotten drawn to the idea of having control over the personal staff of ministers. In December 2016, he had convened a meeting of these staff, which caused much heartburn among ministers.

Five years later, the CM has got the party to take away the ministers’ discretion in choosing their private secretaries.

Emulating Modi

It may be too early to say how far the Vijayan government would go in emulating the Modi model of governance in his second innings. Many in political circles are already drawing a parallel between the two, given how the Kerala CM dealt with his rivals and potential challengers in the party.

After taking over as Kerala CM in 2016, Vijayan had virtually shunted his arch-rival and former CM V.S. Achuthanandan into a sort of margdarshak mandal, making him chairman of the administrative reforms commission and keeping him out of poll campaigns. With pre-poll surveys predicting a historic second consecutive term for the Left, Vijayan went about getting rid of potential challengers, denying party tickets to those who had had two consecutive terms as legislators; it resulted in five ministers’ removal from the poll race. After the elections, he got rid of the rest of his potential challengers, dropping all ministers from the previous government in the name of inducting ‘fresh blood’.

Many comrades in Kerala may not be surprised by the turn of events in the first week of Vijayan’s second innings. The most powerful Communist leader in India today, Vijayan was dubbed as “dhoti-clad Modi” by his detractors to denote his authoritarian style of functioning and the use of the government and the party apparatus to promote his personality cult.

He was also accused of turning Kerala into a sort of police state. There were allegations of fake encounter killings of Maoists, custodial deaths and torture, and apathy to political violence and murders. Months ahead of the 2021 assembly election, he brought a controversial amendment to the Kerala Police Act, which was seen as an attempt to curb free speech in the garb of preventing social media abuse. The government later withdrew the amendment following much criticism.

In an interview to ThePrint in the run-up to the assembly polls, this is how Vijayan responded to his description as Kerala’s Modi: “I do not know what kind of person Narendra Modi is. The people of Kerala know what kind of person I am for many years. I don’t now have to emulate Narendra Modi. I have my own style and methods. Modi might have his own style.”

Seven weeks after that interview, Vijayan seems to have found merits in that description as he starts his second term, emulating Modi.

Sunday, 23 May 2021

Hard Choices in Palestine

In the anthology Negotiating in Times of Conflict, Anat Kurz describes the Israel-Palestine dispute as ‘a three-way conflict.’

There is, of course, the more well-known two-way tussle between the Israeli state and the government body in West Bank and Gaza. These Palestinian-majority regions came under the control of a partially self-governing body in 1994, after an agreement was signed in Oslo between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO), the largest Palestinian political entity. The reason Kurz explains the tussle as a three-way conflict is because of the presence of another influential Palestinian party, Hamas.

Hamas, which has had a problematic relationship with the PLO, appeared in 1987 as an ‘Islamist’ variant of the Palestinian nationalist movement. The PLO, ever since its inception in 1964, is of course an umbrella organisation comprising various secular Palestinian nationalist outfits. The PLO’s largest component party was always Fatah, headed by the late Yasser Arafat. Initially, the PLO was highly militant in its outlook and was involved in armed attacks against Israel. Many of its component factions were supported by the former Soviet Union and radical Arab nationalist regimes in Egypt, Iraq, Syria and Libya.

However, from the mid-1970s onwards, when most Arab countries began a process of repairing ties with Saudi Arabia and the US, Fatah decided to work towards building itself as a ‘legitimate’ face of Palestinian nationalism, recognised by the UN. In 1987, a spontaneous uprising erupted against Israel’s occupation armies in various Palestinian-majority regions. The uprising, called the intifada (rebellion), caught the PLO by surprise.

The uprising did not have a core group navigating it. It was mostly driven by young stone-throwing Palestinians, confronting heavily armed Israeli occupiers. Yet, the intifada had enough nuisance value to get the Israelis to talk with their main nemesis, Fatah, in Oslo. A deal was signed that handed over West Bank and Gaza to a partially autonomous government of Palestinians. During the 1996 elections here, the electorate handed the PLO a landslide victory and the mandate to rule West Bank and Gaza.

Hamas was the Palestinian wing of the Muslim Brotherhood — a pan-Islamist movement headquartered in Egypt — but one with a history of deriving clandestine support from Israel when the Brotherhood was being repressed by the Arab nationalist regimes in Egypt in the 1960s, and in Syria in the early 1980s.

According to Andrew Higgins, in the January 24, 2009 issue of the Wall Street Journal, Israel propped up Hamas to use it as a ‘counterweight’ against the PLO. The roots of this manoeuvre can be found in the late 1970s, when the Israeli state began to patronise an Islamist outfit called the Mujama al-Islamiya, which described itself as a charity organisation.

According to Higgins, the Egyptians had sidelined and banned the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist outfits in the Palestinian regions that were under Egyptian control till the 1967 Arab-Israel War. But once these regions fell in the hands of Israeli forces, the Israelis allowed the Islamist groups to operate, as long as they were anti-PLO.

With Israeli support, the Mujama and other such groups began to undermine the PLO’s influence. They organised charity programmes, establishing small clinics, schools and mosques and, in return, were able to recruit a large number of disillusioned Palestinians. Hamas treaded the same path until 1994, when the PLO agreed to recognise Israel as a country and, in exchange of which, Israel handed over the West Bank and Gaza to the Palestinians.

However, thus began campaigns of suicide bombings, assassinations and rocket attacks against Israel by Hamas, drawing vicious Israeli reprisals. The PLO had swept the 1996 elections, but Hamas won the 2006 elections. It received 44.45 percent of the total votes to the PLO’s 41.43 percent.

Fatah’s Muhammad Abbas had replaced Yasser Arafat as president of Palestine after Arafat’s demise in 2004. Tensions between the Fatah-led PLO and Hamas had been simmering since the 1990s. The PLO had agreed to end its policy of armed resistance and, as a result, the PLO’s presence and government were recognised by the international community. The PLO now favoured a settlement through negotiations and by providing jobs, education and security to the Palestinians.

The activities of Hamas in this context are focused more on the most impoverished areas of Palestine, especially in Gaza. Here, Hamas provides charity services and gains new recruits. It also amasses weapons that include rockets made in secret workshops by the locals. Hamas does not recognise Israel as a legitimate state. Its militant actions are often criticised by President Abbas who accuses Hamas of dragging Palestinians into a war that can be settled through negotiations.

In June 2007, fighting broke out between PLO and Hamas militants in Gaza. The fighting was intense. Over 600 people lost their lives. The conflict saw the ouster of the PLO from Gaza. This means there are now two governments in control of the Palestine territories. Fatah/PLO governs the West Bank region whereas Hamas is in control of Gaza.

Things became even more complex with the 2009 election of the populist Benjamin Netanyahu as Israel’s Prime Minister. Netanyahu toed a hard line and refused to stop Jewish people from settling in occupied Palestinian territory. Such settlements are against international mandates and opinion.

