'People will forgive you for being wrong, but they will never forgive you for being right - especially if events prove you right while proving them wrong.' Thomas Sowell

Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Marx. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Marx. Show all posts

Thursday, 22 August 2024

Monday, 25 September 2023

Saturday, 13 November 2021

Sunday, 31 October 2021

Friday, 20 August 2021

Thursday, 27 May 2021

Saturday, 8 May 2021

Monday, 3 May 2021

Pinarayi Vijayan is Kerala’s ‘Modi in a mundu’

Jyoti Malhotra in The Print

In his home village of Pinarayi in north Kerala’s Kannur district, Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan arrived one early April morning to inaugurate a Yoga-cum-Kalaripayattu camp at the local convention centre. He sat right through the exploits of enthusiastic children lining up to show off their skills and awarded long-haired Yoga and Kalari teachers spouting the values of the ancient, Hindu spiritual and martial arts disciplines, raising his hand occasionally to bless them all.

---

If there wasn’t a huge red hoarding outside the centre, saying ‘Captain’ picturing Vijayan in his spotless white ‘mundu-veshti’ and red CPI(M) flags and bunting leading towards it, you would be forgiven for thinking that a transformation of the state’s iron-fisted Communist leader was in the offing.

But this is Kerala, dotted with hundreds of temples and churches and mosques and for the first time since 1977, won by a Communist party for the second time running. In the intervening years, the state has always alternated between the Left Democratic Front and the Congress-led United Democratic Front.

This time around, the 75-year-old Pinarayi Vijayan has created history not just by keeping the state, with 99 seats — eight more seats than won by his bete noire in the party, former chief minister V.S. Achuthanandan in 2011 — but by restricting the UDF to 41 seats.

For Kerala, the question of “who is Pinarayi Vijayan” is irrelevant. The state knows him as a strong CPI(M) leader who joined the party the year it split in 1964, became the state president of the Kerala Students Federation, was arrested and tortured during the Emergency, had a public spat with fellow Politburo member V.S. Achuthanandan in 2007 over the latter’s demolition drive against illegal resorts in the Munnar hills — for which both were suspended — and remains unapologetic about the fact that he won’t let much come in the way of building the party organisation.

With this victory, he has proved his worth not just to the party, but also to the national opposition. CPI(M) general secretary Sitaram Yechury’s roots in the party are seen to be linked to Bengal, because of his acknowledged proximity to former chief minister Jyoti Basu, although he is also seen as a VS (Achuthanandan) protégé — it was VS who had helped deliver Yechury to the top job at the party congress in 2015.

But the Left has been totally wiped out in Bengal, down to zero from 76 seats in the last election, and it lost Tripura back in 2018. Today, in only one corner of India, it is because of Pinarayi Vijayan that the hammer-and-sickle is still flying.

‘Mundu udutha Modi’

Vijayan’s political strength is magnified by the fact that he has prevented the BJP from winning even one seat — in the outgoing Assembly, the BJP had the Nemom constituency on the outskirts of Thiruvananthapuram in its kitty.

And yet, for someone as seemingly hardline as Vijayan, he has for years been dogged by a pro-corporate image. In 1997, when he was electricity minister, Vijayan converted an MoU with the Canadian firm SNC Lavalin into a fixed price deal for supply of equipment and services to renovate projects for Rs 239.81 crore.

The 2007 spat with VS took place because Vijayan wanted the resorts to stay.

In February 2020, his government signed an MoU with a US-based company, EMCC Global Consortium LCC, for an upgrade and promotion of deep sea fishing in Kerala, provoking Congress leader Ramesh Chennithala to say the LDF government was “cheating the fishers”. Also last year, he allowed the Kerala Infrastructure Investment Board Fund to issue masala bonds at the London Stock Exchange so funds could be raised from the market to fund welfare activities in the state.

Interestingly, Vijayan is widely known across the state as “mundu udutha Modi” or “Modi in a mundu (similar to dhoti or lungi)”, because of the manner in which he has, systematically, finished off his rivals.

There was VS, of course, who wanted to be chief minister in 2016, but even Yechury realised that it was better to give the state to Vijayan than to the warm and fuzzy “Fidel Castro of Kerala”. There is the former industries minister E.P. Jayarajan, a former Vijayan confidant from Kannur who has retired from politics because he was denied a ticket in this election. Kodiyeri Balakrishnan, fellow Politburo member and rival, stepped down because of cases against his son Bineesh. And outgoing finance minister Thomas Isaac, who reinvented KIIFB, was not allowed to contest because of the two-term rule.

In an interview that early April morning, after he was done with the Yoga and Kalari event in Pinarayi village, I asked the chief minister why he was called the Narendra Modi of Kerala. He laughed softly, and said: “I do not know what kind of person Narendra Modi is. The people of Kerala know what kind of person I am for many years. I don’t have to emulate Narendra Modi. I have my own style and methods. Modi might have his own style.”

Certainly, unlike Modi, Pinarayi Vijayan doesn’t pretend to have a vaulting national ambition. Moreover, unlike the former leaders of the former Soviet Union, he understands that it is important to first protect the home turf, and then think of expanding Communism abroad.

‘Communism with Malayali characteristics’

In the interview, he believed it was important for the Opposition to come together to take on the BJP and Modi, and insisted there was no contradiction in the Left fighting against Congress in Kerala and alongside the Congress in West Bengal.

“There is a unique situation in West Bengal. We took a stand keeping in mind this unique situation. This does not mean the Congress has been absolved of its sins,“ he said.

Certainly, multi-religious Kerala’s uniqueness stems from the fact that it was the first democratic state in the world to elect a Communist government in 1957. Cut to 2021, when Pinarayi Vijayan makes history by beating anti-incumbency and bringing a Communist government to power for the second time in a row.

Asked why Kerala continued to choose Communist governments when the Soviet Union broke itself up in 1991, Vijayan told ThePrint that the CPM was able to “correctly analyse and speak out within the party” about what was happening in the Soviet Union…we were able to carefully preserve the CPM. We were able to take the stand that Marxism-Leninism was right. Fact is, in Kerala, the CPM & Communist parties were strong before and continue to be strong.”

In Vijayan’s mind, Marxism-Leninism is about both Marx and market, just another way into the hearts of people. That’s why Yoga camps as well as the London Stock Exchange are par for the course.

As Pinarayi Vijayan takes the reins of Kerala again, this is a description he would be comfortable with.

Here's Why Pinarayi Vijayan Can't Be Called a 'Modi in a Mundu'

P Raman in The Wire

The CPI(M)-led Left Democratic Front is set to retain power in Kerala, with the trends projecting it as leading or having won at least 94 of the 140 assembly seats.

The LDF victory will curb a four decade-old trend of the state electing communist and Congress-headed governments alternatively.

Two years ago, soon after the Left Front suffered a stunning defeat in the 2019 parliamentary elections, prominent Malayalam daily Mathrubhumi carried a series of edit page articles.

The commentators were in a celebratory mood. One of them gleefully concluded that religion and spiritualism – Sabarimala – had finally triumphed over materialism and Marxism. The commentators concluded that Marxism is archaic, and communists neither change nor learn from past mistakes. Thus, they said, the Left rout in its last sanctuary – they got just one out of 20 Lok Sabha seats – heralded the extinction of communism in Indian peninsula.

I was born and brought up in a communist village in old Malabar. I am familiar with the lifestyles and practices of early communists. To say they have not changed is sheer moonshine. Most early communist workers were scions of landlord families. They left their comforts and moved from village to village, spreading Marxian ideals. They lived on cheap tea without milk and dal vada, like a romanticised proletariat.

Abnegation and monkish life were part of the communist culture. Perhaps it was derived from the Gandhian ethos. Members took the party’s permission even on personal matters like marriage. In early 1960s, I remember Indrajit Gupta, then a young trade unionist, arriving at Calcutta’s 33, Alimuddin Street in a Fiat car with a red flag on it. It was a cultural shock – a trade union worker travelling in a car. It was explained that Gupta found it difficult to reach half dozen trade union functions by travelling in trams. So some richer trade unionists pooled funds and bought an old, creaking Fiat.

Six decades later, I found half a dozen private cars parked at a CPI(M) area committee office in remote Kerala. Even middle level CPI(M) leaders move in their own cars. They have none of the qualms that their 20th century comrades felt.

How can you say the communists never change? Before 1952, the parliamentary route was ‘revisionism’ for communists. The ‘national bourgeoisie’ debate continued for another two decades. For decades, editorial writers attributed the communist success to foreign money. Today’s communists are shorn of all such baggage.

So how has the Left managed to romp back with such a huge majority?

The most simplistic explanation is that the communists have also become another regional party under a charismatic autocrat. Thus, Pinarayi is called a ‘mundututta Modi’ or ‘Modi in a mundu’.

This strongman cult, like Modi’s, has clicked with the people.

Pinarayi Vijayan, who was the general secretary of the Kerala CPI(M) for 17 years, is the party’s senior most leader – barring, of course, the 97-year-old retired veteran V.S. Achuthanandan. Vijayan has a domineering say in the party organisation and the government he heads. But is this enough to call him a ‘Modi in a mundu?’

Is it true that Kerala communists, in their desperate bid to remain, have relevant opted for an authoritarian model?

The first parameter to gauge the degree of authoritarianism in a political party is the level of its internal democracy. In India, CPI(M) and CPI are the only political parties that hold regular elections as per their constitution. For over a decade, all members of the Kerala state committee (as also other elective posts) were chosen by secret ballots at the state party conference. The results with details such as the number of votes each contestant got were released soon after the counting. All this under sharp media glare and endless interpretations.

As per the BJP constitution, its national executive must meet once in every quarter and national council every year. Under the pre-Modi BJP, the two bodies did meet at regular intervals. How many times did the NE and NC met during the seven years under Modi? Elected autocrats – a term used by the Sweden-based V-Dem to describe the Modi regime – never tolerate a lively, functional party organisation.

The other parameter to measure authoritarianism is free internal debates.

For an authoritarian populist, the party must function as his or her appendage. What about the ‘Modi in a mundu?’ In the past two years, AKG Bhawan (the Kerala CPI(M) headquarters) made at least half a dozen interventions. It formally asked the government to reverse many of its decisions. Sections of the media interpreted such interventions as grassroots rumblings. Will any BJP committee – NE, NC or parliamentary party – dare to make such critical remarks about Modi or his actions?

Sample these:

The CPI(M) secretariat on February 20, 2021, attended by Pinarayi Vijayan, directed the latter to initiate minister-level discussions with agitating job-seekers. It said the opposition should not be allowed to take political advantage of the agitation. And Vijayan promptly did.

The CPI(M) state secretariat, after its meeting, observed that the continuing controversy over the gold smuggling has affected the party’s image and that it is a major setback to the party. It asked the chief minister to take corrective measures.

The CPI(M) secretariat on May 25, 2019, asserted that the government’s Sabarimala policy had badly affected the party’s performance in the Lok Sabha elections. It asked the government for a relook. Vijayan obliged.

Following pressure from within the CPI(M), Vijayan (on November 4, 2019) said that the government did not support the police’s move to invoke the UAPA against workers for Maoist links.

A closer look will reveal that AKG Bhawan acted as an alert watchdog and monitor rather than the CMO’s appendage. Will hard-headed ‘elected autocrats’ like Narendra Modi tolerate such interventions?

Pinarayi came closest to the personality cult trap when his image makers began projecting him as ‘Captain Pinarayi’ – for his leadership in tackling the floods and the Nipah outbreak. This came in for sharp criticism within the party and soon the CPI(M) leadership cried a halt to it – first, senior leader Kodiyeri Balakrishnan and then Prakash Karat.

“Pinarayi is our ‘comrade’, not ‘captain’,” Balakrishnan said. Soon Vijayan himself washed his hands off the ‘captain’ epithet, in what was yet another example of the the CPI(M)’s embedded corrective mechanism working.

In his home village of Pinarayi in north Kerala’s Kannur district, Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan arrived one early April morning to inaugurate a Yoga-cum-Kalaripayattu camp at the local convention centre. He sat right through the exploits of enthusiastic children lining up to show off their skills and awarded long-haired Yoga and Kalari teachers spouting the values of the ancient, Hindu spiritual and martial arts disciplines, raising his hand occasionally to bless them all.

--- Also watch

---

If there wasn’t a huge red hoarding outside the centre, saying ‘Captain’ picturing Vijayan in his spotless white ‘mundu-veshti’ and red CPI(M) flags and bunting leading towards it, you would be forgiven for thinking that a transformation of the state’s iron-fisted Communist leader was in the offing.

But this is Kerala, dotted with hundreds of temples and churches and mosques and for the first time since 1977, won by a Communist party for the second time running. In the intervening years, the state has always alternated between the Left Democratic Front and the Congress-led United Democratic Front.

This time around, the 75-year-old Pinarayi Vijayan has created history not just by keeping the state, with 99 seats — eight more seats than won by his bete noire in the party, former chief minister V.S. Achuthanandan in 2011 — but by restricting the UDF to 41 seats.

For Kerala, the question of “who is Pinarayi Vijayan” is irrelevant. The state knows him as a strong CPI(M) leader who joined the party the year it split in 1964, became the state president of the Kerala Students Federation, was arrested and tortured during the Emergency, had a public spat with fellow Politburo member V.S. Achuthanandan in 2007 over the latter’s demolition drive against illegal resorts in the Munnar hills — for which both were suspended — and remains unapologetic about the fact that he won’t let much come in the way of building the party organisation.

With this victory, he has proved his worth not just to the party, but also to the national opposition. CPI(M) general secretary Sitaram Yechury’s roots in the party are seen to be linked to Bengal, because of his acknowledged proximity to former chief minister Jyoti Basu, although he is also seen as a VS (Achuthanandan) protégé — it was VS who had helped deliver Yechury to the top job at the party congress in 2015.

But the Left has been totally wiped out in Bengal, down to zero from 76 seats in the last election, and it lost Tripura back in 2018. Today, in only one corner of India, it is because of Pinarayi Vijayan that the hammer-and-sickle is still flying.

‘Mundu udutha Modi’

Vijayan’s political strength is magnified by the fact that he has prevented the BJP from winning even one seat — in the outgoing Assembly, the BJP had the Nemom constituency on the outskirts of Thiruvananthapuram in its kitty.

And yet, for someone as seemingly hardline as Vijayan, he has for years been dogged by a pro-corporate image. In 1997, when he was electricity minister, Vijayan converted an MoU with the Canadian firm SNC Lavalin into a fixed price deal for supply of equipment and services to renovate projects for Rs 239.81 crore.

The 2007 spat with VS took place because Vijayan wanted the resorts to stay.

In February 2020, his government signed an MoU with a US-based company, EMCC Global Consortium LCC, for an upgrade and promotion of deep sea fishing in Kerala, provoking Congress leader Ramesh Chennithala to say the LDF government was “cheating the fishers”. Also last year, he allowed the Kerala Infrastructure Investment Board Fund to issue masala bonds at the London Stock Exchange so funds could be raised from the market to fund welfare activities in the state.

Interestingly, Vijayan is widely known across the state as “mundu udutha Modi” or “Modi in a mundu (similar to dhoti or lungi)”, because of the manner in which he has, systematically, finished off his rivals.

There was VS, of course, who wanted to be chief minister in 2016, but even Yechury realised that it was better to give the state to Vijayan than to the warm and fuzzy “Fidel Castro of Kerala”. There is the former industries minister E.P. Jayarajan, a former Vijayan confidant from Kannur who has retired from politics because he was denied a ticket in this election. Kodiyeri Balakrishnan, fellow Politburo member and rival, stepped down because of cases against his son Bineesh. And outgoing finance minister Thomas Isaac, who reinvented KIIFB, was not allowed to contest because of the two-term rule.