Interestingly, Netanyahu’s popularity in Israel has been decreasing. His conservative Likud Party has had to form shaky coalition governments. There have been four indecisive elections in Israel between 2019 and 2021. Netanyahu has also faced two criminal investigations against him.

The Israeli military’s recent attacks in Gaza that have killed hundreds of Palestinians were in retaliation to rockets fired towards Israel by Hamas from Gaza. But the tipping point was Netanyahu’s refusal to stop Israeli settlers from taking over Palestinian properties, and a brazen raid by Israeli soldiers against Palestinians worshipping inside the historic Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem.

It is likely that Netanyahu believes his hardline approach will reconfigure his dwindling electoral fortunes in Israel as he presents himself as a saviour of the Jewish homeland. To Hamas, Israeli violence and the outfit’s rocket attacks against Israel ‘prove’ that Palestine can only be liberated through an armed struggle.

Once again, crushed between the two is a more rational space that Fatah wants to explore. This is also the space that former US President Barack Obama favoured. But the current US president, Joe Biden, is busy sorting out differences of opinion on the dispute within his own multicultural government.

Some of his cabinet members are asking him to take the Obama route. But unlike Obama, till the writing of this piece, the Biden administration seems reluctant.

Thursday, 20 May 2021

How Sadhguru built his Isha empire. Illegally

Anish Daolagupu

Jaggi Vasudev, Anglophone India’s star godman, has challenged on more occasions than one that if the accusations of illegal deeds that have followed him around like ardent devotees were ever proved, he would quit India. The charges are legion, contained in testimonies of the allegedly wronged and tomes of government records. And there is much there, as Newslaundry found after examining a whole lot of them, to, at the very least, merit an investigation. Absent that, the accusations remain just that, accusations, merely a nuisance in his way as Vasudev goes about expanding his vast religio-cultural and business empire, the Isha Foundation. And, in the process, building himself up as arguably the country’s most influential godman.

But what precisely are the accusations against Vasudev, or Sadhguru as his devotees know him? Have they ever been investigated? If yes, what was the outcome? If no, why not? Did he use his godman persona and influence to indulge in illegalities or did the alleged illegalities enable his rise to fame and fortune?

To answer such questions, Newslaundry spoke with public servants, activists, and whistleblowers; trawled government records on the foundation; and examined court cases filed against them over the years and investigations conducted.

What we pieced together is really just the same old story of greed, corruption, and abuse of socio-religio-cultural sentiment for material enrichment. At the centre of this story is an Adivasi hamlet called Ikkarai Boluvampatti in Tamil Nadu’s Coimbatore.