In an interview that early April morning, after he was done with the Yoga and Kalari event in Pinarayi village, I asked the chief minister why he was called the Narendra Modi of Kerala. He laughed softly, and said: “I do not know what kind of person Narendra Modi is. The people of Kerala know what kind of person I am for many years. I don’t have to emulate Narendra Modi. I have my own style and methods. Modi might have his own style.”

Certainly, unlike Modi, Pinarayi Vijayan doesn’t pretend to have a vaulting national ambition. Moreover, unlike the former leaders of the former Soviet Union, he understands that it is important to first protect the home turf, and then think of expanding Communism abroad.

‘Communism with Malayali characteristics’

In the interview, he believed it was important for the Opposition to come together to take on the BJP and Modi, and insisted there was no contradiction in the Left fighting against Congress in Kerala and alongside the Congress in West Bengal.

“There is a unique situation in West Bengal. We took a stand keeping in mind this unique situation. This does not mean the Congress has been absolved of its sins,“ he said.

Certainly, multi-religious Kerala’s uniqueness stems from the fact that it was the first democratic state in the world to elect a Communist government in 1957. Cut to 2021, when Pinarayi Vijayan makes history by beating anti-incumbency and bringing a Communist government to power for the second time in a row.

Asked why Kerala continued to choose Communist governments when the Soviet Union broke itself up in 1991, Vijayan told ThePrint that the CPM was able to “correctly analyse and speak out within the party” about what was happening in the Soviet Union…we were able to carefully preserve the CPM. We were able to take the stand that Marxism-Leninism was right. Fact is, in Kerala, the CPM & Communist parties were strong before and continue to be strong.”

In Vijayan’s mind, Marxism-Leninism is about both Marx and market, just another way into the hearts of people. That’s why Yoga camps as well as the London Stock Exchange are par for the course.

As Pinarayi Vijayan takes the reins of Kerala again, this is a description he would be comfortable with.

-----Here's another view

Here's Why Pinarayi Vijayan Can't Be Called a 'Modi in a Mundu'

P Raman in The Wire

The CPI(M)-led Left Democratic Front is set to retain power in Kerala, with the trends projecting it as leading or having won at least 94 of the 140 assembly seats.

The LDF victory will curb a four decade-old trend of the state electing communist and Congress-headed governments alternatively.

Two years ago, soon after the Left Front suffered a stunning defeat in the 2019 parliamentary elections, prominent Malayalam daily Mathrubhumi carried a series of edit page articles.

The commentators were in a celebratory mood. One of them gleefully concluded that religion and spiritualism – Sabarimala – had finally triumphed over materialism and Marxism. The commentators concluded that Marxism is archaic, and communists neither change nor learn from past mistakes. Thus, they said, the Left rout in its last sanctuary – they got just one out of 20 Lok Sabha seats – heralded the extinction of communism in Indian peninsula.

I was born and brought up in a communist village in old Malabar. I am familiar with the lifestyles and practices of early communists. To say they have not changed is sheer moonshine. Most early communist workers were scions of landlord families. They left their comforts and moved from village to village, spreading Marxian ideals. They lived on cheap tea without milk and dal vada, like a romanticised proletariat.

Abnegation and monkish life were part of the communist culture. Perhaps it was derived from the Gandhian ethos. Members took the party’s permission even on personal matters like marriage. In early 1960s, I remember Indrajit Gupta, then a young trade unionist, arriving at Calcutta’s 33, Alimuddin Street in a Fiat car with a red flag on it. It was a cultural shock – a trade union worker travelling in a car. It was explained that Gupta found it difficult to reach half dozen trade union functions by travelling in trams. So some richer trade unionists pooled funds and bought an old, creaking Fiat.

Six decades later, I found half a dozen private cars parked at a CPI(M) area committee office in remote Kerala. Even middle level CPI(M) leaders move in their own cars. They have none of the qualms that their 20th century comrades felt.

How can you say the communists never change? Before 1952, the parliamentary route was ‘revisionism’ for communists. The ‘national bourgeoisie’ debate continued for another two decades. For decades, editorial writers attributed the communist success to foreign money. Today’s communists are shorn of all such baggage.

So how has the Left managed to romp back with such a huge majority?

The most simplistic explanation is that the communists have also become another regional party under a charismatic autocrat. Thus, Pinarayi is called a ‘mundututta Modi’ or ‘Modi in a mundu’.

This strongman cult, like Modi’s, has clicked with the people.

Pinarayi Vijayan, who was the general secretary of the Kerala CPI(M) for 17 years, is the party’s senior most leader – barring, of course, the 97-year-old retired veteran V.S. Achuthanandan. Vijayan has a domineering say in the party organisation and the government he heads. But is this enough to call him a ‘Modi in a mundu?’

Is it true that Kerala communists, in their desperate bid to remain, have relevant opted for an authoritarian model?

The first parameter to gauge the degree of authoritarianism in a political party is the level of its internal democracy. In India, CPI(M) and CPI are the only political parties that hold regular elections as per their constitution. For over a decade, all members of the Kerala state committee (as also other elective posts) were chosen by secret ballots at the state party conference. The results with details such as the number of votes each contestant got were released soon after the counting. All this under sharp media glare and endless interpretations.

As per the BJP constitution, its national executive must meet once in every quarter and national council every year. Under the pre-Modi BJP, the two bodies did meet at regular intervals. How many times did the NE and NC met during the seven years under Modi? Elected autocrats – a term used by the Sweden-based V-Dem to describe the Modi regime – never tolerate a lively, functional party organisation.

The other parameter to measure authoritarianism is free internal debates.

For an authoritarian populist, the party must function as his or her appendage. What about the ‘Modi in a mundu?’ In the past two years, AKG Bhawan (the Kerala CPI(M) headquarters) made at least half a dozen interventions. It formally asked the government to reverse many of its decisions. Sections of the media interpreted such interventions as grassroots rumblings. Will any BJP committee – NE, NC or parliamentary party – dare to make such critical remarks about Modi or his actions?

Sample these:

The CPI(M) secretariat on February 20, 2021, attended by Pinarayi Vijayan, directed the latter to initiate minister-level discussions with agitating job-seekers. It said the opposition should not be allowed to take political advantage of the agitation. And Vijayan promptly did.

The CPI(M) state secretariat, after its meeting, observed that the continuing controversy over the gold smuggling has affected the party’s image and that it is a major setback to the party. It asked the chief minister to take corrective measures.

The CPI(M) secretariat on May 25, 2019, asserted that the government’s Sabarimala policy had badly affected the party’s performance in the Lok Sabha elections. It asked the government for a relook. Vijayan obliged.

Following pressure from within the CPI(M), Vijayan (on November 4, 2019) said that the government did not support the police’s move to invoke the UAPA against workers for Maoist links.

A closer look will reveal that AKG Bhawan acted as an alert watchdog and monitor rather than the CMO’s appendage. Will hard-headed ‘elected autocrats’ like Narendra Modi tolerate such interventions?

Pinarayi came closest to the personality cult trap when his image makers began projecting him as ‘Captain Pinarayi’ – for his leadership in tackling the floods and the Nipah outbreak. This came in for sharp criticism within the party and soon the CPI(M) leadership cried a halt to it – first, senior leader Kodiyeri Balakrishnan and then Prakash Karat.

“Pinarayi is our ‘comrade’, not ‘captain’,” Balakrishnan said. Soon Vijayan himself washed his hands off the ‘captain’ epithet, in what was yet another example of the the CPI(M)’s embedded corrective mechanism working.

Saturday, 6 March 2021

Saturday, 5 May 2018

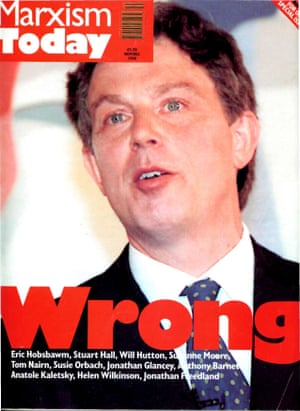

Is Marx still relevant 200 years later?

Amartya Sen in The Indian Express

How should we think about Karl Marx on his 200th birthday? His big influence on the politics of the world is universally acknowledged, though people would differ on how good or bad that influence has been. But going beyond that, there can be little doubt that the intellectual world has been transformed by the reflective departures Marx generated, from class analysis as an essential part of social understanding, to the explication of the profound contrast between needs and hard work as conflicting foundations of people’s moral entitlements. Some of the influences have been so pervasive, with such strong impact on the concepts and connection we look for in our day-to-day analysis, that we may not be fully aware where the influences came from. In reading some classic works of Marx, we are often placed in the uncomfortable position of the theatre-goer who loved Hamlet as a play, but wondered why it was so full of quotations.

Marxian analysis remains important today not just because of Marx’s own original work, but also because of the extraordinary contributions made in that tradition by many leading historians, social scientists and creative artists — from Antonio Gramsci, Rosa Luxemburg, Jean-Paul Sartre and Bertolt Brecht to Piero Sraffa, Maurice Dobb and Eric Hobsbawm (to mention just a few names). We do not have to be a Marxist to make use of the richness of Marx’s insights — just as one does not have to be an Aristotelian to learn from Aristotle.

There are ideas in Marx’s corpus of work that remain under-explored. I would place among the relatively neglected ideas Marx’s highly original concept of “objective illusion,” and related to that, his discussion of “false consciousness”. An objective illusion may arise from what we can see from our particular position — how things look from there (no matter how misleading). Consider the relative sizes of the sun and the moon, and the fact that from the earth they look to be about the same size (Satyajit Ray offered some interesting conversations on this phenomenon in his film, Agantuk). But to conclude from this observation that the sun and the moon are in fact of the same size in terms of mass or volume would be mistaken, and yet to deny that they do look to be about the same size from the earth would be a mistake too. Marx’s investigation of objective illusion — of “the outer form of things” — is a pioneering contribution to understanding the implications of positional dependence of observations.

The phenomenon of objective illusion helps to explain the widespread tendency of workers in an exploitative society to fail to see that there is any exploitation going on — an example that Marx did much to investigate, in the form of “false consciousness”. The idea can have many applications going beyond Marx’s own use of it. Powerful use can be made of the notion of objective illusion to understand, for example, how women, and indeed men, in strongly sexist societies may not see clearly enough — in the absence of informed political agitation — that there are huge elements of gender inequality in what look like family-oriented just societies, as bastions of role-based fairness.

There is, however, a danger in seeing Marx in narrowly formulaic terms — for example, in seeing him as a “materialist” who allegedly understood the world in terms of the importance of material conditions, denying the significance of ideas and beliefs. This is not only a serious misreading of Marx, who emphasised two-way relations between ideas and material conditions, but also a seriously missed opportunity to see the far-reaching role of ideas on which Marx threw such important light.

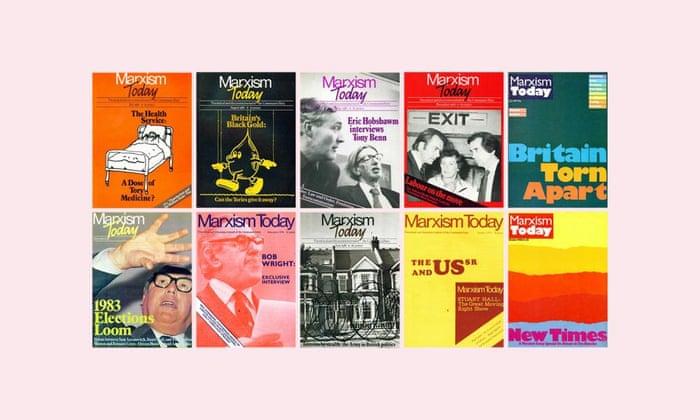

Let me illustrate the point with a debate on the discipline of historical explanation that was quite widespread in our own time. In one of Eric Hobsbawm’s lesser known essays, called “Where Are British Historians Going?”, published in the Marxist Quarterly in 1955, he discussed how the Marxist pointer to the two-way relationship between ideas and material conditions offers very different lessons in the contemporary world than it had in the intellectual world that Marx himself saw around him, where the prevailing focus — for example by Hegel and Hegelians — was very much on highlighting the influence of ideas on material conditions.

In contrast, the tendency of dominant schools of history in the mid-twentieth century — Hobsbawm cited here the hugely influential historical works of Lewis Bernstein Namier — had come to embrace a type of materialism that saw human action as being almost entirely motivated by a simple kind of material interest, in particular narrowly defined self-interest. Given this completely different kind of bias (very far removed from the idealist traditions of Hegel and other influential thinkers in Marx’s own time), Hobsbawm argued that a balanced two-way view must demand that analysis in Marxian lines today must particularly emphasise the importance of ideas and their influence on material conditions.

For example, it is crucial to recognise that Edmund Burke’s hugely influential criticism of Warren Hastings’s misbehaviour in India — in the famous Impeachment hearings — was directly related to Burke’s strongly held ideas of justice and fairness, whereas the self-interest-obsessed materialist historians, such as Namier, saw no more in Burke’s discontent than the influence of his [Burke’s] profit-seeking concerns which had suffered because of the policies pursued by Hastings. The overreliance on materialism — in fact of a particularly narrow kind — needed serious correction, argued Hobsbawm: “In the pre-Namier days, Marxists regarded it as one of their chief historical duties to draw attention to the material basis of politics. But since bourgeois historians have adopted what is a particular form of vulgar materialism, Marxists had to remind them that history is the struggle of men for ideas, as well as a reflection of their material environment. Mr Trevor-Roper [a famous right-wing historian] is not merely mistaken in believing that the English Revolution was the reflection of the declining fortunes of country gentlemen, but also in his belief that Puritanism was simply a reflection of their impending bankruptcies.”

To Hobsbawm’s critique, it could be added that the so-called “rational choice theory” (so dominant in recent years in large parts of mainstream economics and political analysis) thrives on a single-minded focus on self-interest as the sole human motivation, thereby missing comprehensively the balance that Marx had argued for. A rational choice theorist can, in fact, learn a great deal from reading Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts and The German Ideology. While this would be a very different lesson from what Marx wanted Hegelians to consider, a commitment to doing justice to the two-way relations characterises both parts of Marx’s capacious pedagogy. What has to be avoided is the narrowing of Marx’s thoughts through simple formulas respectfully distributed in his name.

In remembering Marx on his 200th birthday, we not only celebrate a great intellectual, but also one whose critical analyses and investigations have many insights to offer to us today. Paying attention to Marx may be more important than paying him respect.

-------

Slavoj Zizek in The Independent

There is a delicious old Soviet joke about Radio Yerevan: a listener asks: “Is it true that Rabinovitch won a new car in the lottery?”, and the radio presenter answers: “In principle yes, it’s true, only it wasn’t a new car but an old bicycle, and he didn’t win it but it was stolen from him.”

Does exactly the same not hold for Marx’s legacy today? Let’s ask Radio Yerevan: “Is Marx’s theory still relevant today?” We can guess the answer: in principle yes, he describes wonderfully the mad dance of capitalist dynamics which only reached its peak today, more than a century and a half later, but… Gerald A Cohen enumerated the four features of the classic Marxist notion of the working class: (1) it constitutes the majority of society; (2) it produces the wealth of society; (3) it consists of the exploited members of society; and (4) its members are the needy people in society. When these four features are combined, they generate two further features: (5) the working class has nothing to lose from revolution; and (6) it can and will engage in a revolutionary transformation of society.

None of the first four features applies to today’s working class, which is why features (5) and (6) cannot be generated. Even if some of the features continue to apply to parts of today’s society, they are no longer united in a single agent: the needy people in society are no longer the workers, and so on.

But let’s dig into this question of relevance and appropriateness further. Not only is Marx’s critique of political economy and his outline of the capitalist dynamics still fully relevant, but one could even take a step further and claim that it is only today, with global capitalism, that it is fully relevant.