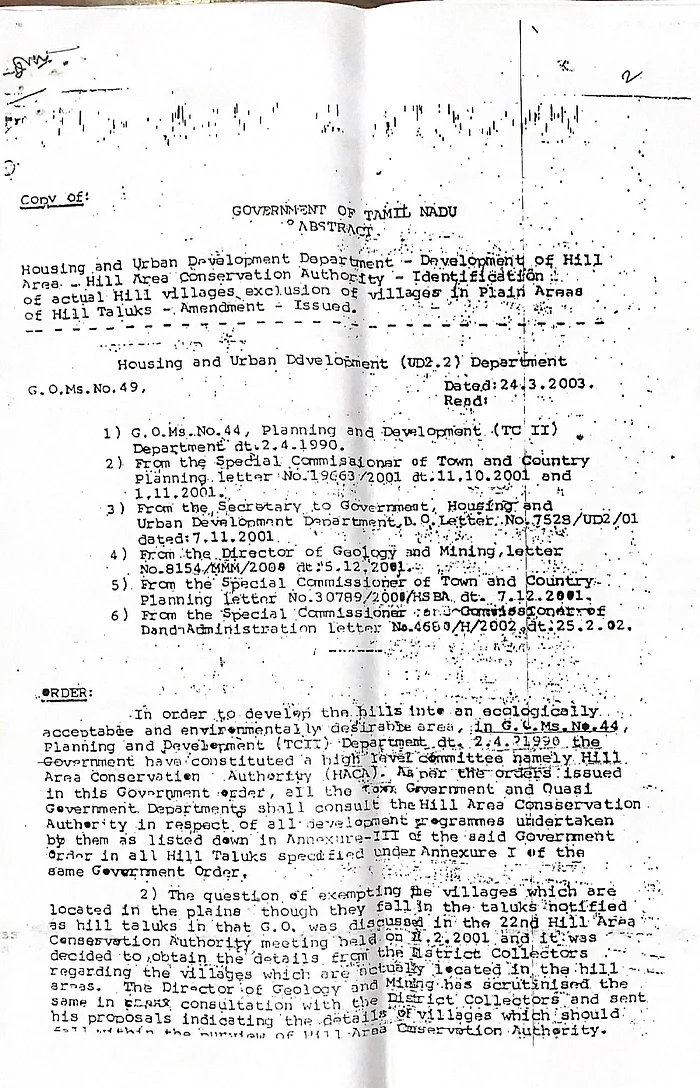

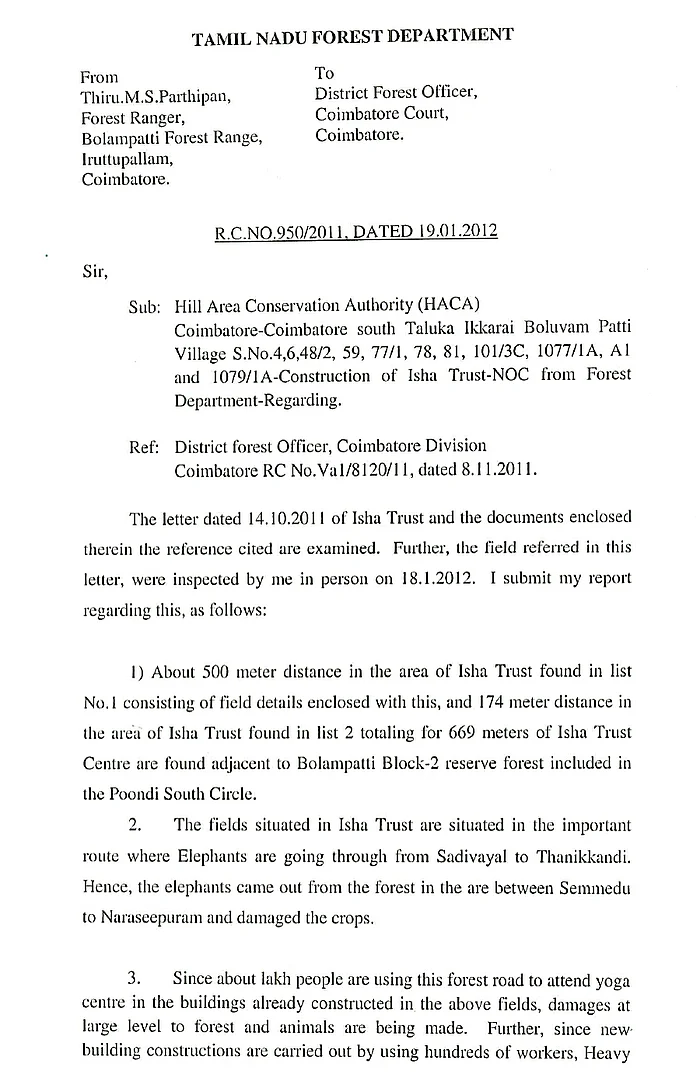

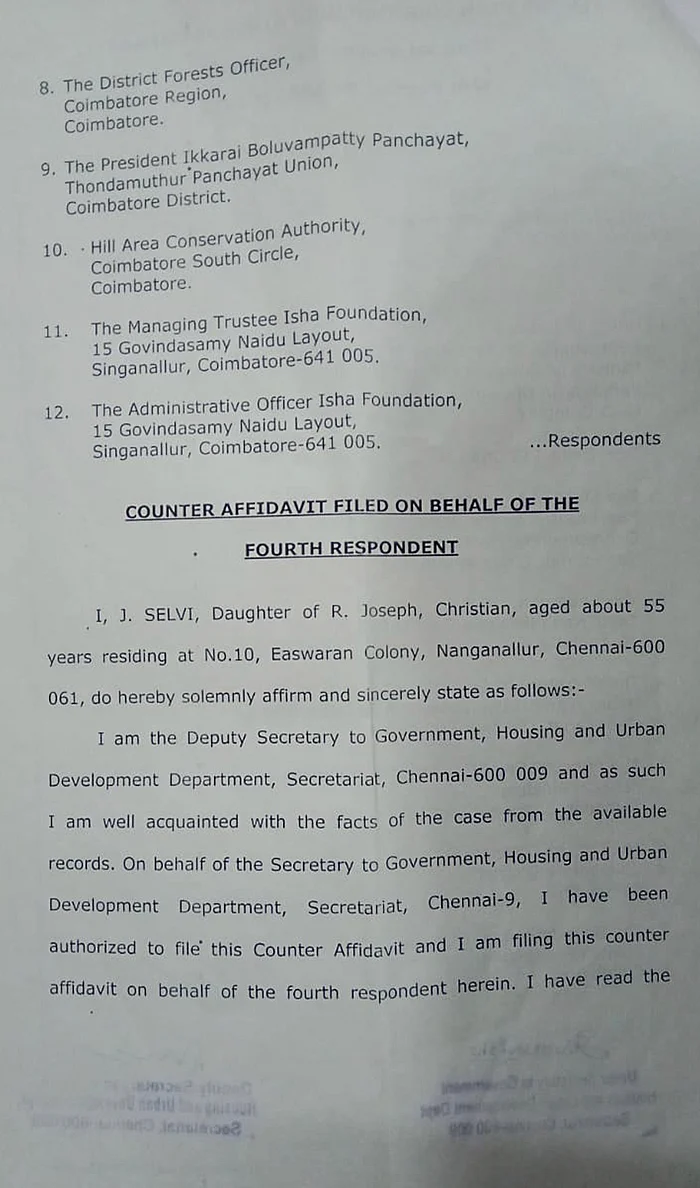

Ikkarai Boluvampatti, in the foothills of the Velliangiri hills, is where the Isha Foundation is headquartered on a sprawling 150-acre campus of 77 large and small structures, including the Isha ashram, built between 1994 and 2011 in blatant violation of laws and rules. The campus is adjacent to the Bolampatty Reserve Forest, an elephant habitat in the Nilgiris biosphere reserve, and along the Thanikandi-Marudhamalai migration corridor of the pachyderms. So, human activity, let alone construction, is regulated by the Hill Area Conservation Authority, or HACA, set up in 1990 to preserve wildlife and ecology of forested hill regions of Tamil Nadu.

Here, construction on over 300 sq metres of land can’t be done without HACA’s approval. Yet, records obtained by Newslaundry from the state departments of forest, town and country planning, and housing and urban development show that from 1994 to 2011, Isha constructed on 63,380 sq meters and created an artificial lake on another 1,406.62 sq metres at Ikkarai Boluvampatti, without approval. Vasudev and his foundation have said they got permission to build on about 32,855 sq metres from the local panchayat, but the rural body doesn’t have the power to authorise construction in areas under HACA.

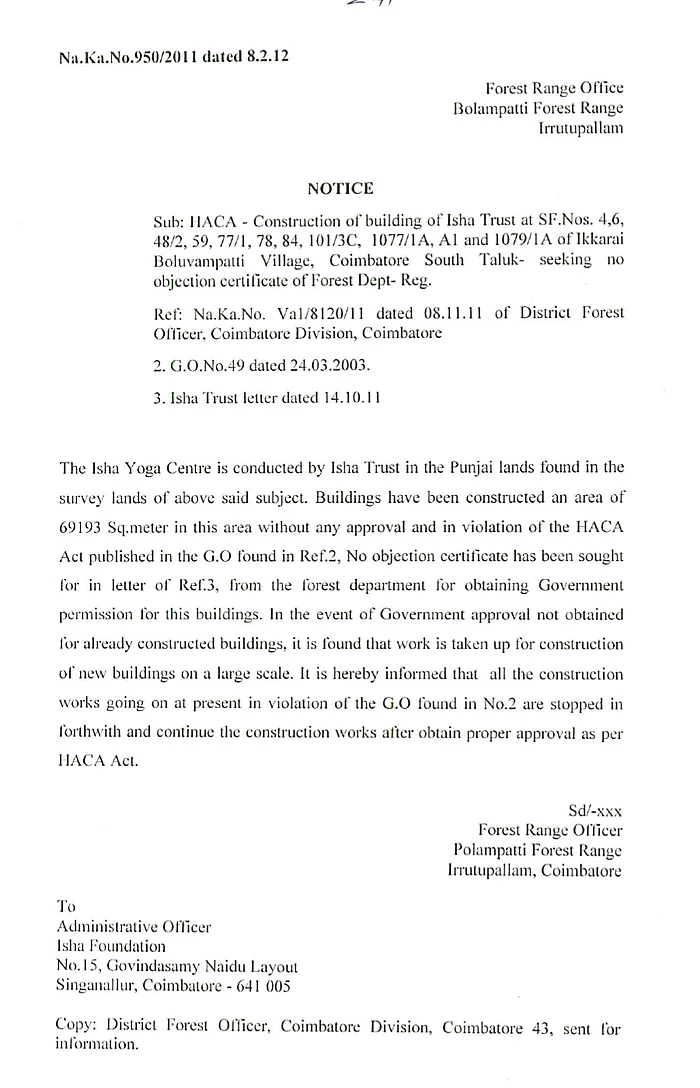

Isha did apply for approval from HACA in 2011, but after they had already built several structures. In July 2011, a forest department document shows, Isha asked HACA to greenlight illegal constructions on 63,380 sq meters as well as new constructions on 28582.52 sq metres. Taking up the application, V Thirunavukkarasu, then Coimbatore’s forest officer, visited the Isha ashram in February 2012. He found Isha had illegally constructed a series of buildings, including on the 28,582.52 sq meter plot for which it had gone to HACA for approval.