However, at the moment of triumph is one of defeat. After overcoming external obstacles the new threat comes from within. In other words, Marx was not simply wrong, he was often right – but more literally than he himself expected to be.

For example, Marx couldn’t have imagined that the capitalist dynamics of dissolving all particular identities would translate into ethnic identities as well. Today’s celebration of “minorities” and “marginals” is the predominant majority position – alt-rightists who complain about the terror of “political correctness” take advantage of this by presenting themselves as protectors of an endangered minority, attempting to mirror campaigns on the other side.

And then there’s the case of “commodity fetishism”. Recall the classic joke about a man who believes himself to be a grain of seed and is taken to a mental institution where the doctors do their best to finally convince him that he is not a grain but a man. When he is cured (convinced that he is not a grain of seed but a man) and allowed to leave the hospital, he immediately comes back trembling. There is a chicken outside the door and he is afraid that it will eat him.

“Dear fellow,” says his doctor, “you know very well that you are not a grain of seed but a man.”

“Of course I know that,” replies the patient, “but does the chicken know it?”

So how does this apply to the notion of commodity fetishism? Note the very beginning of the subchapter on commodity fetishism in Marx’s Das Kapital: “A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.”

Commodity fetishism (our belief that commodities are magic objects, endowed with an inherent metaphysical power) is not located in our mind, in the way we (mis)perceive reality, but in our social reality itself. We may know the truth, but we act as if we don’t know it – in our real life, we act like the chicken from the joke.

Niels Bohr, who already gave the right answer to Einstein’s “God doesn’t play dice“(“Don’t tell God what to do!”), also provided the perfect example of how a fetishist disavowal of belief works. Seeing a horseshoe on his door, a surprised visitor commented that he didn’t think Bohr believed superstitious ideas about horseshoes bringing good luck to people. Bohr snapped back: “I also do not believe in it; I have it there because I was told that it works whether one believes in it or not!”

This is how ideology works in our cynical era: we don’t have to believe in it. Nobody takes democracy or justice seriously, we are all aware of their corruption, but we practice them – in other words, we display our belief in them – because we assume they work even if we do not believe in them.

With regard to religion, we no longer “really believe”, we just follow (some of the) religious rituals and mores as part of the respect for the “lifestyle” of the community to which we belong (non-believing Jews obeying kosher rules “out of respect for tradition”, for example).

“I do not really believe in it, it is just part of my culture” seems to be the predominant mode of the displaced belief, characteristic of our times. “Culture” is the name for all those things we practice without really believing in them, without taking them quite seriously.

This is why we dismiss fundamentalist believers as “barbarians” or “primitive”, as anti-cultural, as a threat to culture – they dare to take seriously their beliefs. The cynical era in which we live would have no surprises for Marx.

Marx’s theories are thus not simply alive: Marx is a ghost who continues to haunt us – and the only way to keep him alive is to focus on those of his insights which are today more true than in his own time.

How should we think about Karl Marx on his 200th birthday? His big influence on the politics of the world is universally acknowledged, though people would differ on how good or bad that influence has been. But going beyond that, there can be little doubt that the intellectual world has been transformed by the reflective departures Marx generated, from class analysis as an essential part of social understanding, to the explication of the profound contrast between needs and hard work as conflicting foundations of people’s moral entitlements. Some of the influences have been so pervasive, with such strong impact on the concepts and connection we look for in our day-to-day analysis, that we may not be fully aware where the influences came from. In reading some classic works of Marx, we are often placed in the uncomfortable position of the theatre-goer who loved Hamlet as a play, but wondered why it was so full of quotations.

Marxian analysis remains important today not just because of Marx’s own original work, but also because of the extraordinary contributions made in that tradition by many leading historians, social scientists and creative artists — from Antonio Gramsci, Rosa Luxemburg, Jean-Paul Sartre and Bertolt Brecht to Piero Sraffa, Maurice Dobb and Eric Hobsbawm (to mention just a few names). We do not have to be a Marxist to make use of the richness of Marx’s insights — just as one does not have to be an Aristotelian to learn from Aristotle.

There are ideas in Marx’s corpus of work that remain under-explored. I would place among the relatively neglected ideas Marx’s highly original concept of “objective illusion,” and related to that, his discussion of “false consciousness”. An objective illusion may arise from what we can see from our particular position — how things look from there (no matter how misleading). Consider the relative sizes of the sun and the moon, and the fact that from the earth they look to be about the same size (Satyajit Ray offered some interesting conversations on this phenomenon in his film, Agantuk). But to conclude from this observation that the sun and the moon are in fact of the same size in terms of mass or volume would be mistaken, and yet to deny that they do look to be about the same size from the earth would be a mistake too. Marx’s investigation of objective illusion — of “the outer form of things” — is a pioneering contribution to understanding the implications of positional dependence of observations.

The phenomenon of objective illusion helps to explain the widespread tendency of workers in an exploitative society to fail to see that there is any exploitation going on — an example that Marx did much to investigate, in the form of “false consciousness”. The idea can have many applications going beyond Marx’s own use of it. Powerful use can be made of the notion of objective illusion to understand, for example, how women, and indeed men, in strongly sexist societies may not see clearly enough — in the absence of informed political agitation — that there are huge elements of gender inequality in what look like family-oriented just societies, as bastions of role-based fairness.

There is, however, a danger in seeing Marx in narrowly formulaic terms — for example, in seeing him as a “materialist” who allegedly understood the world in terms of the importance of material conditions, denying the significance of ideas and beliefs. This is not only a serious misreading of Marx, who emphasised two-way relations between ideas and material conditions, but also a seriously missed opportunity to see the far-reaching role of ideas on which Marx threw such important light.

Let me illustrate the point with a debate on the discipline of historical explanation that was quite widespread in our own time. In one of Eric Hobsbawm’s lesser known essays, called “Where Are British Historians Going?”, published in the Marxist Quarterly in 1955, he discussed how the Marxist pointer to the two-way relationship between ideas and material conditions offers very different lessons in the contemporary world than it had in the intellectual world that Marx himself saw around him, where the prevailing focus — for example by Hegel and Hegelians — was very much on highlighting the influence of ideas on material conditions.

In contrast, the tendency of dominant schools of history in the mid-twentieth century — Hobsbawm cited here the hugely influential historical works of Lewis Bernstein Namier — had come to embrace a type of materialism that saw human action as being almost entirely motivated by a simple kind of material interest, in particular narrowly defined self-interest. Given this completely different kind of bias (very far removed from the idealist traditions of Hegel and other influential thinkers in Marx’s own time), Hobsbawm argued that a balanced two-way view must demand that analysis in Marxian lines today must particularly emphasise the importance of ideas and their influence on material conditions.

For example, it is crucial to recognise that Edmund Burke’s hugely influential criticism of Warren Hastings’s misbehaviour in India — in the famous Impeachment hearings — was directly related to Burke’s strongly held ideas of justice and fairness, whereas the self-interest-obsessed materialist historians, such as Namier, saw no more in Burke’s discontent than the influence of his [Burke’s] profit-seeking concerns which had suffered because of the policies pursued by Hastings. The overreliance on materialism — in fact of a particularly narrow kind — needed serious correction, argued Hobsbawm: “In the pre-Namier days, Marxists regarded it as one of their chief historical duties to draw attention to the material basis of politics. But since bourgeois historians have adopted what is a particular form of vulgar materialism, Marxists had to remind them that history is the struggle of men for ideas, as well as a reflection of their material environment. Mr Trevor-Roper [a famous right-wing historian] is not merely mistaken in believing that the English Revolution was the reflection of the declining fortunes of country gentlemen, but also in his belief that Puritanism was simply a reflection of their impending bankruptcies.”

To Hobsbawm’s critique, it could be added that the so-called “rational choice theory” (so dominant in recent years in large parts of mainstream economics and political analysis) thrives on a single-minded focus on self-interest as the sole human motivation, thereby missing comprehensively the balance that Marx had argued for. A rational choice theorist can, in fact, learn a great deal from reading Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts and The German Ideology. While this would be a very different lesson from what Marx wanted Hegelians to consider, a commitment to doing justice to the two-way relations characterises both parts of Marx’s capacious pedagogy. What has to be avoided is the narrowing of Marx’s thoughts through simple formulas respectfully distributed in his name.