Thirunavukkarasu also found that the compound wall of the ashram and front gate were built from the forest land. Moreover, Isha’s many constructions and the resultant rush of visitors to the ashram had obstructed the elephant corridor, heightening man-animal conflict. So, he denied them approval. In October that year, Isha withdrew its application on the prexet of amending it. They didn’t file it again until 2014.

Thirunavukkarasu would return to Coimbatore as the chief conservator of forests in 2018, only to be moved out after just four days.

MS Parthipan, a forest ranger, too visited the Isha ashram in 2012. He found some of its lands fell on routes elephants used to move between Sadivayal and Thanikkandi. Since Isha had illegally erected buildings, walls and electric fences on these lands, elephants were forced to emerge from the forest between Semmedu and Narseepuram, trampling crops and attacking villagers.

“Any construction requiring over 300 sq meters of land requires HACA’s permission. Isha undertook construction without permission over a large area. They built structures first and then applied for approval. Whenever they did seek permission for new construction, they didn’t wait for our nod and simply started building,” a forest official who was privy to Parthipan’s inspection said on the condition of anonymity. “Isha’s lands were inside the elephant corridor and they were obstructing it, so they didn’t get clearance.”

Isha has marked at least 33 structures at the Ikkarai Boluvampatti campus for religious use which means they are considered public buildings under Tamil Nadu’s planning rules. Such structures require approvals from the district collector and the deputy director for town and country planning to build. Isha, records from the housing and urban development department show, didn’t bother taking these approvals.

Instead, they went to the panchayat, which isn’t empowered to grant such permissions without consulting the town and country planning department. The foundation did eventually go to the planning department for approval in 2011, but only after they had erected a series of structures – illegally. Aside from seeking approval for what they had built over the previous 15 years, the foundation asked the planning department for permission to construct 27 new buildings. The application, however, was incomplete and the department told them to file a new one by February 2012.

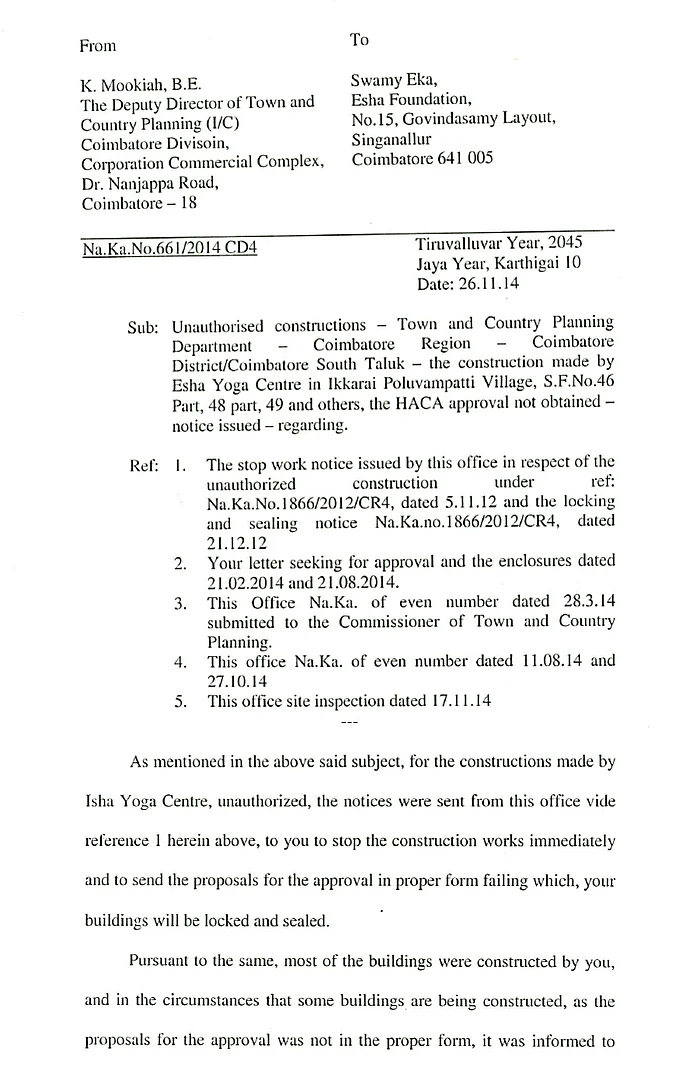

Isha breached the deadline and only sent a new application seven months later. Subsequently, when planning officials visited the ashram in October 2012 they found construction of the new buildings had already begun. They ordered the foundation to immediately stop all construction and followed up with a notice in November 2012. Isha didn’t care.

Finally, in December 2012, the planning department sent another notice directing Isha to demolish all illegal structures within a month. The foundation challenged the notice before the town and country planning commissioner. The matter is still hanging fire.

At the time, K Mookiah was deputy director, the town and country planning department, Coimbatore. Why did his department not act against Isha when they disregarded its orders? “After a month of issuing the notice I was transferred out,” he replied. “I don’t know what happened after that. I don’t know whether they have taken the approval or not.”

By 2012, Isha had constructed as many as 50 structures and was building 27 more, all illegally.

The foundation’s illegalities didn’t go unchallenged.

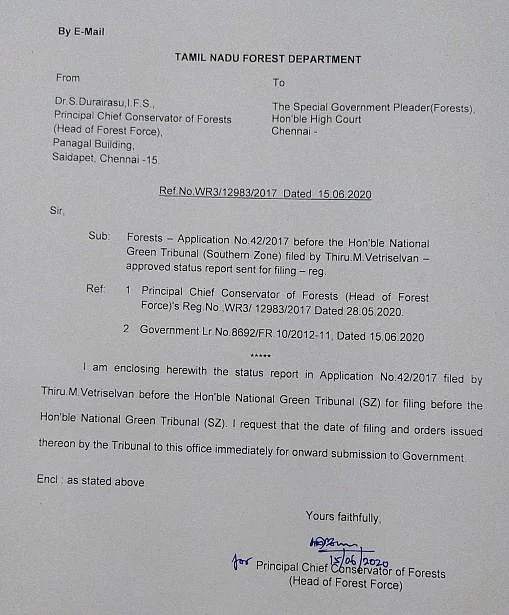

For the past eight years, M Vetri Selvan of the NGO Poovulagin Nanbargal has been fighting against Vasudev’s illegal constructions in the Madras high court, where he filed four petitions in 2013 and 2014. In his pleas, Selvan asked that the planning department’s order for demolition of Isha’s illegal structures be carried out, officials who had not acted against its illegalities be punished, Isha Sanskriti School’s illegal operation be stopped, and provision of cheap electricity to the Isha campus be stopped.

The pleas saw a total of 10 hearings from March 2013 to April 2014. And none since. “Our first petition regarding the demolition of Isha’s illegal construction was heard on March 8, 2013. A notice was issued to Isha, district collector, forest department, HACA, village panchayat. At the next hearing on March 25, 2013, Isha’s advocate sought time to file a counter.

On June 20, Isha, the planning department and the state government all filed their responses and the matter was adjourned. On August 22, 2013, we filed three more petitions and a combined hearing on all four pleas took place the next day. Both sides made arguments, but there was no reply from the state government and the matter was adjourned again,” he said. “At a hearing on March 13, 2014, the state school authority submitted that they hadn’t given Isha permission to run a school. After that, the court said the final hearing would happen once all the respondents had filed their counters. There has been no hearing since.”

In 2017, Selvan filed a petition against Isha’s Mahashivratri celebration, but the court didn’t entertain it because his previous pleas were still pending.

“The court also said I’d filed the petition with ulterior motive,” he added. “Man-animal conflict in and around the forests of Coimbatore has seen a spurt in the past 15-20 years. Primary reason is illegal construction in the elephant habitat, and Isha is involved on a wide scale. We are trying to save the natural environment of this area, to preserve its biodiversity. That’s why we are fighting against Isha’s illegal constructions. It’s not a personal feud.”

Isha's Adiyogi statue.

After he was turned away by the high court, Selvan went to the National Green Tribunal against Isha’s “destruction of environment and wildlife”. Three years later, the NGT directed Isha and the local administration to ensure big functions at the ashram such as the Mahashivratri celebration didn’t cause pollution.

Selvan wasn’t alone knocking the high court’s doors with a complaint against Isha in 2017. The Velliangiri Hill Tribal Protection Society also filed a plea, through P Muthammal, 49, an Adivasi from the Muttathu Ayal settlement in Ikkarai Boluvampatti.

Muthammal pleaded that rising man-animal conflict, for which Isha’s illegal constructions were mainly to blame, had made the lives of Adivasis difficult. He also objected to the foundation’s 112-foot Adiyogi statue, noting that it had been built without necessary clearances.

Replying to the petition, R Selvaraj, then deputy director, town and country planning, confirmed that the statue had been built without his department’s approval.

But by the time Selvaraj filed the reply, on February 28, 2017, the statue had already been inaugurated by none less than the prime minister.

That Modi didn’t hesitate to inaugurate the statue even though it was mired in a legal challenge was telling. A key reason Isha has got away with blatantly violating rules is that it has been enabled by political authorities, particularly the Tamil Nadu government.

Most blatantly, the forest department has dramatically changed its view that the Isha ashram is situated in the elephant corridor.

In 2012, records seen by Newslaundry show, Coimbatore’s forest officer told the state’s principal chief conservator of forests that Isha had built on land in the elephant corridor and its constructions and the rush of the devotees to the ashram – nearly two lakh on on Mahashivratri alone – had heightened man-animal conflict. Installation of powerful lights and high-decibel audio, not least for the Mahashivratri celebration, had only worsened the situation.

Similarly, a 2013 notification issued by the district collector stated in no uncertain terms, though without naming Isha, that illegal construction near the reserve forest in Ikkarai Boluvampatti was increasingly obstructing the corridor for elephants, causing the animals to damage life and property. The notice threatened to cut power, water ,sealing and demolition of the premises which had been built without HACA’s approval.

By 2020, however, the forest authorities were singing a discordant tune. In a June 2020 status report submitted to the National Green Tribunal, principal chief conservator of forests P Durairasu, claimed that the Isha campus was “adjacent” to the Ikkarai Boluvampatti Block 2 reserve forest, which was a “famous elephant habitat” but not a designated elephant corridor. For their yearly migration, he added, elephants passed near where the Isha ashram was situated in Ikkarai Boluvampatti but this spot wasn’t an authorised elephant corridor.

The swing in the forest department’s position on Ikkarai Boluvampatti would prove conveniently beneficial for Isha. In March last year, the EK Palaniswami government directed the regularisation of plots which have been built on without approval in the hill areas, including HACA lands that supposedly do not fall within the elephant corridor. They include Ikkarai Boluvampatti.

“We believe this rule has been brought to indirectly help the Isha Foundation regularise its illegal constructions,” claimed G Sundarrajan, an activist with the environmental advocacy group Poovulagin Nanbargal. “The government hasn’t yet notified they have made this rule.”

In 2017, after Isha had applied for HACA approval for constructions that they had already erected, H Basavraju, then the principal chief conservator, set up a committee to examine the submission. The committee found that Isha’s constructions were damaging to local wildlife and environment, and asked the district forest officer to recommend post-construction approval only if Isha made changes to the buildings, stopped using a few roads and agreed to not make any new construction within 100 metres of the forest reserve.

The same year, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India pulled up the state’s forest department for not stopping Isha’s illegal constructions despite knowing about them since 2012. The constructions had been done without required approvals from HACA, the CAG reiterated.

Responding to the CAG’s report, Isha claimed they have received HACA approval for all their constructions on March 16, 2017. But the committee formed by the principal chief conservator to inspect the Isha campus and decide on its application was formed only on March 17, and submitted its report on March 29. In fact, it wasn’t until April 4 that the principal chief conservator made a conditional recommendation to the town and country planning to grant post-construction approval to Isha. The planning department, in turn, directed its regional deputy director in Coimbatore on May 3 to issue post-construction to Isha provided they paid the required fees and adhered to the conditions of the forest department. How then is it possible for the HACA to have approved Isha’s constructions on March 16?

Isha refused to respond to this and other specific allegations. Replying to an email by Newslaundry seeking comment, a spokesperson for the foundation warned, “While your assumptions and presumptions are not material to us, should you slander the foundation, you will do so at your own risk.”

Tamil Nadu doesn’t have a mechanism to give post-construction clearance. The town and country planning department can regularise a construction post facto but only if its conditions are met. It can’t give an environmental clearance, however.

Basavraju, principal chief conservator at the time, wouldn’t answer our questions about recommending post-construction approval for Isha’s structures. His successor, Durairasu, who filed the status report to the National Green Tribunal, said, “Conditions were levied and then only recommendations were made. I don’t know whether they followed the conditions. As per my knowledge they have not received permission from HACA until now.”

Rajamani, who as Coimbatore’s district collector heads HACA, said he didn’t want to talk about the agency’s approval to Isha. “You can write whatever you want,” he added.

The secret of Johnson’s success lies in his break with Treasury dominance

The Conservative party’s growing electoral dominance in non-metropolitan England, so starkly re-emphasised by results in the north-east, has been attributed to various causes. Brexit and the popularity of Boris Johnson both count for a great deal. But while Labour is busy telling voters how much it deserved to lose, this is only half the picture. A major part of Johnson’s appeal is the way he has escaped the shadow cast by one of Britain’s three most significant political figures of the past 45 years: not Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair, but Gordon Brown.