In remembering Marx on his 200th birthday, we not only celebrate a great intellectual, but also one whose critical analyses and investigations have many insights to offer to us today. Paying attention to Marx may be more important than paying him respect.

-------

Slavoj Zizek in The Independent

There is a delicious old Soviet joke about Radio Yerevan: a listener asks: “Is it true that Rabinovitch won a new car in the lottery?”, and the radio presenter answers: “In principle yes, it’s true, only it wasn’t a new car but an old bicycle, and he didn’t win it but it was stolen from him.”

Does exactly the same not hold for Marx’s legacy today? Let’s ask Radio Yerevan: “Is Marx’s theory still relevant today?” We can guess the answer: in principle yes, he describes wonderfully the mad dance of capitalist dynamics which only reached its peak today, more than a century and a half later, but… Gerald A Cohen enumerated the four features of the classic Marxist notion of the working class: (1) it constitutes the majority of society; (2) it produces the wealth of society; (3) it consists of the exploited members of society; and (4) its members are the needy people in society. When these four features are combined, they generate two further features: (5) the working class has nothing to lose from revolution; and (6) it can and will engage in a revolutionary transformation of society.

None of the first four features applies to today’s working class, which is why features (5) and (6) cannot be generated. Even if some of the features continue to apply to parts of today’s society, they are no longer united in a single agent: the needy people in society are no longer the workers, and so on.

But let’s dig into this question of relevance and appropriateness further. Not only is Marx’s critique of political economy and his outline of the capitalist dynamics still fully relevant, but one could even take a step further and claim that it is only today, with global capitalism, that it is fully relevant.

However, at the moment of triumph is one of defeat. After overcoming external obstacles the new threat comes from within. In other words, Marx was not simply wrong, he was often right – but more literally than he himself expected to be.

For example, Marx couldn’t have imagined that the capitalist dynamics of dissolving all particular identities would translate into ethnic identities as well. Today’s celebration of “minorities” and “marginals” is the predominant majority position – alt-rightists who complain about the terror of “political correctness” take advantage of this by presenting themselves as protectors of an endangered minority, attempting to mirror campaigns on the other side.

And then there’s the case of “commodity fetishism”. Recall the classic joke about a man who believes himself to be a grain of seed and is taken to a mental institution where the doctors do their best to finally convince him that he is not a grain but a man. When he is cured (convinced that he is not a grain of seed but a man) and allowed to leave the hospital, he immediately comes back trembling. There is a chicken outside the door and he is afraid that it will eat him.

“Dear fellow,” says his doctor, “you know very well that you are not a grain of seed but a man.”

“Of course I know that,” replies the patient, “but does the chicken know it?”

So how does this apply to the notion of commodity fetishism? Note the very beginning of the subchapter on commodity fetishism in Marx’s Das Kapital: “A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.”

Commodity fetishism (our belief that commodities are magic objects, endowed with an inherent metaphysical power) is not located in our mind, in the way we (mis)perceive reality, but in our social reality itself. We may know the truth, but we act as if we don’t know it – in our real life, we act like the chicken from the joke.

Niels Bohr, who already gave the right answer to Einstein’s “God doesn’t play dice“(“Don’t tell God what to do!”), also provided the perfect example of how a fetishist disavowal of belief works. Seeing a horseshoe on his door, a surprised visitor commented that he didn’t think Bohr believed superstitious ideas about horseshoes bringing good luck to people. Bohr snapped back: “I also do not believe in it; I have it there because I was told that it works whether one believes in it or not!”

This is how ideology works in our cynical era: we don’t have to believe in it. Nobody takes democracy or justice seriously, we are all aware of their corruption, but we practice them – in other words, we display our belief in them – because we assume they work even if we do not believe in them.

With regard to religion, we no longer “really believe”, we just follow (some of the) religious rituals and mores as part of the respect for the “lifestyle” of the community to which we belong (non-believing Jews obeying kosher rules “out of respect for tradition”, for example).

“I do not really believe in it, it is just part of my culture” seems to be the predominant mode of the displaced belief, characteristic of our times. “Culture” is the name for all those things we practice without really believing in them, without taking them quite seriously.

This is why we dismiss fundamentalist believers as “barbarians” or “primitive”, as anti-cultural, as a threat to culture – they dare to take seriously their beliefs. The cynical era in which we live would have no surprises for Marx.

Marx’s theories are thus not simply alive: Marx is a ghost who continues to haunt us – and the only way to keep him alive is to focus on those of his insights which are today more true than in his own time.

Sunday, 22 April 2018

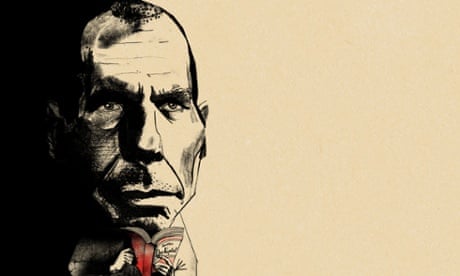

Marx predicted our present crisis – and points the way out

Yanis Varoufakis in The Guardian

For a manifesto to succeed, it must speak to our hearts like a poem while infecting the mind with images and ideas that are dazzlingly new. It needs to open our eyes to the true causes of the bewildering, disturbing, exciting changes occurring around us, exposing the possibilities with which our current reality is pregnant. It should make us feel hopelessly inadequate for not having recognised these truths ourselves, and it must lift the curtain on the unsettling realisation that we have been acting as petty accomplices, reproducing a dead-end past. Lastly, it needs to have the power of a Beethoven symphony, urging us to become agents of a future that ends unnecessary mass suffering and to inspire humanity to realise its potential for authentic freedom.

No manifesto has better succeeded in doing all this than the one published in February 1848 at 46 Liverpool Street, London. Commissioned by English revolutionaries, The Communist Manifesto (or the Manifesto of the Communist Party, as it was first published) was authored by two young Germans – Karl Marx, a 29-year-old philosopher with a taste for epicurean hedonism and Hegelian rationality, and Friedrich Engels, a 28-year-old heir to a Manchester mill.

As a work of political literature, the manifesto remains unsurpassed. Its most infamous lines, including the opening one (“A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of communism”), have a Shakespearean quality. Like Hamlet confronted by the ghost of his slain father, the reader is compelled to wonder: “Should I conform to the prevailing order, suffering the slings and arrows of the outrageous fortune bestowed upon me by history’s irresistible forces? Or should I join these forces, taking up arms against the status quo and, by opposing it, usher in a brave new world?”

For Marx and Engels’ immediate readership, this was not an academic dilemma, debated in the salons of Europe. Their manifesto was a call to action, and heeding this spectre’s invocation often meant persecution, or, in some cases, lengthy imprisonment. Today, a similar dilemma faces young people: conform to an established order that is crumbling and incapable of reproducing itself, or oppose it, at considerable personal cost, in search of new ways of working, playing and living together? Even though communist parties have disappeared almost entirely from the political scene, the spirit of communism driving the manifesto is proving hard to silence.

To see beyond the horizon is any manifesto’s ambition. But to succeed as Marx and Engels did in accurately describing an era that would arrive a century-and-a-half in the future, as well as to analyse the contradictions and choices we face today, is truly astounding. In the late 1840s, capitalism was foundering, local, fragmented and timid. And yet Marx and Engels took one long look at it and foresaw our globalised, financialised, iron-clad, all-singing-all-dancing capitalism. This was the creature that came into being after 1991, at the very same moment the establishment was proclaiming the death of Marxism and the end of history.

Of course, the predictive failure of The Communist Manifesto has long been exaggerated. I remember how even leftwing economists in the early 1970s challenged the pivotal manifesto prediction that capital would “nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere”. Drawing upon the sad reality of what were then called third world countries, they argued that capital had lost its fizz well before expanding beyond its “metropolis” in Europe, America and Japan.