The 1994 meeting between Blair and Brown at the Granita restaurant in Islington, north London, shortly after John Smith’s death, is the founding myth of New Labour: the moment when Brown agreed to let Blair stand for the leadership, on certain conditions. In addition to Blair’s much disputed commitment to serve only two terms in office should he become prime minister, there was also his promise that Brown, as chancellor, would get control over the domestic policy agenda. At least the second of these commitments was honoured, resulting in a situation where, from 1997 to 2007, the Treasury held an overwhelming dominance over the rest of Whitehall, while Brown was implicitly unsackable.

But, together with his adviser Ed Balls, Brown was also the architect of a new apparatus of economic policymaking designed for the era of globalisation. The central problem that Balls and Brown confronted was how to build the capacity for higher levels of social spending, while also retaining financial credibility in an age of far more mobile capital than any confronted by previous Labour governments. The fear was that, with financial capital able to cross borders at speed, a high-spending government might be viewed suspiciously by investors and lenders, making it harder for the state to borrow cheaply. The first part of their answer endures to this day: operational independence was handed to the Bank of England, accompanied by an inflation target. No longer could politicians seek to win elections by cutting interest rates, a move that aimed to win the trust of the markets.

On top of this, Brown also introduced a culture of almost obsessive fiscal discipline, as if the bond markets would attack the moment he showed any flexibility – the same paranoia that shaped Clintonism. His “golden rule”, outlined in his first budget, stated that, over the economic cycle, the government could borrow only to invest, not for day-to-day spending. The Treasury governed the rest of Whitehall according to a strict economic rubric, demanding every spending proposal was audited according to orthodox neoclassical economics.

Balls later wrote that their thinking had been guided by an influential 1977 article, Rules Rather than Discretion, in which two economists, Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott, sought to demonstrate that policymakers will produce far better economic outcomes if they stick rigidly to certain principles and heuristics of policy, rather than seeking to intervene on a case-by-case basis. Brown’s robotic persona and his mantra of “prudence” conveyed a programme that was so focused on policy as to be oblivious to more frivolous aspects of politics.

Elements of this Brownite machine remained in place during the David Cameron-George Osborne years: a chancellor acting as a kind of parallel prime minister, transforming society through force of cost-benefit analysis, only now the fiscal tide was going out rather than in. Even “Spreadsheet Phil” Hammond sustained the template as far as he could, in the face of ever-rising attacks from the Brexit extremists in his own party. The point is that, from 1997 to 2019, the government largely meant the Treasury. Those powers that are so foundational for the modern nation state – to tax, borrow and spend – were the basis on which governments asked to be judged, by voters and financial markets.

Various things have happened to weaken the Treasury’s political authority over the past five years, though – significantly – none of these has yet seemed to weaken the government’s credibility in the eyes of the markets. First, there was the notorious cooked Brexit forecast published in May 2016, predicting an immediate recession, half a million job losses and a house price crash, should Britain vote to leave. The referendum itself, a mass refusal to view the world in terms of macroeconomics, meant there could be no going back to a world in which politics was dominated by economists.

Consider how different things are now from in Brown’s heyday. Johnson’s first chancellor, Sajid Javid, lasted little more than six months in the job, resigning after one of his aides was sacked by Dominic Cummings without his knowledge. His second, Rishi Sunak, may have high political ambitions and approval ratings, but scarcely forms the kind of double-act with Johnson that Brown did with Blair, or Osborne with Cameron. Johnson’s cabinet is notable for lacking any obvious next-in-line leader.

What’s more interesting are the parts of Whitehall that have suddenly risen in profile under Johnson: communities and local government under Robert Jenrick, and the Department for Digital, Culture Media and Sport under Oliver Dowden. With the “levelling up” agenda of the former, (manifest in such pork barrel politics as the Towns Fund) and the “culture war” agenda of the latter (evident in attacks on the autonomy of museums), a new vision of government is emerging, one that is no longer afraid of expressing cultural favouritism or fixing deals. Balls and Brown were inspired by “rules rather than discretion”; now there’s no better way to sum up Jenrick’s disgraceful governmental career to date than “discretion rather than rules”.

In the background, of course, are the unique fiscal and financial circumstances produced by Covid, in which all notions of prudence have been thrown out of the window. With the Bank of England buying most of the additional government bonds issued over the last 15 months (beyond the wildest imaginings of Balls and Brown), and with the cost of borrowing close to zero, the rationale for strict fiscal discipline or austerity has currently evaporated. Paradoxically, a situation in which the Treasury can find an emergency £60bn to pay the country’s wages makes for a popular chancellor, but may make for a less powerful Treasury.

Amid all this, Labour is left in an unenviable position, which is in many ways deeply unfair. So long as the Tories are associated with Brexit, England and Johnson, the voters don’t expect them to exercise any kind of discipline, fiscal or otherwise. Meanwhile, Labour remains associated with a Treasury worldview: technocratic, London-centric, British not English, rules not discretion. What’s doubly unfair is that, thanks to the serial fictions of Osborne and the Tory press from 2010 onwards that Labour had “spent all the money”, it is not even viewed as economically trustworthy. In the end, it turned out that public perceptions of financial credibility were largely shaped by political messaging and media narratives, not by adherence to self-imposed fiscal rules.

In the eyes of party members, New Labour will be for ever tarred by Blair and Iraq. In the eyes of much of the country, however, it will be tarred by some vague memory of centralised Brownite spending regimes. The fact that Labour receives so little credit for Brown’s undoubted successes as a spending chancellor is due to many factors, but ultimately consists in the fact that the technocratic, Treasury view of the world was never adequately translated into a political story. Osborne simply presented himself as the inheritor of a centralised “mess” that needed cleaning up.

The recent elections demonstrated that all political momentum is now with the cities and nations of Britain: the Conservatives in leave-voting England, Andy Burnham in Manchester, the SNP in Scotland, Labour in Wales. Rather than making weak gestures towards the union jack or against London, Labour needs to think deeply about the kind of statecraft and policy style that is suited to such a moment, so as to finally leave the world of Granita and “golden rules” behind.

Tuesday, 18 May 2021

Monday, 17 May 2021

Why the suspicion on China’s Wuhan lab virus is growing

Tara Kartha in The Print

It’s been nearly eighteen months since the coronavirus brought the world on its knees, with India in the middle of a deadly second wave that is claiming 4,000 lives daily on an average. No one can tell when this will end. But it is possible to probe how this catastrophe began, and China’s role in it. Fortunately, even as cover ups go on. Several reports are out in the public domain and anybody who isn’t afraid of speaking the truth should be able to connect the dots.

One report out is that of the Independent Panel, set up by a resolution of the 73rd World Health Assembly. The specific mission of the committee was to review the response of the World Health Organization (WHO) to the Covid outbreak and the timelines relevant. In other words, it was never meant to be an inquisition on China. And it wasn’t. Not by a long chalk. It went around the core question of the origin of the virus, even while indulging in what seems to be pure speculation. Then there are two recent publications investigating the origin of the virus, which are worthy of note. Neither are written by sage scientists, but by analysts viewing the whole sequence of events through the prism of intelligence. Which means that these efforts skip the big words, and get to the facts. Collate all these different sources, add a little more of the background colour, and you start to get the big picture.

Is this biological warfare?

The need to find out the truth becomes urgent as the situation worsens, for instance with dangerously high death rates in Aligarh Muslim University, where there is now speculation whether the deaths could be linked to a separate strain. There are arguments that India’s second wave could be a deliberate one, especially since the ‘double mutant’ has not hit any of its neighbours. Such speculation is likely to rise, given that China has now effectively closed any possibility of withdrawal from Ladakh, and the Chinese economy goes from strength to strength, growing a record 18.3 per cent in the first quarter of the new financial year. Unsurprisingly, even world leaders, like Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro, have linked the pandemic to biological warfare.

Arising from this is the biggest potential danger: someone may decide to respond in kind in a bid to fix Beijing. That’s how intelligence operations work. After all, major countries haven’t been funding their top secret labs for nothing. In any scenario, there’s some serious trouble ahead, especially since the Narendra Modi government seems to be more intent on playing down the crisis than addressing it.

The Independent Panel

The panel’s mandate is set out clearly in the May 2020 resolution, which calls for “a stepwise process of impartial, independent and comprehensive evaluation…to review experience gained and lessons learned from the WHO-coordinated international health response to COVID-19…” and thereafter provide recommendations. This the panel undoubtedly did.

The 13-member panel included former Prime Minister of New Zealand Helen Clark, former President of Liberia who has core expertise in setting up health care after Ebola, an award winning feminist, a former WHO bureaucrat, and a former Indian health secretary, who had six months experience in handling the first Covid wave, was on innumerable panels on health, and in the manner of civil servants in this country, also did a stint in the Ministry of Defence, not to mention the World Bank. The Indian representative certainly gives the whole exercise the imprimatur of legality, given hostile India-China relations. And finally, Zhong Nanshan who was advisor to the Chinese government during the Wuhan outbreak, and who received the highest State honour of the Medal of the Republic from his President—Xinhua describes him as a “brave and outspoken” doctor.

The WHO also lists Peng Liyuan as a Goodwill Ambassador, describing her as a famous opera singer. She is the wife of President Xi Jinping. It’s,therefore, entirely unsurprising that while the panel diligently shows WHO the sources of early warning, it makes a vague case on the origins of the virus, noting that while a species of bat was “probably” the host, the intermediate cycle is unknown. Most astonishingly, the committee states that the virus “may already have been in circulation outside China in the last months of 2019”. No evidence for that either. The overall tenor of the report is that it would take years to sort all this out.

There is only one paragraph of note from the point of view of those seeking the truth.

The panel’s report states that less than 55–60 per cent of early cases had been exposed to the wet markets, and that the area merely “amplified” the virus. In other words, the market, with its hundreds of exotic wildlife, could not have been the source. It, however, carefully notes that the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) sequenced the entire genome of the virus almost within weeks, and later provided this to a public access source. The report praises the diligence of clinicians who managed to isolate the virus within a short time. That’s wonderful all right. No question. But it doesn’t at all address the question whether those diligent researchers were also experimenting on the virus.

That troubling question

These assessments by the Independent Panel are now, however, being questioned, leading to bits of intelligence being pieced together from within a country that would put the term ‘Iron curtain’ to shame. An earlier WHO study on the virus’ origin was roundly condemned by a group of countries,including the US, Australia, Canada and others (not India) as being duplicitous in the extreme.

In January 2021, the US Department of State released a Fact Sheet on activity of WIV, which is entirely based on intelligence. That factsheet is damning, indicating that several researchers at the institute had fallen ill with characteristics of the Covid virus, thus showing up senior Chinese researcher Shi Zhengli’s claim that there was “zero infection” in the lab. The lab was the centre of research of the SARS virus since its first outbreak, including on ‘RaTG13’ virus found in bats, and which is 96 per cent similar to the present virus SARS-COV-2. Worst, it also pointed out that “the United States has determined that the WIV has collaborated on publications and secret projects with China’s military. The WIV has engaged in classified research, including laboratory animal experiments, on behalf of the Chinese military since at least 2017”.

That’s intelligence. Now for the analysis — the two recent publications probing the virus’ origin.

Disaggregating the facts

One analytical article is published in the prestigious Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Another is a paper by the equally reputed Begin Sadat Centre for Strategic Studies. Both are a careful collation of facts, and establish the following.

The paper by Begin Sadat Centre brings out additional information that bolsters the US Fact Sheet. It appears that the US had been able to get a ‘source’ from WIV directly, and that another Chinese scientist had defected to an unknown European country. That led directly to information on the military side of the programme. The study also quotes David Asher, who led the Department of State investigation. Asher observes that the WIV had two campuses, not one, as popularly believed. This was known by the Indian authorities for years, but does not seem to have been put about. Asher also adds that all mention of the SARS virus was dropped from the institute’s publicly admitted biological “defence programmes” by 2017 at the same time when the Level 4 lab kicked off operations.

Even more surprising was that an adjacent facility had already administered vaccines to its senior faculty in March 2020 itself. That doesn’t suggest an accident. That suggests a program that was designed to kill, and for which vaccines were already under research. Then there damning studies stated: “There are plenty of indications in the sequence itself that [the initial pandemic virus] may have been synthetically altered. It has the backbone of a bat [coronavirus], combined with a pangolin receptor binder, combined with some sort of humanized mice transceptor. These things don’t actually make sense (and) …..the odds this could be natural are very low… [but this is attainable] through deliberate scientific ‘gain of function research” that was going on at the WIV.

There is no doubt that ‘gain of function’ research is practised in biological research labs world over, resulting in, sometimes, dangerous incidents. This type of research involves in-crossing viruses, ostensibly to gain knowledge on how to battle the disease from within. In these cases, it’s almost impossible to decide where the ‘defence’ aspect leaches into an offensive capability. That these findings were from US scientists who were ‘fearful’ of being quoted shows not just the extent of Beijing’s clout in university research and funding, but also a high degree of restraint. Biological research is almost never talked about.

The denials begin

Biological research and the secrecy around it is the aspect of focus in Nicholas Wade’s article published in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. As he writes, from the beginning, there was denial at the highest levels from some unexpected quarters. The first was in The Lancet— one of the oldest journals of medical research—by a group of authors in March 2020, when the pandemic had just broken out. Even to a layman, it would have seemed that it was far too early for the group of authors to contemptuously dismiss ‘conspiracy theories’ that the virus was not of a natural origin.

It turns out that The Lancet letter was drafted by Peter Daszak, President of the EcoHealth Alliance of New York, who’s organisation funded corona virus research at the Wuhan lab. As is pointed out in Wade’s article, any revelation of such a connection would have been criminal to say the least, if it was proved that the virus did escape from the lab. Unsurprisingly, Daszak was also part of the WHO team investigating the origins of the virus.