Empirically they were correct: European, US and Japanese multinational corporations operating in the “peripheries” of Africa, Asia and Latin America were confining themselves to the role of colonial resource extractors and failing to spread capitalism there. Instead of imbuing these countries with capitalist development (drawing “all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilisation”), they argued that foreign capital was reproducing the development of underdevelopment in the third world. It was as if the manifesto had placed too much faith in capital’s ability to spread into every nook and cranny. Most economists, including those sympathetic to Marx, doubted the manifesto’s prediction that “exploitation of the world-market” would give “a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country”.

As it turned out, the manifesto was right, albeit belatedly. It would take the collapse of the Soviet Union and the insertion of two billion Chinese and Indian workers into the capitalist labour market for its prediction to be vindicated. Indeed, for capital to globalise fully, the regimes that pledged allegiance to the manifesto had first to be torn asunder. Has history ever procured a more delicious irony?

Anyone reading the manifesto today will be surprised to discover a picture of a world much like our own, teetering fearfully on the edge of technological innovation. In the manifesto’s time, it was the steam engine that posed the greatest challenge to the rhythms and routines of feudal life. The peasantry were swept into the cogs and wheels of this machinery and a new class of masters, the factory owners and the merchants, usurped the landed gentry’s control over society. Now, it is artificial intelligence and automation that loom as disruptive threats, promising to sweep away “all fixed, fast-frozen relations”. “Constantly revolutionising … instruments of production,” the manifesto proclaims, transform “the whole relations of society”, bringing about “constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation”.

For a manifesto to succeed, it must speak to our hearts like a poem while infecting the mind with images and ideas that are dazzlingly new. It needs to open our eyes to the true causes of the bewildering, disturbing, exciting changes occurring around us, exposing the possibilities with which our current reality is pregnant. It should make us feel hopelessly inadequate for not having recognised these truths ourselves, and it must lift the curtain on the unsettling realisation that we have been acting as petty accomplices, reproducing a dead-end past. Lastly, it needs to have the power of a Beethoven symphony, urging us to become agents of a future that ends unnecessary mass suffering and to inspire humanity to realise its potential for authentic freedom.

No manifesto has better succeeded in doing all this than the one published in February 1848 at 46 Liverpool Street, London. Commissioned by English revolutionaries, The Communist Manifesto (or the Manifesto of the Communist Party, as it was first published) was authored by two young Germans – Karl Marx, a 29-year-old philosopher with a taste for epicurean hedonism and Hegelian rationality, and Friedrich Engels, a 28-year-old heir to a Manchester mill.

As a work of political literature, the manifesto remains unsurpassed. Its most infamous lines, including the opening one (“A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of communism”), have a Shakespearean quality. Like Hamlet confronted by the ghost of his slain father, the reader is compelled to wonder: “Should I conform to the prevailing order, suffering the slings and arrows of the outrageous fortune bestowed upon me by history’s irresistible forces? Or should I join these forces, taking up arms against the status quo and, by opposing it, usher in a brave new world?”

For Marx and Engels’ immediate readership, this was not an academic dilemma, debated in the salons of Europe. Their manifesto was a call to action, and heeding this spectre’s invocation often meant persecution, or, in some cases, lengthy imprisonment. Today, a similar dilemma faces young people: conform to an established order that is crumbling and incapable of reproducing itself, or oppose it, at considerable personal cost, in search of new ways of working, playing and living together? Even though communist parties have disappeared almost entirely from the political scene, the spirit of communism driving the manifesto is proving hard to silence.

To see beyond the horizon is any manifesto’s ambition. But to succeed as Marx and Engels did in accurately describing an era that would arrive a century-and-a-half in the future, as well as to analyse the contradictions and choices we face today, is truly astounding. In the late 1840s, capitalism was foundering, local, fragmented and timid. And yet Marx and Engels took one long look at it and foresaw our globalised, financialised, iron-clad, all-singing-all-dancing capitalism. This was the creature that came into being after 1991, at the very same moment the establishment was proclaiming the death of Marxism and the end of history.

Of course, the predictive failure of The Communist Manifesto has long been exaggerated. I remember how even leftwing economists in the early 1970s challenged the pivotal manifesto prediction that capital would “nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere”. Drawing upon the sad reality of what were then called third world countries, they argued that capital had lost its fizz well before expanding beyond its “metropolis” in Europe, America and Japan.

Empirically they were correct: European, US and Japanese multinational corporations operating in the “peripheries” of Africa, Asia and Latin America were confining themselves to the role of colonial resource extractors and failing to spread capitalism there. Instead of imbuing these countries with capitalist development (drawing “all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilisation”), they argued that foreign capital was reproducing the development of underdevelopment in the third world. It was as if the manifesto had placed too much faith in capital’s ability to spread into every nook and cranny. Most economists, including those sympathetic to Marx, doubted the manifesto’s prediction that “exploitation of the world-market” would give “a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country”.

As it turned out, the manifesto was right, albeit belatedly. It would take the collapse of the Soviet Union and the insertion of two billion Chinese and Indian workers into the capitalist labour market for its prediction to be vindicated. Indeed, for capital to globalise fully, the regimes that pledged allegiance to the manifesto had first to be torn asunder. Has history ever procured a more delicious irony?

Anyone reading the manifesto today will be surprised to discover a picture of a world much like our own, teetering fearfully on the edge of technological innovation. In the manifesto’s time, it was the steam engine that posed the greatest challenge to the rhythms and routines of feudal life. The peasantry were swept into the cogs and wheels of this machinery and a new class of masters, the factory owners and the merchants, usurped the landed gentry’s control over society. Now, it is artificial intelligence and automation that loom as disruptive threats, promising to sweep away “all fixed, fast-frozen relations”. “Constantly revolutionising … instruments of production,” the manifesto proclaims, transform “the whole relations of society”, bringing about “constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation”.

Composite: Guardian Design

For Marx and Engels, however, this disruption is to be celebrated. It acts as a catalyst for the final push humanity needs to do away with our remaining prejudices that underpin the great divide between those who own the machines and those who design, operate and work with them. “All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned,” they write in the manifesto of technology’s effect, “and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind”. By ruthlessly vaporising our preconceptions and false certainties, technological change is forcing us, kicking and screaming, to face up to how pathetic our relations with one another are.

Today, we see this reckoning in millions of words, in print and online, used to debate globalisation’s discontents. While celebrating how globalisation has shifted billions from abject poverty to relative poverty, venerable western newspapers, Hollywood personalities, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, bishops and even multibillionaire financiers all lament some of its less desirable ramifications: unbearable inequality, brazen greed, climate change, and the hijacking of our parliamentary democracies by bankers and the ultra-rich.

None of this should surprise a reader of the manifesto. “Society as a whole,” it argues, “is more and more splitting up into two great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other.” As production is mechanised, and the profit margin of the machine-owners becomes our civilisation’s driving motive, society splits between non-working shareholders and non-owner wage-workers. As for the middle class, it is the dinosaur in the room, set for extinction.

At the same time, the ultra-rich become guilt-ridden and stressed as they watch everyone else’s lives sink into the precariousness of insecure wage-slavery. Marx and Engels foresaw that this supremely powerful minority would eventually prove “unfit to rule” over such polarised societies, because they would not be in a position to guarantee the wage-slaves a reliable existence. Barricaded in their gated communities, they find themselves consumed by anxiety and incapable of enjoying their riches. Some of them, those smart enough to realise their true long-term self-interest, recognise the welfare state as the best available insurance policy. But alas, explains the manifesto, as a social class, it will be in their nature to skimp on the insurance premium, and they will work tirelessly to avoid paying the requisite taxes.

Is this not what has transpired? The ultra-rich are an insecure, permanently disgruntled clique, constantly in and out of detox clinics, relentlessly seeking solace from psychics, shrinks and entrepreneurial gurus. Meanwhile, everyone else struggles to put food on the table, pay tuition fees, juggle one credit card for another or fight depression. We act as if our lives are carefree, claiming to like what we do and do what we like. Yet in reality, we cry ourselves to sleep.

Do-gooders, establishment politicians and recovering academic economists all respond to this predicament in the same way, issuing fiery condemnations of the symptoms (income inequality) while ignoring the causes (exploitation resulting from the unequal property rights over machines, land, resources). Is it any wonder we are at an impasse, wallowing in hopelessness that only serves the populists seeking to court the worst instincts of the masses?

With the rapid rise of advanced technology, we are brought closer to the moment when we must decide how to relate to each other in a rational, civilised manner. We can no longer hide behind the inevitability of work and the oppressive social norms it necessitates. The manifesto gives its 21st-century reader an opportunity to see through this mess and to recognise what needs to be done so that the majority can escape from discontent into new social arrangements in which “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all”. Even though it contains no roadmap of how to get there, the manifesto remains a source of hope not to be dismissed.

If the manifesto holds the same power to excite, enthuse and shame us that it did in 1848, it is because the struggle between social classes is as old as time itself. Marx and Engels summed this up in 13 audacious words: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

From feudal aristocracies to industrialised empires, the engine of history has always been the conflict between constantly revolutionising technologies and prevailing class conventions. With each disruption of society’s technology, the conflict between us changes form. Old classes die out and eventually only two remain standing: the class that owns everything and the class that owns nothing – the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

This is the predicament in which we find ourselves today. While we owe capitalism for having reduced all class distinctions to the gulf between owners and non-owners, Marx and Engels want us to realise that capitalism is insufficiently evolved to survive the technologies it spawns. It is our duty to tear away at the old notion of privately owned means of production and force a metamorphosis, which must involve the social ownership of machinery, land and resources. Now, when new technologies are unleashed in societies bound by the primitive labour contract, wholesale misery follows. In the manifesto’s unforgettable words: “A society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells.”

The sorcerer will always imagine that their apps, search engines, robots and genetically engineered seeds will bring wealth and happiness to all. But, once released into societies divided between wage labourers and owners, these technological marvels will push wages and prices to levels that create low profits for most businesses. It is only big tech, big pharma and the few corporations that command exceptionally large political and economic power over us that truly benefit. If we continue to subscribe to labour contracts between employer and employee, then private property rights will govern and drive capital to inhuman ends. Only by abolishing private ownership of the instruments of mass production and replacing it with a new type of common ownership that works in sync with new technologies, will we lessen inequality and find collective happiness.

According to Marx and Engels’ 13-word theory of history, the current stand-off between worker and owner has always been guaranteed. “Equally inevitable,” the manifesto states, is the bourgeoisie’s “fall and the victory of the proletariat”. So far, history has not fulfilled this prediction, but critics forget that the manifesto, like any worthy piece of propaganda, presents hope in the form of certainty. Just as Lord Nelson rallied his troops before the Battle of Trafalgar by announcing that England “expected” them to do their duty (even if he had grave doubts that they would), the manifesto bestows upon the proletariat the expectation that they will do their duty to themselves, inspiring them to unite and liberate one another from the bonds of wage-slavery.

Will they? On current form, it seems unlikely. But, then again, we had to wait for globalisation to appear in the 1990s before the manifesto’s estimation of capital’s potential could be fully vindicated. Might it not be that the new global, increasingly precarious proletariat needs more time before it can play the historic role the manifesto anticipated? While the jury is still out, Marx and Engels tell us that, if we fear the rhetoric of revolution, or try to distract ourselves from our duty to one another, we will find ourselves caught in a vertiginous spiral in which capital saturates and bleaches the human spirit. The only thing we can be certain of, according to the manifesto, is that unless capital is socialised we are in for dystopic developments.

On the topic of dystopia, the sceptical reader will perk up: what of the manifesto’s own complicity in legitimising authoritarian regimes and steeling the spirit of gulag guards? Instead of responding defensively, pointing out that no one blames Adam Smith for the excesses of Wall Street, or the New Testament for the Spanish Inquisition, we can speculate how the authors of the manifesto might have answered this charge. I believe that, with the benefit of hindsight, Marx and Engels would confess to an important error in their analysis: insufficient reflexivity. This is to say that they failed to give sufficient thought, and kept a judicious silence, over the impact their own analysis would have on the world they were analysing.

The manifesto told a powerful story in uncompromising language, intended to stir readers from their apathy. What Marx and Engels failed to foresee was that powerful, prescriptive texts have a tendency to procure disciples, believers – a priesthood, even – and that this faithful might use the power bestowed upon them by the manifesto to their own advantage. With it, they might abuse other comrades, build their own power base, gain positions of influence, bed impressionable students, take control of the politburo and imprison anyone who resists them.

Similarly, Marx and Engels failed to estimate the impact of their writing on capitalism itself. To the extent that the manifesto helped fashion the Soviet Union, its eastern European satellites, Castro’s Cuba, Tito’s Yugoslavia and several social democratic governments in the west, would these developments not cause a chain reaction that would frustrate the manifesto’s predictions and analysis? After the Russian revolution and then the second world war, the fear of communism forced capitalist regimes to embrace pension schemes, national health services, even the idea of making the rich pay for poor and petit bourgeois students to attend purpose-built liberal universities. Meanwhile, rabid hostility to the Soviet Union stirred up paranoia and created a climate of fear that proved particularly fertile for figures such as Joseph Stalin and Pol Pot.

I believe that Marx and Engels would have regretted not anticipating the manifesto’s impact on the communist parties it foreshadowed. They would be kicking themselves that they overlooked the kind of dialectic they loved to analyse: how workers’ states would become increasingly totalitarian in their response to capitalist state aggression, and how, in their response to the fear of communism, these capitalist states would grow increasingly civilised.

Blessed, of course, are the authors whose errors result from the power of their words. Even more blessed are those whose errors are self-correcting. In our present day, the workers’ states inspired by the manifesto are almost gone, and the communist parties disbanded or in disarray. Liberated from competition with regimes inspired by the manifesto, globalised capitalism is behaving as if it is determined to create a world best explained by the manifesto.

What makes the manifesto truly inspiring today is its recommendation for us in the here and now, in a world where our lives are being constantly shaped by what Marx described in his earlier Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts as “a universal energy which breaks every limit and every bond and posits itself as the only policy, the only universality, the only limit and the only bond”. From Uber drivers and finance ministers to banking executives and the wretchedly poor, we can all be excused for feeling overwhelmed by this “energy”. Capitalism’s reach is so pervasive it can sometimes seem impossible to imagine a world without it. It is only a small step from feelings of impotence to falling victim to the assertion there is no alternative. But, astonishingly (claims the manifesto), it is precisely when we are about to succumb to this idea that alternatives abound.

What we don’t need at this juncture are sermons on the injustice of it all, denunciations of rising inequality or vigils for our vanishing democratic sovereignty. Nor should we stomach desperate acts of regressive escapism: the cry to return to some pre-modern, pre-technological state where we can cling to the bosom of nationalism. What the manifesto promotes in moments of doubt and submission is a clear-headed, objective assessment of capitalism and its ills, seen through the cold, hard light of rationality.

For Marx and Engels, however, this disruption is to be celebrated. It acts as a catalyst for the final push humanity needs to do away with our remaining prejudices that underpin the great divide between those who own the machines and those who design, operate and work with them. “All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned,” they write in the manifesto of technology’s effect, “and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind”. By ruthlessly vaporising our preconceptions and false certainties, technological change is forcing us, kicking and screaming, to face up to how pathetic our relations with one another are.

Today, we see this reckoning in millions of words, in print and online, used to debate globalisation’s discontents. While celebrating how globalisation has shifted billions from abject poverty to relative poverty, venerable western newspapers, Hollywood personalities, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, bishops and even multibillionaire financiers all lament some of its less desirable ramifications: unbearable inequality, brazen greed, climate change, and the hijacking of our parliamentary democracies by bankers and the ultra-rich.