Another burst of outrage came from a group of professors who also hurried to disprove, in an article, the ‘lab created’ theory on the grounds – simply put – that it was not of the most probably calculated design. The lead author Kristian G Anderson is from the Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, which specialises in biomedical research. It also has partnerships with Chinese labs and pharma companies. None of that is criminal. Especially when Scrippsis already in financial distress at the time. Besides, such collaborations are not restricted to just US labs. See, for instance, an account of Australian doctor Dominic Dwyer, who was part of the first WHO study, and who dismissed without any evidence presented that the virus had leaked from a lab.

Dwyer’s claim that the Wuhan lab seems to have been run well, and that nobody from the facility seemed to have fallen sick has now been disputed. Evidence of a dangerous virus escaping a lab – as it has in the past on what he calls “rare” occasions – would mean a death blow to labs everywhere. Funding is, after all, hard to come by. Then there is the nice hard cash involved. The Harvard professor Dr Charles Leiber who was arrested, together with two other Chinese, for collaborating quietly with the Wuhan University of Technology (WUT), was being paid roughly $50,000 per month, living expenses of up to 1,000,000 Chinese Yuan (approximately $158,000) and awarded $1.5 million to establish a research lab at WUT. He was also asked to ‘cultivate’ young teachers and Ph.D. students by organising international conferences.

It’s all very pally and friendly, and a lot of money is involved. The end result? A virus out of hell, that seems not to affect the Chinese as its economy powers ahead and shifts its weight more comfortably into its rising position in the global order.

How to avoid the return of office cliques

Some managers are wary of telling staff that going into a workplace has networking benefits writes Emma Jacobs in The FT

Sunday, 16 May 2021

Islamophobia And Secularism

Prime Minister Imran Khan frequently uses the term ‘Islamophobia’ while commenting on the relationship between European governments and their Muslim citizens. Khan has often been accused of lamenting the treatment meted out to Muslims in Europe, but remaining conspicuously silent about cases of religious discrimination in his own country.

Then there is also the case of Khan not uttering a single word about the Chinese government’s apparently atrocious treatment of the Muslim population of China’s Xinjiang province.

Certain laws in European countries are sweepingly described as being ‘Islamophobic’ by Khan. When European governments retaliate by accusing Pakistan of constitutionally encouraging acts of bigotry against non-Muslim groups, the PM bemoans that Europeans do not understand the complexities of Pakistan’s ‘Islamic’ laws.

Yet, despite the PM repeatedly claiming to know the West like no other Pakistani does, he seems to have no clue about the complexities of European secularism.

Take France for instance. French secularism, called ‘Laïcité’ is somewhat different than the secularism of various other European countries and the US. According to the contemporary scholar of Western secularism, Charles Taylor, French secularism is required to play a more aggressive role.

In his book, A Secular Age, Taylor demonstrates that even though the source of Western secularism was common — i.e. the emergence of ‘modernity’ and its political, economic and social manifestations — secularism evolved in Europe and the US in varying degrees and of different types.

Secularism in the US remains largely impersonal towards religion. But in France and in some other European countries, it encourages the state/government to proactively discourage even certain cultural dimensions of faith in the public sphere which, it believes, have the potential of mutating into becoming political expressions.

Nevertheless, to almost all prominent philosophers of Western democracy across the 19th and 20th centuries, the idea of providing freedom to practise religion is inherent in secularism, as long as this freedom is not used for any political purposes.

According to the American sociologist Jacques Berlinerblau in A Call to Arms for Religious Freedom, six types of secularism have evolved. The American researcher Barry Kosmin divides secularism into two categories: ‘soft’ and ‘hard’. Most of Berlinerblau’s types fall in the ‘soft’ category. The hard one is ‘State Sponsored Atheism’ which looks to completely eliminate religion. This type was practised in various former communist countries and is presently exercised in China and North Korea. One can thus place Laïcité between Kosmin’s soft and hard secular types.

The existence of what is called ‘Islamophobia’ in secular Europe and the US has increasingly drawn criticism from various quarters. According to the French author Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, the term is derived from the French word ‘islamophobie’ that was first used in 1910 to describe prejudice against Muslims.

L.P. Sheridan writes in the March 2006 issue of the Journal of Interpersonal Violence that the term did not become widely used till 1991. According to Roland Imhoff and Julia Recker in the Journal of Political Psychology, a wariness had already been building in the West towards Muslims because of the aggressively anti-West ‘Islamic’ Revolution in Iran in 1979, and the violent backlash in some Muslim countries against the publication of the novel Satanic Verses by the British author Salman Rushdie in 1988.

Islamophobia is one of the many expressions of racism towards ‘the other’. Racisms of varying nature have for long been present in Europe and the US. Therefore Imhoff and Recker see Islamophibia as “new wine in an old bottle.” It is a relatively new term, but one that has also been criticised.

Discrimination against race, faith, ethnicity, caste, etc., is present in almost all countries. But its existence gets magnified when it is present in countries that describe themselves as liberal democracies.

Whereas Islamophobia is often understood as a phobia against Islam, there are also those who find this definition problematic. To the term’s most vehement critics, not only has it overshadowed other aspects of racism, of which there are many, it is also mostly used by ‘radical Muslims’ to curb open debate.

In a study, the University of Northampton’s Paul Jackson writes that the term should be replaced with ‘Muslimphobia’ because the racism in this context is aimed at a people and not towards the faith, as such. However, he does add that the faith too should be open for academic debate.

In an essay for the 2016 anthology The Search for Europe, Bichara Khader writes that racism against non-white migrants in Europe intensified in the 1970s because of a severe economic crisis. Khader writes that this racism was not pitched against one’s faith.

According to Khader, whereas this meant that South Asian, Arab, African and Caribbean migrants were treated as an unwanted whole based on the colour of their skin, from the 1980s onwards, the Muslims among these migrants began to prominently assert their distinctiveness. As the presence of veiled women and mosques grew, this is when the ‘migration problem’ began to be seen as a ‘Muslim problem’.

The Muslim diaspora in the West began to increasingly consolidate itself as a separate whole. Mainly through dress, Muslim migrants began to shed the identity of their original countries, creating a sort of universality of Muslimness.

But this also separated them from the non-Muslim migrant communities, who were facing racial discrimination as well. Interestingly, this imagined universality of Muslimness was also exported back to the mother countries of Muslim migrants.

Take the example of how, in Pakistan, some recent textbooks have visually depicted the dress choices of Pakistani women. They are almost exactly how some second and third generation Muslim women in the West imagine a woman should dress like.

But there was criticism within Pakistan of this depiction. The critics maintain that the present government was trying to engineer a cultural type of how women ought to dress in a country where — unlike in some other Muslim countries — veiling is neither mandatory nor banned. This has only further highlighted the fact that identity politics in this context in Pakistan is being influenced by the identity politics being flexed by certain Muslim groups in the West.

Either way, because of the fact that it is a recent phenomenon, identity politics of this nature is not organic as such, and will continue to cause problems for Muslims within and away.